Milwaukee’s current struggles to stem the growth of COVID-19 Coronavirus eerily parallels efforts to combat another pandemic over a century ago. In 1918, the Spanish Flu killed more than 50 million people — some estimate nearly 100 million — worldwide.

It was the worst public health disaster in American history, but its place in our collective memory has been overshadowed by World War I, with its senseless carnage, crusading energy, despicable villains and brave heroes. No one who lived then could have imagined a crisis of such epic scale could be repeated, but one of history’s hard lessons is that they can and are repeated. [1]

The Spanish Flu first appeared in eastern Kаnsаs, infecting soldiers at Camp Funston in March 1918. This first wave was rather mild and, thus, went largely unnoticed by the general public. The infected men survived but carried the virus to other Army camps and overseas, where it quickly spread among British, French and German troops. It is believed the virus mutated into a more virulent strain that ravaged Europe and spread along international trade routes and naval supply lines, finally returning to the United States in late summer. The ferocity of the disease caught medical professionals off guard. Similar to COVID-19, Spanish Flu symptoms — chills followed by high fever, body aches and runny eyes — mirrored those of the “grippe” or common winter flu but incapacitated victims without warning. Twenty per cent of those infected developed pneumonia, and nearly half of those cases developed heliotrope cyanosis, filling the victim’s lungs with a thick, blackish liquid that turned their skin black-blue. Those cases were usually fatal within 48 hours. In addition, the Spanish Flu was highly contagious and could be spread rapidly through contact with the sick or through sneezing or coughing by an infected person. The virus could linger airborne for hours if not exposed to sunlight; one individual could infect an entire enclosed building. [2]

Dr. B. F. Koch at the Emergency Hospital on Michigan Street diagnosed Milwaukee’s first Spanish Flu cases on Sunday, September 15, 1918. One patient was a laborer from a Great Lakes freighter, and the other was a sailor on leave from the Great Lakes Naval Training Station across the border in Illinois. [3] The station was the largest naval training facility in the world, with some 45,000 men. The disease first struck there on September 11 and quickly overwhelmed its medical facilities. One week later, the camp hospital — with only 42 beds — treated 2,600 men. Sick men had to lie on stretchers on the floor, waiting for those on cots to die. One nurse remembered bodies “stacked in the morgue from floor to ceiling like cord wood.” Despite the devastation, furloughs were still granted, and the men spread the disease to Chicago and Milwaukee.

Immediately after Milwaukee’s first cases were reported, Health Commissioner George Ruhland contacted the station’s commandant, who agreed to suspend leaves and place the camp under quarantine until the flu subsided. But the genie was out of the bottle. On September 21, the Milwaukee Leader reported the number of sick in Milwaukee had increased to 100, including one girl who contracted the flu from her brother on leave from the Great Lakes Station. Other newspapers indicated the total was probably higher because doctors were not compelled by law to report influenza or pneumonia cases. On September 23, Private K.C. Adams of the Marine Corps became the city’s first flu-related death. Ruhland reassured city residents there was no need to worry but encouraged everyone to avoid crowds and refrain from kissing and shaking hands. Above all, he told newspaper reporters, “the public must not allow itself to become stampeded…No one should be scared by the term ‘Spanish’ influenza’ for it is the same old influenza.” [4]

It seemed as if most Milwaukeeans were unconcerned about the microscopic menace. They went about daily routines, focused on exciting news from the war front as Allied forces pushed the Germans back, and occupied themselves with the government’s fourth Liberty Loan Drive. On September 27, a large gathering of loan workers met at the Strand Theater; the following day, the city staged a massive parade — disregarding Ruhland’s warning about crowds — to kick off the drive. Roughly 25,000 participants and thousands of spectators crammed along city streets, providing the ideal setting for spreading deadly germs.

Some Milwaukee residents, however, were understandably jittery. On September 23, Anita Weschler wrote her husband about Juanita Johnson, who died after developing pneumonia: “It is very sad I think, especially so as she leaves so many small children.” Two days later, she watched the funeral procession and noted that Juanita’s husband looked as though he had been crying quite a bit. “I have never seen a man who had lost his wife,” she wrote, “and can’t imagine how most of them act, and feel.” A week later, Anita complained about a cold and that her son was sick with a fever and prayed “that we do not come down with this Influenza, as everybody seems to be having it. There are three right next door at Cottrills sick with it now.” [5]

Anita and her son recovered, but the epidemic ripped through the city in early October. The number of cases reported daily exploded from 69 on October 5 to 214 on October 7 to 340 on October 8 and to 453 on October 11. The total number of cases as of the 11th reached 2,097 while the number of deaths counted 50. An alarmed Common Council met on October 9 and granted Ruhland power to take any steps necessary to check the flu’s spread. He warned the Council that Milwaukee could expect 40 percent of its population, or 180,000 people, to be affected, resulting in about 2,000 deaths. “We must do all in our power,” he insisted, “to prevent such a calamity.”

