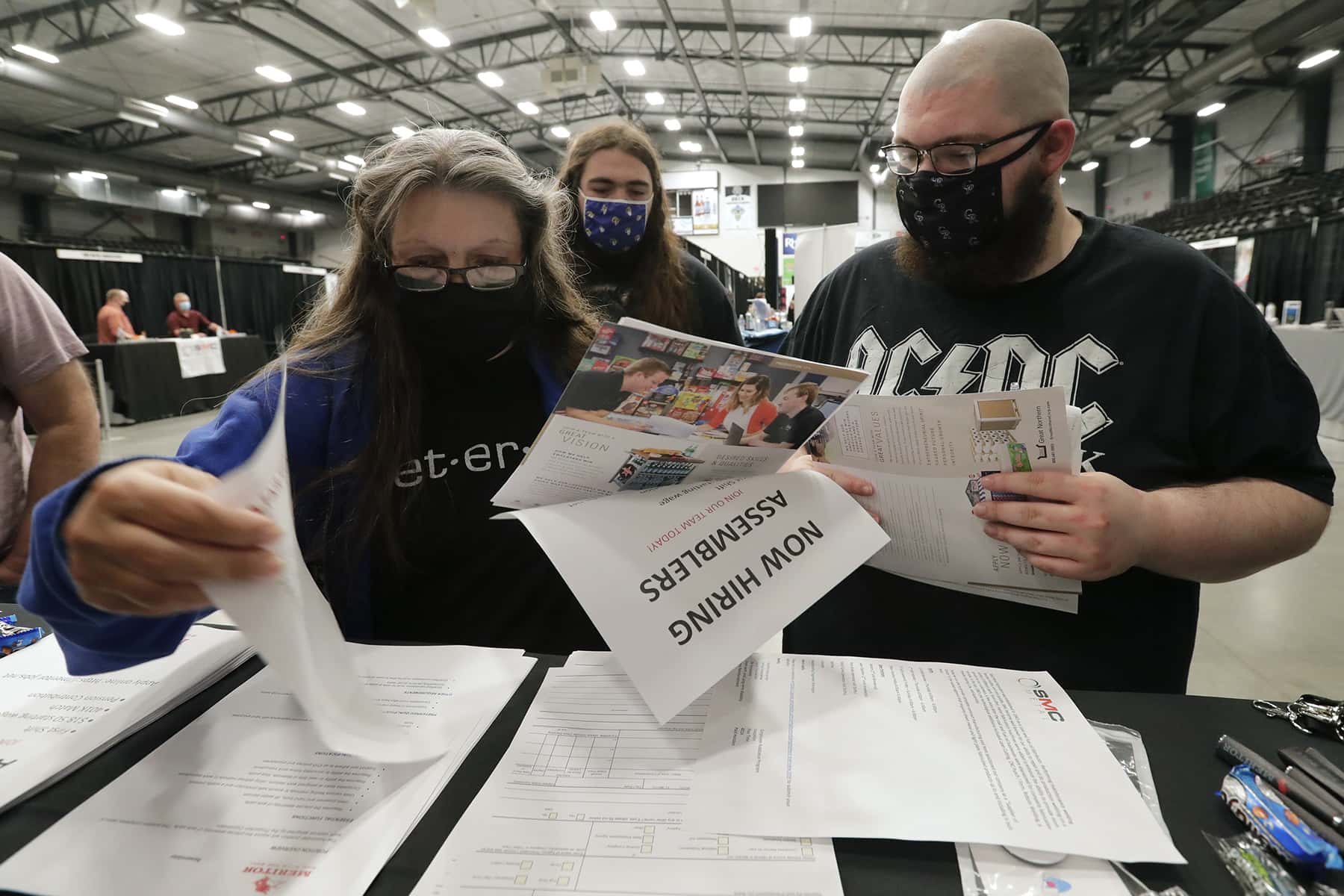

To understand how Wisconsin’s labor shortage has transformed the jobs market, look no further than an October 14 job fair to hire workers for expansions of Pierce Manufacturing’s production plants in Neenah and Fox Crossing.

