“Interdependence is and ought to be as much the ideal of man as self-sufficiency. Man is a social being.” – Mahatma Gandhi

“India is the world’s oldest continuous civilization.” I heard this thought-provoking statement a number of times when I traveled to India with my wife, son, and in-laws in February.

As I reflected on the significance of a people living together, building community and culture for millennia in resistance to or temporary co-existence with would-be conquerors and colonizers, I was moved by the idea of such deep connection to one another and one’s identity to make such a historical reality possible.

This idea gave me an even greater appreciation for the deep roots in India of my wife’s generational relationships, my mother-in-law’s family from Gujarat, my father-in-law’s family from Punjab – and how they have grown into our family’s connection with the country.

Our sons have known India since they were very young, which has created a sense of belonging with its people and culture. While my wife and son had traveled recently to India, I had not been back since 2015. I was excited to see India through my fourteen-year-old son’s eyes, and how things might have changed during the past nine years.

I was also curious to experience India through the lens of social connectedness, as the rise of social isolation in the United States has been at the forefront of my work over the past year. I wondered if India might be experiencing similar challenges or if its complex and rich history as the oldest continuous civilization might lead me down pathways toward social connectedness.

The Importance of Social Connectedness

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, social connectedness is defined as the relationships people or groups have, that lead to a sense of belonging, being cared for, valued, and supported. When individuals are socially connected, they are better able to navigate life challenges and cope with stress, trauma, anxiety, and depression. Being connected to others can help reduce feelings of loneliness and isolation, and can provide support during difficult times.

When we feel valued and accepted by a community, we develop a greater sense of belonging that can create purpose and identity. Being part of a supportive group can encourage individuals to make healthier choices, physically, mentally, and socially.

The Toll of Social Isolation

Social isolation is the absence of connectedness to people, community, and therefore, influence and power. It creates barriers to developing supportive relationships and communities, sharing personal and communal experiences, or forming part of the bigger whole that can build a sense of individual and collective identity.

The toll of social isolation has been shown in recent studies in which nearly 1 in 4 Wisconsinites report that they only sometimes or never get the social and emotional support they need. Only 4 in 10 American adults said that they feel very connected to others. Even more troubling, caregivers of children, especially mothers and single parents, are more likely to experience feelings of loneliness.

When we are socially isolated, our health becomes vulnerable to heart attacks, dementia, depression, and early death. Recent studies have compared its impact to smoking nearly a pack of cigarettes a day. Additionally, when caregivers are socially isolated, they are less likely to have the coping skills and relationships to support them when they become overloaded by stress. In these critical moments, children become vulnerable to neglect.

In 2023, U.S. Surgeon General released a national plan to fight against our country’s “loneliness epidemic.” He said the following about the stories he heard from Americans:

“People began to tell me they felt isolated, invisible, and insignificant. Even when they couldn’t put their finger on the word “lonely,” people of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds would tell me, ‘I have to shoulder all of life’s burdens by myself,’ or ‘if I disappear tomorrow, no one will even notice.’ It was a light bulb moment for me: social disconnection was far more common than I had realized.” – Dr. Vivek Murthy

With these troubling realities in the United States on my mind, I observed India, its people and their connections with great attention and curiosity. The journey that would ensue inspired many insights as to how we might improve our social connectedness here at home.

Social Connectedness through Neighbors, Worship, and… Traffic?

Every family trip to India begins in Ahmedabad, the city where my father-in-law grew up and where he met my mother-in-law after she and her family returned to their native India from her childhood in Tanzania. Ahmedabad has nearly 10 million residents, where the sounds of life in the markets and streets can be difficult to escape.

My father-in-law grew up in Delhi Darwaja, Ahmedabad’s oldest neighborhood. His mother lived there until she passed five years ago, and he has been returning to the neighborhood every year for the past twenty years.

While my father-in-law moved away from India fifty years ago, his annual visit still inspires neighbors to come out to greet him and our family. As has occurred through generations, the neighborhood flower seller and jeweler stop what they are doing to share the latest in their lives with us. The deep roots of the families that have lived in the neighborhood for generations can be felt in those moments as the connection with one another feels like only a couple days have passed, not years or decades.

When we seek refuge from the sensory overload of the city, we find it in the serenity of the Hutheesing Jain Temple. This year, however, we walked into a celebration of worship that brought multi-generational families and devotees to sing and pray together. On a busy Thursday, a community of Jains came to celebrate their belonging through their beliefs and connection to one another.

