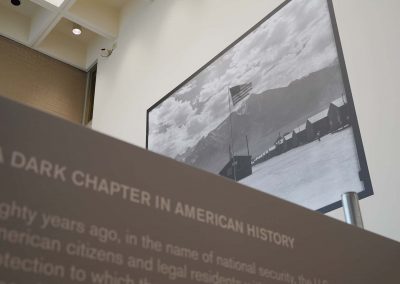

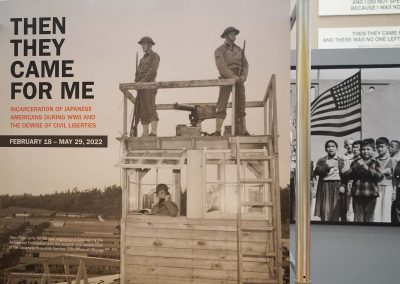

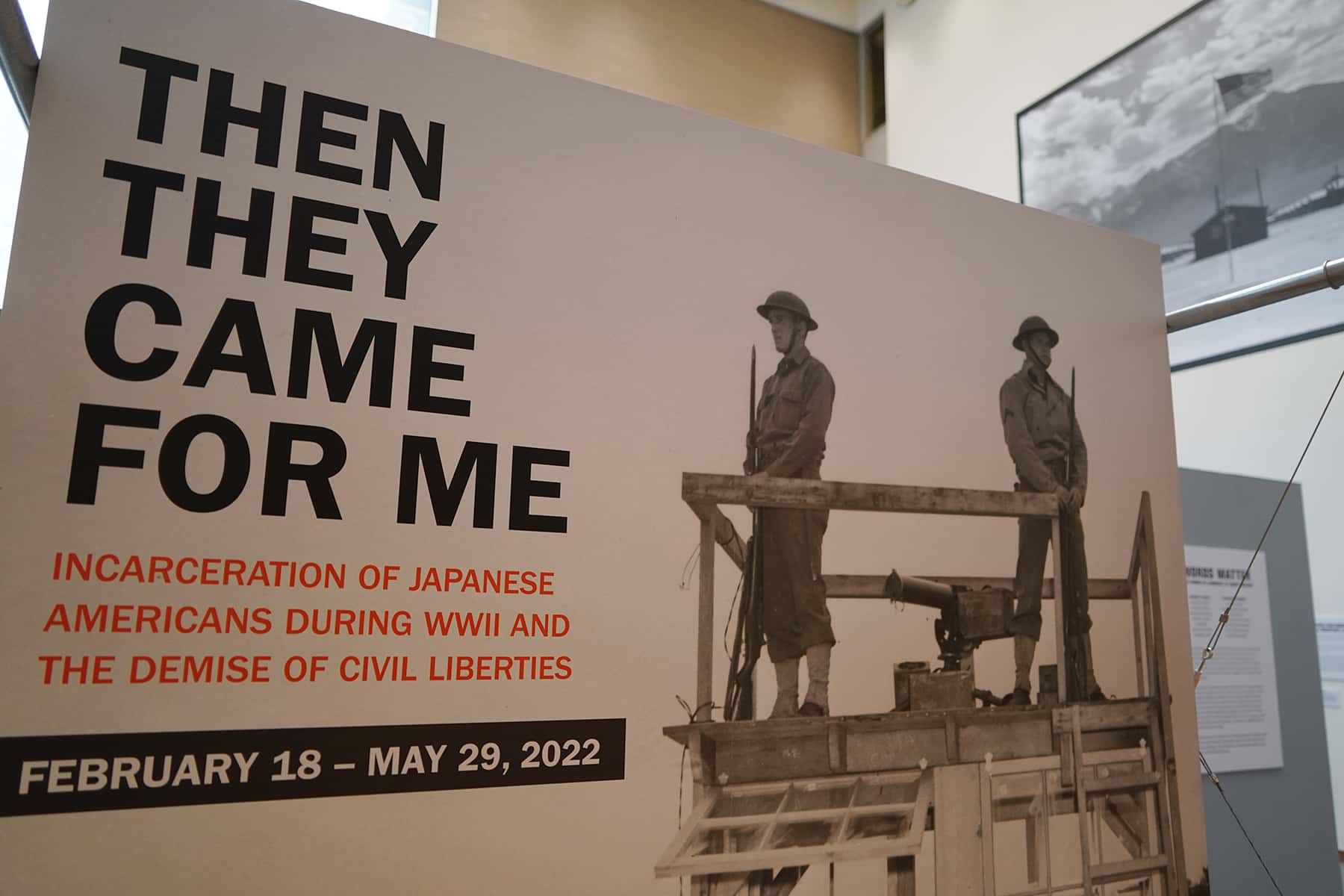

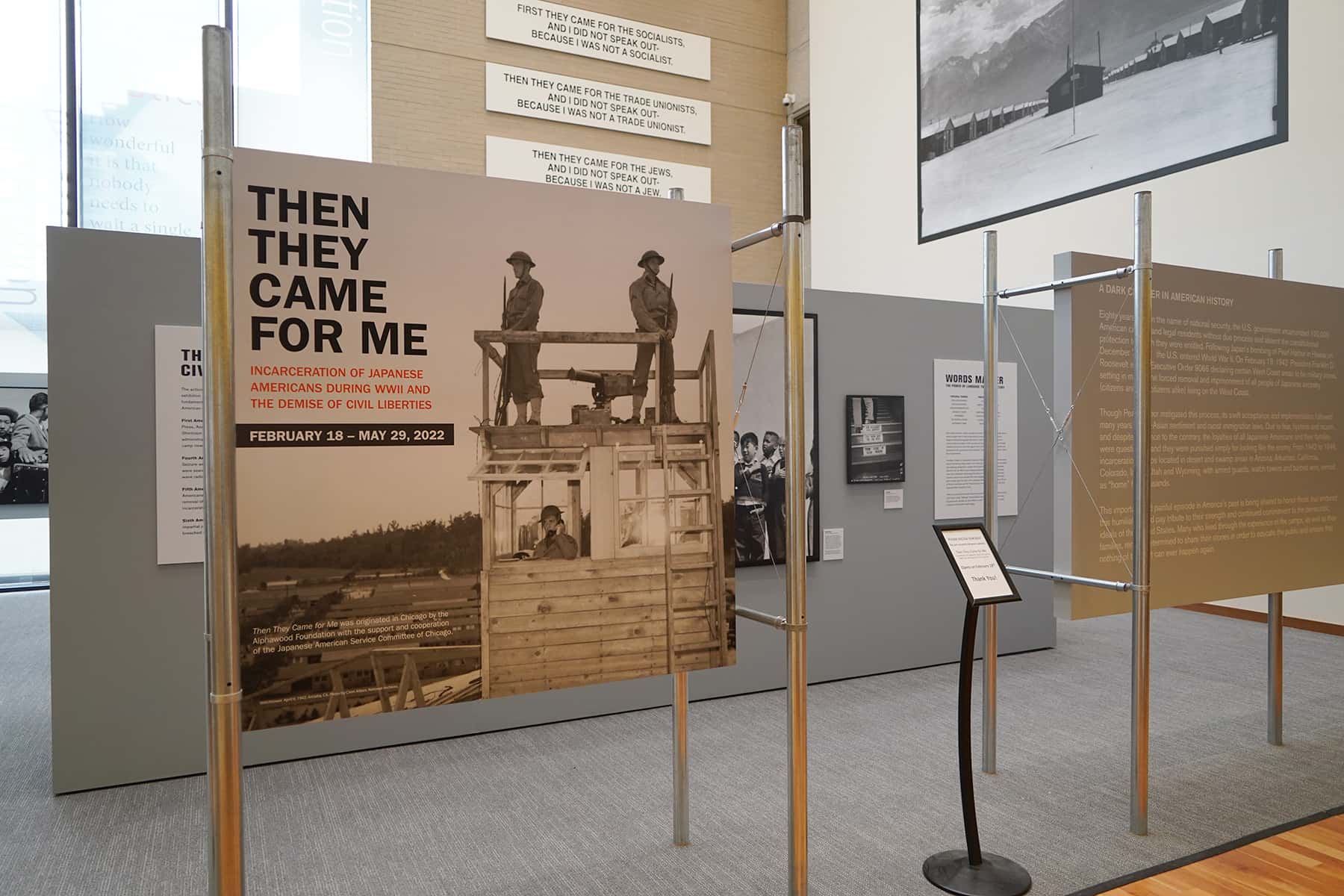

Jewish Museum Milwaukee (JMM) is presenting a major new exhibit, “Then They Came for Me: Incarceration of Japanese Americans During WW II and the Demise of Civil Liberties” from February 18 to May 29, 2022. The traveling display examines a terrifying period in American history when the United States government scapegoated and imprisoned thousands of people of Japanese ancestry.

