“It is better to die for an idea that will live, than to live for an idea that will die.”

“The most potent weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed. So as a prelude whites must be made to realise that they are only human, not superior. Same with Blacks. They must be made to realise that they are also human, not inferior.”

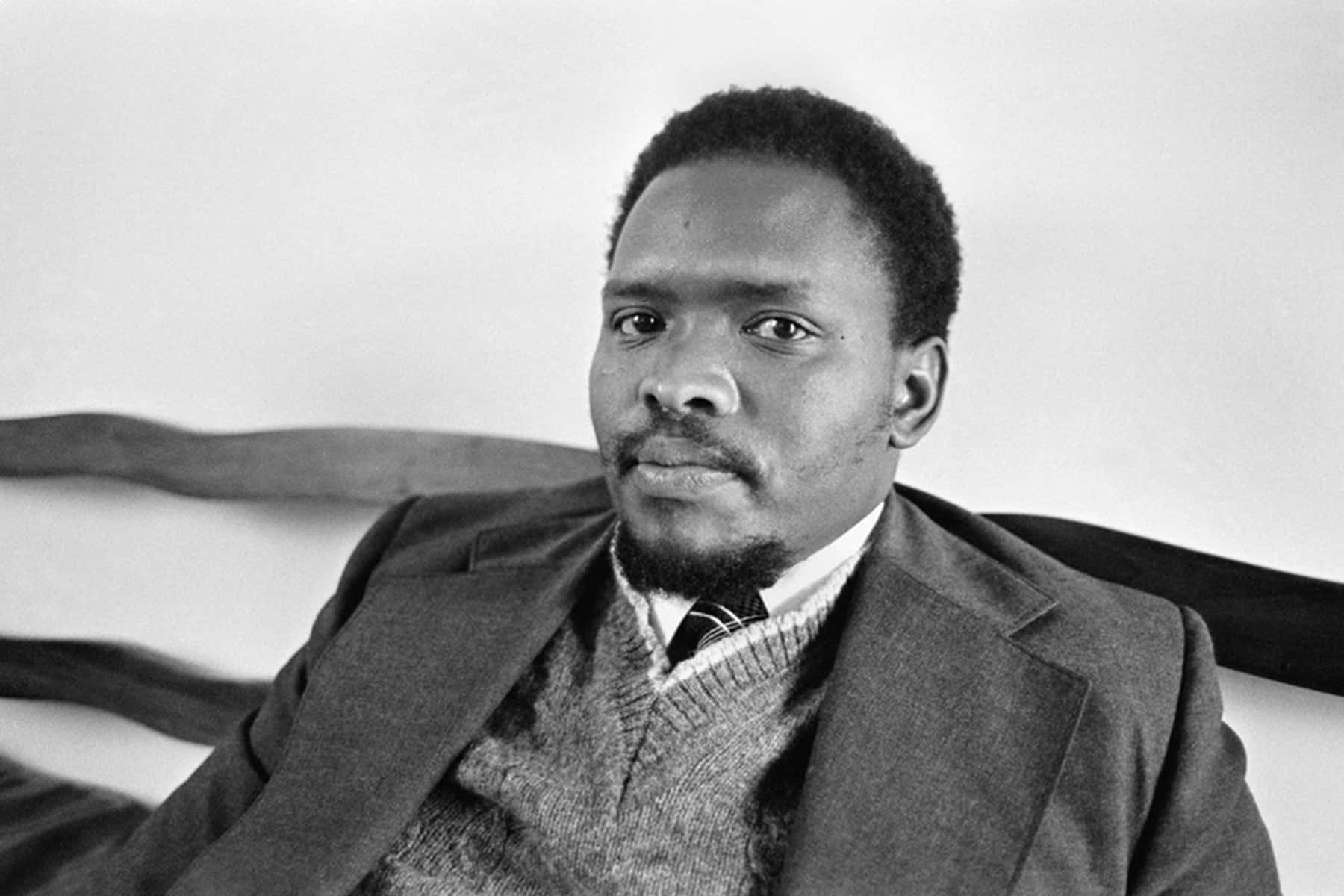

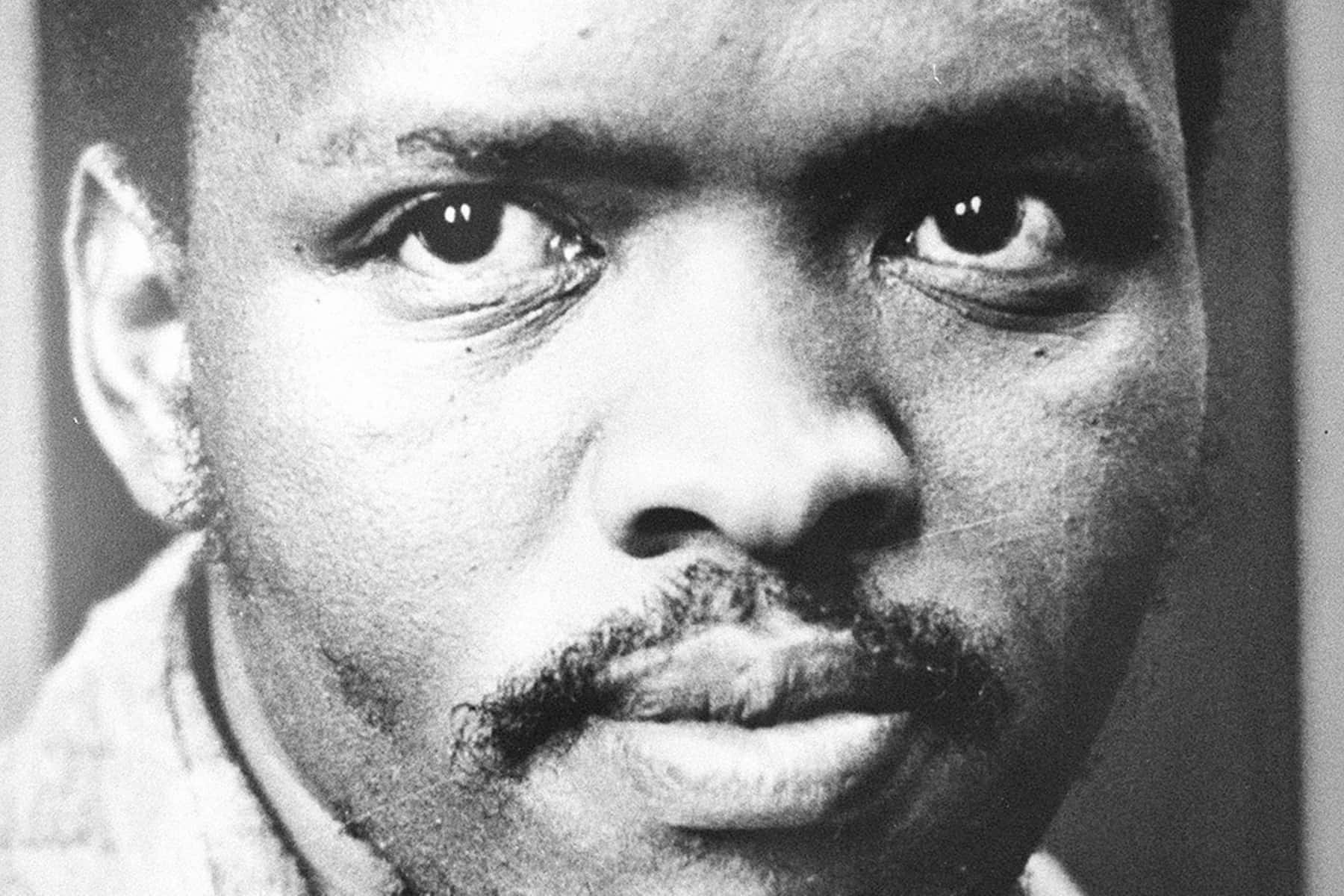

Both of the aforementioned quotes are from South African freedom fighter Steve Biko. Since I first learned of this great man back in the 1990s I have been an admirer of his work and philosophy. This man’s memory has been overshadowed by Nelson Mandela.