Initially I was frustrated by the celebration as it broke the silence of our quiet sanctuary, but then I witnessed the power of social connectedness and belonging as they held each other in their songs and prayer.

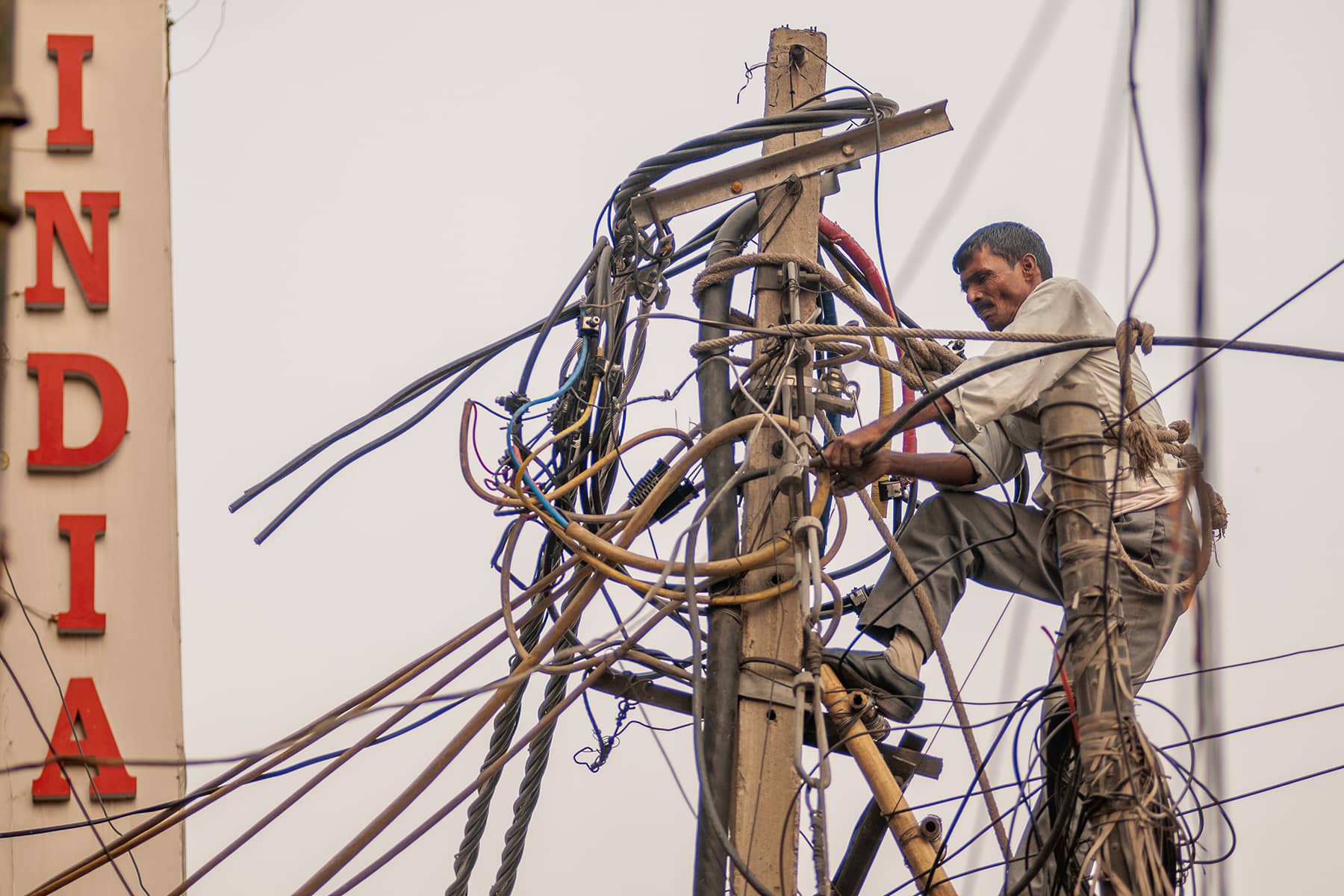

During our week in Ahmedabad, I witnessed another uniquely Indian expression of social connectedness. Traffic.

I have lived in Spain and Bolivia, and had traveled throughout the world, yet in all that time never experienced the overwhelming and confusing balance of intense, often hair-raising traffic and the endless tolerance and cooperation that makes it all work.

