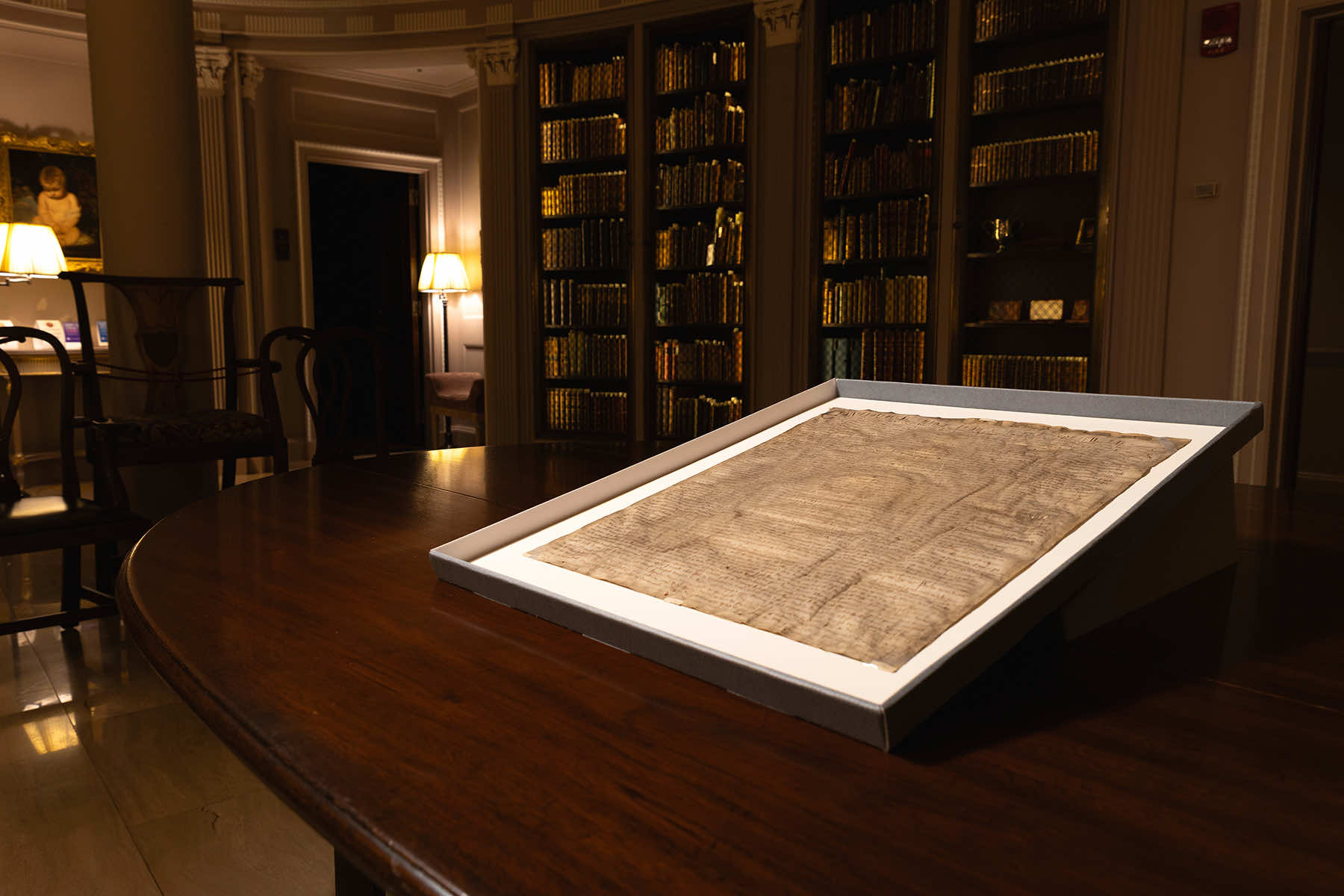

For decades, a tattered and misdated parchment sat largely unnoticed in the Harvard Law School Library’s archives.