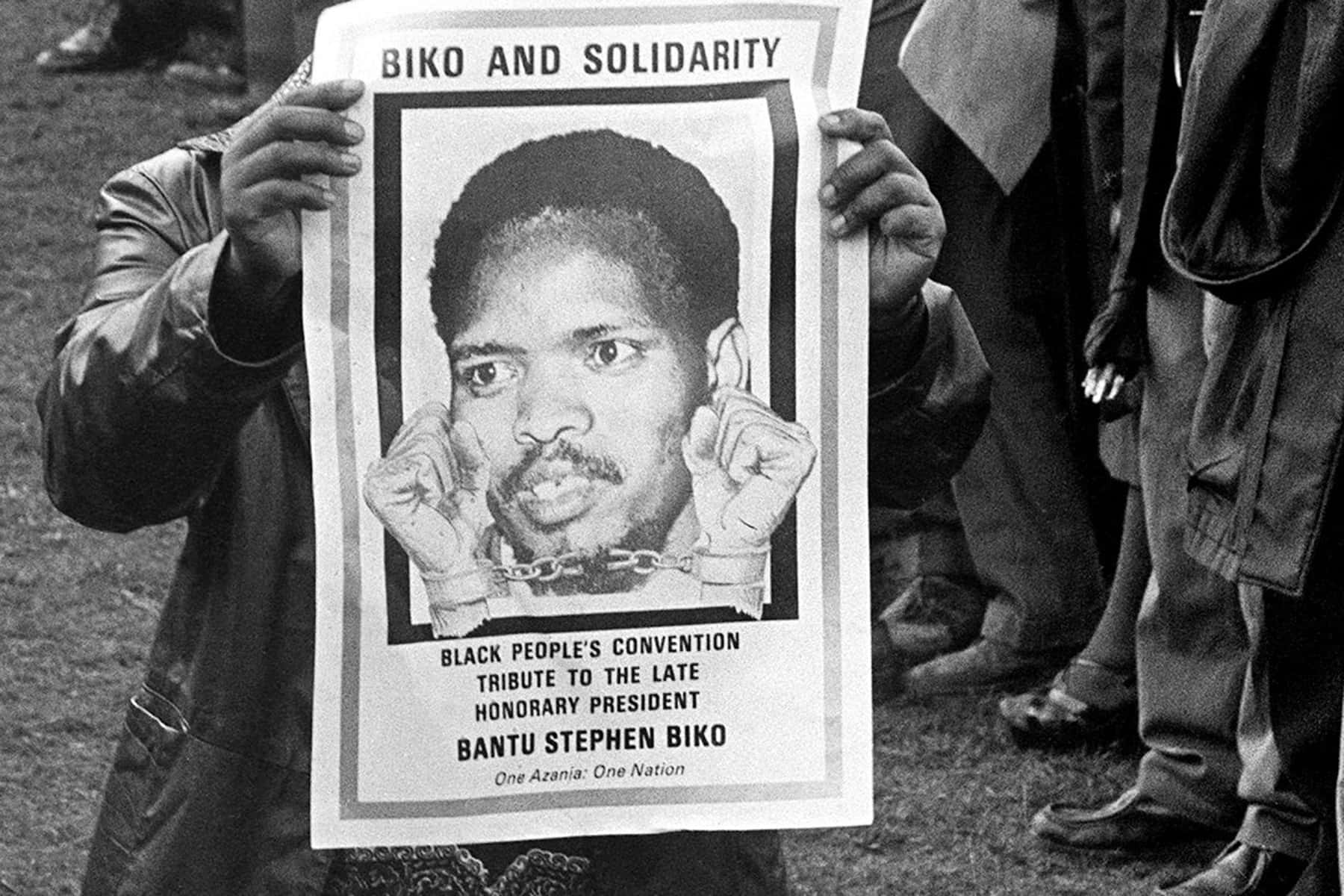

Steve Biko was an anti-apartheid activist. He co-founded the South African Students’ Organization, and the Black People’s Convention in 1972. Biko was arrested by South African police multiple times before they finally murdered him on September 12, 1977. He was banned by the government for his anti-apartheid work. Banning in South Africa is described by Brittanica as “an administrative action by which publications, organizations, or assemblies could be outlawed and suppressed and individual persons could be placed under severe restrictions of their freedom of travel, association, and speech.”

Despite his banning, he clandestinely continued his work. He spoke prior to his banning across the nation. In this 1971 speech he spoke about the need for Blacks to break the shackles of being told by White people how to advocate for change.

“[I]n South Africa political power has always rested with white society. Not only have the whites been guilty of being on the offensive but, by some skillful manoeuvres, they have managed to control the responses of the blacks to the provocation. Not only have they kicked the black but they have also told him how to react to the kick… [H]e is now beginning to show signs that it is his right and duty to respond to the kick in the way he sees fit …”

The first time I read his writings in a book called I Write What I Like, I became an instant fan of Biko. I was so proud of his insistence that no one could tell him what to write. The Apartheid government tried so hard to silence him that they eventually had to kill him to do so. He wrote a letter to his family apologizing for putting his work before them.