Coming from Milwaukee, it is easy to confuse the tireless symphony of car, rickshaw, motorcycle, and even bike horns as a sign of road rage. But once acclimated, I quickly grew to appreciate the communication that occurs in each of those horns. They are devoid of anger, and serve as a reminder that we all have somewhere to be and that we will get there more efficiently and safely if we honor each other’s needs.

Through the cooperation and social connection that occur in those short beeps that tell you “I am here,” the seemingly inevitable pileup becomes a fluid procession of big trucks to bike-drawn rickshaws. Over three weeks on the roads of India, I did not witness a single crash or road-rage incident.

The Anti-market Market

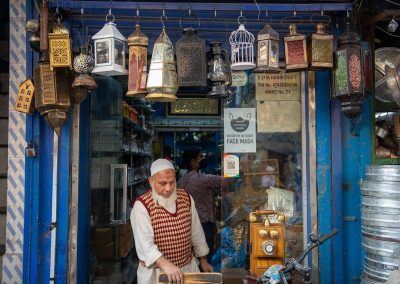

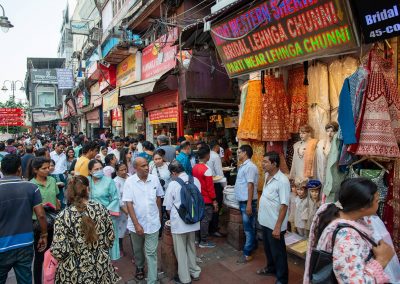

From Ahmedabad we traveled to New Delhi, India’s most populous metropolis with 30 million residents. We visited Old Delhi to explore the markets that were lined with vendors of everything from fresh fruits to piping hot chai and parathas, elegant saris to cheap and noisy toys, the latest tech gear to antique coins.

Commerce was at its finest as people buying and selling cycled through the crowded streets, and yet it felt different compared to our American understanding of the market. In India, if you want to buy a new phone, you go to the block of the market that is lined with one phone vendor after the next. If the vendor that you go to first does not have what you want, the vendor will go to the vendor next door to find it for you. Instead of the cutthroat competition that we are accustomed to, there is a sense of cooperation and community that recognizes that the favor will be returned.

The Art of Debate and Debating Art in the Himalayas

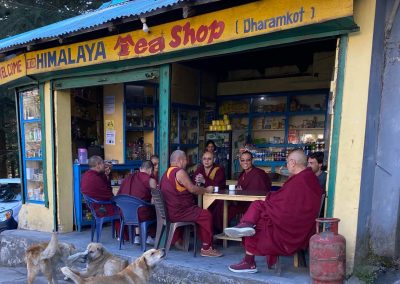

Our next stop was in the foothills of the Himalayas in Dharmsala, where we visited the Namgyal Monastery, the home of the Dalai Lama. The monastery is also home to two hundred monks who study Buddhist philosophy and elevate their understanding of the sacred teachings through debate.

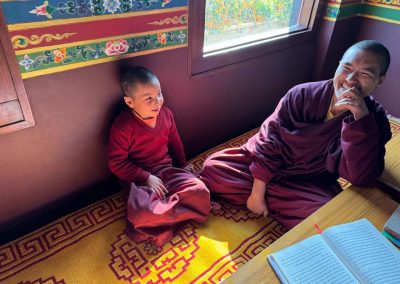

While exploring the monastery and the breathtaking Himalayan backdrop, I was pulled from my wonder by the sounds of dozens of children and their teachers engaged in lively debate. They were dressed in their traditional burgundy and yellow robes, a striking symbol of their belonging to the Buddhist community.

I was transfixed by how focused each young person was on the other’s point of view. As the debater stood making their argument, the listener sat before them. When interesting arguments were made, the listener would clap as a sign of approval. In these times of growing social isolation and political polarization, the listener’s active engagement and enthusiastic response was a sign of real connection.

“We humans are social beings. We come into the world as the result of others’ actions. We survive here in dependence on others. Whether we like it or not, there is hardly a moment of our lives when we do not benefit from others’ activities. For this reason it is hardly surprising that most of our happiness arises in the context of our relationships with others.” – The Dalai Lama

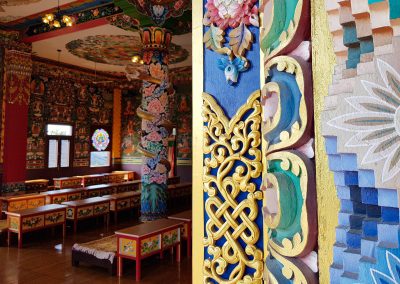

We next visited the Norbulingka Institute of Tibetan Culture, a community of Tibetan artisans trained in the ancestral knowledge of woodworking, painting, and embroidery. The Institute’s campus is a beautiful sanctuary with Japanese-inspired water gardens, rocky paths and vibrant plants, all nestled below the snow-capped Himalayas.

