In recent months, I have had the privilege of traveling to places in Southeast Wisconsin that I never visited before.

Some of these communities are just a short drive from my home in Milwaukee, but they seem to be a great distance away in some respects. I was invited to these communities to speak to adults and children about race. I never imagined that those communities would be interested in hosting a presentation related to race relations.

I have been pleasantly surprised at how open those suburban towns and cities have been to such a difficult topic.

We live in the most segregated metropolitan area in the nation according to a metric called a dissimilarity index. The index is designed to show how evenly dispersed people of color are as compared to whites within a metropolitan area. The range of values is from zero to one hundred. One hundred means that the group is not evenly dispersed throughout the geographical area, and is concentrated into clusters instead. These are the least diverse and most segregated communities.

The measure of segregation most commonly talked about is black/white segregation. The dissimilarity index for the regional metropolitan area, which includes Milwaukee, Waukesha, Ozaukee, and Washington counties, is eighty one. That places our community at the top of the list of most segregated metro areas in the nation. We have been near the top of the list for decades.

I have discovered how segregated we are by looking at the population of Milwaukee’s suburbs and the so-called WOW counties (Waukesha, Ozaukee, and Washington). Based on data from the 2010 census, the last full count done, Milwaukee is surrounded by communities that are extremely non-diverse.

The city itself is very diverse, with blacks making up 40% of the population; non-Hispanic whites 37%, Hispanics 17%, and Asians 3.5% of the city’s population. Sixteen of the eighteen suburban communities in Milwaukee County have a white population above 79%, with Hales Corners the highest at 94.7%. The average in the suburban cities in Milwaukee County is 86.2% white. Waukesha County’s population is 95.7% white, Ozaukee County is 95.3% white, and Washington County is 96.7% white.