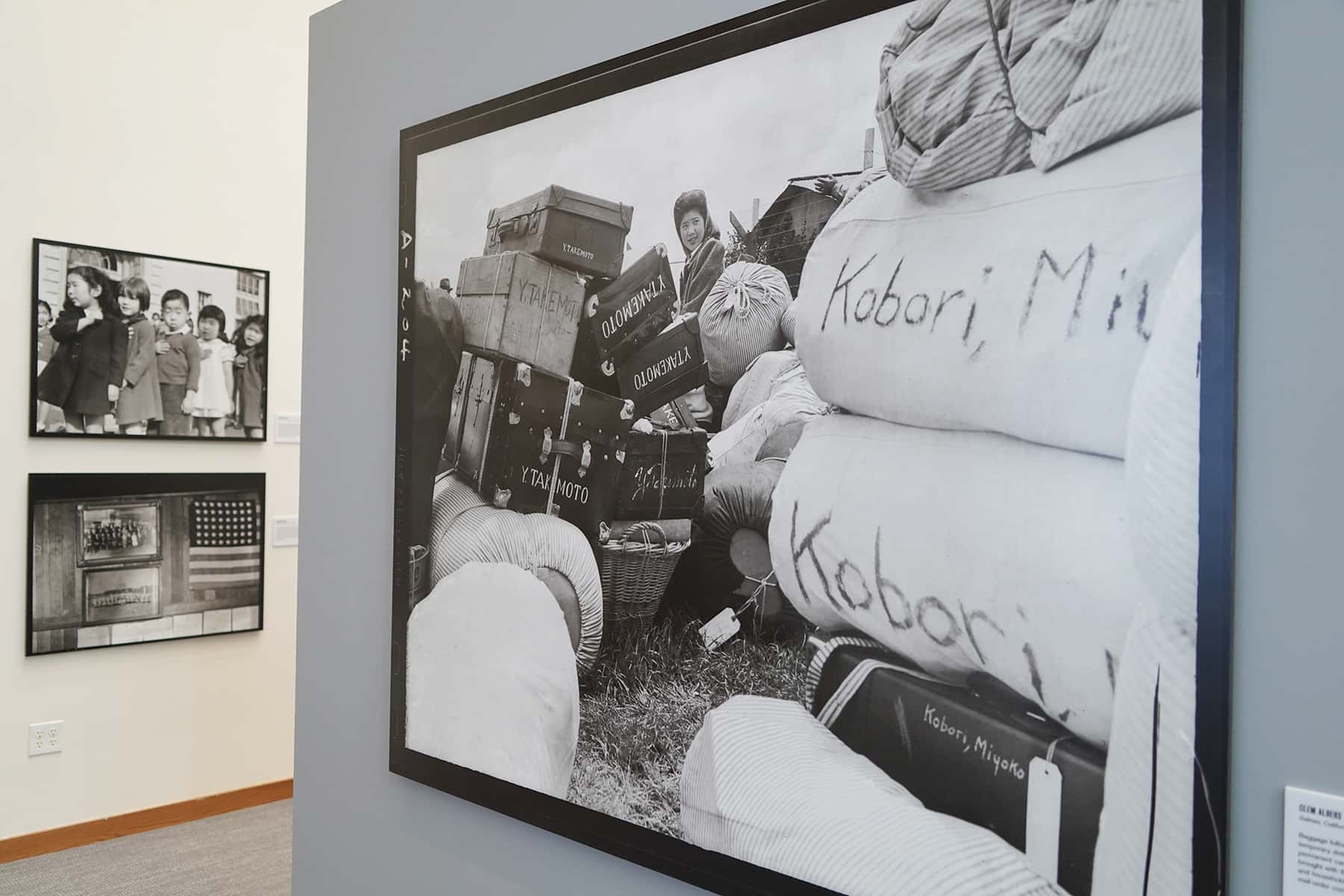

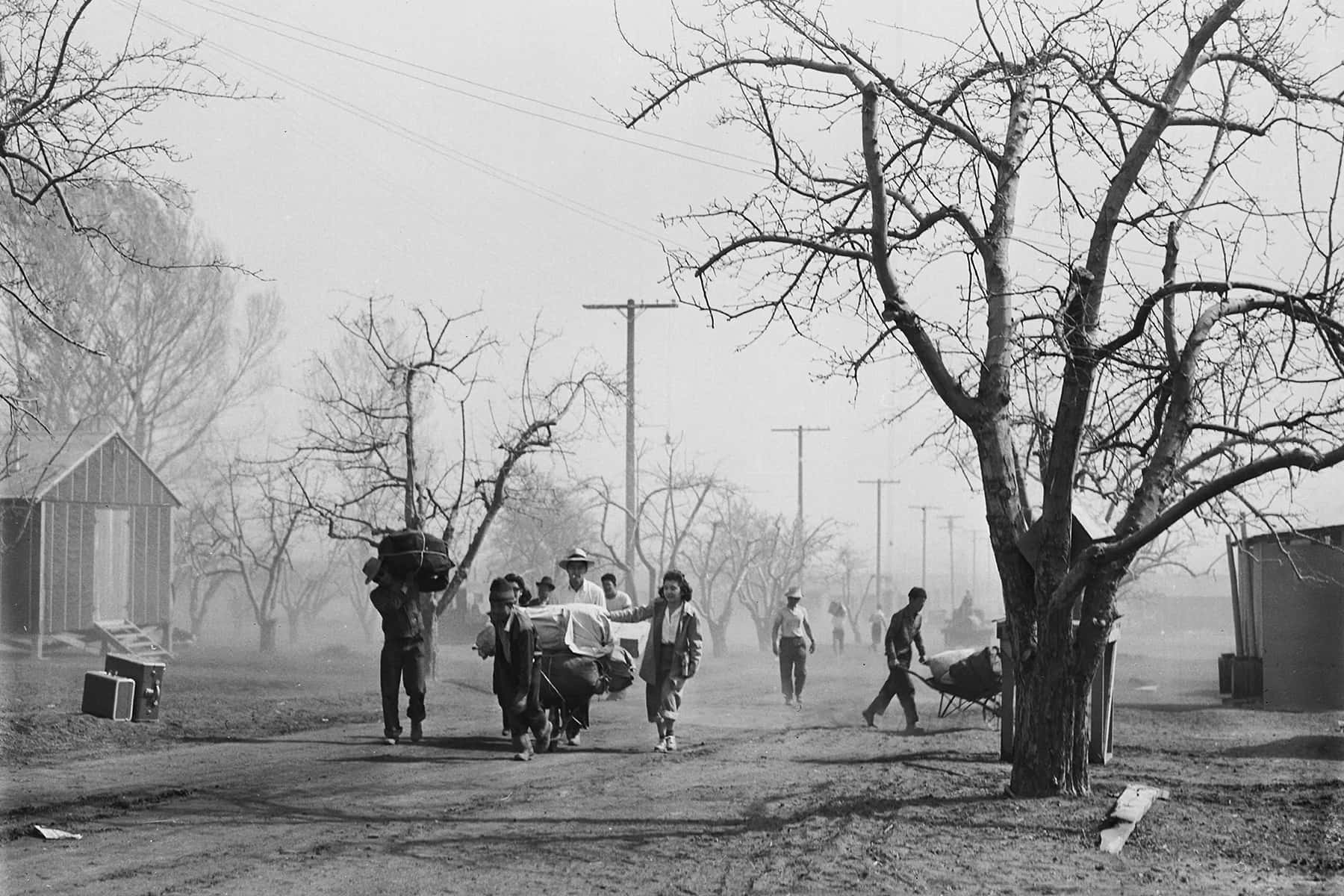

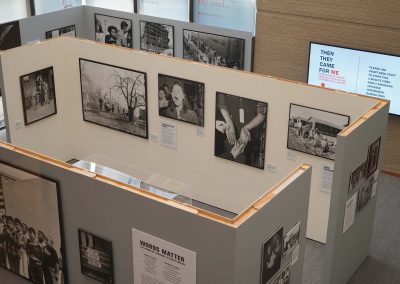

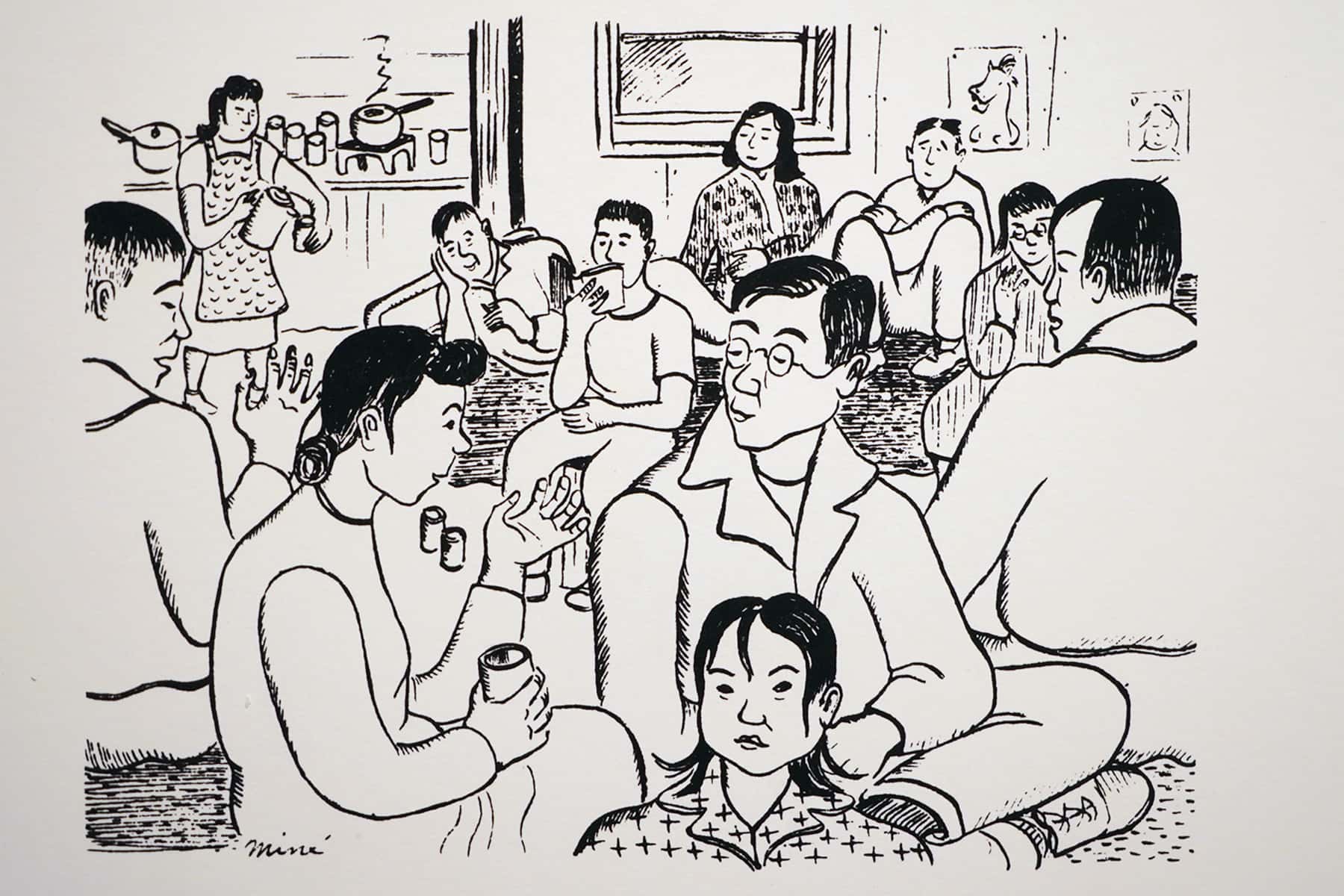

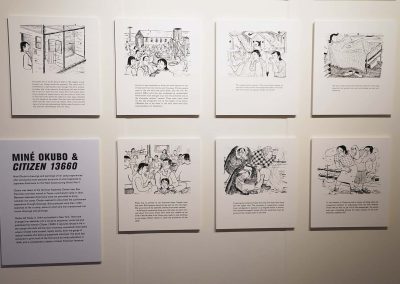

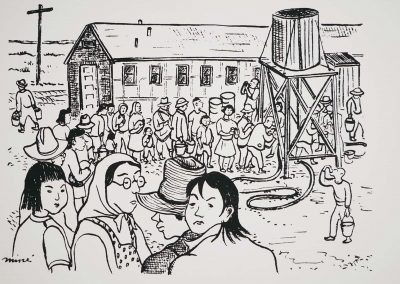

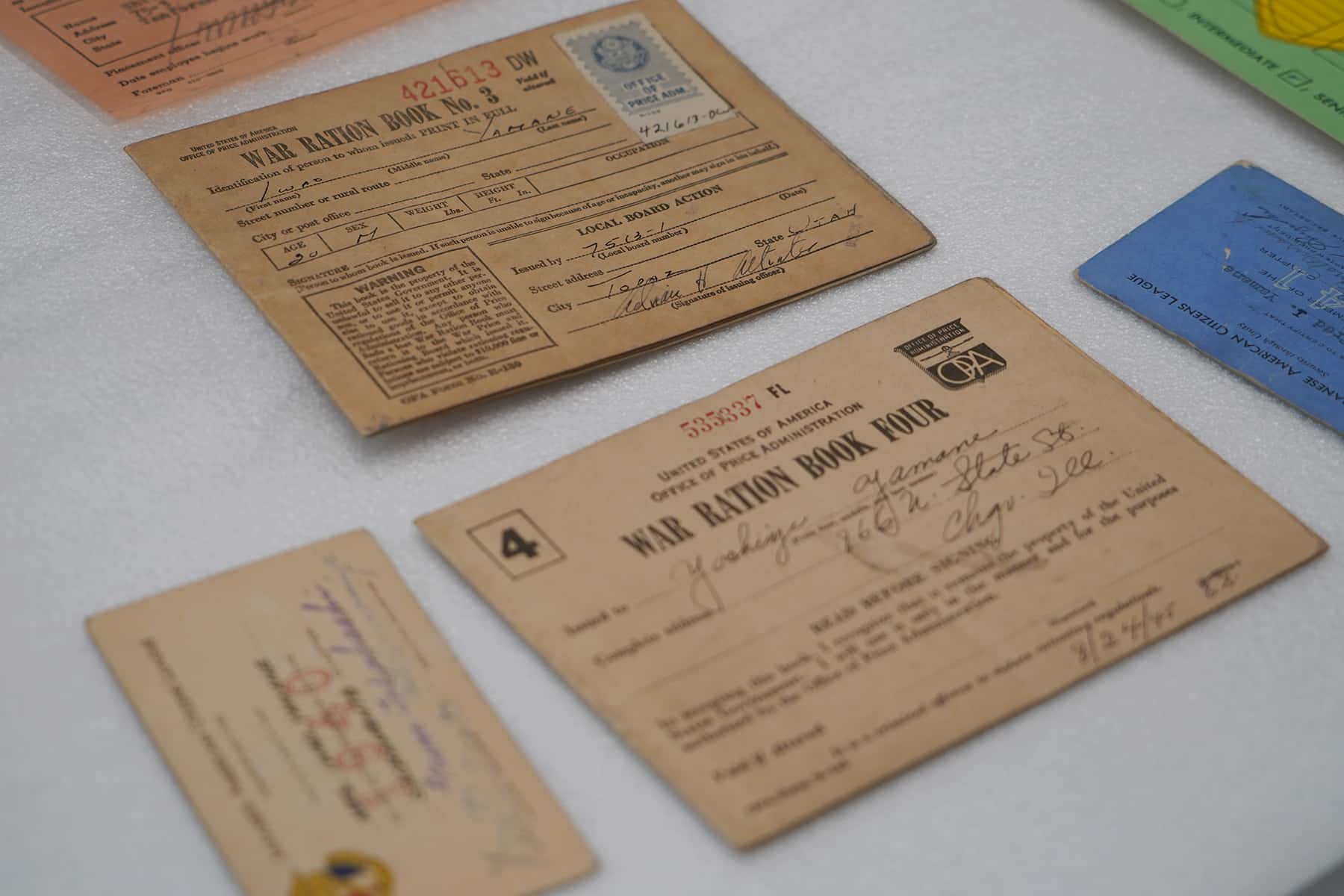

Using a variety of visuals from vintage photography to historical relics, “Then They Came for Me” illustrates the impacts and lasting effects that the wartime events had on those who experienced them. While at the same time, the exhibit reflects on the discrimination and intolerance surrounding the current immigration and refugee crises in America.

“When we look at Anti-Asian sentiment today in the wake of the last few years politically, and from the pandemic, there has been not only an incredible rise in Anti-Asian crimes, but a huge increase in Anti-Semitic activity,” said Molly Dubin, JMM Curator. “This exhibit features a group of people who were prejudiced against, based on unfounded information or fear. So we found it resonated with some of our experiences, our histories, our stories, this idea of a population of individuals being excluded and interned strictly based on their race, and justified by inciting public hysteria through propaganda.”