Upon entering the workshops, I discovered young artisans who were deeply immersed in their craft, or supporting one another by cleaning their tools. Each day, they sat with one another working on intricate pieces of art that often take months to complete and years to master. In that time together, they become family through their mentorship, struggles and accomplishments, and growth in their shared identity as artisans.

Social Connection through Service

Our next stop took us deep into my father-in-law’s family history upon returning to where his family lived before the Partition in 1947. Punjab, his family’s native province, was split into two, leaving one half as part of India, the other as part of Pakistan. It is also the province where Sikhism was founded and thrives today, especially at the Golden Temple in Amritsar.

The Golden Temple is an awe-inspiring place of worship that is surrounded by water and a compound of buildings of architectural beauty. Each day, thousands of people come to worship and to enjoy the solace and community meal known as langar.

At the Golden Temple, the community kitchen prepares and serves a hot meal to between 50,000 and 100,000 people regardless of one’s religion, ethnicity, caste, or socioeconomic status. The act of sitting together and breaking bread has been, for time immemorial, one of the greatest paths toward connection and understanding.

While the sight of hundreds of people sitting and eating together was inspirational, I found the act of service from the hundreds of volunteers who sat together peeling carrots and garlic, rolling and buttering rotis, and carrying gigantic pots of daal even more moving. I could see the light and joy in the faces of the volunteers as they laughed while working together to feed a community.

My fourteen-year-old son sat with the volunteers, where an older woman showed him how to butter rotis well while also doing it so quickly so that tens of thousands could be made and served throughout the day. In those moments, even amongst perfect strangers, it is impossible to feel alone in the world.

The Social Infrastructure of Connection

As I reflect now on the whole of my journey through India, I realize that social connectedness is often dependent on the places that bring us together. Places of worship, commerce, recreation, vocation, and even transit bring us together, many times around a shared purpose or identity. These places that hold community also create a sense of belonging for each individual in that community.

Over the past two years, I have been a part of dozens of community conversations with family-serving professionals and parents from across Wisconsin, and I heard the following when asked what may be causing the increased sense of loneliness and isolation.

People have less meaningful connections. Their trust and membership in religious groups, social clubs, and labor unions have been strained due to the increase in using smartphones, social media, remote work, and political polarization. Our social circles have shrunk due to the “Big Sort,” in which we have been divided by algorithms into narrow political, cultural, and social identities.

Beyond Milwaukee, communities are losing shared spaces like parks and pools, markets and malls, where social connection occurs – and losing jobs due to declines in industries such as farming, trades, and manufacturing.

Lower-wage earners are experiencing increased demands on their time and energy due to working longer hours and having less money to spend on transportation and social activities.

While the same has likely occurred at some level in India, the vibrant social infrastructure in their neighborhoods, places of worship, markets, and even traffic helps break through many of those micro-identities that empower people to find their shared identity or interests and build community.

The recent experience in India showed me a pathway that can be replicated in the United States – and here at home in Milwaukee, if we choose to again invest in our social infrastructure so that families can live, thrive, and build a supportive community for generations to come.

Overloaded: Understanding Neglect is a Milwaukee-based podcast series that aspires to build a shared understanding of neglect, its underlying root causes, and how they overload families with stress.

Luke Waldo

Ami Bedi

Pradeep Gaurs, Luciano Mortula, Mirko Kuzmanovic, Wan Kum Seong, Jeremy Richards, Daniel Prudek, Mohd Fauzie, Hari Mahidhar, Mark Stephens, Oliver Foerstner, Szefei, Oleg D., Neelsky, Photopan KPL, Travel Wild, Debora Van Der Haar, Jose Coso Zamarreno, Filip Jedraszak, Clicksabhi, Ispy Venus, and Phuntsokk (via Shutterstock)

Overloaded: Understanding Neglect is a Milwaukee-based podcast series that aspires to build a shared understanding of neglect, its underlying root causes, and how they overload families with stress.