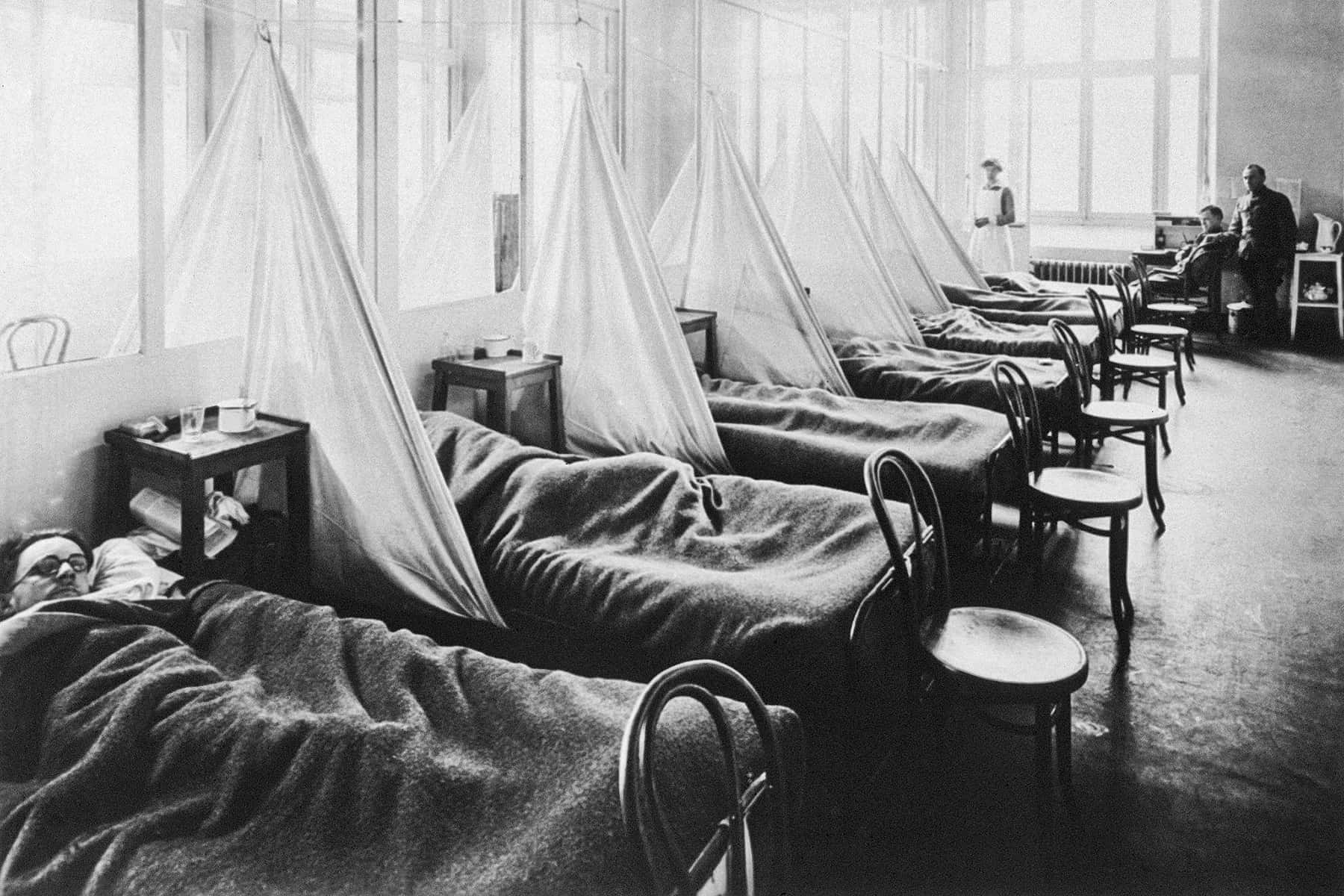

Milwaukeeans marshaled every resource possible to combat the epidemic. Ruhland appointed an advisory committee to oversee the entire campaign. It first moved to expand the city’s hospital facilities. Committee member Dr. Louis Jermain told the Sentinel that Milwaukee had fewer hospitals than any other comparably sized city because most Milwaukeeans received medical treatment at home rather than at a hospital. But with most physicians serving in the military, people would have to go to a hospital or do without treatment. All the city’s hospitals, however, were at or beyond capacity. Temporary space was desperately needed. Accordingly, the advisory committee secured $15,000 each from the County Board of Supervisors and the City Council to convert the vacant Nunnemacher home at 17th Street and Grand Avenue and two halls in the Milwaukee Auditorium into temporary “isolation” hospitals. [6]