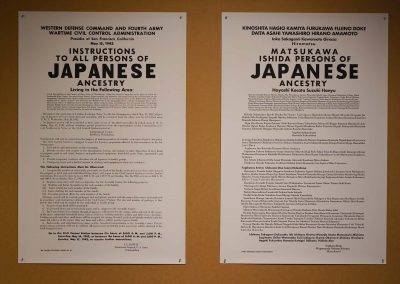

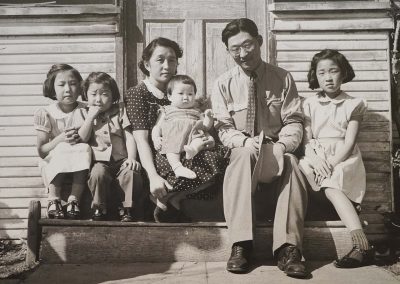

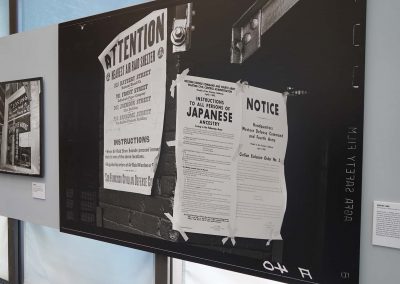

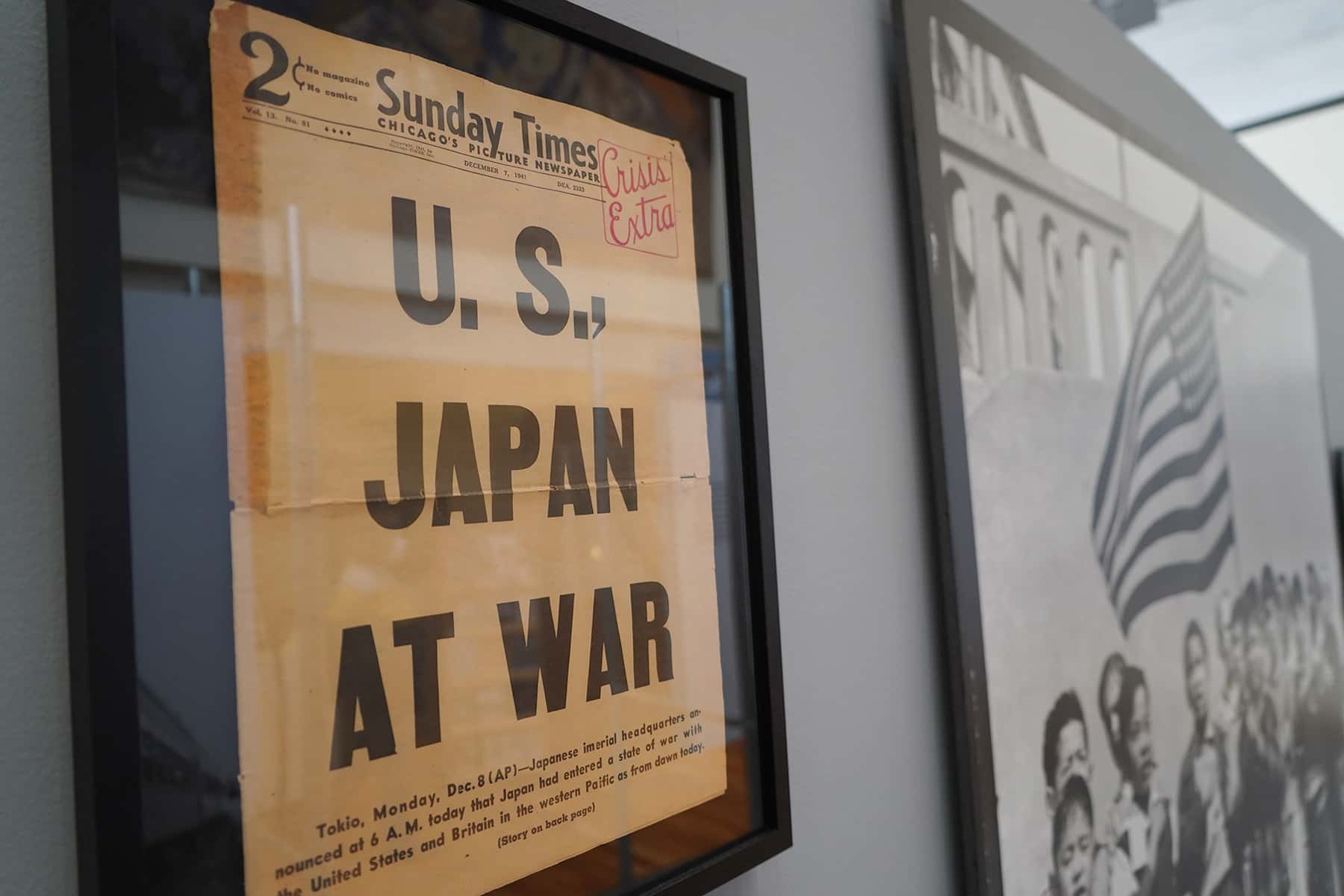

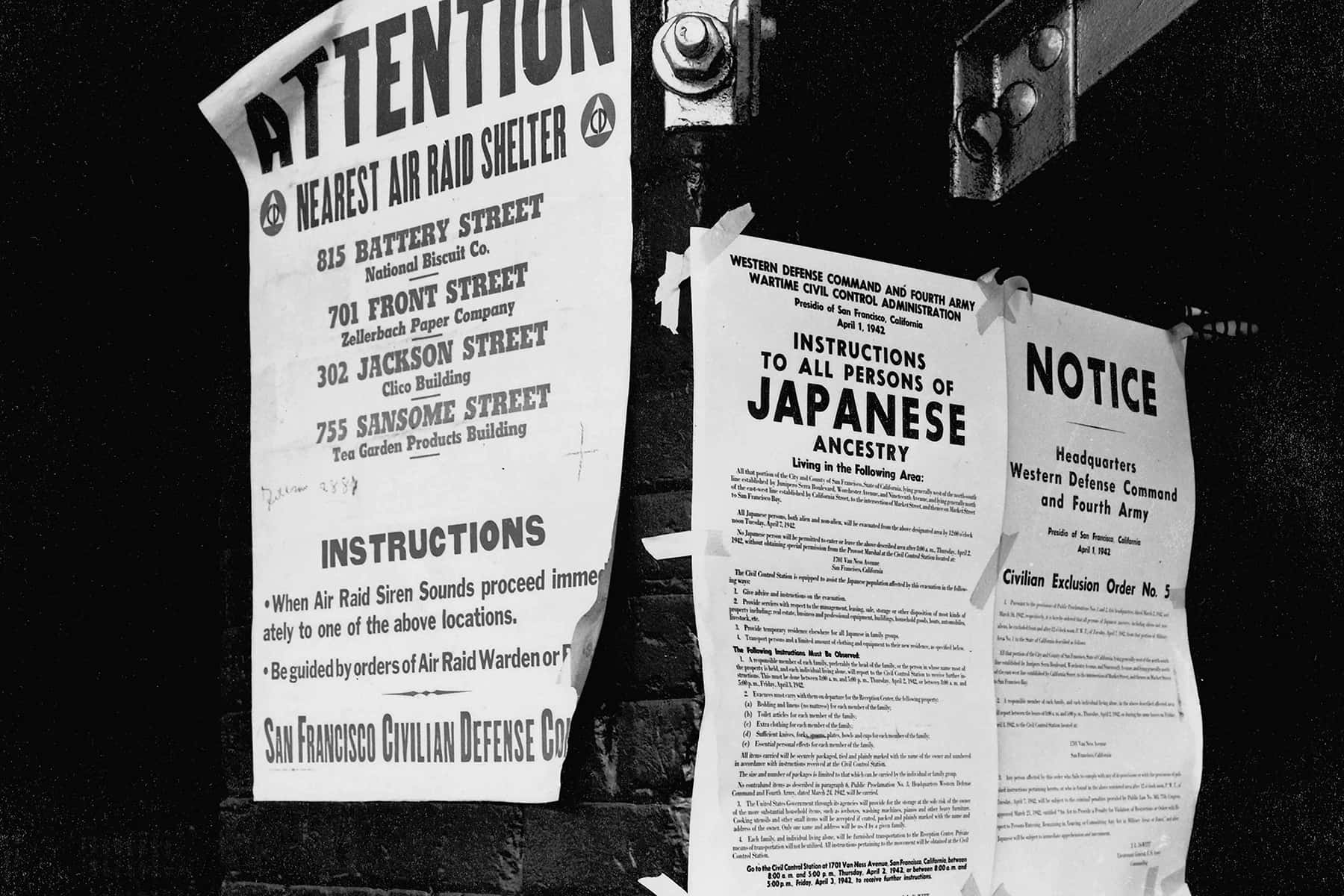

The message of “Then They Came for Me” surrounds the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the subsequent removal of Japanese American citizens and legal residents from their homes. The exhibit examines a painful piece of history where people were uprooted from their homes and lives, while often being separated from their families to be incarcerated based solely on their ancestry.

