For more than 170 years, the congregation of Summerfield United Methodist Church served as a moral anchor on Milwaukee’s east side. Founded in 1852 by abolitionists, it was sustained through eras of reform and remembered as the birthplace of Goodwill Industries. Since 1904, its Gothic Revival building at Cass and Juneau has stood as a visual landmark and a center for compassion-based outreach. This editorial series revisits Summerfield’s legacy on the second anniversary of its final service, held June 25, 2023.

In a city with deep industrial roots and immigrant memory, one church stood as a moral compass through eras of war, division, and reform. Summerfield United Methodist Church did not just open its doors in 1852, it opened them to the fugitive, the laborer, the widow, the immigrant, and the dream of justice that outlived its brick and mortar.

Its origin was not grand. The church began as a mission of Milwaukee’s Spring Street Methodist Episcopal Church, aimed at the growing number of residents on the city’s east side. The Rev. S.C. Thomas, a man of deep organizational vision, saw spiritual need in the neighborhood and acted swiftly.

He purchased the abandoned Universalist Church building for $400 and had it hauled to a lot on Jackson Street. The first service in that humble structure was held on December 1, 1852.

But Summerfield’s mission quickly grew beyond worship. In 1854, only two years after its founding, members of the church joined abolitionist Sherman Booth in a defiant raid on the Milwaukee jail to free Joshua Glover, an escaped enslaved man from Missouri who had been captured under the Fugitive Slave Act.

The church’s complicity in breaking federal law to defend human freedom was more than a political act, it was a theological one. This was a church that understood justice as a sacred duty.

By 1857, the congregation had relocated to the northwest corner of Van Buren and Biddle streets and renamed itself “Summerfield” in honor of Rev. John Summerfield, a Methodist preacher whose passion for revival swept the eastern United States and Ireland before his early death at 28.

The new church building was an ambitious project, with tall brick walls and a planned steeple that would make it one of Milwaukee’s most prominent landmarks.

But disaster came early. The financial Panic of 1857 left the congregation unable to meet its pledges. Only $3,000 of the pledged $12,000 had come in. The mortgage was foreclosed, and it could have ended there.

Instead, the congregation fought back. Members took on sewing jobs, addressed envelopes for Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance, sold vegetables door-to-door, anything to raise funds. Women left their homes on the fashionable east side and labored alongside working-class women to save their church. Slowly, they paid off the debt. Summerfield remained open.

Leadership during those early years was exceptional. The Rev. Samuel Fallows, appointed pastor in 1865, had served in the Civil War as a Union officer and would eventually be promoted to Brigadier General.

Under his leadership, the church championed the welfare of veterans and became a hub for what would later grow into the Soldiers’ Home, the earliest model of federal veteran care in the country, shaped in part by his wife Lucy’s work with the Soldiers’ Aid Society.

Summerfield’s role in progressive action did not stop with the war. In 1869, it launched Milwaukee’s first Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society, the second in the United States. This early foundation of what would become the United Methodist Women was led by Fannie Hooley McChesney, whose passion for global service inspired decades of activism.

The church was a pioneer in practical service as well. In 1883, member Mrs. R.W. Patterson founded the Protestant Home for the Aged, now known as the Milwaukee Protestant Home, on Van Buren Street.

It was one of the earliest elder care facilities of its kind in the city and came at a time when institutional support for aging women was nearly nonexistent. Her daughter, Amelia Patterson, would later dedicate her life to church work and become a resident of the home she helped inspire.

