Playing as a pitcher, Biddle said he earned the wordy nickname “The Man Who Beat the Man Who Beat the Man” for a victory his first season over Lefty McKinnis, one of the few pitchers who ever defeated the legendary Satchel Paige.

The record for wins at the age of 17 in the major leagues is five, set by Bob Feller in 1936. In 1953, Dennis Biddle, pitching in the Negro leagues, equaled that number. Then he turned 18 and won ten more, giving him 15 wins in his rookie season. Injury derailed Biddle’s baseball career when he was only 19, but he got back on a successful track a few years later by returning to college.

Although the fame that may have come with baseball escaped him, he has enjoyed a long and rewarding life as a social worker, helping young people. At the time Biddle’s career began in 1953, blacks were making in roads into organized ball. But most major league teams still preferred white players. These were the days of the bonus babies, when money was spent by the hundreds of thousands of dollars on young talent. Not one bonus baby was black. So it was not surprising when 17-year-old Dennis Biddle did not receive any offers after his senior year in high school, even though he had hurled seven no-hitters.

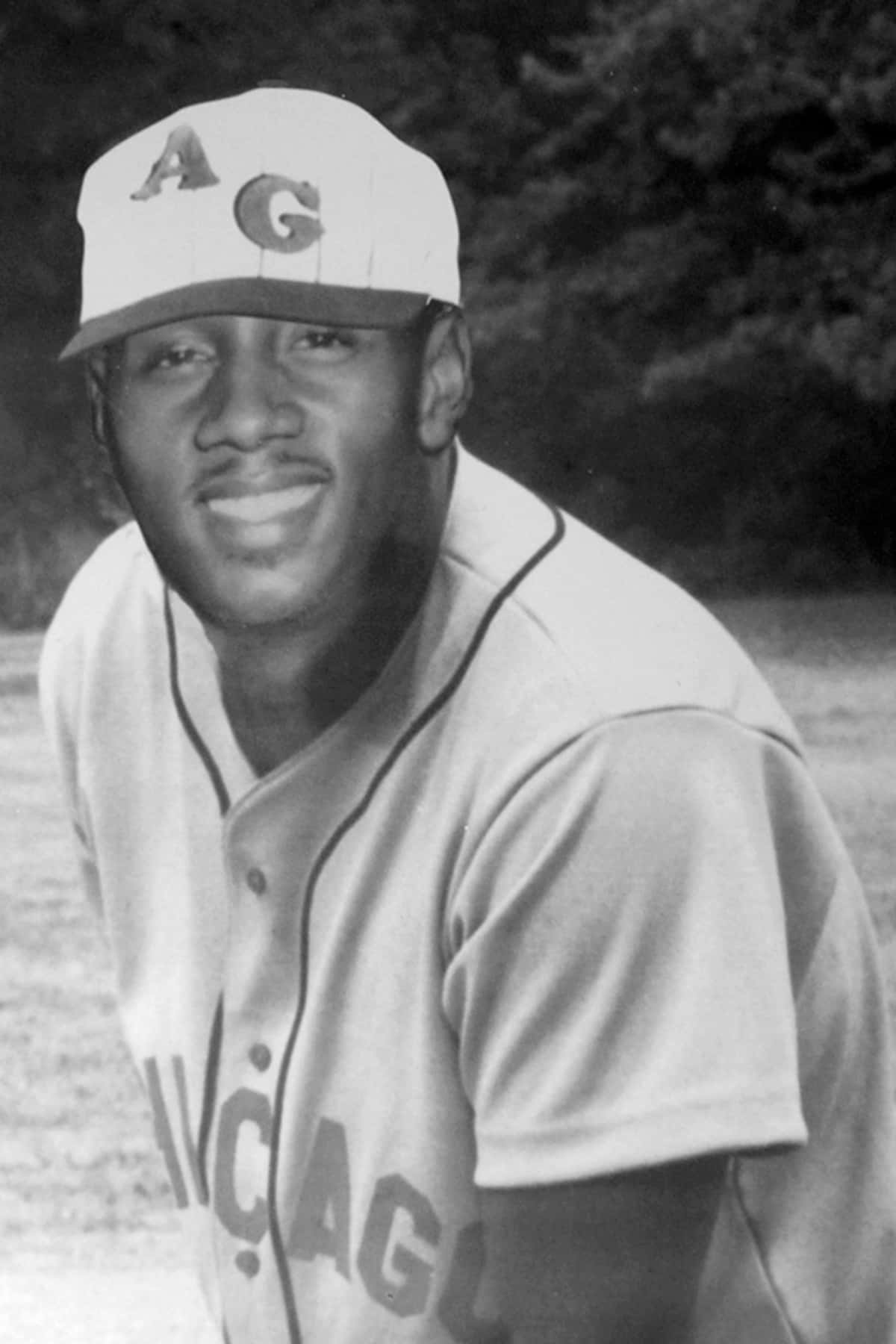

Negro baseball was dying then as the top Negro league players were being taken by Organized ball. But the last of the Negro league teams were still operating and developing players such as Ernie Banks, Gene Baker, Elston Howard, and a batch of others. Biddle signed with the Chicago American Giants, if he had avoided a fluke base running accident that ended his career after two seasons, he may well have joined that list. He played for the Chicago American Giants in 1953 and 1954.

Q&A with Dennis Biddle

Milwaukee Independent: How old were you when you began?

Dennis Biddle: Seventeen. I’ve been put into the Congressional Record as the youngest to play in the Negro Baseball League. I played two years in the Negro League, then the Chicago Cubs were interested in purchasing my contract. Matter of fact, they were purchasing it .I reported to spring training, and I broke my leg the first day of spring training in 1955. I jammed the bag sliding into third base, broke my ankle in two places. I was an excellent slider but somehow I cut my slide short and jammed the leg. It was one of those freak accidents. I still limp. When you look back 40 years ago, they didn’t have the modern-day medicine they have now. They didn’t operate on it like they would do now and make sure that everything was okay.

Milwaukee Independent: How did the American Giants get you?

Dennis Biddle: I was playing in the state championship in Arkansas for the National Farmers’ Association. That was the conference that we were in. We couldn’t play in the regular state conference because that was white. I pitched a 1-to-nothing no-hitter in the championship against a team named Eudora. A scout and booking agent for the Chicago American Giants saw me pitch and asked me if I would like to try out with the Chicago American Giants. Now, when he told me this I didn’t know anything about the Negro Baseball League. I thought it was a team that would be traveling down through there and I would try out for the team nearby. So I said, ‘Sure, I would like to,’ and he said, ‘I’ll have somebody call you.’