Purchased in 1946 for just $27.50, it was presumed to be an unremarkable 14th-century reproduction of the Magna Carta, a historic but common reference text. That presumption was upended when two British scholars examined the document in late 2023. They concluded it is an original version of the Magna Carta issued in 1300 by King Edward I.

“My reaction was one of amazement and, in a way, awe that I should have managed to find a previously unknown Magna Carta,” said David Carpenter, a professor of medieval history at King’s College London. He was searching the Harvard Law School Library website in December 2023 when he found the digitized document. “First, I’d found one of the most rare documents and most significant documents in world constitutional history. But secondly, of course, it was astonishment that Harvard had been sitting on it for all these years without realizing what it was.”

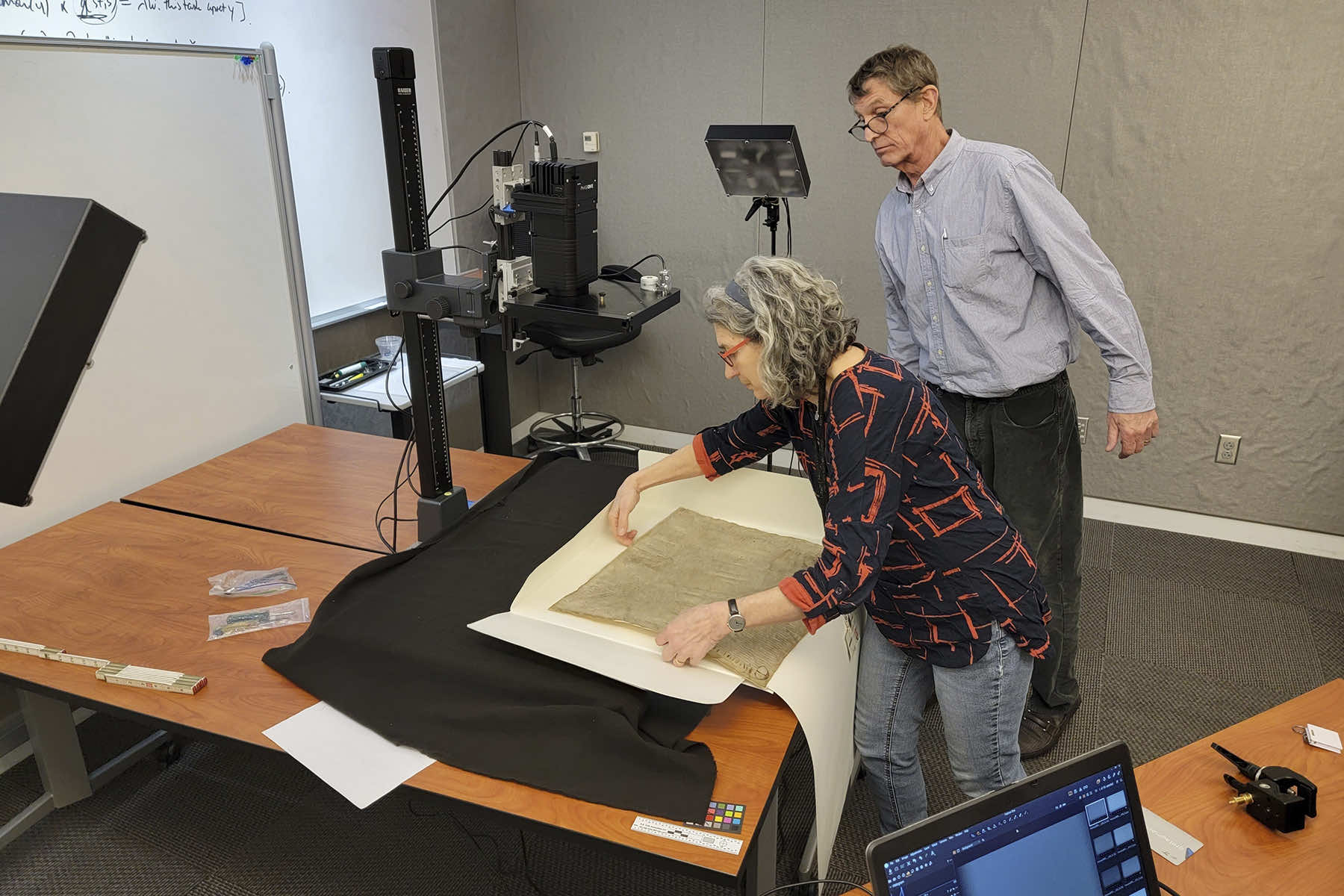

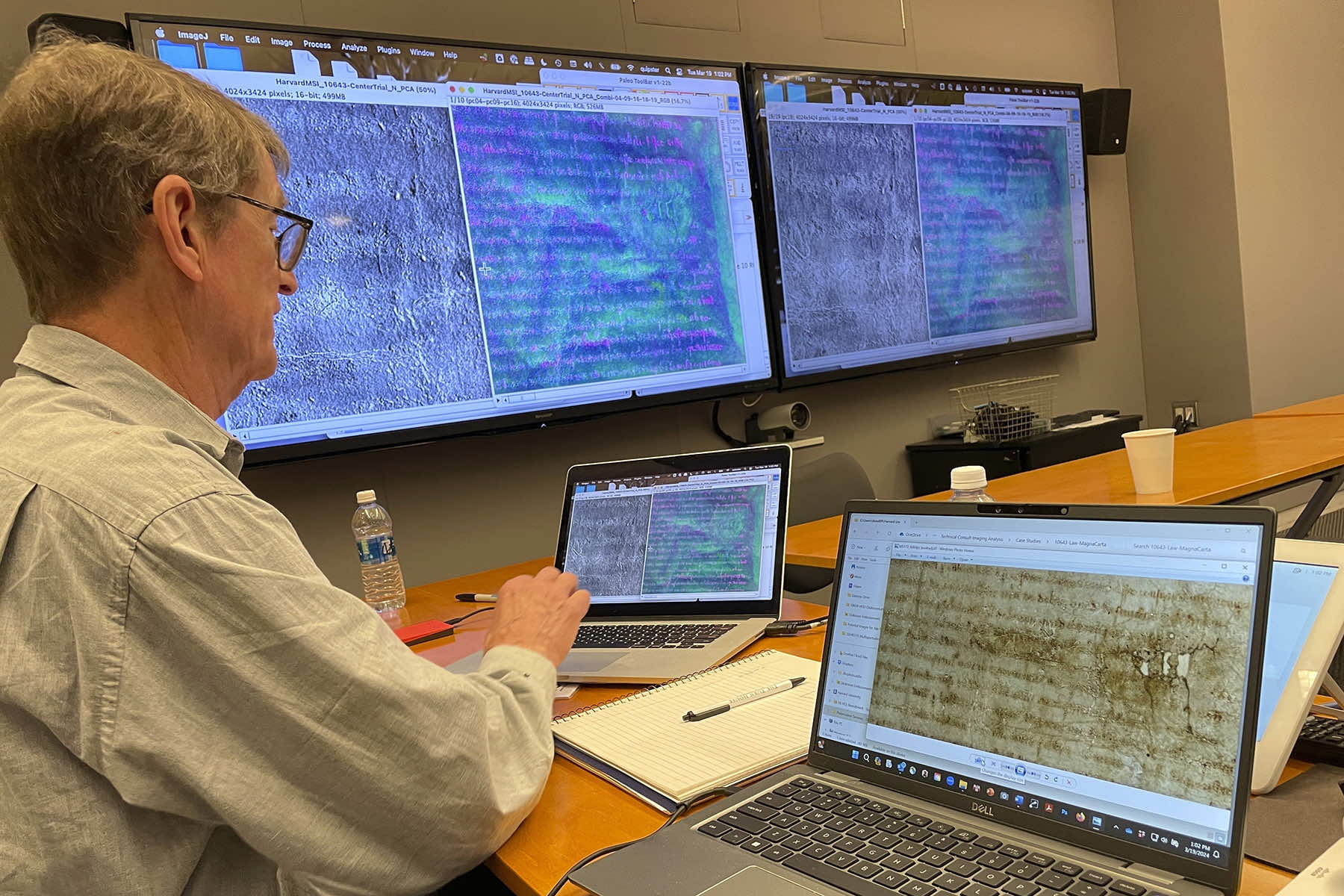

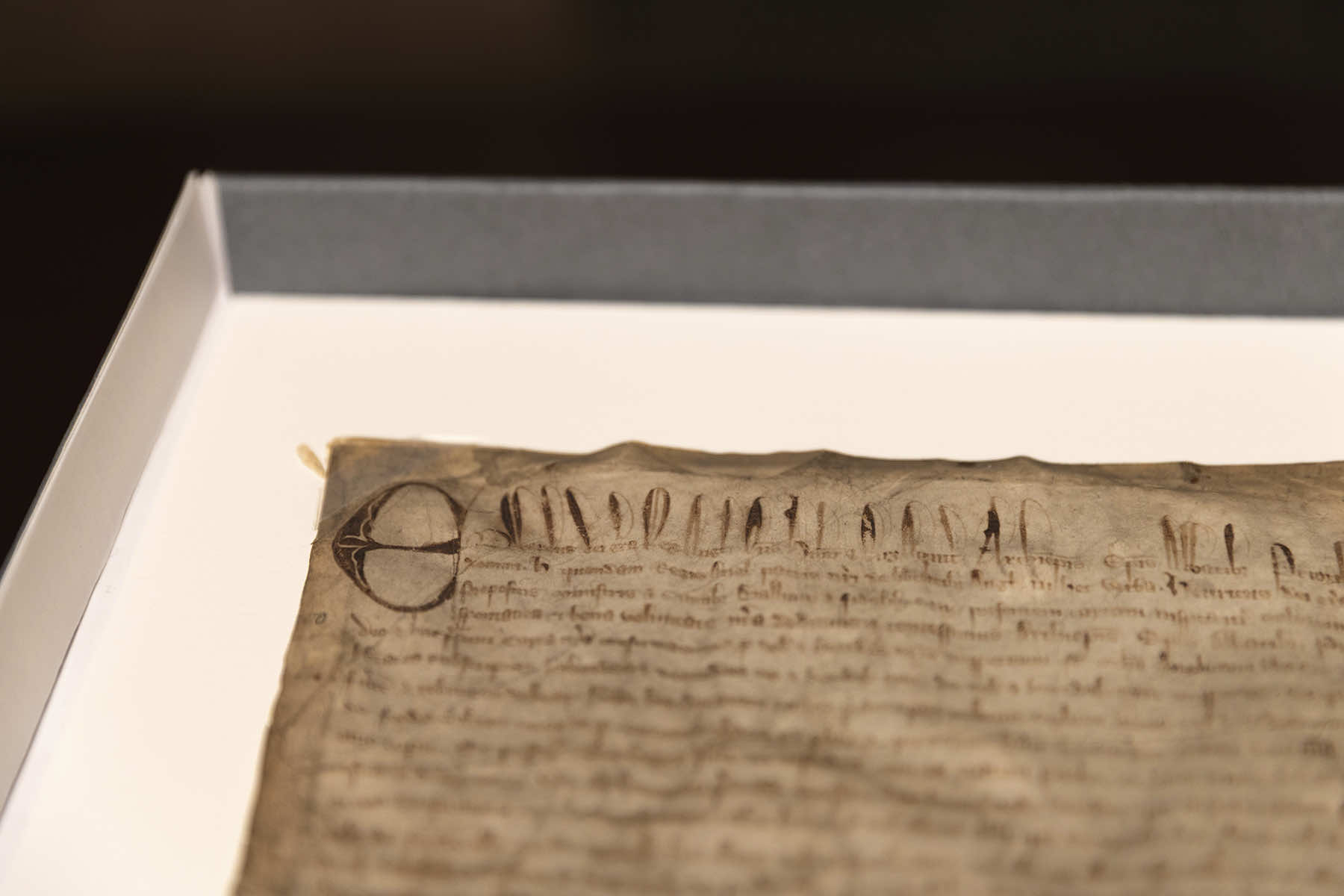

Carpenter partnered with Nicholas Vincent of the University of East Anglia to authenticate the document. Through spectral imaging and ultraviolet scans of the faded manuscript, the researchers confirmed both textual and stylistic elements, such as the large capital “E” in “Edwardus,” matched known copies of the 1300 edition.

