A travelogue of a Milwaukee woman’s trek to the Dakota Access Pipeline protest that highlights Native American injustices and environmental concerns.

There are important issues that cross into the awareness of our busy lives, things we feel strongly about but for many reasons are unable to support with action. Amy Thomas is not an activist, but was moved to visit the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) protest as a silent witness. With her two young sons, Thomas made the 1,500 mile round trip from Milwaukee and has this experience to share.

I was browsing through Facebook one day in the middle of August, when the situation in Cannon Ball, North Dakota caught my eye. I read through the article and looked for more, wanting to know all I could about this thing called, DAPL, or the Dakota Access Pipeline.

I learned that it is a 1,200 mile pipeline that would carry just under a half a million barrels of oil across three states. This is nothing new for America, there are numerous pipelines stretched across the country in every direction. What makes this pipeline significant is that it was planned to go through Native American burial grounds and right above the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. These people are one of the poorest groups of Native American people and they depend greatly on their water for farming and raising cattle.

Over the next two weeks I felt the need to explore the subject further. That was then when I came across a social media post calling for peaceful witnesses. Residents of the camp were asking the public to come to the camp and witness first hand the shared love and prayers of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, then to go back out into the world and share the experience with others.

I thought about the opportunity, and wondered how I could make it happen. My family had just returned from a week-long vacation in Colorado and the new school year was due to start for my children in a matter of days. My husband and I are also both educators, and he had already returned to work. This left me with two children to look after and no one to entrust their care to if I went away on my own for a few days.

After much deliberation and consideration, I decided to make the journey and bring my boys along on the adventure. I left Milwaukee on September 9 with two children in tow, my ten year-old son and my fifteen-year-old son, who has physical and cognitive disabilities. There was $430 in my wallet and 811 miles between us and our destination. We left around 5:00 pm and I drove as far as I was able until I struggled to stay awake. I pulled over finally at a rest area in North Dakota and slept for a few hours. I woke early the next morning and hit the road. I was determined to arrive at camp at a decent hour to allow myself, and my children, time to set up camp and make ourselves comfortable.

When I arrived in Bismarck my anticipation soared. I made a turn down Highway 6 in Mandan and drove to the camp. As previously warned, I found myself at a police checkpoint. Three police officers approached my vehicle, walked around it, looked in the windows, at our belongings, at my children. They asked where I was going. I answered honestly about my purpose for being there. They explained that the road was not open to visitors and that I would need to take a different route, which consisted of a maze of gravel backroads. They were gracious enough to give me a map, but it ultimately did me little good. Forty-five minutes later I found my way past a casino and a few miles after that, a small gas station. Luckily there was a large wooden sign posted across the street that said CAMP and pointed us in the correct direction.

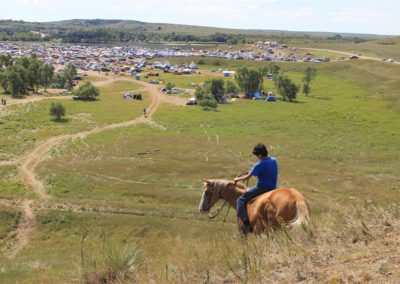

Coming around that corner, where the camp is first visible, was a breathtaking site. This was not due to the majestic and beautiful view, but knowing what the camp stood for and what it held for the world to see.

Entrance to the camp was much like entering any organized function, like a concert or sporting event. With so much traffic, they had to manage the flow of people and direct them to where they needed to where to go. The size of the camp was overwhelming. I selected a spot close enough to the port-a-potties that I would not have to worry about my boys walking a long way in the dark. It was also just a short distance across from the main road to where everything was set up. There was a kitchen, council gathering tents, and a large fire where people gathered to speak, sing, and pray.

We were greeted almost immediately by a kind Native American man, Frank Archambault, who had been at camp for months and knew all there was to know about it. He explained where we could go for food, first aid, water, and warned us of spiders. That part I will never forget, because it scared the boys enough to sleep in the car that night.

We introduced ourselves to our neighbors, who welcomed us, offered food and fire if needed. One of them in particular had a dog, which the boys loved. They offered to walk her and she was overjoyed.

I left the boys to explore while I went to listen to the elders speak. They talked about the treaties, both past and present. The community leaders explained about their tribal differences, which led to disagreements and kept them from communicating with one another for years. It was not until the pipeline crisis that they were able to come together in prayers, love, and tears.

Drummers had traveled all the way from California and sang while we all watched quietly in awe. At the end of the performance we all formed a line and thanked them each with a hand shake and a warm smile. I left there feeling a deep sense of peace. I believed that if we all came together we could stop the dreaded pipeline.

I took my time walking back to our camp spot. I explored and took it all in. It was hard to reconcile what I saw against the news reports. This was the place that people said had violent protesters? It could not possibly be. There must have been somewhere within this camp where those violent Native Americans were hiding. I never did find them. And, I tried. I explored every last inch of that camp, with and without my two boys. If I failed to investigate an area, the boys covered it on their own. I never felt the need to stay with them, to watch over them. I would join the elders at the fire and listen, while the boys walked around and gawked at the large teepees, or teased the horses.

While staying at the camp it was made clear that we should each do our part to make sure it ran smoothly. The boys and I decided we would help refill the water jugs used for cooking. It was a chore that we could all do and work on together. The boys wanted to help cut potatoes, but by the time we made it there they had moved on to cutting up a chicken, and none of us wanted to volunteer for that duty.

