President Joe Biden’s administration announced in December that it was ramping up efforts to help house people sleeping on sidewalks, in tents, and cars as a federal report confirmed what was obvious to people in many cities: Homelessness is persisting despite increased local efforts.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development said that in federally required tallies taken across the country earlier in 2022, about 582,000 people were counted as homeless — a number that misses some people and does not include those staying with friends or family because they do not have a place of their own.

The figure was nearly the same as it was in a survey conducted in early 2020, just before the coronavirus pandemic hit the nation hard. It was up by about 2,000 people — an increase of less than 1%. The administration aims to lower that by 25% by 2025.

“My plan offers a roadmap for not only getting people into housing but also ensuring that they have access to the support, services, and income that allow them to thrive,” Biden said in a statement.

The 2022 All In strategy roadmap made public Monday follows a 2010 effort called Opening Doors, which was the nation’s first comprehensive strategy seeking to prevent and end homelessness.

Ann Oliva, CEO of the National Alliance to End Homelessness and a former HUD executive who worked on the first roadmap, said the federal government can influence local action with financial incentives, streamlined processes and strong policies.

Homelessness among veterans, for example, has plummeted as a result of federal leadership, and the country has also made inroads among youth, she said.

“What they’re trying to do here is to show, as a federal government, we are going to work across agencies, we’re going to break down silos, we’re going to lead with equity, we are going to talk about upstream prevention and work on those issues,” Oliva said.

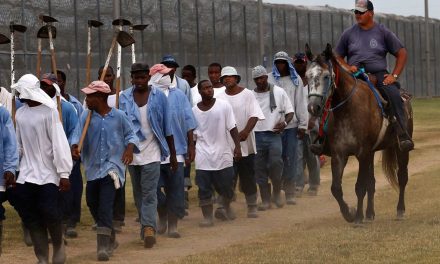

The federal plan highlights racial and other disparities that have led to inequity in homelessness. It seeks to expand the supply of affordable housing and improve on ways to prevent people from becoming homeless in the first place.

Potential steps include a campaign to encourage more landlords to accept government housing vouchers and encourage local governments to build more apartment complexes that are affordable for working families.

The administration also announced a program to have federal agencies work with local officials to reduce unsheltered homelessness in select cities that have not yet been named.

Homelessness has become a major political issue, especially in the nation’s biggest cities and on the West Coast. Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass took office last month and promptly declared a state of emergency. New York Mayor Eric Adams in November announced a plan to treat mentally ill people and remove them from the streets and subways, even against their will.

The Point in Time survey for 2022 reflected a balancing of opposing forces. The pandemic brought massive job losses, particularly for lower-income people, and higher rents. It also spurred an eviction moratorium and temporary federal aid, including tax credits for families that helped keep people housed.

The count found homelessness declined among veterans, families, children and young adults. But more people were staying in places not intended for habitation rather than shelters, and more had been homeless for more than a year. Black people continued to be disproportionately likely to be homeless.

The new count was heavily anticipated because the 2021 survey was incomplete due to the pandemic. The 2022 survey was not a full return to normal, however. While the individual tallies normally take place in late January, many were pushed back to February or March because of the pandemic. The local reports compiled into the national data showed the numbers rose some places and fell in others.