Backed by Mayor Dan Hoan, the Common Council and State Health Department, Ruhland adopted extreme measures to check the epidemic. On October 11, he ordered all theaters, movie houses, public dances and indoor amusements closed until further notice. A Milwaukee Sentinel headline summed up Milwaukee’s cheerless mood: “City Again Has ‘Joyless’ Days: Closing of Theaters and Dances Puts ‘Wreck’ in Recreation.” The Health Department went further, shuttering the Washington Park Zoo, Mitchell Park Conservatory, bowling alleys, natatoriums, swimming pools and billiard halls. Ruhland also banned special department store sales, football games, boxing matches, flag-raising ceremonies, political meetings and all other public gatherings. Violators could be fined up to $100 per day; failure to pay the fine could result in imprisonment in the House of Correction for up to six months.

Ruhland also urged residents to avoid crowding in streetcars and elevators and closed two core Milwaukee institutions — saloons and churches — with exceptions. To comply, Archbishop Sebastian Messmer announced there would be no weekday or Sunday Masses; individuals could offer private prayers, providing no large crowd was present. In addition, funerals and weddings could be held only if immediate relatives attended, and priests could hear confessions and give Communion. Saloons could remain open if they did not allow people to congregate. Customers could buy a drink and leave. [7]

Young Rayline Oestreich, a student at the Milwaukee Normal School, noted in her diary that October 13 “sure was a queer Sunday. Not a machine on the street because of the [wartime] gasoline conservation order. All places of amusement closed because of the ‘Flu.’ And so we just stayed home. Read & knit all day. Couldn’t even go to church because they were closed because of the ‘Flu’.” One more Health Department action particularly irritated Rayline. The city closed all 71 public and 61 parochial schools starting Monday, October 14. School Superintendent Milton Potter hoped the children would “find pleasure and profit in reading and playing during this little vacation.” The order, however, did not apply to the Normal School. Rayline went to school that day and groused in her diary, “I think it is mean that normal has to be open when all other schools are closed. Every one has to have his temp taken every day.” [8]

Though more Milwaukee residents undoubtedly grumbled, a host of agencies and individual citizens participated in the city’s wide-ranging mobilization against the flu. School closings enabled teachers to go door-to-door to visit the sick and provide an accurate count of flu cases, an immense help to the Health Department. With the city facing a shortage of medical personnel — a Board member of Johnston Emergency Hospital claimed that one-half of the staff served in the military — Milwaukee’s Public School Board directed physicians and nurses in the schools’ Hygiene Department to assist the short-handed isolation hospitals. The commandant of the Naval Training Station dispatched male nurses to Milwaukee, and women and multiple civic groups helped care for the sick. In addition, the Red Cross motor corps of 18 women and other volunteers provided ambulance services, shuttling the sick from their homes to various hospitals. They answered 875 calls and drove more than 3,000 miles. Anita Weschler praised their work. She saw a nurse and soldier wearing white masks helping a maid into a neighbor’s home and commented, “They are certainly doing a lot more work than they figured on, those motor girls, and they are doing a lot of good at that.”

It was grueling work that placed the caregivers’ lives at risk. Gertrude Kruse, the visiting nurse for the streetcar company’s employee association, made 287 house calls during October. In several cases, she found entire families in bed with the flu. On other occasions, mothers were incapacitated while young children “were running around in night clothes and bare feet. These had to be washed, dressed and fed.” Neighbors failed to assist for fear of catching the dreaded disease. Like Gertrude, Mattie Fuller also wore herself out. She drove an ambulance all day and night on October 14, catching a few hours’ sleep while still in her uniform. For the next three days, she continued the strenuous work, noting on October 17 that she was “Pretty D- tired!” The next day, she went home at noon with the flu. She was in bed with a high fever and pneumonia for a week. The fever finally broke on October 27, and she was able to sit up in bed for a few minutes the next day. Others were not so fortunate. The Milwaukee Journal reported the flu infected 43 nurses laboring in four hospitals, and the Milwaukee County Hospital treated 63 nurses in October who became ill. Several perished. [9]