Harvard’s Magna Carta became only the seventh known copy from that year, a critical version that marked the last time the document was fully reissued and sealed by a reigning English monarch.

The artifact is now estimated to be worth millions. A similar 1297 copy sold at auction in 2007 for $21.3 million. Yet Harvard, which never intended to sell the piece, finds its significance lies far beyond its monetary value.

“We think of law libraries as places where people can come and understand the underpinnings of democracy,” said Amanda Watson, the assistant dean for library and information services at Harvard Law School. “To think that Magna Carta could inspire new generations of people to think about individual liberty and what that means and what self-governance means is very exciting.”

That constitutional legacy traces back to a fateful day more than seven centuries ago. On June 15, 1215, in a meadow at Runnymede, King John of England, under pressure from armed barons rebelling against his heavy-handed taxation and autocratic rule, agreed to a document with 63 clauses.

While many provisions addressed feudal customs and local justice, some reached far beyond medieval grievances. The Magna Carta introduced foundational legal principles that endure today, including protections against unlawful imprisonment and the right to a fair trial.

It famously proclaimed, “No free man shall be seized, imprisoned, dispossessed, outlawed, exiled or ruined in any way, nor in any way proceeded against, except by the lawful judgement of his peers and the law of the land.” It also provided that “To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice.”

Though King John had the charter annulled by the pope within weeks, its ideas sparked continued resistance. When the king died the next year, the Magna Carta was reissued and confirmed under the reign of his successors, eventually becoming codified English law. By 1300, under Edward I, the full document was set out for what would be the final time with the king’s seal, a version now confirmed to be a part of Harvard’s archive.

Vincent determined the document was sent to a British auction house in 1945 by a World War I flying ace who also played a role defending Malta in World War II. The war hero, Forster Maynard, inherited the archives from Thomas and John Clarkson, who were leading campaigners against the slave trade. One of them, Thomas Clarkson, became friends with William Lowther, hereditary lord of the manor of Appleby, and he possibly gave it to Clarkson.

“There’s a chain of connection there, as it were, a smoking gun, but there isn’t any clear proof as yet that this is the Appleby Magna Carta. But it seems to me very likely that it is,” Vincent said. He said he would like to find a letter or other documentation showing the Magna Carta was given to Thomas Clarkson.

While the academic tracing of provenance continues, so too does reflection on the Magna Carta’s role in shaping American constitutionalism.

In the early 1600s, King James I and King Charles I both reasserted the power of the king. Jurist Sir Edward Coke used the Magna Carta to insist that longstanding English customs guaranteed liberties to British subjects and required the king to comply with the law.

There were limits to a king’s power to tax his subjects and his power to punish them. This legal struggle was unfolding just as British subjects were colonizing the North American continent, and the charters of the new colonies echoed Coke’s arguments.

The 1629 charter of the Massachusetts Bay Company, for example, established that colonists and, crucially, the children they might have in the colony, “shall have and enjoy all liberties and ommunities of free and natural subjects.”

As constitutional scholar Mary S. Bilder noted, lawyers and political figures put into the documents of the early British settlement of North America the belief that liberties were the birthright of English subjects.