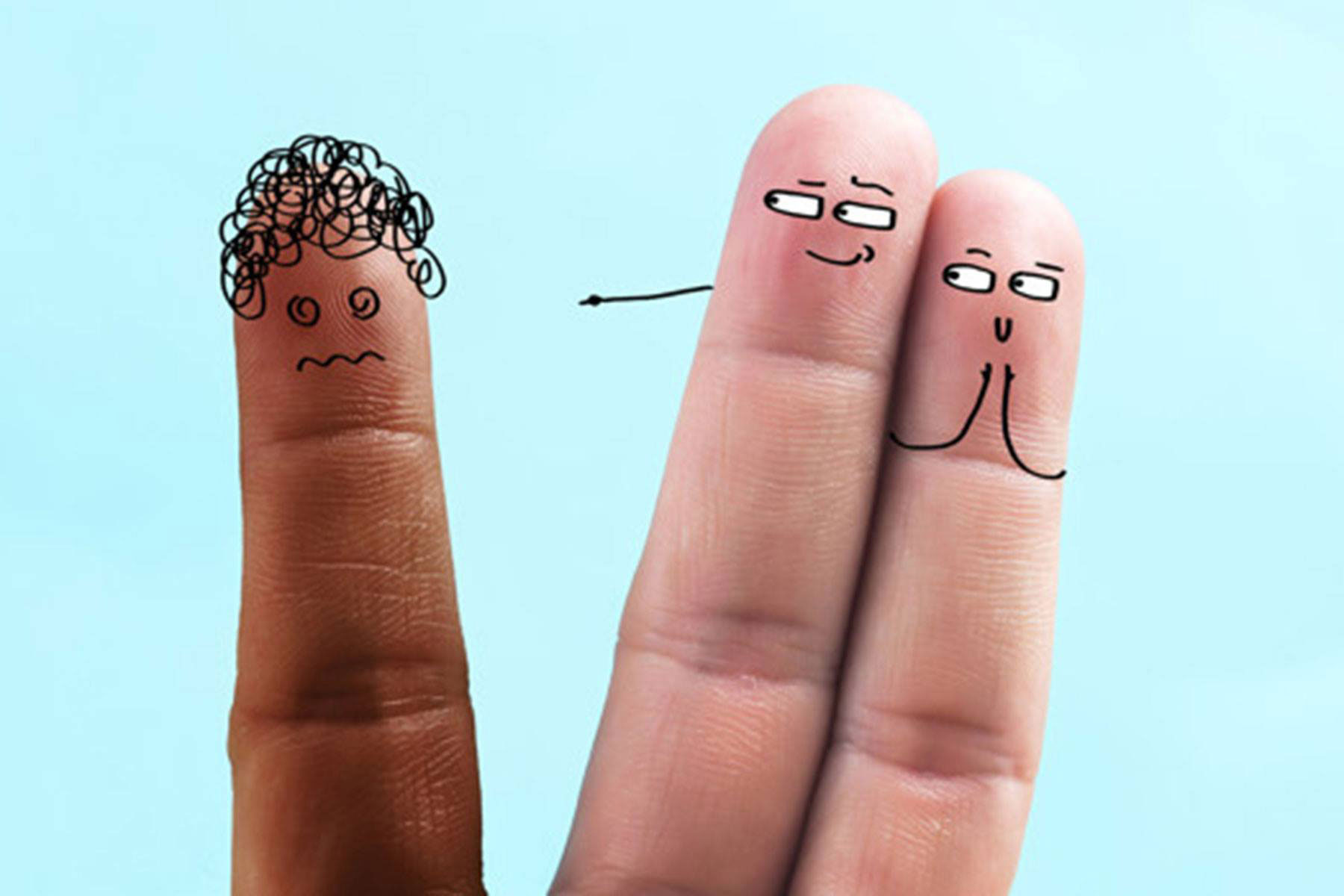

We occupy segregated spaces; our neighborhoods, schools, churches, shopping malls, and parks. Most Milwaukee area residents live a majority of their lives within racially homogeneous spaces. We generally have minimal significant contact with people who do not look like us.

Segregated spaces create a lack of understanding. We do not really get to know those we see as “others.” How we interact with and think of those we are not around is based on stereotypes, conjecture, and representations in mass media – including television and movies. It creates a false picture of those communities.

When individuals have little to no real exposure to other groups, those handful of experiences create an image that is hard to see beyond. We use those very limited interactions to paint a picture of all of “those people.”

Many assume that all central city residential neighborhoods are a danger zone because of how the news media reports crime. We do not notice the significant drop in crime that has taken place in the past few decades. The stories about a drop in crime are not as impactful on ratings as reporting acts of violent crime on the local news.

This is not to imply that these neighborhoods are completely safe. No one knows the danger of some communities more than the residents who deal with it during their daily lives. But they also know of the great people in their communities as well. They are exposed to the good as well as the bad, unlike those outside of those neighborhoods who assume the worse because they rarely hear the positive stories.

It is so much harder to hear about the positive things going on in Milwaukee’s black and Latino neighborhoods, because we are bombarded constantly with the negatives.

As a result, the assumption is that little or no good things are happening in those places. High poverty comes with a multitude of negative consequences. However, not everyone is impacted in the same way. There are families that are doing well despite being poor. A significant number of children are doing well in school and could do more with additional resources.

Our young people are often painted with a broad negative brush, and that it is inaccurate. From my own experience, I taught middle and high school students for eight years. I am really proud of how well most of the students I worked with performed in school. There will always be students who do poorly in school for a variety of reasons. Being poor does not equate with being a bad person. Many are able to overcome economic barriers and excel. We must do a better job of accentuating the positives within the poor black and Latino communities in our city.

Occupying segregated spaces makes it very difficult for us to understand the realities of those in the places we are unfamiliar with. The concentrated poverty, caused by the loss of over 92,000 manufacturing jobs in the city of Milwaukee between 1963 and 2009, is blamed on residents who supposedly are lazy and do not want to work.

The residents of the 53206 zip code, where I grew up, have suffered more than most. The job losses have destroyed the opportunities of young and old alike. As more of those high paying manufacturing jobs left and went to the suburbs in the 1970’s, and to the ex-urban counties since then before going out of the country, Milwaukee has failed to keep people employed in family supporting jobs.

The lack of opportunity is blamed on the residents of the once thriving “machine shop” of America. None of those residents in the central city are responsible for A.O. Smith, Pabst and Schiltz Brewing, AC Electronics, American Motors, Allis-Chalmers, and others for leaving Milwaukee. They are not the reason that Master Lock, and Briggs & Stratton, and Miller Brewing have downsized. They did not own or close any of the tanneries that at one time employed thousands.

The neighborhoods who now have the highest poverty rates in the city are ones that once did well because of the great job prospects. As those jobs went away, the communities have struggled significantly to adjust to the new economic reality of a city with less than 30,000 manufacturing jobs versus, the nearly 120,000 that it had in 1963.

Because the narrative is that the poverty in Milwaukee is the fault of supposedly irresponsible, uneducated, and lazy people, those in the ring of communities doing well have no sympathy or empathy for those in the central city.

The same standard has never applied to the rural, nearly all-white communities around the state when their jobs went away. No one blamed those residents for their condition. The largely black and brown communities in Milwaukee are always judged differently.

Some espouse this misguided idea of a “culture of poverty” which was popular in the 1970’s to describe inner city neighborhoods. According to this theory, the behavior of the residents was the cause of their dysfunctional neighborhood. Never mind the lack of accountability of the city leaders who sat back and dismantled the infrastructure by refusing to invest in schools, and businesses in those places.

