For generations, the United States has used federal policy not only to distribute land, property, and wealth, but to do so along racial lines.

While the narrative of American meritocracy champions hard work and self-reliance, the historical record tells a different story: White Americans were repeatedly granted free or subsidized land, monetary benefits, and structural advantages through government action, often at the direct expense of Indigenous, Black, Mexican, and Asian communities.

The economic divide that persists today is not the result of personal failure. It is the predictable outcome of decades of legalized racial preference.

Long before the founding of the United States, White settlers were accumulating land through government-backed schemes. One of the earliest examples was the headright system, implemented in colonial Virginia in 1618.

Under that policy, White landowners were awarded 50 acres of land for every indentured servant or enslaved African they transported to the colonies. In 1638, George Menefie secured 3,000 acres after importing 60 enslaved people, land stolen from Indigenous nations, and granted to a plantation economy that would come to define the American South.

The system not only rewarded White settlers for importing human labor, but it also formalized a racial caste.

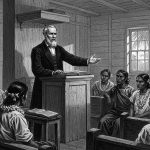

The 1705 Act Concerning Servants and Slaves exemplifies the dual system of uplift and oppression.

While European indentured servants were freed and given land, clothing, and tools, including up to 50 acres and a musket, Black laborers were permanently enslaved. As historian Ira Berlin noted, “freedom and slavery were created at the same moment.”

It was not a contradiction but a design: White freedom required Black unfreedom.

As the nation expanded, so did White access to land, and often violently. In 1830, the Indian Removal Act authorized the forced expulsion of Indigenous tribes from lands east of the Mississippi River.

The policy was not just about displacement. It was about economic transfer. Approximately 25 million acres of tribal land was redistributed, primarily to White settlers and plantation owners. The expansion of slavery followed, as cotton agriculture took root in these newly “opened” lands.

When the United States absorbed half of Mexico’s territory under the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the official treaty promised to honor the land rights of Mexicans in annexed regions. In practice, however, White settlers, with the support of U.S. courts, militias, and local officials, systematically stripped Mexican landowners of their property through legal maneuvering, violence, and fraud.

The discovery of gold in California just before the treaty was signed only intensified the pressure to remove Mexican landholders and Indigenous Californians.

By the time of the 1862 Homestead Act, land redistribution to White settlers had become fully institutionalized. That act offered up to 160 acres to anyone, almost always White, who could live on and cultivate the land for five years.

The price was nominal: $1.25 per acre. Over 270 million acres of land, much of it Indigenous, was handed out. Homesteading programs were explicitly built on racial exclusion. Black Americans were technically eligible but faced organized violence, fraud, and state neglect that rendered the law almost entirely ineffective for them.

Native Americans, whose lands were being handed out in the first place, had no say at all.

Even when slavery was abolished, White wealth was prioritized. Under the District of Columbia Emancipation Act, the U.S. government paid $300 per enslaved person in compensation to former slaveholders.

Those who had profited off human bondage were rewarded again for the loss of their “property.” The formerly enslaved, whose unpaid labor built the wealth of a nation, received nothing.

In 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Act, which was pitched as a reform measure to “help” Indigenous people assimilate by granting them individual plots of land. In reality, it dismantled communal ownership, undermined tribal sovereignty, and imposed a patriarchal structure alien to many Indigenous societies.

Any “surplus” land not allocated to Indigenous families was sold to White settlers. By 1932, White Americans had acquired two-thirds of the 138 million acres originally allocated to tribes under the act.

Land was not the only pathway to White generational wealth. The National Housing Act of 1934 created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which backed low-interest home loans with long repayment periods, an unprecedented opportunity to build middle-class security.

But this system was constructed on redlining, restrictive covenants, and overt racial exclusion. While over $120 billion in housing wealth was created between 1934 and 1962, less than 2% of that went to non-White families.

Black, Latino, Asian, and Indigenous people were routinely denied loans or steered into segregated neighborhoods with declining property values. Homeownership became the cornerstone of generational wealth for White Americans. For everyone else, it remained out of reach.

Over and over, American policy used land, law, and subsidies to generate White prosperity. These were not accidents or unintended consequences. They were targeted interventions to engineer a racial hierarchy with economic consequences that persist into the present day.

The result of these compounding advantages is the modern racial wealth gap. According to 2022 data from the Federal Reserve, the median White household holds nearly ten times the wealth of the median Black household, and more than eight times that of the median Latino household.