“I’ve devoted my life to see equality for blacks, and at the same time, I’ve denied the needs of my family. Please understand that I take these actions, not out of selfishness or arrogance, but to preserve a South Africa worth living in for blacks and whites.”

The dedication and passion for freedom that Biko displayed in his writings continues to inspire and guide me to this day. Speaking truth to power is often overrated. For Biko it was everything. Not allowing the oppressively racist Apartheid state to control the minds of Black people was the mission of the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa.

Biko was a huge critic of White liberals in South Africa. He spoke out about them doing what they did because of guilt and without a sense of real affection for Black people.

“A game at which the liberals have become masters is that of deliberate evasiveness. The question often comes up `what can you do?`. If you ask him to do something like stopping to use segregated facilities or dropping out of varsity to work at menial jobs like all blacks or defying and denouncing all provisions that make him privileged, you always get the answer – `but that’s unrealistic!’ While this may be true, it only serves to illustrate the fact that no matter what a white man does, the colour of his skin – his passport to privilege- will always put him miles ahead of the black men. Thus in the ultimate analysis, no white person can escape being part of the oppressor camp.”

This reminds me of the criticism of the White moderate that Dr. King spoke of in his famous Letter From a Birmingham Jail.

“First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.”

Black people like King and Biko have realized that there can be a duality in Whites who profess to be allies. On the one hand they denounce wrong doing, but on the other hand they sit back and continue to watch it play out.

One of the manifestations of this duality is when protests lead to violence or looting. Dr. King told us that “a riot is the language of the unheard.” As the protests in the wake of the murder of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd have played out across the country recent polls suggest that Whites are losing their patience and acceptance of the protests. Part of this is because the “loss of property” has become more important than the loss of human lives. Property can always be repaired and replaced, but lives can’t.

I use my platforms to speak about important, difficult issues related to racism in America. Most of my audiences around the state have been filled with white people. I have been told I have a unique ability to tell White people the truth without them getting mad at me. I don’t have any magic formula.

I was recently asked how my message changes from speaking to Blacks in Milwaukee to speaking among Whites in small town Wisconsin. It does not. I don’t have to change what I say because I use American history as my tool to provide context and understanding of how we got here.

The experiences of people of color in this country are littered with horrific violence, constant racism and discrimination, marginalization, exclusion and negativity from the primarily White society. This is not some big secret. We all know these things. Some White people deny them but they know the truth because they are a part of the truth. When racism occurs within our institutions White people are witnesses, or I should say silent witnesses. I had a friend years ago named Kelly Wright who used to say “never assume they don’t know.”

I have endeavored to learn American history in a very odd way. I look at the histories of all Americans. I have studied the history of enslaved Africans, White indentured servants, American elites, immigrants from Asia, Africa, Europe, Latin America, and the Indigenous people of this land. The diversity of lived experiences has taught me to see history as parallel journeys in time.

To study the history of people of color is to study the history of White people in this country. It is impossible to study the history of Native Americans since the fifteenth century without learning about White people. No study of the lives of African and African ancestored people is devoid of White people. The study of immigration to America by Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, Koreans, Hmong, Vietnamese and others from Asia requires you to see the role of Whites in those experiences. I have learned more about White people by studying the history of people of color than I could have ever hoped for.

We can see what these parallel journeys look like if we study time periods in history and explore what was going on in all of the different communities present at that time. A study of the American Revolution must include Europeans, Africans and Native Americans to be complete.

As I write and deliver lectures and workshops to people I use the little voice inside my head as a guide. It tells me I must be: honest, factual, and courageous. It tells me to provide historical context so that people can have productive conversations about race. Productive conversations are when you know enough about the true American history to talk. You are no longer speaking with a lack of understanding. You know the root causes of America’s racial problems.

When you have productive conversations you don’t run from the reality that racism is embedded in the psyche of America. You don’t feel a need to guilt White people. You simply acknowledge the truth and live with it. You understand that White people are born into a system of privilege whether they ask for it or not. You understand that White people know it’s better to be white than non-white. You are clear that this system is not going to be dismantled without Herculean efforts.

I will continue to use my voice as a weapon. Weapons are designed to protect and to destroy our enemies. They can be used for defensive purposes and offensive purposes. Mine are used to defend the honor and integrity of communities of people of color and to battle against those who want to do them harm.

“I’m going to be me as I am, and you can beat me or jail me or even kill me, but I’m not going to be what you want me to be.” – Steve Biko