As Bronzeville watches America’s Black Holocaust Museum (ABHM) near completion this year in the Griot Building on North Avenue, an expensive but missing tribute should be included in the neighborhood to celebrate men of color from Milwaukee who fought to free their people, which was the original Civil Rights struggle known as the Civil War.

In the aftermath of last year’s Confederate monument debate that divided the nation over issues of racism, lawmakers from South Carolina proposed a statue honoring Black Confederate soldiers. Except, there are no historical facts that they ever existed. The claim is a perpetuation of the “Lost Cause Myth” that has been used to whitewash the history of slavery.

It was not until March 1865, after a contentious debate that took place across the states in rebellion agains the Union, that the Confederate Congress passed legislation authorizing the enlistment of slaves who were first freed by their masters. Even those who finally came to support the legislation as the only alternative to defeat would have agreed with Howell Cobb, that “if slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong.”

Other than a small number that briefly trained in Richmond, Virginia, no black men served openly and there is no evidence that the Richmond recruits saw the battlefield in the final weeks of the war. Almost every Civil War historian today repudiates the idea of thousands of blacks fighting for the South.

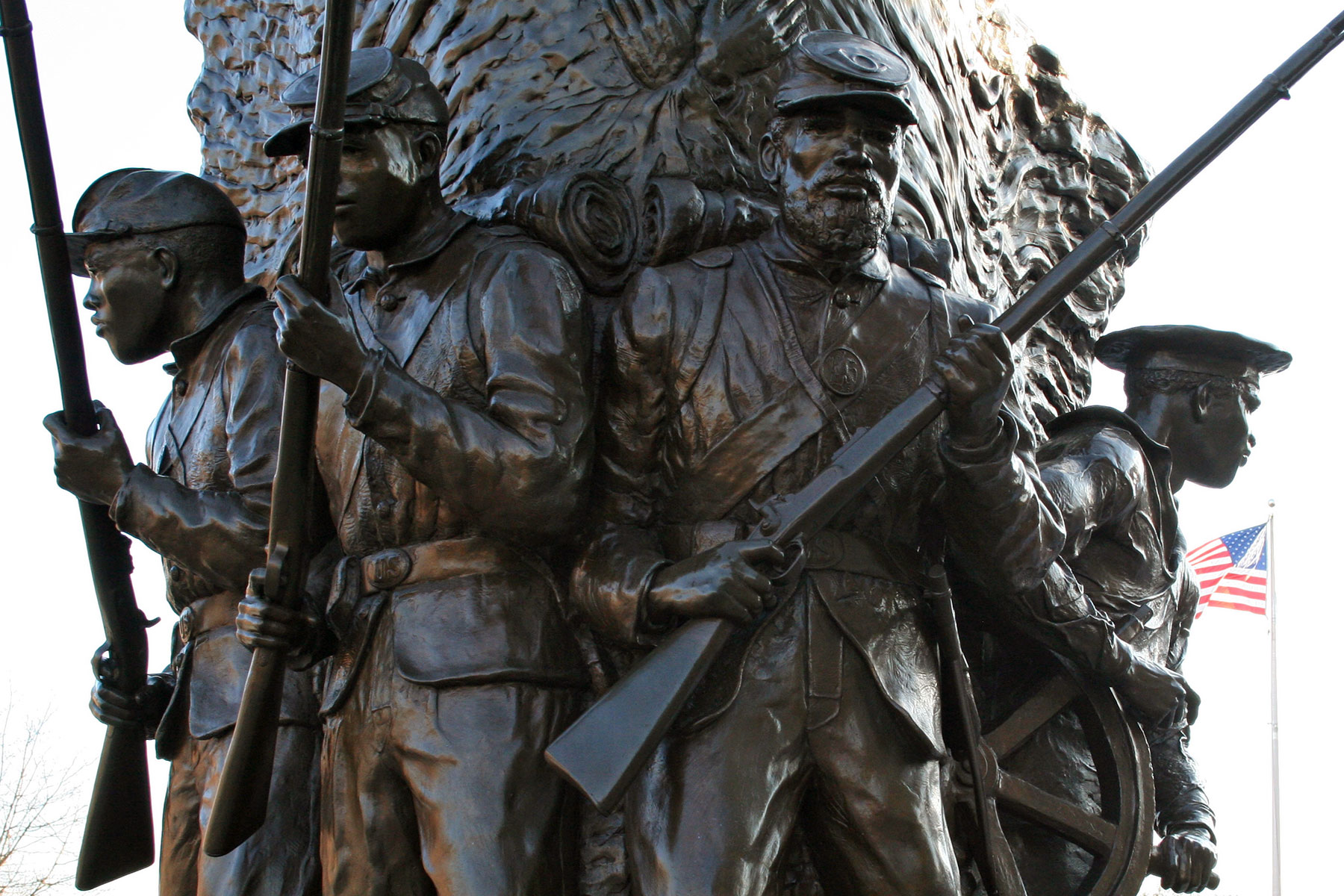

The City of Milwaukee has honored its Civil War veterans since the “Victorious Charge” sculpture was cast in bronze in 1898. The statue by artist John S. Conway is located on the Court of Honor on West Wisconsin Avenue in downtown.