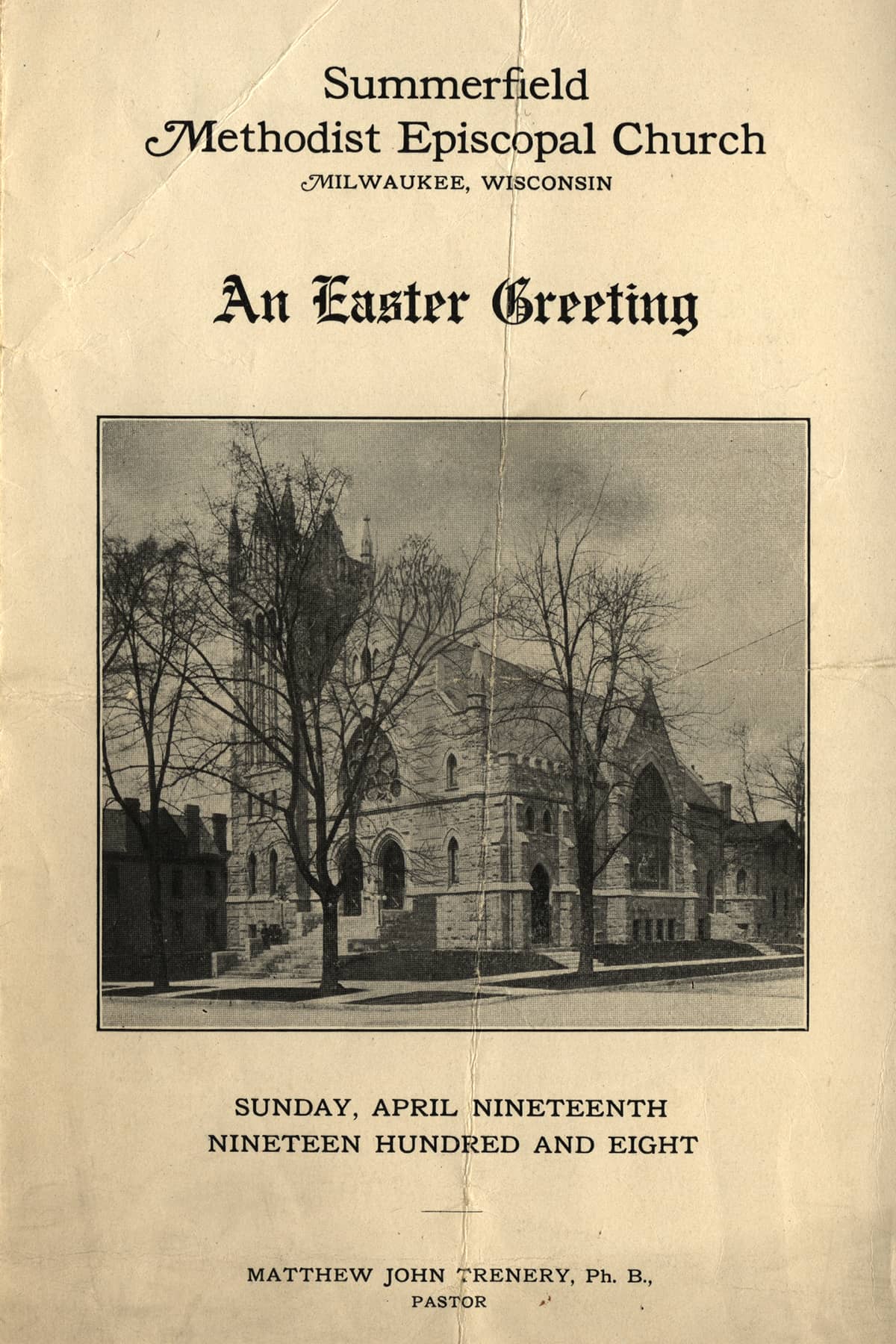

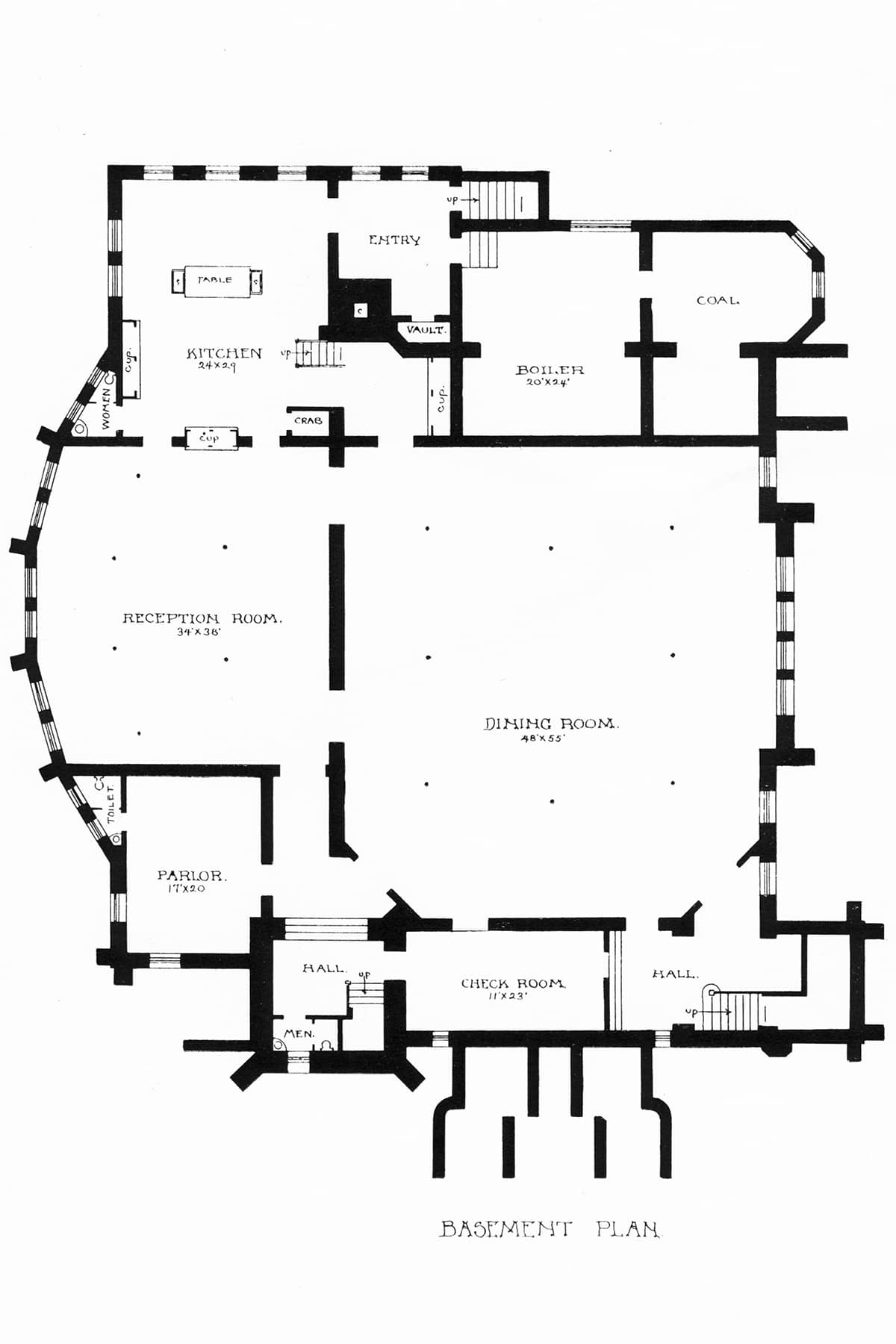

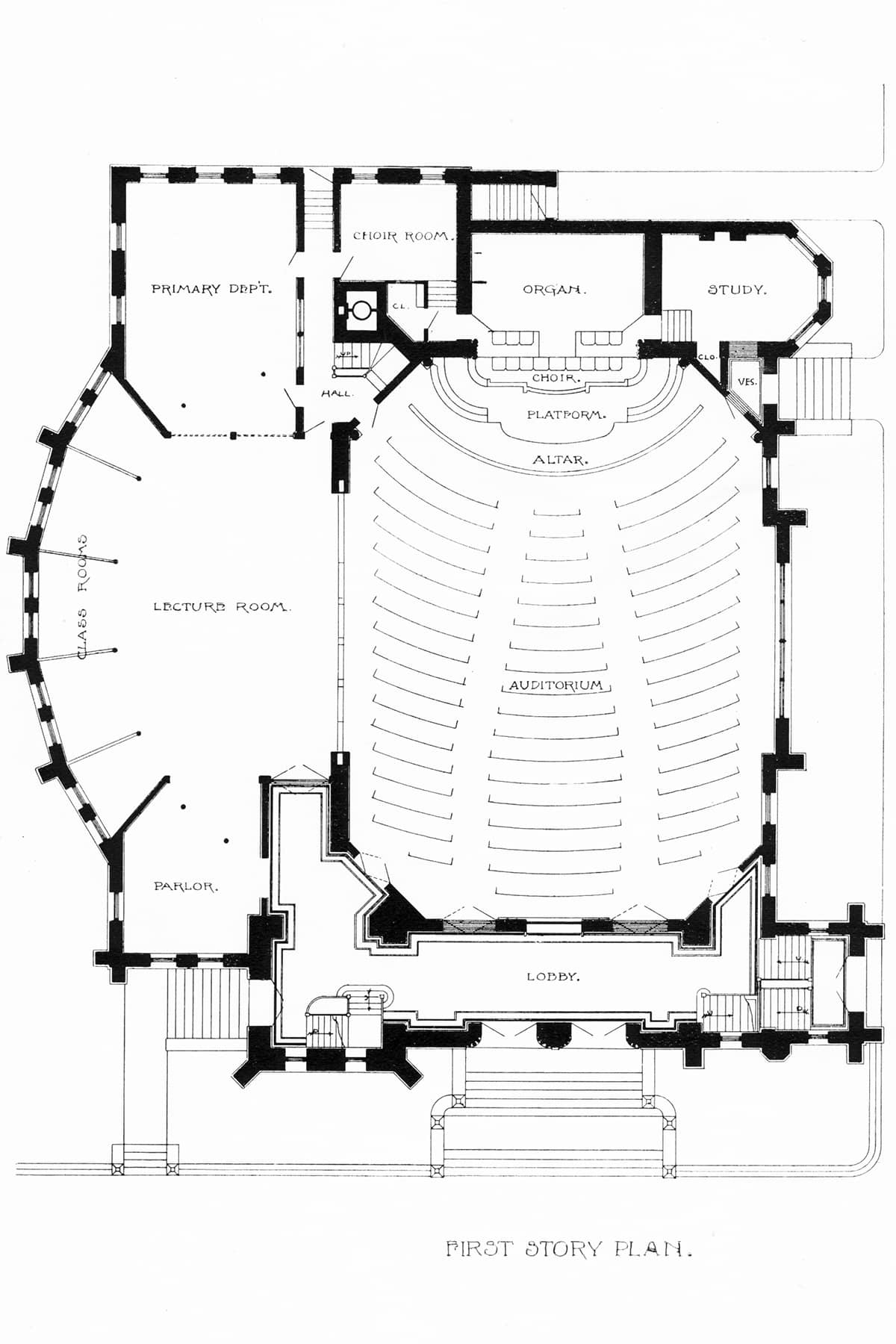

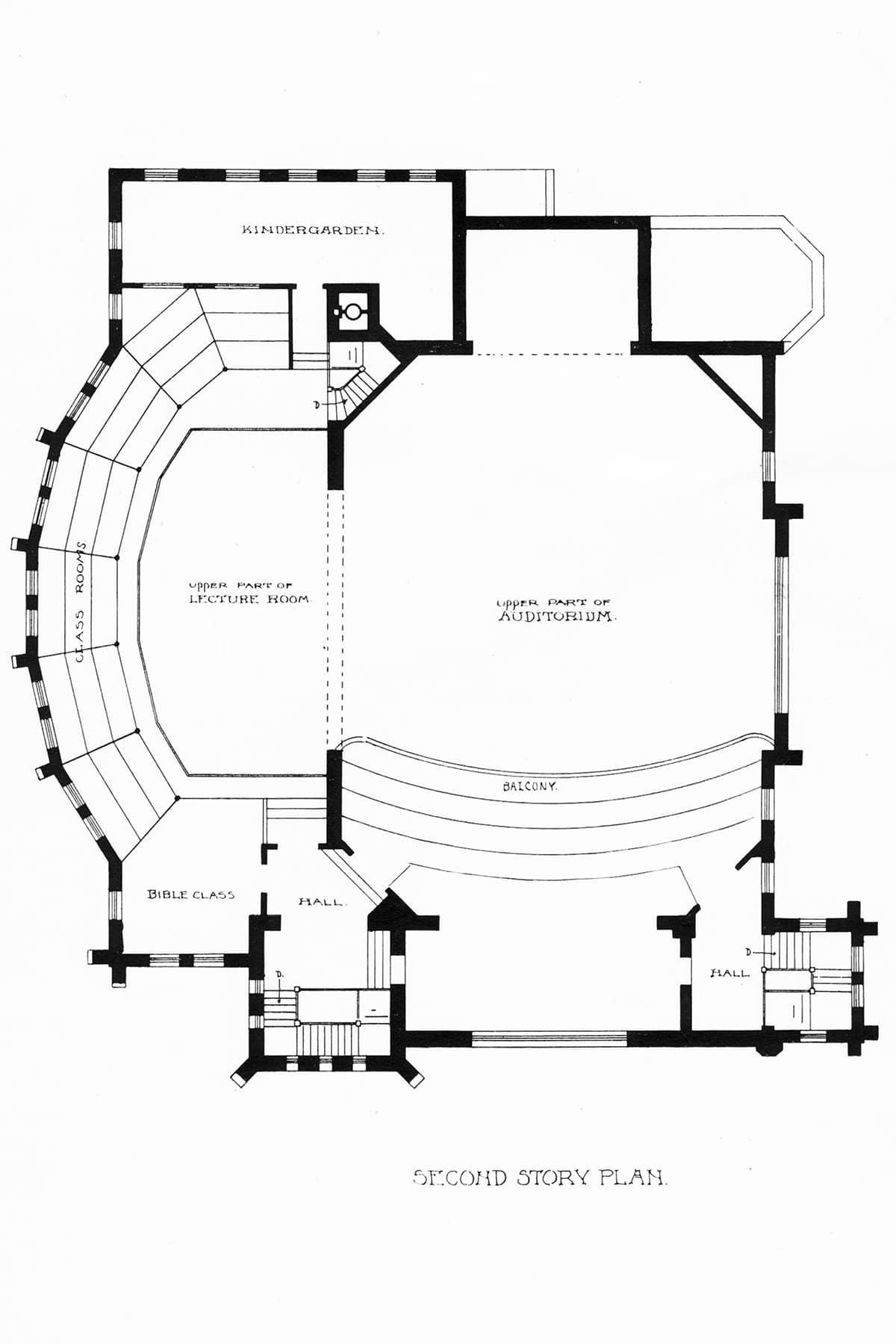

As Milwaukee changed, so did Summerfield. By the early 1900s, with the east side shifting from elite mansions to urban flats, the church moved again, this time to Cass and Juneau. Under the leadership of Rev. Sherman P. Young, the new structure was built in 1904, incorporating stained glass windows salvaged from the original 1856 church. Those colorful medallions exist as historic treasures and some of the oldest preserved stained glass in Wisconsin.