I gave him my telephone number. This was on a Friday. That Sunday I got this phone call as we were getting ready to go to church. The guy said, ‘My name is Frank Crawford from the Chicago American Giants. How would you like to try out?’ I said, ‘I would love to.’ He said, ‘Well, be in Chicago Tuesday morning, 10:30, Washington Park, diamond number seven.’

I’d never been out of my hometown of Magnolia, Arkansas. I told Mom, I told my dad, and my sister. I said, ‘I gotta go.’ We didn’t have any money. My dad, he was crying. My sister was crying, but my mother gave me the strength I needed, and also the money. I don’t know where she got the money, but she gave me twenty dollars. It cost me fourteen dollars to catch the interstate bus one way from my hometown to Chicago. She hugged me and she said, ‘Baby, good luck.’

I caught the bus, got off in downtown Chicago on Randolph Street. They had the moving steps, escalator stairs that I’d never seen them before. I saw these steps and I was afraid to get on them, so I walked up the stairs to the street. I saw a local bus and people were getting on it, so I got on there. I asked the bus driver how to get to Washington Park. He said, ‘I’ll tell you where to get off because you’ve got to transfer.’ So eventually I got to the park at Fifty-first and South Parkway. The name of the street now is King Drive, but it used to be called South Parkway.

I walked across the street and there was this guy sitting there. I asked him could I leave my bag there, would he keep my bag util I came back? I told him I was looking for diamond number seven, I had a tryout. He said, ‘Sure.’ I got my glove and my spikes out of my bag and I left it with him and I walked across the street. I didn’t have to walk too far before I saw diamond number seven, so I sat there, waiting for Crawford. That’s all I knew, Mr. Crawford. Two or three guys showed up and then finally Mr. Crawford came. We started throwing and about six or seven other guys came down and I tried out for the team. He had a contract right there already typed out. I’ve got a copy of the contract now. I signed my contract and three days later I was pitching my first professional game in Memphis, Tennessee.

Something happened on that tryout day that followed me for a long time. This gentleman that I had left my bag with became like a father to me. Crawford had a room for me on 47th and South Parkway. He said, ‘Where’s your bag?’ and I said, ‘Across the street over there.’ He said, ‘Where?’ I went over there and I was lucky. A lady said, ‘Are you the young man that left your bag here? Mr. Washington had to go to work and he said you would be back for it.’ I said, ‘Could I have his telephone number?’ I took it to the hotel with me and I didn’t sleep all night long. I have never heard so many sirens. I couldn’t wait util daybreak so I could call him. I called him, he came down, picked me up that morning and he said, ‘Get your bag. You’re going with me.’ Twenty-eight years later, I buried him. He went through everything with me.