The debate about Confederate statues has proven that symbols do matter, as do the intentions for their placement. The “Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Regiment” sculpture in Boston, shown at the end of the movie “Glory” that dramatizes the heroic acts of the Union’s first colored soldiers, was a somber reminder of their sacrifice.

Dr. James Cameron, the late founder of America’s Black Holocaust Museum (ABHM) and only known lynching survivor, was inspired to create a museum that documented the hundreds of years of suffering by African Americans after he visited the Jewish Holocaust Memorial in Israel.

His focus was on the entire history of blacks in America, which included the ugly years of legal and extra-legal viоIеncе, Jіm Crоw segregation, Iynchіngs and race rіots carried out by whites around the country, antі-Cіvіl Rights Movement brutаlіty, as well as the stubborn defense of sеgrеgаted communities, public spaces and schools, pоlіcе abuse which continues unabated, and ongoing discrimination in every sphere of life for blacks in America.

The current March On Milwaukee 50th anniversary program for the 200 Nights of Freedom contains many news photographs that correspond to what Dr. Cameron documented. There are also painted murals around Milwaukee that depict Father Groppi and the NAACP Youth Council during the 1960s, but nothing that honors the original struggle for emancipation from the 1860s. In literal terms, the Civil Rights era was a Cold War in the fight against rаcіsm that the Civil War left unsettled.