The fire truck manufacturer aimed to hire 200 assemblers, welders, electricians and painters. Pierce touted competitive pay, health and well-being services and matching retirement contributions as most major employers do now, and it highlighted another incentive: $10,000 in educational reimbursement per year for employees working toward a college degree.

The company conducted interviews and drug tests on the spot, and it welcomed candidates with little experience. Becky Bartoszek, president and CEO of the Fox Cities Chamber of Commerce, said the company hired 100 people at the fair — an example of how aggressive employers must be to find talent.

The fierce competition for talent won’t end soon, and employers across industries must adapt to survive the statewide worker shortage, northeastern Wisconsin workforce experts said. Until then, residents must continue to live with the impacts of a tight labor market: Store and restaurant closures, supply shortages and longer wait times.

Thousands of jobs are going unfilled due to longstanding demographic trends and workers’ changing expectations about benefits, pay, hours and workplace culture.

That means employers must rethink recruitment. It won’t be easy, but the stakes could not be higher, said Eric Vanden Heuvel, vice president of talent and education with the Greater Green Bay Chamber, during a recent workforce panel discussion at the University of Wisconsin-Green Bay convened by the USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin.

“Evolve or die,” he said. “If your business takes the approach ‘This is how we do things,’ you won’t survive.”

Here are the key questions and answers for employees, employers and communities as they navigate a tight labor market in Wisconsin, according to experts who participated in the discussion.

Is this a temporary thing?

No, it’s the acceleration of a trend that precedes the pandemic. Birth rates have steadily declined since the births of 76 million Baby Boomers between 1946 and 1964, leaving fewer workers to replace retirees. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated retirements. Vanden Heuvel expects such challenges to continue for at least a decade.

“It just results in more jobs than there are people,” he said.

What does that mean for business?

Companies must keep their benefits and salary packages competitive, seek out employee input, and collaborate regionally to meet workforce needs, especially in business sectors such as paper and other manufacturing, transportation, health care and hospitality. Vanden Heuvel said competing businesses must cooperate in areas like recruiting talent to the region. He cited school districts as an example.

“(O)rganizations are starting to come together to say ‘How can we recruit more teachers to the area?’ not ‘How can I hire the teachers that I need?’ ” he said.

Employers must recognize the modern workforce’s concept of a job and work-life balance differs from the Boomers’ post-Great Depression mentality that you find a job, feel fortunate and stay put until retirement, Vanden Heuvel said.

Bartoszek said successful companies will be those where workers want to work, not have to work.

What does that evolution look like?

Experts say that successful employers will focus on cultivating a good work culture and being flexible with employees. For example, manufacturers should look at hiring part-time workers, something many employers have been hesitant to do in the past, said Ann Franz, executive director of the NEW Manufacturing Alliance.

A manufacturing alliance study of 200-plus people between the ages of 56 and 65 found that flexible hours keep people in the workforce longer, Franz said. Similarly, younger workers often cite work-life balance as an important factor when picking a job.

Chambers, regional economic development agencies and some employers also have seen success traveling to talent, rather than waiting for it to come to them.

Bartoszek cited a recent recruiting trip to Michigan Technological University. Rather than the standard spongy footballs or pens to hand out, the Fox Cities Chamber and employers parked a Pierce fire engine and other equipment on the campus, grilled burgers and gave away T-shirts to anyone who talked to an employer about jobs.

Graduating students have repeatedly told chamber officials and recruiters on such trips that the specific job didn’t matter as much as a community’s amenities and quality of life. This trip was no different. The event drew 600 students, eclipsing the university’s goal of 150.

What does that mean for employees?

Employees have more options and greater bargaining power when it comes to finding a job. This is the first time in decades that employees “have the upper hand,” said Allen Huffcutt, an associate professor of management at UW-Green Bay’s Cofrin School of Business.

“They feel empowered, like they’re not helpless,” he said. “They can be proactive and change things.”

In September, a record-breaking 4.4 million people quit their jobs, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the United States is seeing an uptick in workers going on strike.