The sanctuary’s Nativity Window, a tribute to the Elmore family, remains one of the most visually striking features of the building today. Decades of tradition saw Milwaukee families stand outside it in the snows of late December and sing Christmas carols under his kaleidoscopic illumination.

By the 20th century, Summerfield was no longer just a neighborhood parish, it was a cradle for institutional reform. In 1919, after visiting Boston to learn about their employment ministries, Summerfield’s adult Sunday school class founded Milwaukee’s branch of Goodwill Industries in the church basement. The program provided jobs, training, and dignity to thousands of struggling residents. It remains one of the church’s most enduring legacies.

Summerfield’s influence rippled outward, not through numbers, but through lives transformed by its presence. The sanctuary on Cass Street, finished in 1904, became more than just a worship space. It was a neighborhood anchor, a social engine, and an incubator of compassion.

Through the 20th century, the church’s commitment to serving the vulnerable remained constant. Summerfield was instrumental in hosting early youth groups, organizing citywide choir programs, and creating safe social spaces for working-class families. At a time when many congregations turned inward, Summerfield looked out, opening its parlor and fellowship halls to immigrant communities, mission groups, and the displaced.

By the 1930s, Summerfield absorbed the Immanuel Methodist Church, a historically German congregation from Milwaukee’s north side, as part of a broader effort to consolidate and preserve shrinking ethnic parishes.

It was not the first merger, and it would not be the last. In 1968, following the national merger of the Evangelical United Brethren and Methodist churches, Summerfield absorbed its EUB sister church on Astor Street, symbolically uniting parallel legacies under one roof.

