As a South Side enclave gets restored, it serves as a model for quality living.

Six modest homes designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, widely regarded as the 20th century’s greatest architect, have put a Milwaukee South Side block on the map. Their international significance was evident to this writer when two young women visiting from Japan showed up, outside of visiting hours, with the hope of viewing a restored Wright bungalow.

Barbara Elsner, who was being interviewed at the time, graciously welcomed them and gave a brief tour of 2714 West Burnham Street. She noted of the visitors, “This happens all the time.”

Elsner has been a driving force in preserving Milwaukee’s row of American System-Built Homes, the only known example of an urban block with diverse Wright homes designed for middle-class families. Four of the six have been purchased by a nonprofit organization. One of two single-family cottages, known as Model B1, has been meticulously restored. Work on a duplex at 2732-34 West Burnham is currently underway, assisted by the second “Save America’s Treasures” grant that the National Parks Service awarded the preservation project.

Elsner has promoted awareness of the Wisconsin-born architect’s legacy for decades. She and her husband Robert lived in a Wright-designed home (the Bogk House) on the East Side from 1955 until recently moving to an apartment. Her late brother George Meyer wrote a successful grant that made the case that promoting Wright treasures could help draw tourists to Wisconsin. That has proven to be the reality, with individuals and groups, including from Europe, visiting Wright sites throughout the state.

In 1992, a 501(c)3 nonprofit called Lloyd Wright Wisconsin was formed with help from the Wisconsin Department of Tourism. One project was the Burnham Block.

“Key to our mission is education and historic preservation. We give full access to the Burnham Block historical site to any educational institution for use in their curriculum or programming. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Historic Preservation Institute took full advantage of the opportunity and used the Model B1 site as a classroom for students in a historic preservation studio–for an entire semester,” wrote board member and Burnham Block curator Michael Lilek in an eMail.

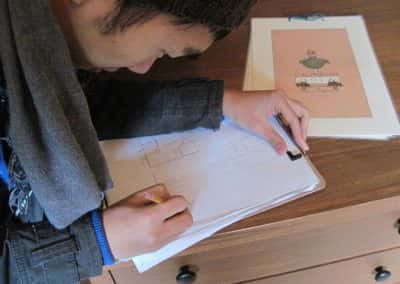

He said students learned historic preservation techniques through practical, hands-on learning. Students and faculty tested, measured, and documented the home, created a Historic Structures Report, and developed other critical research to guide the restoration. One faculty member even lived on site.

“It was great to work with the UWM Preservation Institute, and we hope they will do it again with the next building,” noted Lilek.

The Institute is hosting a lecture and celebration on November 16 as part of the Burnham block’s 100th anniversary.

Affordable Architect-designed Homes

Although Wright designed many homes for wealthy clients, including in the Chicago suburbs of Oak Park and River Forest, he also focused on interpreting his design ideas into more affordable dwellings.

In the January 1938 issue of Architectural Forum, Wright commented, “I would rather solve the small house problem than build anything else I can think of.”

On the Wright in Wisconsin website Lilek stated, “Indeed, among Wright’s greatest masterpieces are several small homes designed for clients who could afford little. Many of these residences owe their existence to some form of client labor (do-it-yourself), ingenious cost-cutting or salvaging. Each magically shelters it occupants in beautiful spaces, connects them to nature, and allows them to feel more alive.”

Wright created 960 drawings and sketches for the American System-Built Homes project between 1915 and 1917, after partnering with prominent Milwaukee developer Arthur L. Richards. Their line included 36 different models with multiple options, including roofline variations.

Model B1, the Burnham bungalow open for tours, maximizes every inch of an 805-square-foot-floor plan. Natural light shines through 33 windows, many located high up for privacy. They make the house feel bigger. Flexible spaces include a breakfast nook, an ample hallway, and a living room that includes a table and chairs for dining or other uses. Built-in furniture, doors and architectural trim are made of redwood, which was then affordable. Elsner pointed to innovative space savers and design that cost less while producing big impacts, such as continuous banks of windows, rather than numerous individual ones. She said the modest homes provided “quality living in a city environment.”

In 1915 Richards contracted with Wright to promote the line of homes. Covering all parts of the United States, Canada and Europe, their agreement called for the Richards Company “to furnish, as far as possible, all materials entering into the construction of the buildings and to at least furnish the plans, drawings, specifications and details and lumber, millwork, exterior plaster material, paints, stains, glazing, hardware trimmings and electric lighting fixtures for said buildings.”

Richards committed to developing a distribution channel of builders and developers. Lilek noted that Richards “appears to have focused his efforts in the Chicago area and a few other Midwestern cities.”

A dramatic ad in the July 18, 1917 Chicago Tribune proclaimed: “You Can Own and American Home.”

Nevertheless, the partnership and ambitious enterprise soon dissolved. The six homes on Burnham are the only known ones developed as an enclave. Fewer than 20 other ASBH homes were built in scattered locations throughout the Midwest.

Lilek described the Burnham Street structures as “four two-story flat-roofed stucco-clad duplexes, and two one-story cottages of different designs. All of the homes have been altered. Most noticeable is the addition of pre-cast stone, a porch enclosure, and metal-tile roofing at 1835 S. Layton Blvd. Less evident are interior alterations and the replacement of all exterior surfaces.”

One duplex was restored and converted into a single-family home by Jillayne and Dave Arena, who lived there for about 30 years. Elsner says the couple helped to promote awareness of the Wright homes on Burnham and their significance. The Arenas, who sold the home after moving out of state for work, will be honored at the anniversary celebration. New owners lease it as a vacation rental property.

Elsner said several factors probably influenced the demise of the ASBH project. The entry of the United States into World War I on April 6, 1917, diverted building materials to wartime needs, which stalled housing starts. Elsner also noted that around the time Wright began focusing on the design and construction of Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel, one of his master works. Wright successfully sued Richards over contract disputes, effectively killing the project, although they later reportedly rekindled a cordial rapport.

The Burnham Street Development

When the Wright homes were built, Elsner said Burnham Street to the west of Layton Boulevard was “celery fields” at the edge of town.

“The location is also noteworthy because it was very near the now-abandoned Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Company’s interurban and city streetcar rail lines, which were extended to the spot in 1905. By 1907, area residents could take the ‘City Service’ line east from what is now 31st Street and Burnham Street to anywhere in the city, and they could travel west by interurban to West Allis, Hales Corners, Waukesha, East Troy, and to other points. In terms of city development and transportation, the site was ideally located,” wrote Lilek.

The nonprofit Frank Lloyd Wright Wisconsin program actively fundraises for ongoing restoration projects, with the goal of restoring all of the homes it owns and eventually opening an education and visitor center.

Anniversary Celebration

A free public event to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the construction of American System-Built Homes will be held Wednesday, November 16, from 5:30 to 9:00 pm at the offices of Zimmerman Architectural Studios, 2122 West Mount Vernon Avenue in Milwaukee. It will include a presentation about the history of the ASBH homes, a silent auction, and a display about other Wright buildings in city.

House Tours:

Eleven Frank Lloyd Wright sites statewide, including a church, homes, community centers, corporate buildings, and Wright’s Taliesin Estate in Spring Green, can now be toured regularly.

The Burnham Homes are open for paid, docent-led tours without appointment the second and fourth Saturday of each month (excluding major holidays). A Wright and Like annual tour features Wisconsin private and public buildings in various cities, and is next scheduled on June 3, 2017 in Milwaukee.