It is easy to miss signs of progress in race relations when perennial headlines overwhelmingly lament Milwaukee as being the most segregated city in America. But there is a small success story that has gone completely under the radar, mostly because it has happened organically and is not a result of organized civic mandates. It also involves a subject for which the general public has traditionally lacked a deep understanding.

What achieved this bridge between the racial gulfs in Milwaukee was the exposure over the past decade to a foreign pop culture phenomenon called Anime. The result of this interracial acceptance and engagement was vividly on display at the Anime Milwaukee (AMKE) event held March 11 to 13 at the Hyatt Regency & Wisconsin Center.

In its ninth year, the annual convention and largest of its kind in Wisconsin, showed how Anime has become a cultural connector for all of Milwaukee’s ethnic youth. By its nature, Anime has no cultural boundaries. It is not merely an entertainment choice associated with kids of racial privilege.

Antwan Lackey is an example of how Anime has found a way to erode long entrenched social barriers. As an African-American millennial who lives in Milwaukee’s Northside, he brought his two children to Anime Milwaukee to celebrate the Japanese import that first captured his imagination.

“I love Anime. It’s a lot different than the American cartoons we grew up with as kids. There are so many types of stories, and the characters all have such depth and development in the series,” said Lackey. “Anime is for everybody. It isn’t exclusively directed towards one ethnicity. It is so open, so universal, anyone can get into it, enjoy it, and just fall in love with it.”

Anime is the abbreviated pronunciation of animation in Japanese, and refers to that nation’s particular style of hand-drawn cartoon. Figures typically have overly large eyes, which originated from helping Japanese audiences to better understand the characters emotions. In Japanese culture, the eyes are where a person would be looking for emotional cues.

America adopted Anime decades ago, beginning with shows like Speed Racer in the late 1960s, but originally only appealed to a narrow subculture of science fiction enthusiasts. However in recent years, with cable channels such as the Cartoon Network, streaming services like Crunchyroll, and video games based on Anime series, this form of Japanese entertainment has reached a more mainstream audience.

“It has a message, and I like that a lot. Its got a feeling and more emotion,” said Brandi Byas. “Anime is love. Anime is life.”

Cultural saturation has helped changed the stereotype of Anime fans in America from predominately white male youth to virtually everyone.

“People find Anime Milwaukee a safe place to come out of their shells and meet like-minded people, develop more friendships, and socialize in what may otherwise be a more difficult or less comfortable environment,” said AMKE’s media director, Vic Walter. “We are seeing this trend at other conventions around the United States. I’d like to say that it’s due to the overall growth and spread of Anime and Anime-focused conventions, because they are a accepting place for fans.”