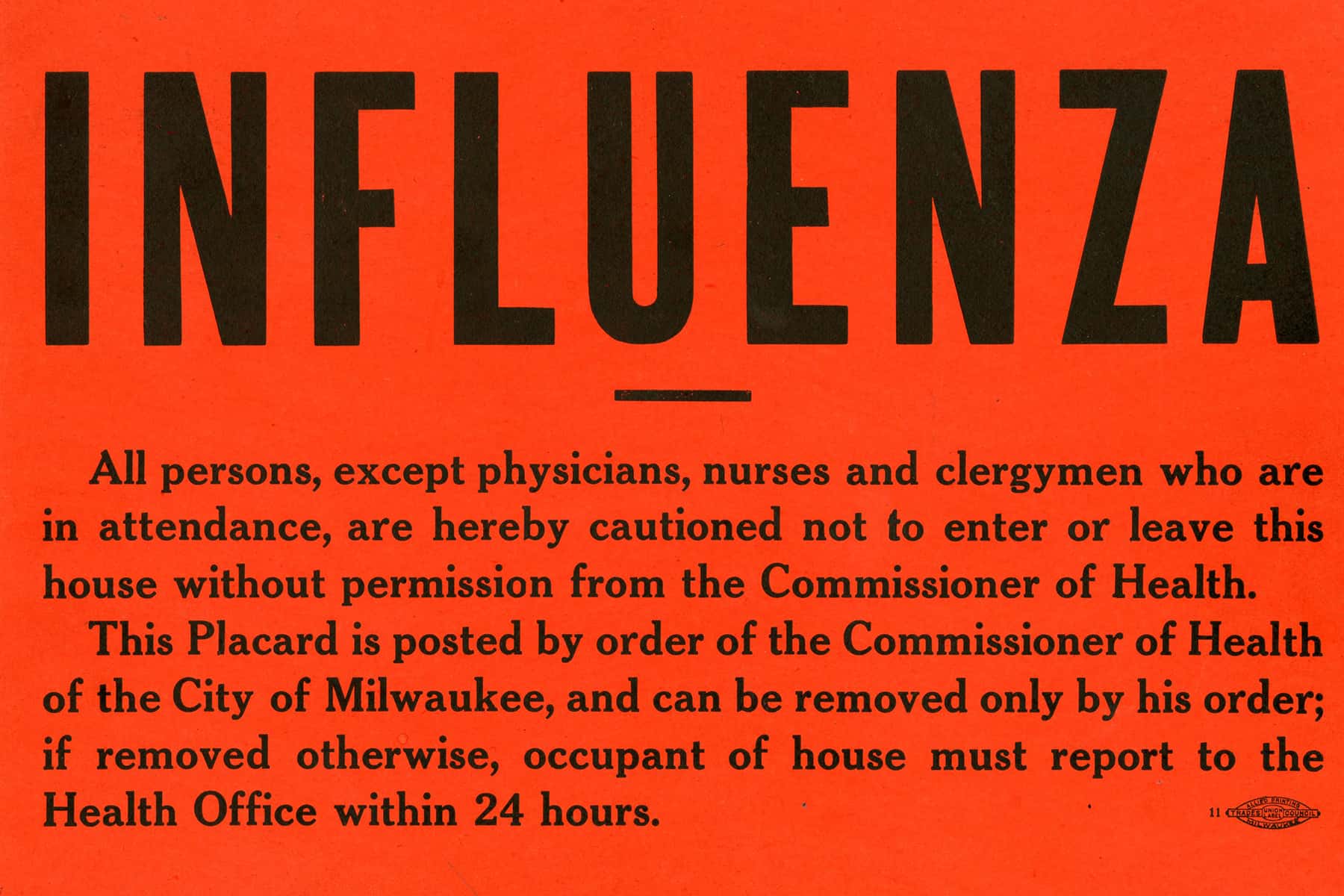

To help mitigate caregivers’ workloads, the Health Department launched a massive educational campaign. In those pre-social media days, this included printed leaflets, posters and placards in several languages to inform the public about steps to avoid contracting the disease. Ruhland provided “talking points” for Milwaukee teachers and clergymen, and appointed speakers visited local factories to give talks during the lunch hour. Policemen assisted by enforcing the spitting ordnance as a means of halting the flu’s spread. Violators were arrested and fined anywhere from $5 to $15. [10]

Despite the city’s best efforts, the epidemic scythed through Milwaukee unabated, peaking at 785 cases on October 14. A week later, Ruhland informed the Common Council that 6,000 cases had been officially reported, but he estimated the actual number was nearly 30,000. Moreover, the number of deaths surpassed 350.

