The Pabst Mansion is currently seeking permission from the City of Milwaukee’s Historic Preservation Commission to deconstruct and preserve its 1893 terracotta pavilion. While a decision is not expected until a May 1 meeting, the complex process of digitally documenting the structure is already underway.

Built with terracotta as a temporary interior structure for the World Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, the pavilion was added to the Pabst Mansion as an auxiliary airing porch in 1895. Italian for “baked earth,” terracotta has been used by artisans and architects in everything from cookware to the ornate facades of Cathedrals for centuries.

Before repairs or any form of preservation can begin, the terracotta pavilion must first be deconstructed. While it has been moved and altered over the past 130 years, improper care and faulty engineering have made its parts more fragile. That condition has also made taking it apart a more complicated project, and why the Pabst Mansion reached out for help.

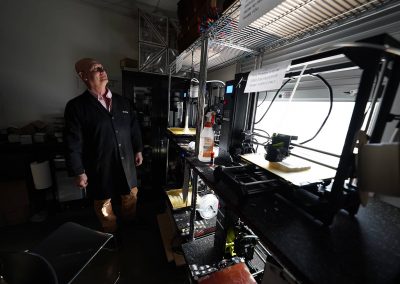

That assistance was found locally, from the world-class Historic Preservation Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s School of Architecture & Urban Planning. With titles that include Instrument Shop Manager, Building Chair, Historic Preservation Institute – Director of Documentation, and Research Director, UWM-SARUP’s William Krueger has led the effort to document the pavilion.

“It is very durable. Terracotta was one of the earliest man-made building products, for bricks or roof tiles. And one big advantage is in weight. Decorative elements can be made from stone, but they will be significantly heavier,” said Krueger. “It can last for a very long time if it is maintained properly. Usually what fails is not the terracotta itself, but the connectors holding it in place. They start to rust, or water gets behind it and starts pushing things around.”

The Historic Preservation Institute at SARUP is dedicated to the preservation and adaptive reuse of historic buildings and environments. Its lab gives students the chance to gain hands-on experience in the field of preservation.

“The Historic Preservation Institute is really unique. Usually, universities and places of higher learning are focused on the theoretical world. We are meant to bridge that gap between the professional world and the study world. Our work takes abstract conceptualizing into the reality of business,” said Matthew Jarosz, Director of the Historic Preservation Institute. “So we can work closely with contractors, using our scanning equipment to provide them with detailed documentation. UW-Milwaukee also has a series of companies that support our operations, because they see our value and expertise for their business – and in the growing trend to save existing buildings.”

Among its objectives, the Historic Preservation Institute is focused on community service projects that have been an effective way to engage students in actual preservation work. The ability to overlap academic studies with real-world circumstances has proven beneficial to both the students and the community.