Milwaukee Independent: How much were you paid?

Dennis Biddle: Five hundred a month. Six games a week. We played a lot of money games. A money game is where the booking agent would book us in a town with the local team. Twenty thousand people would come out to see that game. Paying a dollar apiece, that was a big payday for us. That money was split 60-40 by the teams. Of course, they were league games and it was really hard riding that bus from city to city and playing all those games. There were only 16 players, so we played every day. Besides pitching, I played center field and first base. I batted left and right.

Milwaukee Independent: Do you remember your first game?

Dennis Biddle: Oh, yeah. I got my game ball. I kept the ball. I didn’t know the significance of it. I gave it to my son when he was 6 years old and he kept it. For years we didn’t even talk about the Negro League. The only time I talked about it was with my kids and my grandkids. It was something that was a part of my life that had come and gone. Nobody was talking about the Negro Leagues, everybody was talking about the guys that were playing in the Majors. My first game was against the Memphis Red Sox. My catcher was Double Duty Radcliffe and he was an old man, but he was still good.

I struck out 13 batters and I gave up one home run. The score was 3-to-1. I didn’t know the guy’s name, all I knew is they called him “Big Red.” He hit a home run off of me that’s still going today, I think. I had struck him out twice and Double Duty had come out and told me to throw him a curveball. I saw him step up in front of the plate so I knew he was waiting for my curveball because that’s what I struck him out with, so I was going to cross him up and throw the fastball. Double Duty said, ‘Throw the curveball!’ and I shook him off. I threw the fastball and this guy hit it. Double Duty came out and yelled at me, ‘Boy, I’ve been in this league 25 years! When I tell you to do something, you do it!’

“Big Red” had to weigh close to 300 pounds. He was big and tall, and every time he’d swing that bat and miss the ball, it looked like I could feel the vibration of the bat out there. He could swing hard. (NOTE: “Big Red” may have been catcher Pepper Bassett. He fits the description: 6′ 3″ and probably 240 pounds at the end of his career in 1953.)

I won my first five professional baseball games, all while I was 17. The second game was against the Philadelphia Stars in Racine, Wisconsin, and that’s how I got my nickname as “The Man Who Beat the Man Who Beat the Man.” I was pitching against a guy by the name of Lefty McKinnis. He was a legendary pitcher that everybody was talking about how good he used to be. He was one of the very few pitchers that ever beat Satchel Paige. I only found that out after the game. During the game, he was always talking to me, telling me, ‘Hey, kid! You’re telegraphing your pitch.’ And I’m saying, ‘I don’t know what he’s talking about, telegraphing my pitch.’ My manager told me, ‘The batter knows what you’re about throw before you throw it.’ I said, ‘So. They still can’t hit it.’ was my reply. But he said, ‘Son, let me tell you something. A batter’s trained to watch the ball all the way from the pitcher’s hand. The longer you keep it covered up, the more effective you’ll be because it’ll take him time to pick it up.’ He showed me how to do it and every game after that, and even today when I teach young pitchers how to pitch, I use the same technique that he showed me that night in Racine, Wisconsin.

I won the game 5-to-1. After it everyone said, ‘Hey, kid, you just beat the Man.’ I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ ‘He’s one of the very few pitchers ever to beat Satchel Paige. He’s the Man.’ From that night on, they called me “The Man Who Beat the Man Who Beat the Man.” I had 30 wins in two years, only seven defeats. The first year our schedule was 71 games, the second year was 73 games. The first year I played in 18 games and I had a 15-and-3 record. My second year I had a 15-and-4 record. The Cubs were following me. As I look back, those days and nights we were riding the buses and we’d get to a stadium, the scouts would be all over me and I could see the older guys sitting there with a sad look on their faces. Being a social worker and taking psychology, I reminisce back to when this was happening and I know they were happy for me, but there was some resentment. You know, the fact that they had been passed by and there was always two or three young guys on the team, these were the guys the scouts would be talking to.

And those older guys were great. I saw this with my own eyes and I was only a kid. I can imagine what they were like when they were kids. If you talk to the older guys now, they will tell you they have no bitterness, this is the way things were. The older guys were training us. Cool Papa Bell trained me. I was fast. I could run real fast and I remember distinctly Cool Papa Bell coming to the Chicago American Giants, coming to our games and traveling with us on the bus. He was too old to play. He was like a mentor. I think the Major Leagues were paying him a salary. I can’t prove that, but he didn’t only talk to me, he’d be talking to the other guys on the other team, too. He would always find something somebody was doing wrong and he would correct them. Like for me, I was fast but I would round the bases and lose a lot of time.