Beyond the health hazard, the epidemic disrupted daily routines of every Milwaukeean. Closure of entertainment venues and retail businesses forced thousands to scramble for temporary work. For example, five burlesque companies — totaling 120 people — from the Gayety and Empress theaters were stranded in Milwaukee. Some of the men toiled in munition factories while several actresses labored in stores or volunteered with the Red Cross. Many, however, could not find work because they could not guarantee how long they would be able to remain at a job; consequently they had to rely on financial support through the Red Cross. Clearly, the pandemic wreaked financial havoc on Milwaukee’s economy. In November, one newspaper estimated that Milwaukee theaters, cafes, dance halls, and other entertainment businesses lost an aggregate $1 million in revenue (roughly $18 million in 2020). [11]

By the end of October, the epidemic had subsided to the point that Ruhland lifted the ban on public gatherings as of November 4. “After a two months’ attack on Milwaukee,” crowed the Journal, “Gen. Spanish Influenza has been forced to acknowledge defeat and accept Health Commissioner Ruhland’s terms for an armistice.” While Ruhland cautioned Milwaukeeans to continue to be careful, avoid crowds and go to bed at the first hint of a cold, he informed Mayor Hoan that the epidemic had ended. City residents, penned up for the better part of three weeks, needed little prodding to flood into the streets and resume their normal lives. But not everyone heeded Ruhland’s warning about avoiding crowds. Hundreds of Milwaukee citizens gathered on the slopes of Juneau Park to have themselves filmed as part of a “joy reel” to be shown to Milwaukee soldiers overseas. The city’s movie theaters also did a very brisk business. One Marquette University student visited four theaters in one evening, “’Making up for what [he] missed while [he] had the flu.’” [12]

Lifting the ban on November 4 — one day before the fall 1918 election — also signaled the start of a day of frenzied political campaigning. Throughout the fall, the influenza epidemic prevented frustrated politicians from staging the usual spate of political rallies. The Journal related tongue-in-cheek that “Politicians have suffered more, perhaps, than anyone else. For three weeks they have been filled with red-hot speeches and have been denied the privilege of an audience.” Instead, all sides were limited to the usual partisan bickering in newspapers, campaign flyers and posters. But once unshackled by the lifting of the ban, the Sentinel anticipated “one big bang” as all candidates would “tear loose with that one and only speech with which they expect to capture many votes in the present ‘speechless’ campaign.”

Election day was equally frenetic, and the results were disastrous for Democrats. Republican Governor Emanuel Philipp handily won re-election as governor, and the Republicans won 10 of the state’s 11 Congressional seats. Socialist Victor Berger captured the other Congressional seat, despite being under indictment for violating the wartime Espionage Act. In fact, the Socialists swept a whole slate of county and city offices and sent several members to the State Assembly. The Free Press deemed the election a “Socialist avalanche,” confirming Milwaukee citizen’s weariness of wartime food and fuel regulations, unrelenting criticism of the city’s German-Americans, and the silencing of any critics of the war effort. [13]

Believing the epidemic over, Milwaukee residents prayed for a reason — any reason — to celebrate life. Their prayers were answered on November 7. Shortly after noon, newsboys began shouting “Extra! Extra! The War Is Over. Germany Surrenders.” The Milwaukee Sentinel brought out an extra edition that stated the war would end at 2:00 p.m. The Leader, Evening Wisconsin, and Milwaukee Daily News likewise issued extras announcing the end of the war. By 12:30, whistles all over the city began blowing, car horns blared and throngs of jubilant people crowded downtown streets. Someone in a downtown office building opened a window and threw out a basketful of shredded paper. Others followed suit, and soon the streets “resembled the aftermath of a snow storm.” Businesses declared a half-holiday, and their employees launched impromptu parades all over the city. Festivities carried on well into the night, as revelers lit bonfires that made Grand Avenue look as if it were “ablaze with red fire.” [14]

The unbridled joy convinced Rayline Oestreich that the city had “gone mad, simply mad.” Anita Nunnemacher Weschler rescheduled a dentist appointment because her dentist was so excited that “he was afraid that if he did any work that day, he would risk all his patients.” Both she and Anita Weschler worried the news was too good to be true. It was. A United Press reporter in France had accepted a false cable as fact and immediately spread news of the war’s end to the United States. [15]

The false alarm prompted a good deal of grousing, but distraught locals did not have to wait long for their spirits to be lifted. Shrill factory whistles and wild shouting in the streets awakened everyone at 2:30 a.m. on November 11. Assured that the armistice had indeed been signed, Milwaukee again experienced a spree of boisterous partying. Grand Avenue was packed by 3:00 a.m., and Harbor Commissioner and Milwaukee historian William George Bruce arrived downtown in the morning to find clouds of scrap paper raining down from office buildings. Numerous improvised parades marched up and down downtown streets, and Bruce noted the “liquids folwed [sic] freely” as untold numbers of glasses were raised to toast the end of the war. Bruce joined a lunch crowd at the Athletic Club and narrowly avoided becoming a “hilarious drunk,” something he had never been guilty of, by “escaping stealthily.” The celebrations, he observed, “ran to a hysterical degree.” And why not? he asked for it was “the greatest day in the history of the world!” [16]