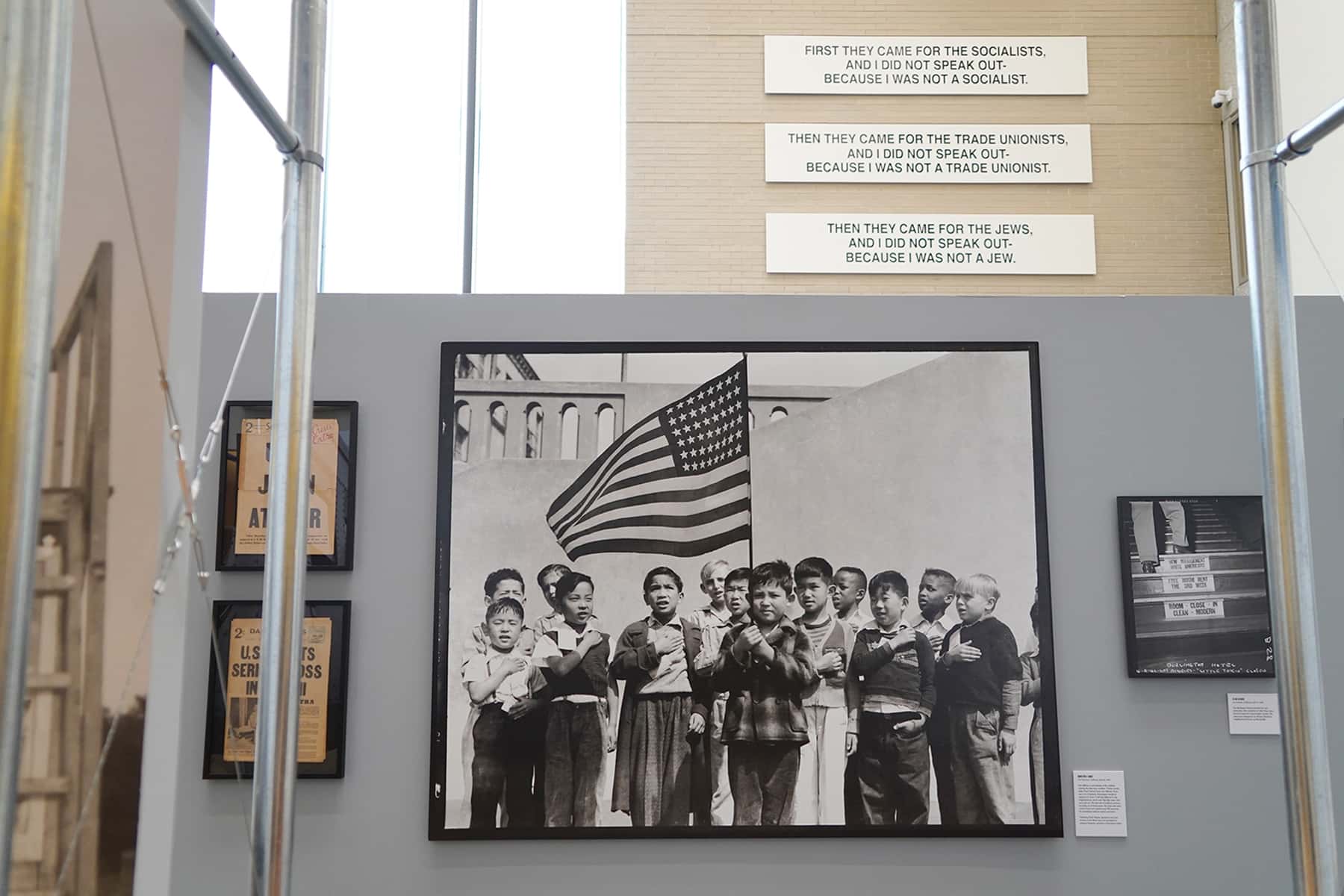

The title of the exhibit was taken from a quote by Martin Niemöller, regarding the situation when Hitler seized power in Germany:

“First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out — because I was not a socialist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out — because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out — because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me — and there was no one left to speak for me.”