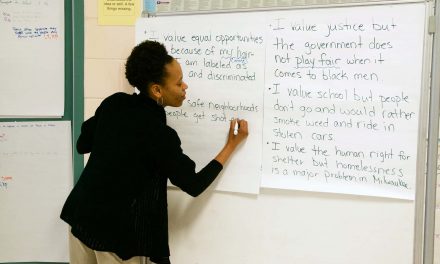

While denominational consolidation helped preserve its identity, Summerfield’s mission increasingly returned to its grassroots. During the Civil Rights era and into the late 20th century, the church supported open housing initiatives, neighborhood advocacy, and partnered with social agencies working to combat poverty in Milwaukee’s east side and downtown.

Into the 2000s, despite dwindling numbers, the congregation never turned away from its ethic of inclusion. In 2014, when Iglesia Metodista Unida: Ministerio Hispano Fe, a Spanish-language United Methodist congregation, was without a building, Summerfield offered them sanctuary. For several years, the church housed their Sunday worship and weekday prayer groups. To the Hispanic families who gathered in those pews, Summerfield was also a home.

As the congregation aged, new programs tried to meet changing needs. The “Open Doors” initiative welcomed isolated seniors to community lunches. The weekly Meal Outreach program, launched in 2011, served food to the unhoused and underemployed. From the same basement where Goodwill was born a century earlier, volunteers handed out warm meals and dignity.

That same year, Summerfield celebrated its 150th anniversary, a milestone for any Milwaukee institution, let alone a church that had migrated across two buildings, weathered financial collapse, and outlived nearly all of its founding neighborhood institutions.

Still, the signs of strain were evident. Attendance waned. Deferred maintenance piled up. By the late 2010s, Summerfield was no longer a congregation in growth. It was a congregation in resistance, doing its best to outlast a culture that increasingly left churches behind.

There were revitalization efforts, but the historic sanctuary grew harder to sustain. Though still loved by members and remembered by generations, the future was uncertain. The building, with its surviving stained glass medallions rescued by Dr. Stansell in 1940, remained a visual gem. The spirit inside, however, belonged to an era whose time was closing.

What Summerfield offered was never spectacle. Its ministers did not build empires. Its members did not chase wealth. But from the abolition of slavery to the founding of social institutions, its legacy is written into the city’s moral architecture.

Even as its pews emptied, the echoes remained. It could be heard in the hymns sung in German and Spanish, the folded letters sent to soldiers overseas, the whispered prayers for strangers at the door.

Summerfield United Methodist Church may have begun as a mission for East Side Methodists, but it became a mission for Milwaukee itself. And that mission, like the light through its century-old stained glass, endures beyond stone or steeple.

- Faith Identity: What the “traditionalist denomination” split means for a Methodist Church in Milwaukee

- Construction Sunday: Milwaukee’s church renaissance and the process of renovation at Summerfield

- A Hand Up, Not a Hand Out: 100 years of Milwaukee’s Goodwill began in the basement of Summerfield

- William H. Metcalf: Iconic pictures of 1870s Japan were taken by an amateur Milwaukee photographer