The war’s end temporarily blocked thoughts of the Spanish Flu, but its specter continued to haunt Milwaukee. Health Commissioner Ruhland acknowledged there would be flu cases all winter, but Milwaukeeans did not need to worry about the resurgence of epidemic levels. He changed his tune, however, in a matter of two weeks. The virus mutated once again, launching a third wave that engulfed the country. On November 14, the number of flu cases in Milwaukee had dropped to 64, but the figure climbed steadily thereafter, forcing Ruhland to recall his advisory committee, re-open the Nunnemacher Hospital and warn Milwaukee citizens that the flu had returned. He advised citizens to not hold Thanksgiving parties and asked schools to cancel all non-essential social functions. These halting steps did not stop the disease from returning with a vengeance. During the first week of December, flu cases hovered between 264 to 386 per day; the number peaked at 647 on December 10. The December 4 Journal included a full-page ad in which Ruhland scolded Milwaukeeans: “In spite of the repeated warnings of this office, there has been a laxity on the part of the Milwaukee Public in taking precautions to prevent the spreading of Influenza.” If city residents did not voluntarily take steps to avoid an even more serious outbreak, Ruhland threatened to close all public gathering places. [17]

The flu’s resurgence added fuel to rumors that it was a “foreign” virus. Some claimed the Germans brought the disease to the U.S. in a submarine operating along the coast, and that a crew came ashore and released the germ. One Milwaukee woman wanted Mayor Hoan to stop the “talk” about the flu in the newspapers. “In the first place,” she argued, “the whole thing is German propaganda.” The Germans could not defeat the Americans in the war; consequently, “they planned this attack not only on the soldiers but on the whole American people and here our health boards and papers all fall for it and help to spread the thing by having those great head lines [sic] and pages of scare heads and telling how many cases there are.” The country’s best bacteriologists had not found the germ of this “so-called disease,” so would it not be wiser, she asked, “for the health department to THINK RIGHT about this matter and stop spreading disease thought germs and augmenting the fear of the people?” [18]

Fortunately, most Milwaukee residents followed the health commissioner’s instructions — at least well enough that Ruhland never issued a full ban. The Health Department did, however, take several steps to curb the epidemic. It urged residents to wear masks and quarantined infected households, posting bright red “INFLUENZA” signs on them. It required theaters and churches to reduce attendance by roughly 50 percent by filling alternate seats and excluding children under 15 years old. Ruhland closed schools and libraries, and forbid crowding on streetcars and in stores. The poor timing was not lost on William George Bruce. He noted on December 15 that the “sun shines brightly this morning on an influenza stricken community. Never in the history of the city have so many cases of illness been reported….And here it is ten days before Christmas when people are expected to do their shopping in crowded stores and move about in crowded street cars.” Realizing city stores would be tempted to ignore the no-crowding order during the height of the Christmas shopping season, the Health Department stationed inspectors at the most prominent establishments. Most businesses and individual citizens cooperated with Ruhland’s crusade, but the Health Department investigated quite a few reports of department stores violating the no-crowding rule. [12]

By Christmas Day, the epidemic had essentially run its course. Ruhland lifted the ban on large gatherings, and schools re-opened on January 2. At the close of the year, the disease had killed 1,173 Milwaukeeans — 23 percent of all flu-related deaths in Wisconsin. Oddly enough, the flu did not prey on the very young or very old; most victims were in the 15-40 age bracket. While the death toll was alarming, Milwaukee’s death rate — 2.56 per 1,000 — was the second-best ratio in the country. Population density and climate may account for Milwaukee’s success, but the Health Department’s aggressive measures and cooperation of political leaders, civic organizations and general public deserved a good deal of credit for reducing the epidemic’s impact. Nevertheless, the epidemic exacted a tremendous emotional and economic toll, not to mention the unfulfilled potential of those who perished. [19]

The current coronavirus pandemic is an equally elusive danger. Hopefully, the number of deaths will be no where near Spanish Flu levels, but, if anything can be learned from the 1918 crisis, it is that proactive, concerted and determined action, along with shared sacrifices and cooperation will be necessary to blunt the disease’s devastation.

Kevin Abing, PhD

An excerpt from A Crowded Hour: Milwaukee during the Great War, 1917-1918 by Kevin Abing

- John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (New York: Viking, 2004), 4-5, 396-98.

- Steven Burg, “Wisconsin and the Great Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918,” Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 84, no. 1 (autumn 2000): 39, 41-42; Alfred W. Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 17-55; Nancy K. Bristow, American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 3-4, 43-45; Barry, The Great Influenza, 91-99, 169-93.