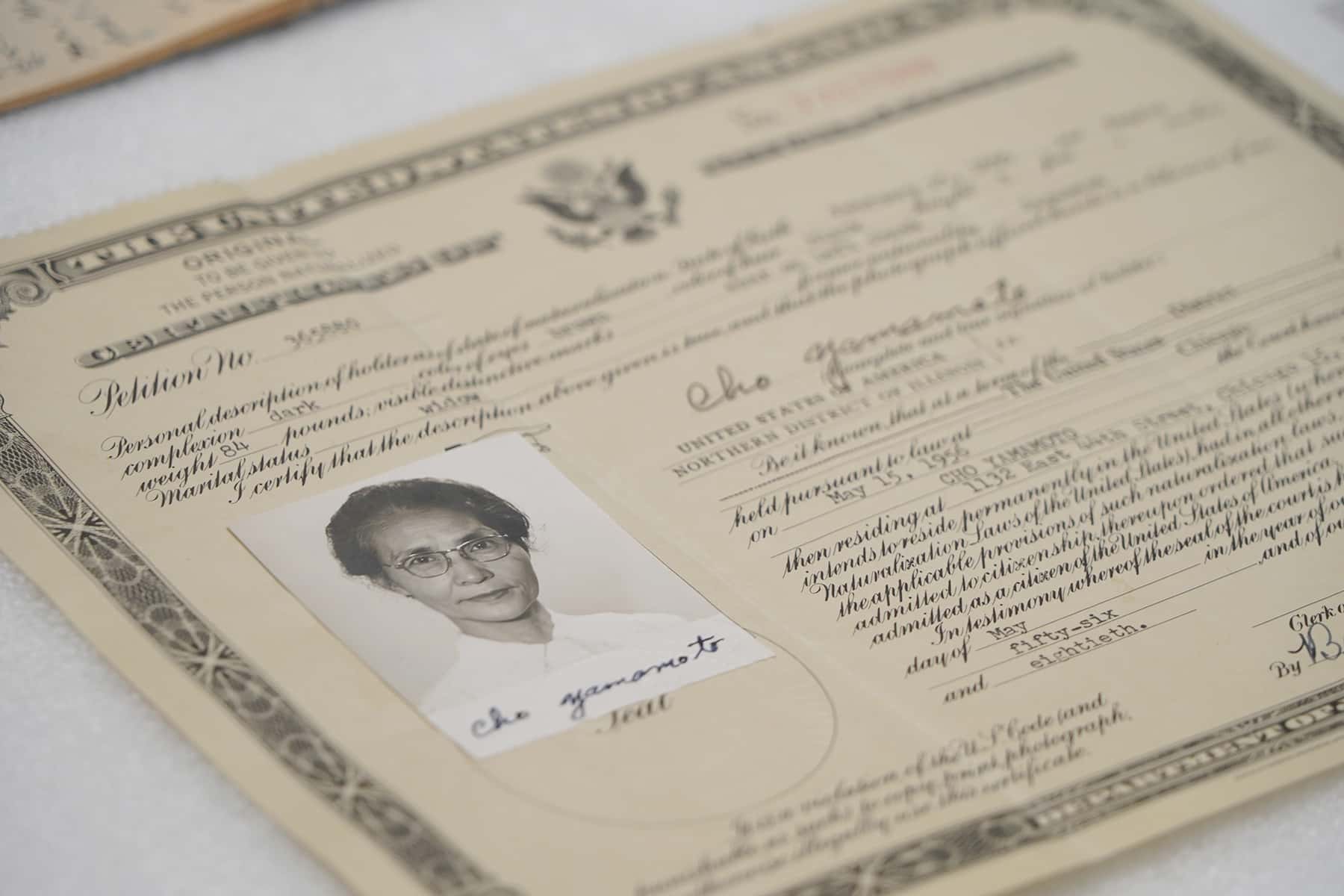

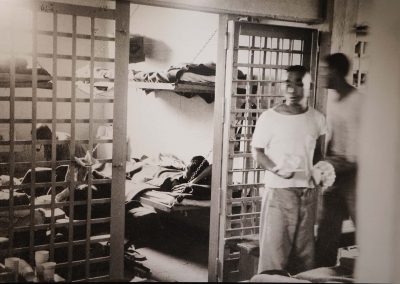

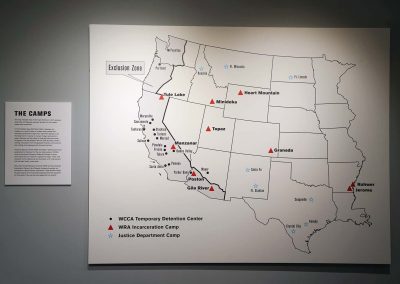

Executive Order 9066 was signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. The order cleared the way for the incarceration of nearly all 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. Two-thirds of them were U.S. citizens, born and raised in the United States. Decades later, Japanese Americans are still seeking restitution and reparations for what was taken from them.