Lee Matz

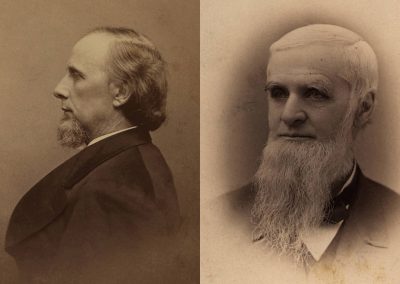

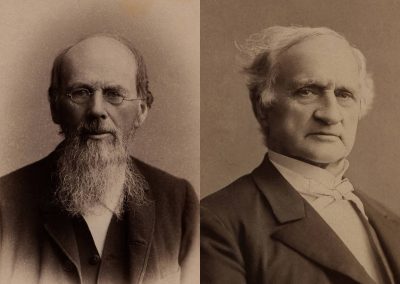

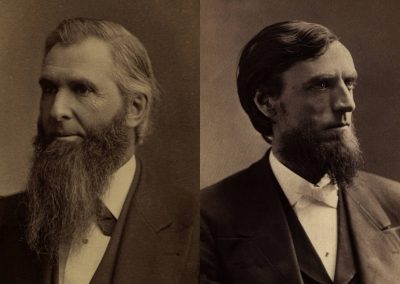

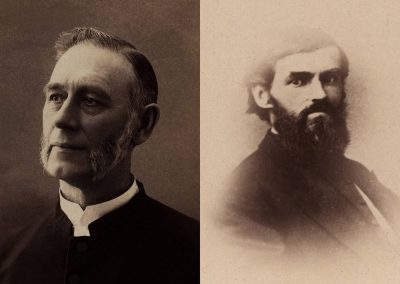

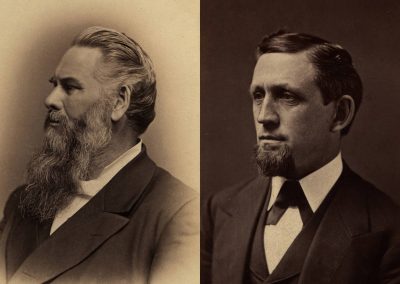

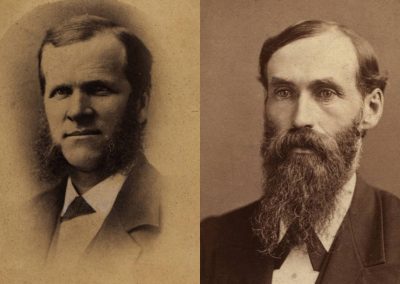

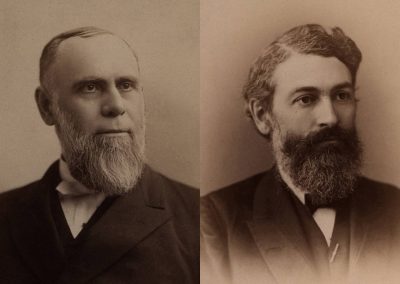

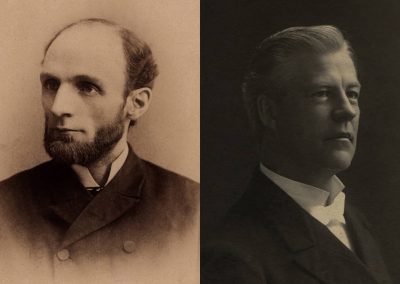

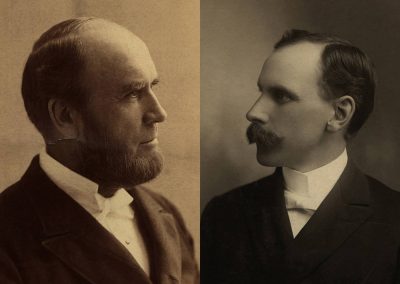

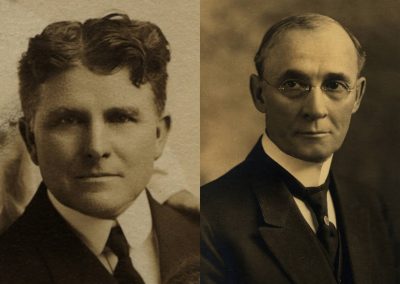

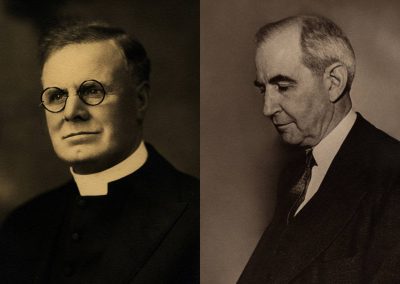

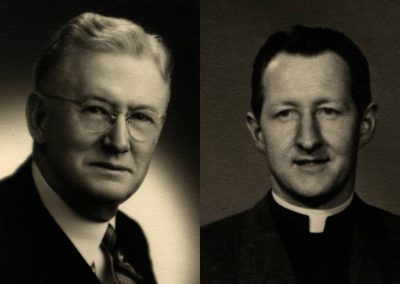

Pastors of Summerfield M.E. Church (1852 – 1952): Thomas M. Eddy, Jabez Brooks / S.C. Thomas, Edward Cooke / Phineas B. Pease, Samuel Fallows / Henry Summer White, John Hill / William Page Stowe, Oscar B. Thayer / C.F. Stowers, Samuel Newell Griffith / O.J. Cowels, James E. Gilbert / Olin A. Curtis, E.G. Updike / J.R. Creighton, O.D. Cannon / S.P. Young, Samuel H. Anderson / William Wilson, Hiram S. Witherbee / Robert B. Stansell, Norman S. Ream