The condition of the people in the central city of Milwaukee, particularly blacks, has deteriorated since the early 1970’s when my family moved here. Blacks were doing really well in 1970. They had one of the highest median family income levels among blacks in the country. The poverty rate was significantly lower than the poverty rate for blacks nationwide. Our neighborhoods were safe and the residents could support corner mom and pop entrepreneurs.

By 2000, there had been a complete reversal of fortunes within the city for blacks. Our median family incomes were one of the lowest among large cities, our poverty rate was the highest in the country, unemployment was ravaging the masses, and thousands of black men had spent time incarcerated.

The city did not look like the Milwaukee of my childhood. I could not be mad at the residents. I felt they had been let down by the business and elected leadership of the city. Promises had been made and broken on numerous occasions, related to employment and transportation assistance, to reach the growing job markets of the suburbs.

Yet as I looked at the city from this lens, I noticed that those in the predominantly white suburban and ex-urban communities saw it differently. They know little of the history, and seem to be uncaring about what happened to the black and Latino community in Milwaukee.

There was little to no empathy for those residents. I wanted to know why.

I discovered a concept know as Alexithymia. Professors Joe Feagin and Hernan Vera developed the theory to describe what they defined as an inability to understand the emotions of, and empathize with others.

They also expanded this to include what they called Social Alexithymia. This is a reduced ability to understand or relate to the emotions, such as recurring pain, of those targeted by oppression. These two concepts describe the attitudes toward the black and brown residents of Milwaukee that I hear on certain talk radio shows. It also informs the rationality of racial animus shown by some fairly recent incidents at local schools.

As black parents have moved to suburban cities to look for better opportunities, their children have suffered bullying, and harassment from their white schoolmates. Although incidents of racism in our schools are spoken of as isolated incidents, the sometimes toxic racial environments cannot be overlooked.

Despite laws that were designed to prevent racial discrimination in housing, the problems persist. The communities that form a ring around Milwaukee look nothing like the city. The attempts by people of color to “integrate” have been met by rude, obnoxious, and outwardly combative white neighbors in some cases. We have made little progress in creating welcoming communities in the suburbs, despite rhetoric to the contrary. Public policies, by many cities in the suburbs, have placed additional barriers to integration in the way of building more racially diverse communities.

Building better racial relations is hard work. It requires a broader understanding of the history which we are all connected to. Decades of federal government, real estate, and banking policies created and maintained segregation. We cannot now magically make it disappear.

Negative attitudes towards black and Hispanic people helped make segregation seem like the right thing to do for whites to “protect” their neighborhoods from what the federal government described as “infiltration of inharmonious racial groups.” Those completely white communities that developed over the decades of the 1920’s through the 1960’s are still mostly white to this day.

How have the laws which made residential segregation changed the hearts and minds of whites? Are they that much more open to having black and brown neighbors? It appears to me that, based on the numbers, they certainly are not throughout our metropolitan area.

How do we change this?

I think change is already occurring. A lot of people from places like Wauwatosa, and Waukesha among others, have expressed a desire to me of wanting to live in more diverse neighborhoods. The next step in the process is to begin to understand that many black and Latino residents like living in Milwaukee and do not necessarily want to move to the “burbs.” Instead, they want for those with the power, influence, and resources to reach out and help make their neighborhoods economically viable again. This will allow the neighborhood to become safer and more like the ones I grew up in as a child.

These neighborhoods can then become more racially diverse. What then happens is that people will begin to develop real friendships and relationships across racial lines. Empathy will then develop, and people will have a real understanding of why our most challenging neighborhoods and their residents struggle.

I am not talking about gentrification, where poor black and brown residents are replaced by whites, and then moved further away from the central city. Those communities are not necessarily what is best for all of the residents. Eventually gentrification leads to re-segregated neighborhoods. We have seen this in the Brewers Hill and Riverwest neighborhoods.

We need to develop policies that allow the current residents to not be forced to flee to the northwest side of town, far away from neighbors that they knew and cared about.

Healthy, thriving neighborhoods can be developed in black and brown communities if we have the courage and make the effort to accomplish it.

When I grew up, 53206 was not a zip code that came with negative disclaimers attached to it. It was a great place to live because people were working in high quality jobs and supporting their families well. Poverty was assuredly there, but not as obvious or concentrated as it is today.

Even though not everyone was doing well financially, most families were surviving. It set the example for us children to follow. Building those types of communities helps to form the empathy required to create a more vibrant central city in Milwaukee.

Empathy cannot be built from a distance. We must get up close and personal for real positive changes to occur.

© Photo

Stefano Ravalli