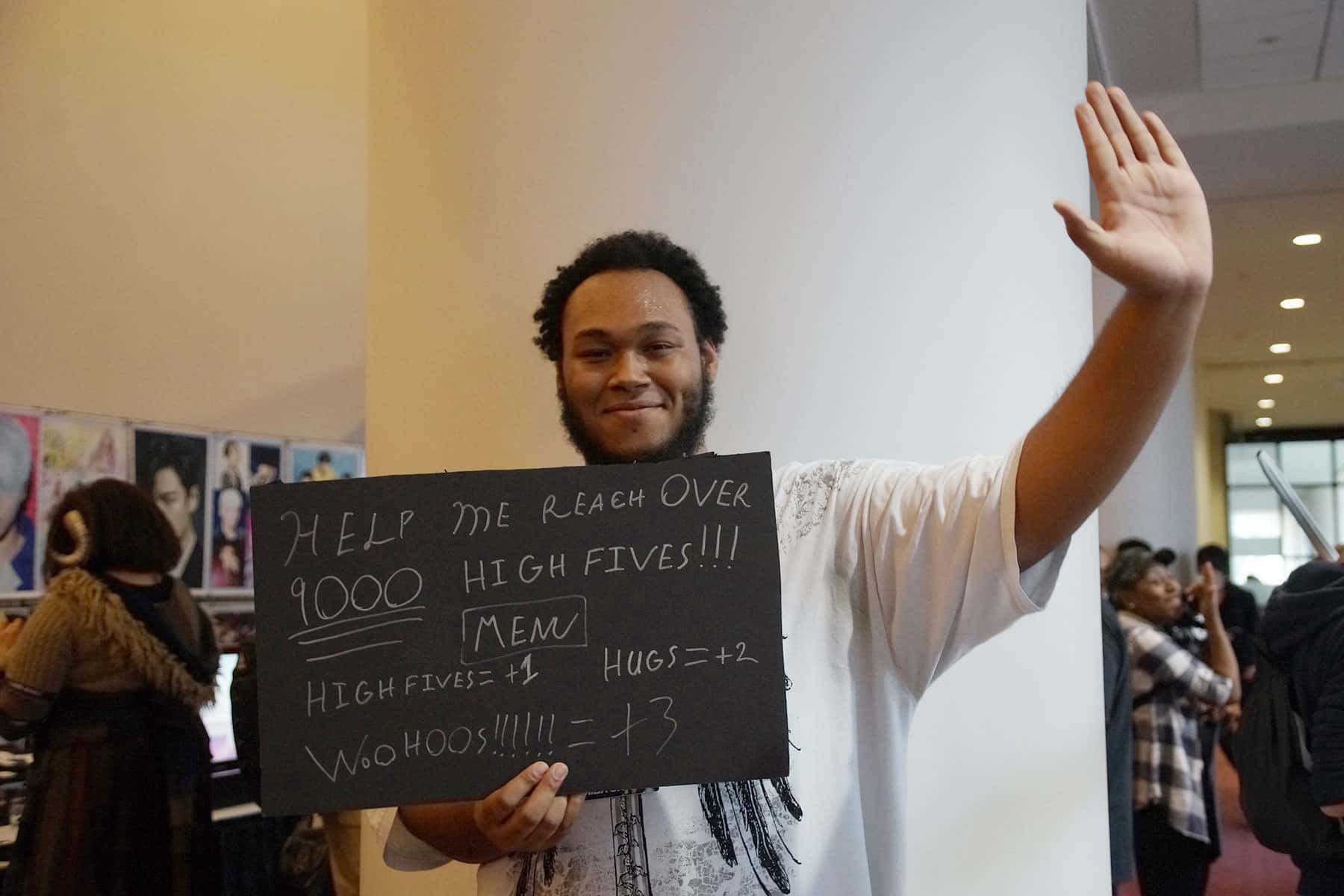

Anime Milwaukee 2016 proved how wrong the old assumptions are about fan stereotypes. The convention was an open venue that stimulated interracial exchanges in ways that countless tax-payer programs have failed to accomplish.

“I didn’t expect to see so many black people here at Anime Milwaukee,” said Cedric Jasber. “Growing up outside of Madison, there is a big crowd for Anime but you’d never think it is as diversified as it is here. Anime is an amazing way for all different races and all different cultures to just come together. It is one thing we can all get along under.”

In Japan, Anime appeals to enthusiasts of every age and gender, because it offers a broad range of genres. Literally something for everyone, the spectrum of stories include: action-adventure, business and commerce, comedy, detective, historical drama, horror, mystery, romance, science fiction and fantasy, sexuality, sports and games, and suspense.

“Its a great distraction. You can learn a lot of things from it. Not only about the culture from where it comes from. But also they teach lessons like being open minded, a constant through all Anime. Being open minded and consequences for being evil are reoccurring themes. Anime’s influence changed my character from watching so much of it. I feel it is more positive, even the ones that make you almost cry,” said Eric Kyle, another African-American Millennial from the Northwest side of Milwaukee.

While the Anime Milwaukee convention does not collect statistical data about those who attend, walking around the convention provided empirical confirmation of how Anime speaks to multi-generational and multi-cultural people. Anime itself will not solve the very real problems faced by disadvantaged residents in Milwaukee. But unlike the adversarial escapism offered by sports teams and the nature of competitive games, the appeal of Anime is with its positive messages. Where as sports is an unrealistic role model for struggling youth, for the most part Anime offers socially beneficial and moral examples.

Community leaders should consider how Anime speaks to Milwaukee’s youth and influences their lives in such places as 60th Street and Silver Spring Road. Perhaps more venues and programs that embrace Anime would that help incubate this positive trend.

“One of the big attractions of Anime for me was Dragon Ball Z, because I’ve always been into martial arts,” said Lackey. “And what that goes to show you is, help each other. Don’t fight each other. Defend each other. Work together as a team. Don’t go out looking for a fight. Lend a hand. Grow together, be a friend and not an enemy.”

Attendance this year at Anime Milwaukee was significantly higher than 2015 with more than 9,300 visitors, and a projected impact for the downtown economy of 2.2 million dollars.