- “New Disease in Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Journal, September 16, 1918.

- Barry, The Great Influenza, 201-2, 335-38; Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic, 57; “Prepare to Battle 100 Cases Here of Spanish Influenza,” Milwaukee Leader, September 21, 1918; “Jackies Blamed for Influenza,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 18, 1918; “Hundred Ill of Influenza in Milwaukee,” ibid., September 25, 1918; “Influenza Checked at Great Lakes,” ibid., September 23, 1918; “Boston Schools Closed as Epidemic Takes Toll of 100 Dead in 24 Hours,” ibid., September 24, 1918; “Spanish Influenza May Stop ‘Shore Leave’,” Milwaukee Journal, September 18, 1918; “Flue is the Grip,” ibid., October 1, 1918.

- “Liberty Loan Drive to Open Saturday with Huge Parade,” September 27, 1918, in “Liberty Bonds,” Milwaukee Features Microfilm; “Take $600,000 in Liberty Bonds,” Milwaukee Journal, September 28, 1918; “Vast Throngs Cheer City’s Loan Pageant,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 29, 1918; “25,000 Take Part in Parade Opening Liberty Bond Campaign,” Milwaukee Journal, September 29, 1918; Anita Weschler to Edward Weschler, September 23, 1918, September 25, 1918, and October 1, 1918, Nunnemacher/Weschler Family Papers, Box 4, File 99 and File 100; “Drastic Steps to Check Influenza,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 6, 1918.

- “Facilities Scarce in City Hospitals” and “Spanish Grippe Epidemic Grows,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 7, 1918; “Ruhland Sounds Warning on ‘Flu’” and “Influenza May Close City Schools,” ibid., October 8, 1918; “Unite Forces to Check Influenza,” ibid., October 9, 1918; Bulletin of the Milwaukee Health Department, vol. 8, no. 10-11 (October-November 1918): 3-4; Proceedings of the Common Council of the City of Milwaukee, October 9, 1918.

- “Disease Peril Rouses Whole City to Fight,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 10, 1918; “City Starts Big Battle on Influenza,” “Theaters Hard Hit by Closing Order,” “Influenza Closing Order Broadened by Dr. Ruhland; Public Funerals Banned,” and “City Again has ‘Joyless’ Days,” ibid., October 11, 1918; “City Extends Grippe Edict on Meetings” and “Schools Ordered Closed by Dr. Ruhland in City’s Fight on Influenza Peril,” ibid., October 12, 1918; Proceedings of the Common Council of the City of Milwaukee, October 9, 1918; Burg, “Wisconsin and the Great Spanish Flu Epidemic,” 47; Judith Walzer Leavitt, The Healthiest City: Milwaukee and the Politics of Health Reform (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1982), 229-31.

- October 13-14, 1918 diary entries, Rayline D. Oestreich Papers, MCHS, Box 2.

- “Disease Peril Rouses Whole City to Fight,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 10, 1918; “Schools Ordered Closed by Dr. Ruhland in City’s Fight on Influenza Peril,” ibid., October 12, 1918; Proceedings of the Board of School Directors, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, July 1st, 1918—June 30th, 1919, 121-23; Burg, “Wisconsin and the Great Spanish Flu Epidemic,” 47-48; Proceedings of the Common Council of the City of Milwaukee for the Year Ending April 15, 1919, 554; Captain W.A. Moffet to Dan Hoan, October 10, 1918 and report of George C. Ruhland, October 21, 1918, in Hoan Collection, Box 18, File 427; Leavitt, The Healthiest City, 232-33; “An Active Month,” Rail and Wire, December 1918, Milwaukee County Transit Collection, MCHS, Box 3, File 3; October diary entries, Clyde and Mattie Fuller Collection, MCHS; “Fail To Report ‘Flu’ Cases,” Milwaukee Journal, October 15, 1918; Anita Weschler to Edward Weschler, October 25, 1918, Nunnemacher/Weschler Family Papers, MCHS Box 4, File 100; Milwaukee County Hospital Female Register, 1917, Milwaukee County, Institutions and Departments Collection, MCHS.

- Burg, “Wisconsin and the Great Spanish Flu Epidemic,” 47-48; “Influenza May Close City Schools,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 8, 1918; “Whole City to Fight ‘Flu’,” Milwaukee Journal, October 8, 1918; The Conveyor, November 1918, Milwaukee Coke and Gas Company Collection; “City Extends Grippe Edict on Meetings,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 12, 1918; “Eight Pay $5 Fines in Anti-Spitting Crusade,” Milwaukee Journal, October 12, 1918.