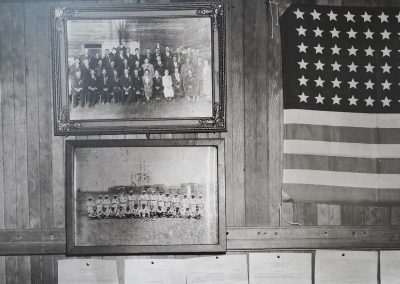

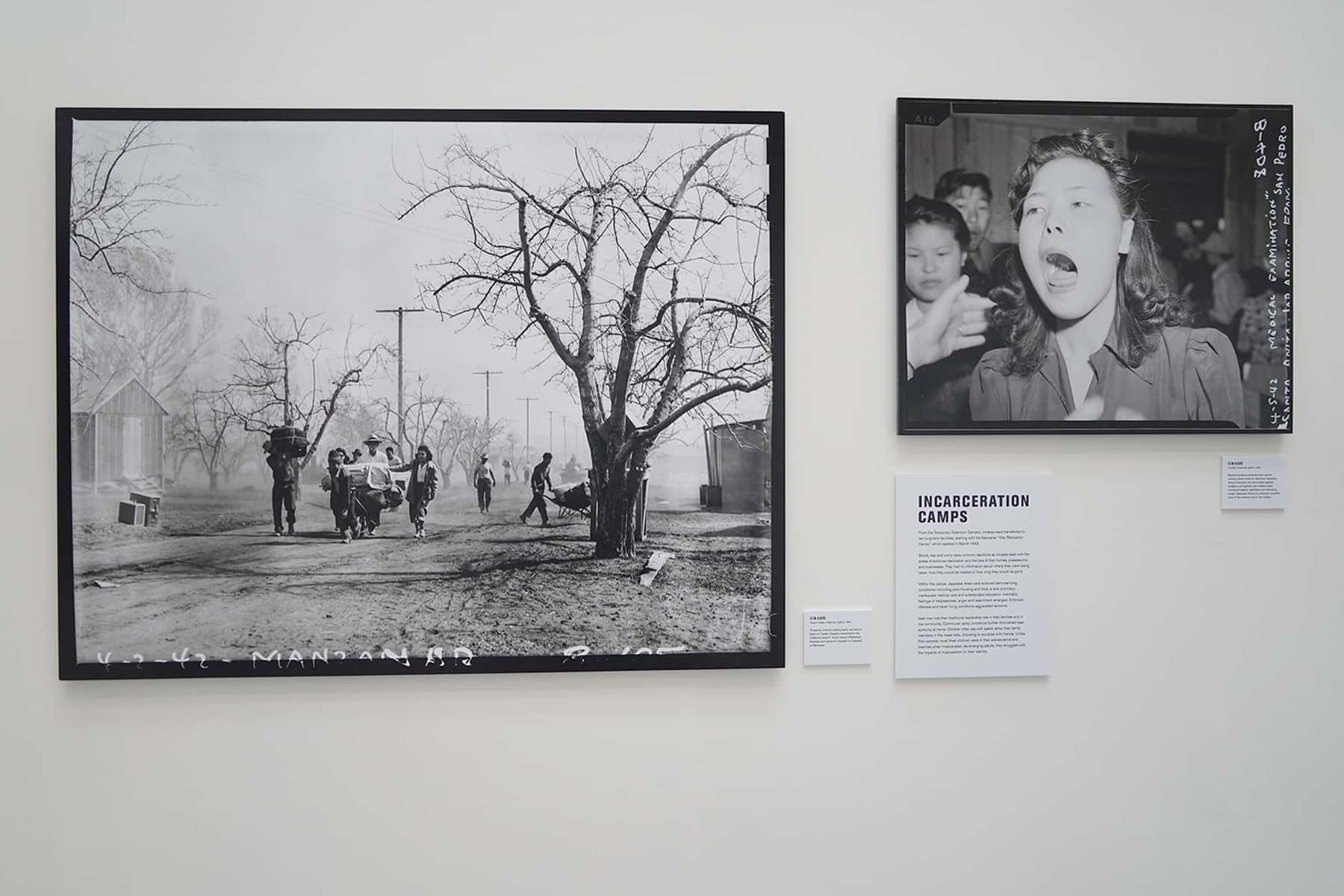

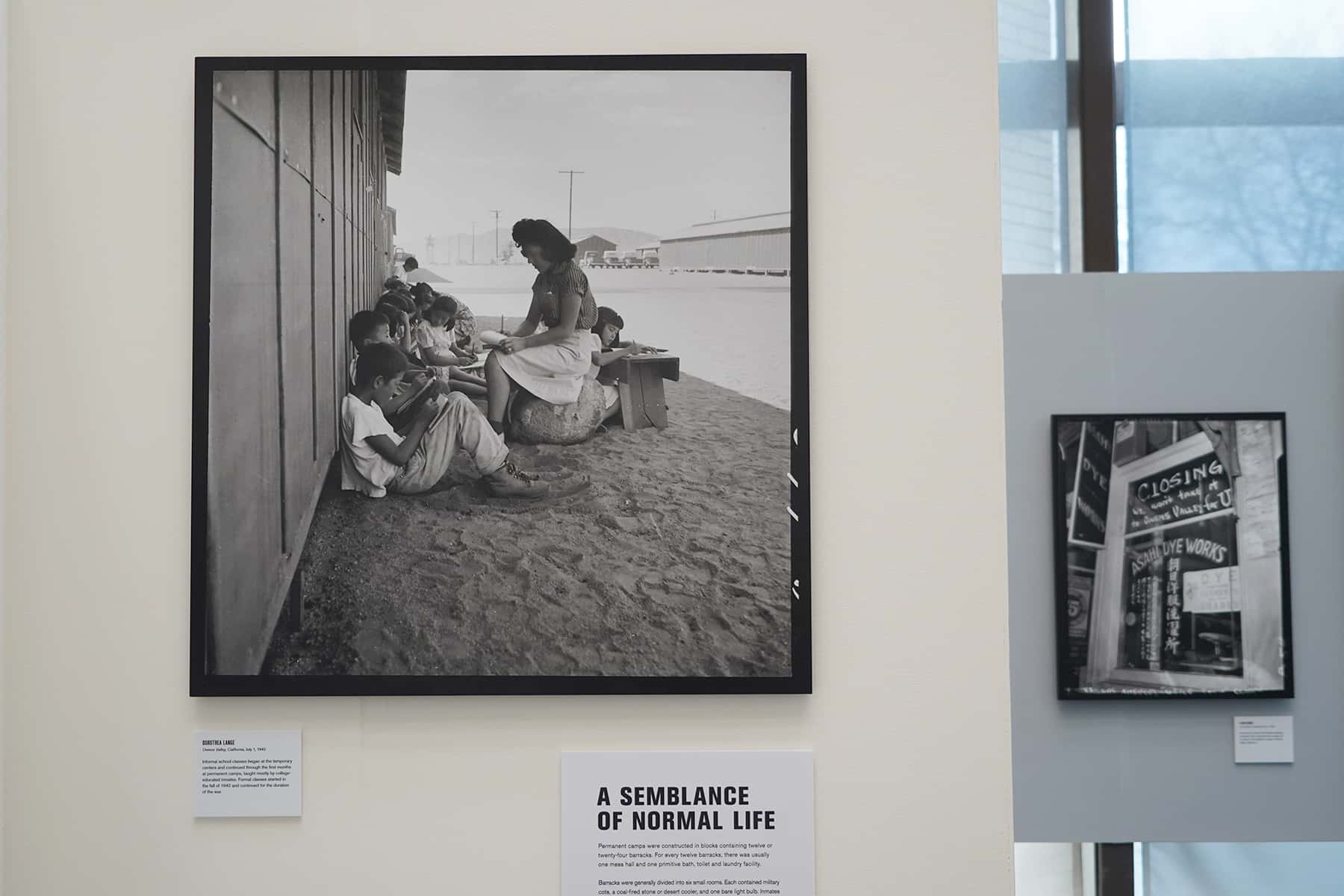

“Then They Came for Me” originated at the Alphawood Gallery – Chicago in 2017 and traveled to New York and San Francisco. The Milwaukee run is customized for the JMM space. The focal point of the exhibit is the use of large-scale images by prominent American photographers who documented the incarcerations, including Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, and Clem Albers, alongside works by incarcerated Japanese American photographer Toyo Miyatake.

“These amazing photographers were commissioned by the U.S. government to help control a narrative and spin public opinion against Japanese Americans,” said Dubin. “Dorothea Lange became, and rightfully so, very sympathetic to their situation. Ansel Adams was accused of that as well, and then he was also criticized for not capturing more of the internment camp conditions. But he counts the group of work that he did at Manzanar as the most important of his career.”

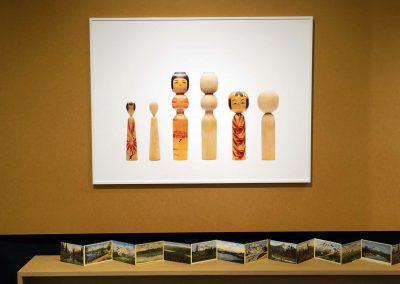

A selection of contemporary works by Milwaukee-based artist and photographer Kevin Miyazaki are incorporated in the exhibit. The youngest of four siblings, his late father Jim spent time incarcerated at both Tule Lake and Heart Mountain relocation camps as a young boy.

“The night Pearl Harbor was bombed, my grandfather was arrested in their Tacoma, Washington home. Like other important Japanese Americans on the West Coast, my grandfather was arrested immediately. Anybody who was important – a teacher, minister, or priest – my grandfather was a successful business person and local community leader – was arrested and sent to the Department of Justice camps. So he was separated from that evening for a year and a half from the family.” – Kevin Miyazaki

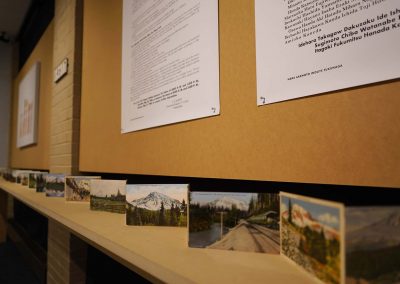

Also included with his work are a series of postcards of Mt. Rainier in Washington state, which had a deep connection for Miyazaki’s family and other Japanese immigrants because it closely resembles how Mt. Fuji looks in Japan.

A range of artifacts loaned by the Chicago-based Japanese American Service Committee are included with display, consisting of suitcases, ID cards and tags, anti-Japanese propaganda, hand-crated art, high school yearbooks, and newsletters produced by camp internees.

“I think it’s important to understand that this narrative was largely left out of our education. In public schools, in many instances, it was intentionally kept out,” said Dubin. “So there has been people involved with this project who did not realize what they didn’t know about this history.”