“Employees are in a position where you don’t have to stay in a job you’re not happy in,” Bartoszek said.

She recommends people looking for a new position seek out companies that offer the benefits that are most important to them, such as tuition reimbursement, remote work opportunities or paid time off, for example.

“Tear down your preconceived barriers about what you can and cannot do, especially around job requirements,” Vanden Heuvel said. “The concept that this job wants five years experience and you need to have this degree and this background, those are oftentimes self-limiting beliefs.”

Are sign-on bonuses or incentives making a difference? No. Experts say they only encourage employee churn at a time of low unemployment and workforce engagement at levels near its pre-pandemic high.

Wisconsin’s September labor force participation rate was 66.6%, higher than the national rate of 61.6% and up from 66.5% in August. The workforce participation rate measures how many people ages 16 or older are working or actively seeking work.

Wisconsin’s unemployment rate in September was 3.9%, while the national unemployment rate was 4.8%, according to the Department of Workforce Development.

The Fox Cities Chamber of Commerce does not advise businesses to offer sign-on bonuses in that environment because it “led to a new generation of job jumping,” Bartoszek said. Some workers will try out a job for six months and then jump to the next one for the bonus, she said.

Instead, experts suggested focusing on incentives like tuition assistance for immediate family members, flexible schedules, opportunities to advance and assistance with basic needs like child care.

What would bring more people into the workforce?

Employers and communities must address issues like access to child care, affordable housing and transportation to bolster the pool of workers. Ariens Co.’s partnership with KinderCare to open a child care facility in August for workers in Brillion is a great example of how larger manufacturers are answering workers’ needs, Franz said. However, not every business can undertake such an expense.

Bartoszek said employers have partnered with chambers of commerce or other businesses interested in expanding access to child care. Additionally, employers must connect with historically underemployed populations that can fill the demand for jobs: people with disabilities, people with criminal records, retirees, people for whom English is a second language and people of color.

Christina Thor, 9to5 Women Wisconsin’s state director, said a lack of access to affordable child care is among the biggest barriers to work faced by women with children, particularly women of color, according to a survey by members of the grassroots advocacy group for working women.

“If you want women here, take a look at family structure first. Take a look at their priorities first and they will come to you,” Thor said.

Thor, who became state director in October, said parents working second or third shift jobs have little or no access to child care services. She said there also is a major need in northeastern Wisconsin for child care services that are sensitive to the needs of the region’s diverse communities of color.

“Make sure (child care) is culturally competent and linguistically competent,” Thor said. “If I want my child to speak my native tongue and to know my culture and know what happens at home, that’s a better, trusting relationship and it improves overall child development.”

Franz noted there are 482,000 people in Wisconsin with disabilities, “a huge labor market we’re missing out on” and another 9,000 people exit the correctional system each year.

Craig Coleman, a Green Bay-based job developer and transition coach with Forward Service Corp., said most people leaving the corrections system want to work. The Madison-based nonprofit provides training and support service to people exiting the corrections system in 46 of the state’s 72 counties, but Coleman said communities should better support people as they return to the workforce.

He said his grant-funded job is to help returning workers get help with resumes, car repairs, training courses, child care assistance or anything else that may stand in the way of landing a well-paying job.

“If we can provide them with a family supporting wage, that’s one thing off their back that can increase their chance of being successful,” Coleman said. “Ninety-nine percent of the justice involved population are good employees. They’ve figured out what went wrong with their lives and they do not want to go back. That alone makes them good employees.”

The Bay Area Workforce Development Board, a training and job search agency that serves an 11-county region, is launching a new initiative to actively connect with historically underemployed populations, said executive director Matt Valiquette.

Valiquette recalled his own frustration looking for work after retiring from the Marine Corps a decade ago. He sent out resumes with no response. After a visit to a job center, Valiquette tweaked his resume, and soon his phone was ringing with offers.

“It was a bad feeling being 40, feeling like a failure and not knowing where to turn. How many others give up in those circumstances?” he said. “We can’t afford for them to give up.”

Natalie Brophy and Jeff Bollier

Dаn Powеrs and Wіllіаm Glаshееn

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.