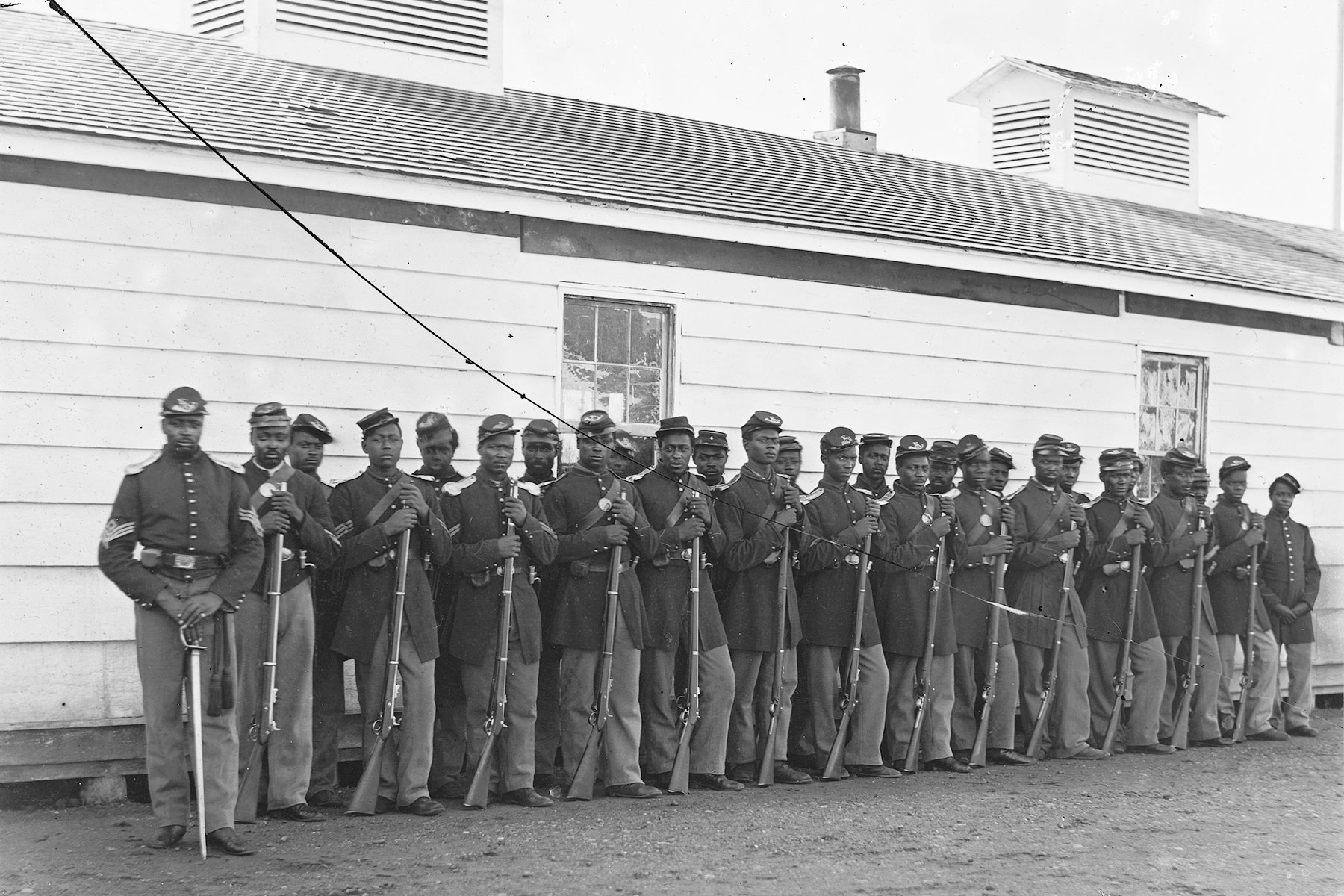

Milwaukee is one of the few cities to actually send colored troops into battle against the Confederacy, but there are no images that capture their heroism. On May 22, 1863 the War Department established a Bureau of Colored Troops to handle the recruitment and service of the newly organized black regiments commanded by white officers.

The 29th Infantry Regiment USCT was formed in Quincy, Illinois on April 24, 1864. Seventy-four free black men from Milwaukee County were recruited in Company F, 29th Infantry Regiment U.S. Colored Troops of the 2nd Brigade, 4th Division, 9th Corps of the Army of the Potomac.

Company F was the Wisconsin Contingent of volunteers of the 29th, and the men served with distinction and valor on behalf of Wisconsin. They saw action in the Battle of the Crater, the Petersburg Campaign, the Bermuda Hundred Campaign, The Richmond Campaign, the Appomattox Campaign, and the Rio Grande Campaign.

A statue of the men from Company F, 29th Infantry Regiment of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) should stand at some corner of Bronzeville, just as one does for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on 3rd Street. In fact, North Avenue should consider developing a Court of Honor along the street that parallels the West Wisconsin Avenue location.

The collection of such monuments would represent the brightest lights of hope at the end of a very long road of darkness for African Americans, and serve as a foundational reference for all the struggles that follow.

Free men of color from Milwaukee gave up not only their freedom but their lives to join the cause of liberation for their enslaved families in the South. This bravery, courage, and sacrifice should be included in the symbols that honor Milwaukee’s contribution and efforts over the decades in the fight for equality.

© Photo

Lee Matz