JMM partnered directly with the Japanese American Citizen League – Wisconsin Chapter to include local content through additional artifacts and oral histories. Video footage of individuals and families sharing their personal experiences highlight the impact that the pivotal event had on their lives.

The exhibit also addresses the very sensitive issue of terminology used to describe conditions for Japanese Americans. Semantics do matter, and it is important to understand context, how words are viewed from various backgrounds, and how the meaning of terms shift over time.

For example, a “concentration camp” has become a euphemism for a Nazi “extermination camp,” but the term itself predates Hitler. Nazi concentration camps in Europe are more accurately described as Death Camps, but American textbooks have been reluctant to use that description.

“Internment” has been a common expression used in specific reference to the forcible imprisonment of Americans of Japanese descent in the United States. Yet many Japanese Americans who were held for years at such facilities refer to them as American concentration camps.

The issue can be contentious, because some believe that calling Japanese relocation centers as concentration camps dilutes the experiences of Holocaust survivors. The exhibit presents this information from different perspectives to help educate the public, without taking a position on the definition.

A variety of programs also supplement the exhibit and include the history of Japanese American activism and intergenerational trauma stemming from incarceration.

The Yabuki Family Foundation has sponsored free admission to the Museum through the run of the exhibit. Jeffery Yabuki’s father George was incarcerated at a camp, and there is also a plaque honoring him.

“Through that support, many more people will have the opportunity to see this exhibit,” added Dubin. “And I think that really underscores what we hope to do, which is to educate about this really dark chapter in U.S. history.

- Nisei Soldiers: Japanese Americans fought Axis forces overseas and racial prejudice at home

- From Yellow Peril to Chinese Virus: The long history of racism against Asian Americans

- Japanese American National Museum says Justice Bradley’s reference to Korematsu case is offensive

- Justice Bradley’s ignorance of history: “Safer at Home” order is not like the internment of Japanese Americans

- They Called Us Enemy: Graphic novels teach youth about racism and social justice

- Who Counts and When: On Citizenship, the Census, and the Enduring Specter of Korematsu

Lee Matz, Ansel Adams, Clem Albers, Dorothea Lange, and Toyo Miyatake