Not knowing what to expect when we arrived, we packed our own food in advance. We had a cooler full of quick meals and snacks. One morning, we decided to join the line for breakfast. I had been in the camp kitchen earlier, which consisted of tables and shelves covered by an industrial tent, and became aware of all the options in we had to eat. That morning I choose the fried bread and a large coffee, my boys choose oatmeal and granola bars with orange juice and milk. We were reminded numerous times that we should never be hungry while at camp, and never to hesitate to come get something, even if between scheduled meals.

I was told that this is the largest gathering of Native American nations in over 150 years. Over 300 nations, and 7,000 people had entered the camp to show their support. Along the main road in camp could be seen all of the flags from different groups supporting the Standing Rock Sioux and their cause. There were actually more flags there than in the United Nations. It was an impressive sight.

The mothers and educators of the camp organized a small homeschool for the children during the week. They learn indigenous languages from across the nation, drumming, and the traditional lessons in math and reading. The school varied in ages and skill ability, yet I felt the differences were not important. The students and teachers all worked together and it was an equal amount of give and take.

When it came time for us to return to Milwaukee I felt a great sadness, as if my time and purpose in Standing Rock was not yet completed. I felt guilty because I could leave. The situation there was not a part my daily life or reality. I would not have to worry about the upcoming winter months and keeping my children warm. I would not have to worry about a pipeline carrying 450,000 barrels a day across the land I depend on for my livelihood. Although that point is an issue most Americans could relate to if they thought about. The Dakota Access Pipeline would go directly below a river which connects to the Missouri River, a historic waterway that spans the length of the United States. An oil spill would potentially pollute the drinking water for millions of Americans, including my own family at home in Milwaukee. The problem may seem far away, and not a local concern. But it is closer than my neighbors and co-workers realize.

When I did finally arrive home I fell into my husband’s arms and cried. I cried for days. Although my experience at camp was peace and filled with a sense of oneness, I felt so emotionally drained. When I left, the battle was just beginning for the water protectors in North Dakota. The situation there is not expected to get easier over time.

I answered a call to come to the camp and attest to its peaceful ways. I can testify to this and will. I felt as if I had been among family, everyone watched out and helped each another. There was nothing to give me, or my children, any reason to think differently. My children were able to gain insight to something no one else at their schools have seen, and many are not even aware of. They are better people for this transformative experience, and they already long to share their stories with others.

The trip enlightened me to many conditions I had not been previously exposed to. One issue that really hits home, as a resident of Wisconsin, is the similarities between Standing Rock Reservation and the inner city of Milwaukee. Like Standing Rock, Milwaukee has a large population of low income residents living in a small area. Both environments only provide opportunities to sustain a minimal way of life and not really thrive. A civil society cannot allow resources to be taken away from the poorest communities in America without accountability. As I saw in Standing Rock, if members of our community all come together to make a difference, positive change can happen. We must have these conversations, and continue them for many weeks, months and years to come.

In the time that I have been home since the trip, I have attempted to adjust back into my reality of life in Milwaukee. It has not been easy. I still feel a calling to return to camp. I hope to visit it again soon, before the winter comes. In the meantime, as a mother, an educator, and a newly minted activist, I will use my knowledge and experience to share with the people of my hometown. Many of the lessons I learned in North Dakota about community can be applied to Milwaukee, and the needs we have here.

Joint Statement Regarding Standing Rock Sioux Tribe v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers:

The Department of Justice, the Department of the Army and the Department of the Interior issued the following statement regarding Standing Rock Sioux Tribe v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

“We appreciate the District Court’s opinion on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act. However, important issues raised by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and other tribal nations and their members regarding the Dakota Access pipeline specifically, and pipeline-related decision-making generally, remain. Therefore, the Department of the Army, the Department of Justice, and the Department of the Interior will take the following steps.

The Army will not authorize constructing the Dakota Access pipeline on Corps land bordering or under Lake Oahe until it can determine whether it will need to reconsider any of its previous decisions regarding the Lake Oahe site under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) or other federal laws. Therefore, construction of the pipeline on Army Corps land bordering or under Lake Oahe will not go forward at this time. The Army will move expeditiously to make this determination, as everyone involved — including the pipeline company and its workers — deserves a clear and timely resolution. In the interim, we request that the pipeline company voluntarily pause all construction activity within 20 miles east or west of Lake Oahe.

“Furthermore, this case has highlighted the need for a serious discussion on whether there should be nationwide reform with respect to considering tribes’ views on these types of infrastructure projects. Therefore, this fall, we will invite tribes to formal, government-to-government consultations on two questions: (1) within the existing statutory framework, what should the federal government do to better ensure meaningful tribal input into infrastructure-related reviews and decisions and the protection of tribal lands, resources, and treaty rights; and (2) should new legislation be proposed to Congress to alter that statutory framework and promote those goals.

“Finally, we fully support the rights of all Americans to assemble and speak freely. We urge everyone involved in protest or pipeline activities to adhere to the principles of nonviolence. Of course, anyone who commits violent or destructive acts may face criminal sanctions from federal, tribal, state, or local authorities. The Departments of Justice and the Interior will continue to deploy resources to North Dakota to help state, local, and tribal authorities, and the communities they serve, better communicate, defuse tensions, support peaceful protest, and maintain public safety.

“In recent days, we have seen thousands of demonstrators come together peacefully, with support from scores of sovereign tribal governments, to exercise their First Amendment rights and to voice heartfelt concerns about the environment and historic, sacred sites. It is now incumbent on all of us to develop a path forward that serves the broadest public interest.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Amy Thomas

Amy Thomas is a relatively new resident of Milwaukee and a married mother of three children. She works for the Shorewood School District in the Special Education department, and is the co-founder of Team Awesome, the first inclusive technical theater program in the United States. She is a self-proclaimed hippie, an advocate for human rights, animal rights, and environmental awareness.