Indigenous and many Asian American communities face similar disparities, though aggregated statistics often mask wide variation within Asian groups. These gaps are not just numbers. They reflect real-world inequalities in homeownership, education, retirement security, business investment, and intergenerational mobility.

Wealth determines who can buy a home, start a business, weather a crisis, or fund a college education without incurring debt. It determines who can help their children buy their first property, who inherits assets, and who gets stuck paying for the systemic failures of the past.

When the United States provided massive land grants and housing assistance to White Americans, while excluding or dispossessing communities of color, it set in motion a self-reinforcing cycle. Today’s wealth disparities are not simply echoes of history. They are the direct consequence of deliberate policy.

This legacy is often omitted from national debates over fairness and opportunity. Instead, the conversation is repeatedly steered toward personal responsibility, cultural pathology, or merit. But none of these narratives explain how White Americans came to hold the vast majority of private land, capital, and housing wealth in a country built on stolen labor and territory.

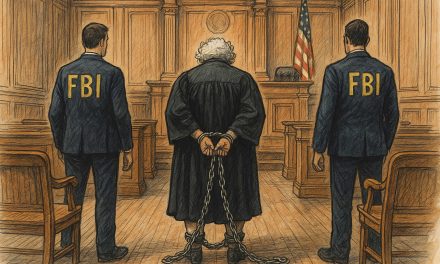

The wealth gap is not a glitch in the system. It is the system. And yet, the political response to confronting that history, and attempting even modest remedies, has been swift and hostile.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives, which in many cases amount to little more than hiring goals, cultural awareness training, or scholarship funds, have been turned into political punching bags. The same country that spent hundreds of years creating a racialized economy now recoils at the suggestion that fairness might require intentional correction.

In 2023 and 2024, Republican lawmakers across more than two dozen states introduced legislation to ban or defund DEI programs in public institutions. They claimed such efforts amounted to “reverse racism,” “Marxism,” or even “anti-American indoctrination.”

Corporate executives were pressured to retreat from racial equity commitments made after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Conservative legal groups began suing over workplace diversity programs, and right-wing media launched campaigns to cast DEI as discriminatory.

This manufactured backlash served a dual purpose: it defended entrenched racial hierarchies while redirecting the anger of White Americans away from the true sources of their frustration. The stagnation of wages, the collapse of rural economies, the unaffordability of housing, the burden of medical debt — none of these are caused by Black college students, Indigenous land acknowledgments, or Hispanic entrepreneurs.

They are caused by a decades-long upward redistribution of wealth to corporations, billionaires, and Wall Street, aided by and accelerated under Republican rule.

By inflaming White grievance against symbolic efforts at equity, the Republican political machine has managed to shield the country’s richest and most powerful actors from scrutiny. Instead of investigating why entire communities have lost factories, pensions, and schools, the focus is shifted to whether a university hired a DEI consultant or a government agency published a diversity report.

The conversation moved from structural justice to imagined slights. Such political tactics are not new. Historically, whenever American society has moved toward justice, from Reconstruction to the civil rights era, White backlash has followed.

What’s different now is how efficiently grievance politics has been weaponized not just to oppose progress, but to confuse and fracture the working class. By selling White identity politics as a replacement for economic policy, the Republican Party offers White Americans a scapegoat, not a solution.

Meanwhile, the wealth generated by a couple centuries of land theft, labor exploitation, and racial exclusion continues to compound. The average Black family would need 228 years to reach the level of wealth currently held by the average White family, assuming no changes in policy. That gap is not closing on its own. It was created through government action, and only government intervention can reverse it.

Yet instead of reckoning with this reality, the nation is engaged in a campaign of denial.

Republican politicians have outlawed the teaching of history, corporations retreat from accountability, and media coverage often frames the wealth gap as a mystery or a tragedy, rather than a policy outcome.

As a result, the very people harmed most by economic inequality are too often divided by narratives designed to keep them from organizing around shared interests.

The future of economic justice in America depends on telling the truth. Not just about what was done to people of color, but about what was given — freely, repeatedly, and overwhelmingly — to White Americans.

Only by acknowledging the systems that built inequality can we dismantle them. Anything less is not a debate about fairness. It is a refusal to face the nation we truly are, and the country we might still become.

© Photo

EWY Media and Sherry Saye (via Shutterstock)