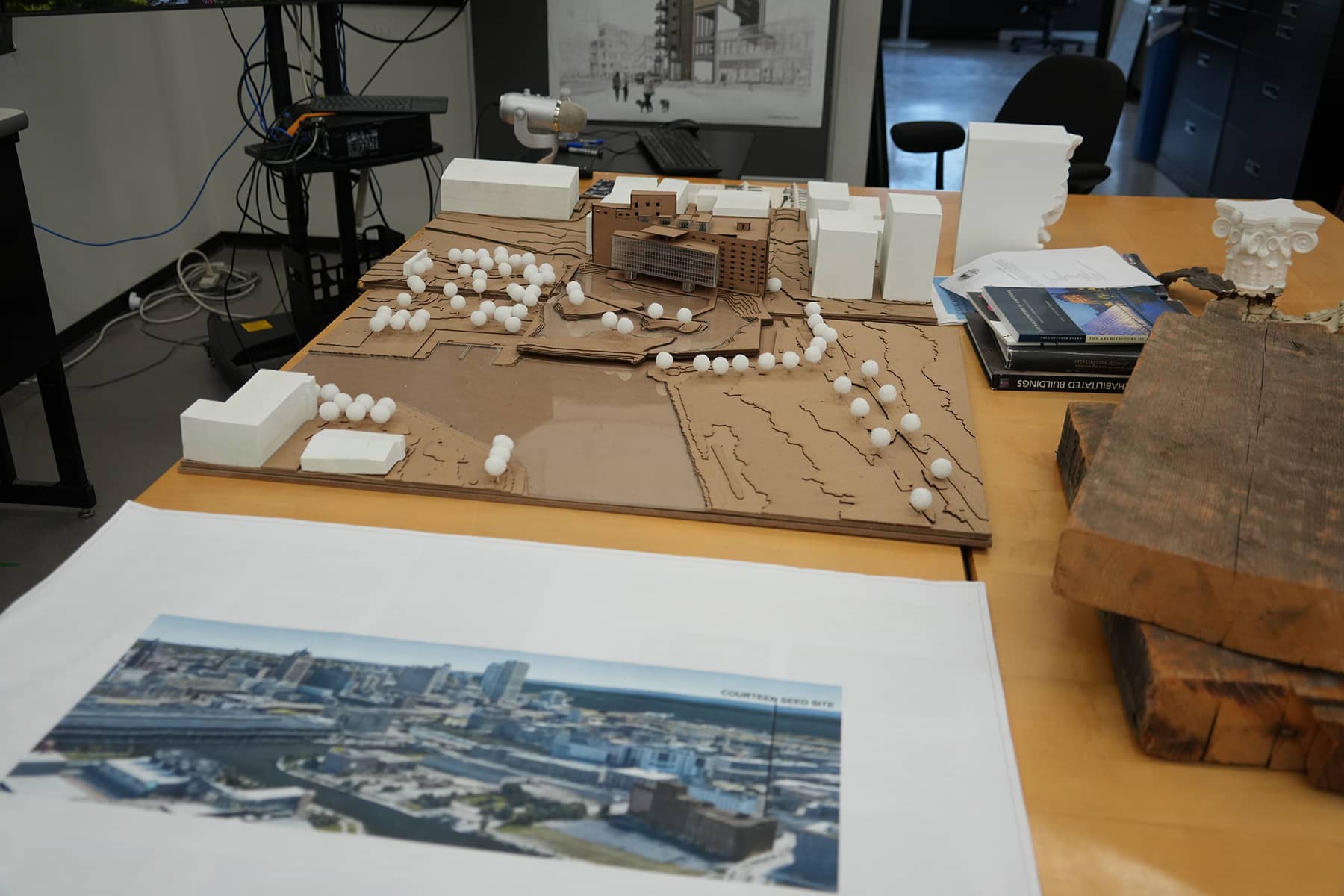

“I thought that the Pabst Mansion, and specifically the pavilion, would be a great exercise for our students,” said Krueger. “We sent them out to do some documenting and scanning, and label each and every piece. Then they would turn around and use that material to produce really detailed 2D drawings so we have a map. Hundreds of pieces have been recorded, and we know where each one goes.”

The studio was sponsored by Gladding McBean, a terracotta manufacturer on the West Coast and one of the last two major manufacturers in the United States. Established in 1875, its original product was clay sewer pipe. By 1883, the company had evolved into a major manufacturer of architectural terracotta.

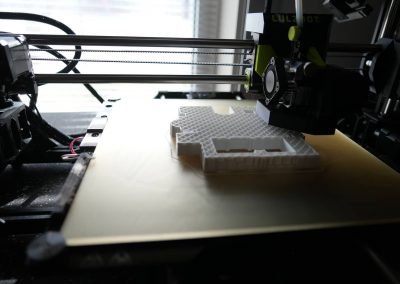

“Gladding McBean gave us the money to run the studio to try and reinvent terracotta. So when the studio started, we were exploring paths to a new level of preservation when we got connected with the Pabst Mansion for the pavilion project,” said Krueger. “The technologies to scan and document objects in the studio include cutting-edge LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), photogrammetry, and drones. Those methods also allow for individual pieces to be documented in the field without pulling them off. A digital model can then be made and archived of every single object in virtual reality. From that we can reverse-engineer the pavilion.”

The traditional workflow of terracotta documentation and restoration meant a selection would be removed from a building, put on a truck, and shipped to one of two facilities in America. Once there, artisans and draftsmen would measure it and redraw it with the same methods and techniques used for hundreds of years. Because terracotta shrinks when it is made, a replacement mold would be handcrafted about 10% larger.

But with laser scanning and photogrammetry, UWM-SARUP can document it in a virtual environment. Then, a mold can be enlarged digitally, and be basically printed with the click of a button. Instead of pulling a piece off the pavilion and shipping it across the country, students can scan it in place.

The process saves a considerable amount of time and money, while achieving a nearly identical result to traditional methods. It is using new technology, but with the ancient art of the mind.

“Sometimes the notion of preservation is not clearly defined, since a structure can evolve over decades. Some historic buildings lose their pieces and parts, essentially their integrity gets lost over time. And with that also goes an important component of community support to save them,” said Jarosz. “The way this has taken off in recent years, preservation has moved beyond just an emotional appeal to keep a historic building because of connections to the past. It is good stewardship. And it really starts to hit home with developers about how it affects the fabric of our cities.”

Jarosz added that there is already a great deal of buried energy within these vintage buildings that still exist. That condition is finally being taken into account. In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, the industry just considered them outdated. To make way for new structures, it was thought necessary for society to get rid of everything old.

According to a recent 2022 survey by the American Institute of Architects (AIA), architecture firms earned more from renovations than from new builds for the first time in history. That trend showed a new awareness, to take control of the energies already spent and to use them wisely, rather than just leveling buildings and starting over again.

“It is very important that students, and the public, understand how valuable our existing structures are. New is not always better. All the work and effort and energy that went into making any building, right, wrong, or otherwise, it is still there. If you can preserve or conserve that building and reuse it, you are saving money and energy. The planet only has so many resources it can give,” said Krueger. “We have to use everything very wisely and make intelligent decisions about how we deconstruct or conserve things. And in this case, with the Pabst Mansion’s pavilion, it is a part of Milwaukee’s identity and legacy.”

The Historic Preservation Institute shows students that there is work in preservation careers. Even a lot of modern buildings need maintenance to protect them over time. And as new buildings go up, before the walls are covered, they are scanned. Virtual models can then be made of different stages of construction to assist in future modification or restoration.

“I believe modernism hurt the terracotta industry, because there was a minimalist design philosophy that did not need or want a decorative aesthetic. But some of that is starting to come back, and that is what we are exploring in this studio. Not just restoration, conservation, preservation, and archiving, but also designing new buildings,” added Krueger. “Sometimes we even explore how to re-skin modern buildings with terracotta.”

- Pabst Around Milwaukee: Illustrated map details vast reach of Captain Frederick Pabst beyond his brewery

- “Seeing the Universe in a Single Flower” at a Japanese Ikebana exhibit inspired by the Pabst Mansion

- Pabst Mansion creates new leadership position to address challenges and opportunities

- Pabst Mansion to co-host first “Evening Fit for a Baron” in more than 30 years

- Pabst Mansion decks the halls for Christmas Twilight Tours

- Pabst Mansion celebrates 125 years with open house and family reunion

- Photo Essay: Pabst and Gettelman Family attend Baron Brunch

- Photo Essay: Pabst for Paws

- Pabst donations on 180th birthday honor animal charity

- Video: A look inside the Pabst Mansion

Lee Matz