- George Ruhland to the Common Council, October 21, 1918, Hoan Collection, Box 18, File 427; Bulletin of the Milwaukee Health Department, vol. 8, no. 10-11 (October-November 1918): 3-4; “Many Actresses in Stores While Influenza Ban On,” Milwaukee Leader, October 28, 1918; “Influenza Ban Off Tomorrow; Loss $1,000,000,” November 3, 1918, clipping, Falk Collection, Box 1, Scrapbook, 1917-1923; “Red Cross Provides Funds for Actors,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 7, 1918; Hoan to William Schmidt, December 7, 1918, Hoan Collection, Box 18, File 427.

- “’Gen. Influenza’ Surrenders,” Milwaukee Journal, November 3, 1918; Leavitt, The Healthiest City, 233; Proceedings of the Common Council of the City of Milwaukee for the Year Ending April 15, 1919, 587-88; Ruhland to Dan Hoan, November 8, 1918, Hoan Collection, Box 18, File 427; Marquette Tribune, November 7, 1918; “Heaven’s Tears Mingle with Milwaukee Smiles for Boys ‘Over There’,” Milwaukee Free Press, November 4, 1918; “All Theaters Reopen to Capacity Crowds,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 5, 1918.

- Thomas Fleming, The Illusion of Victory: America in World War I (New York: Basic Books, 2003), 291-93; Paul W. Glad, The History of Wisconsin, vol. V: War, a New Era, and Depression, 1914-1940, gen ed. William Fletcher Thompson (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1990), 50-53; George F. Kull to My Dear Mr., October 9, 1918 and Wheeler Bloodgood to Kull, October 9, 1918, both in Wisconsin, War History Commission Collection, Series 1706, Box 1, File: Minutes, 1917-1918; F.W. Rehfield to Dear Sir, October 18, 1918, Socialist Party Collection, Box 8, File 199; Milwaukee Leader, October 28, 1918; “Candidates Plan Rousing Finish,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 1, 1918; “Gen. Influenza Surrenders,” Milwaukee Journal, November 3, 1918; Milwaukee Free Press, November 6, 1918; Kennedy, Over Here, 240-41; “Socialists Ready for Poster Vandal,” Milwaukee Leader, October 24, 1918; Lorin Lee Cary, “The Wisconsin Loyalty Legion, 1917-1918,” Wisconsin Magazine of History, vol. 53, no. 1 (autumn 1969): 45-50; John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee, WI: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 230; Sally M. Miller, Victor Berger and the Promise of Constructive Socialism, 1910-1920 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, Inc., 1973), 206-7.

- “War is at End,” Milwaukee Leader, November 7, 1918; “Germany Surrenders,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 7, 1918; “City Thrown into Delirium of Peace Joy,” ibid., November 8, 1918; “Milwaukee Goes Wild over News That War has Come to an End,” November 7, 1918, clipping in John G. Gregory Collection, MCHA, Box 4a.

- “Milwaukee Goes Wild over News That War has Come to an End,” November 7, 1918, clipping in Gregory Collection, Box 4a; William George Bruce, “Days with Children,” 1918, Part II, 56-57, William George Bruce Collection, MCHS; diary entry, Oestreich Collection; Anita Weschler to Edward Weschler, November 7, 1918, Nunnemacher/Weschler Collection, Box 4, File 101.

- Bruce, “Days With Children,” 1918, Part II, 67-68, Bruce Collection; “City to Stage Huge Parade,” “’Der Tag’ in Milwaukee” and “Kaiser Sentenced to be Hanged in Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Journal, November 11, 1918; Robert W. Wells, This is Milwaukee (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1970), 187-89.

- “Flu Danger Past, Says Ruhland,” Milwaukee Journal, November 14, 1918; Milwaukee Leader, November 28, 1918, in Stern Papers, Box 16, File 11; “Flu Situation Getting More Serious,” Milwaukee Journal, November 29, 1918; Bruce, “Days with Children,” 1918, Part II, 88, Bruce Collection; Ruhland advertisement, Milwaukee Journal, December 4, 1918.

- The Conveyor, November 1918, Milwaukee Coke and Gas Company Collection, MCHS; Imogene Weatherbee to Dan Hoan, December 12, 1918, Hoan Collection, Box 9, File 229.

- Burg, “Wisconsin and the Great Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918,” 38-41, 50-51, 55; Leavitt, The Healthiest City, 237-39; Annual Report of the Commissioner of Health of the City of Milwaukee, 1918, 3, 75, 77; “City Second in Flu Fight,” Milwaukee Journal, December 31, 1918; Crosby, America’s Forgotten Pandemic, 311-325.

Library of Congress and Milwaukee County Historical Society