After the games or early in the morning, he would take me out to the park and he would walk through it with me. He didn’t smoke and drink. After the game the older guys, they’d be going to parties and stuff. I was too young to go and Cool Papa would always stay with me and he would tell me stories about some of the guys. I learned a lot from him about some of the great players in the game down through the years that you don’t read about in books because they didn’t set any records and get attention.

Milwaukee Independent: Is there one game that stands out as your best game or biggest thrill?

Dennis Biddle: The first game was my biggest thrill, I was in a daze for a couple days. I had a terrific curveball, and I didn’t believe people could hit my curveball and my sinker when I started playing. I remember I struck out Buck O’Neil in Omaha, Nebraska, one night. We went to the eleventh inning and I came in the tenth inning to pitch. We scored a run in the eleventh inning. I think I walked a guy, then somebody made an error. The guy was on second base and Buck came up to pinch hit and I struck him out. I didn’t know him then. I didn’t know he was the Buck O’Neil util years later. That ranks up there with the biggest thrills, striking him out. The score was 5-5 going into the eleventh inning and we scored that run, then I struck Buck out and that was the end of the game. He was the last out.

Milwaukee Independent: Who was the best hitter you saw?

Dennis Biddle: I saw a lot of good hitters. The guy I was with a lot was Double Duty. Ted wasn’t a young man anymore but he could still hit that ball. A lot of guys could tear the cover off the ball but Double Duty, I remember him distinctly hitting long home runs. There was a guy named Dick Vance. He was a catcher and he could hit some long balls. I saw a lot of guys and I don’t remember all their names. I saw some great ballplayers, some guys that were too old to go to the Majors, they were still playing and they were great. They could hit that ball. I wonder sometimes why they were not in the Majors. It had to be their age, Jackie was 28 but he was exceptional.

Milwaukee Independent: What about the best pitcher?

Dennis Biddle: I saw a lot of great pitchers, and I modeled myself after them. A guy that I remember was with the New York Black Yankees. He was a Cuban guy and he did go to the Majors. His daddy played in the Negro Leagues also, they said. Tiant could throw that ball. I got a picture with him in New York. They really talked about his dad. Cool Papa told me about how awesome his dad was.

Milwaukee Independent: After an injury forced you out of baseball you went back to school?

Dennis Biddle: That’s the reason I’m in Wisconsin. I went to the University of Wisconsin and became a social worker. I was employed for 24 years with the State of Wisconsin and retired in 2004. I was working in the corrections system and you can retire early, but I couldn’t relax so I started working for this social service agency called Career Youth Development (CYD). I was working with the same types of youth I had been when I was a social worker.

I went to school in 1958. I thought my leg was going to come around. The doctors kept watching it and I thought it healed. I could still run, but being a pitcher I kind of favored that leg on my landing. I couldn’t get the ball across much anymore. I still had the speed, but the whole thing just wasn’t there and I saw the light.

I said, ‘I better get my butt back in school.’ That’s what I really wanted to do when I graduated from high school. I had two scholarships, one from Grambling College to play football and another to Arkansas AM & N, which is now the University of Arkansas, to play basketball. But nobody recruited me for baseball. At that time for the black schools, baseball was not one of the money sports. I went to visit Grambling. Mr. Eddie Robinson took me down to visit the campus and I spent the night with Willie Davis. We’re good friends today because of that. We played football against each other in high school.

Milwaukee Independent: Would you be a ballplayer again in the same situation?

Dennis Biddle: As I look back, I would have gone to college, paid my way, and played baseball. But I’d play professional baseball again. I play now. They’ve got a league here they call the Old-Timers League. You have to be 30 or more and some guys 60 years old are playing. I’m the oldest one on the team.

Milwaukee Independent: What about the Negro league players you’re working with now?

Dennis Biddle: Fay Vincent, the commissioner of baseball, had ordered the Negro league players to be insured. Joe Black was given six months to find all the Negro League players. That wasn’t fair because these guys are all over the country and he only found a little over a hundred, about half. After he wasn’t able to finish in six months, the rest of the guys were left out. I felt that was wrong and I could not rest until I did something about it. Personally, I didn’t need the insurance, but one day I might. So I started investigating why the other players did not have it and as I got deeper into it, I found out a lot of other things that were never told to us. That’s why I started the organization, Yesterday’s Negro League Baseball Players LLC. The Negro League players needed a voice and our we can now make sure they get insurance and other benefits that were kept from them.