That belief informed colonists’ opposition to the 1765 Stamp Act, which imposed a new tax to which they had not given their consent and called for those who violated the law to be tried not by a jury of their peers but rather in admiralty courts.

The Massachusetts Assembly declared the Stamp Act to be “against the Magna Carta and the natural rights of Englishmen, and therefore, according to Lord Coke, null and void.”

British politician William Pitt told Parliament, “The Americans are the sons, not the bastards, of England.”

In September 1774, as tensions between the king and the colonists intensified, the first Continental Congress met in Philadelphia and wrote a declaration of rights and grievances, claiming the liberties guaranteed by “the principles of the English constitution, and the several charters or compacts.”

Showing the unity of the colonies, the Congress published an image of 12 arms holding a column crowned by a liberty cap and resting on the words “Magna Carta.”

The colonists threw off the monarchy to establish a government based on the idea that all people must answer to the law in 1776.

As Thomas Paine wrote in Common Sense, “In America, the law is king. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be king; and there ought to be no other.”

The new states were writing their own constitutions that defended their liberties, including their protection from loss of life, liberty, or property without due process of the law. That concept went directly into the first ten amendments to the Constitution, known collectively as the Bill of Rights.

The Fifth Amendment provided that no “person shall be … deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

In 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment applied that principle to the states as well as the federal government by saying, “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law, nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

In modern times, the Magna Carta remains more than a historic artifact. It is a mirror for the evolving relationship between individual rights and governmental power. That reflection has become particularly charged amid current debates over the rule of law and civil liberties in the United States.

During an interview aired May 4, Donald J. Trump was asked whether individuals in the U.S. have a right to due process.

He responded, “I don’t know,” even after NBC’s Kristen Welker reminded him that the Fifth Amendment enshrines that right. “It seems, it might say that, but if you’re talking about that, then we’d have to have a million or two million or three million trials,” he added, casting doubt on a foundational principle that originated with the Magna Carta itself.

The rediscovery of Harvard’s 1300 Magna Carta arrived at a moment fraught with constitutional tension. Vincent noted the symbolic irony.

“It turns up at Harvard at precisely the moment where Harvard is under attack as a private institution by a state authority that seems to want to tell Harvard what to do,” Vincent said.

Musician Bruce Springsteen struck a similar note while performing in Manchester, England, just days before the document’s authentication was announced in May.

“In America, the richest men [are]… abandoning our great allies and siding with dictators against those struggling for their freedom. They’re defunding American universities that won’t bow down to their ideological demands. They’re removing residents off American streets and, without due process of law, are deporting them to foreign detention centers and prisons. This is all happening now.”

He also criticized lawmakers who have “no … idea of what it means to be deeply American.”

Despite his criticism, Springsteen offered a message of perseverance by saying, “The America that I’ve sung to you about for 50 years is real and, regardless of its faults, is a great country with a great people, so will survive this moment.”

That message may find added strength in the rediscovered charter. Though written on parchment and born of feudal conflict, the Magna Carta continues to echo across centuries and borders. Its clauses were crafted by barons seeking to check the power of a single man.

In doing so, they created a framework that would inspire generations to demand fairness, legality, and accountability in governance. Its survival, from the meadows of Runnymede to a Harvard archive mislabeled and nearly forgotten, underscores the durability of those ideas.

What began as a negotiated peace between a king and his rebellious nobles ultimately seeded the idea that no leader, however powerful, is above the law.

Now, with its legacy reaffirmed and its presence in the U.S. once again visible, Harvard’s Magna Carta offers more than a historical curiosity. It reclaims its role as a living symbol in an ongoing struggle to define liberty and justice.

“It is priceless,” said Carpenter of the newly authenticated artifact. And, in a time of deep legal and political questions, it is more urgently relevant than ever.

© Photo

R.B. Toth (AP), Lorin Granger (AP), Debora Mayer (AP)