By Erika M Bsumek, Associate Professor of History, The University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts and James Sidbury, Professor of History, Rice University

The effort by Democrats and Republicans in Congress to find agreement over a federal infrastructure spending bill has hinged on a number of factors, including what “infrastructure” actually is – but the debate ignores a key historical fact.

There is widespread public support for public investment in building and repairing roads and bridges, water pipes and public schools – as well as providing more elder care and expanding broadband internet access. All of those were part of President Joe Biden’s initial $2.3 trillion infrastructure plan, announced in March 2021.

Republicans criticized the plan in part because of disputes about how to pay for it all, but also by saying that its inclusion of paid sick leave, efforts to fight climate change and investments in child care and medical care were not really “infrastructure” but rather “social programs.”

A smaller plan may be passed in a new compromise agreement, but as historians, we believe it is important for Americans to understand that infrastructure investment has always involved social programming. That has inevitably meant that it benefited some and disadvantaged others. In our view, Americans have been far too hesitant to acknowledge that many infrastructure projects, whether consciously or through neglect, have hurt communities of color.

Infrastructure in American history

It is true that the most basic or traditional understanding of national infrastructure has focused on transportation. Benjamin Franklin, the nation’s first postmaster general, was at the head of a long line of policymakers and presidents to highlight the construction of roads as a way to build the nation’s economy.

They knew it was important for farmers to get goods to market and for our nation’s residents to be able to get timely news from distant locales. Passable roads helped tie the 13 Colonies together. Canal building road building and then the construction of railroads were key elements of both building the economy and the nation itself.

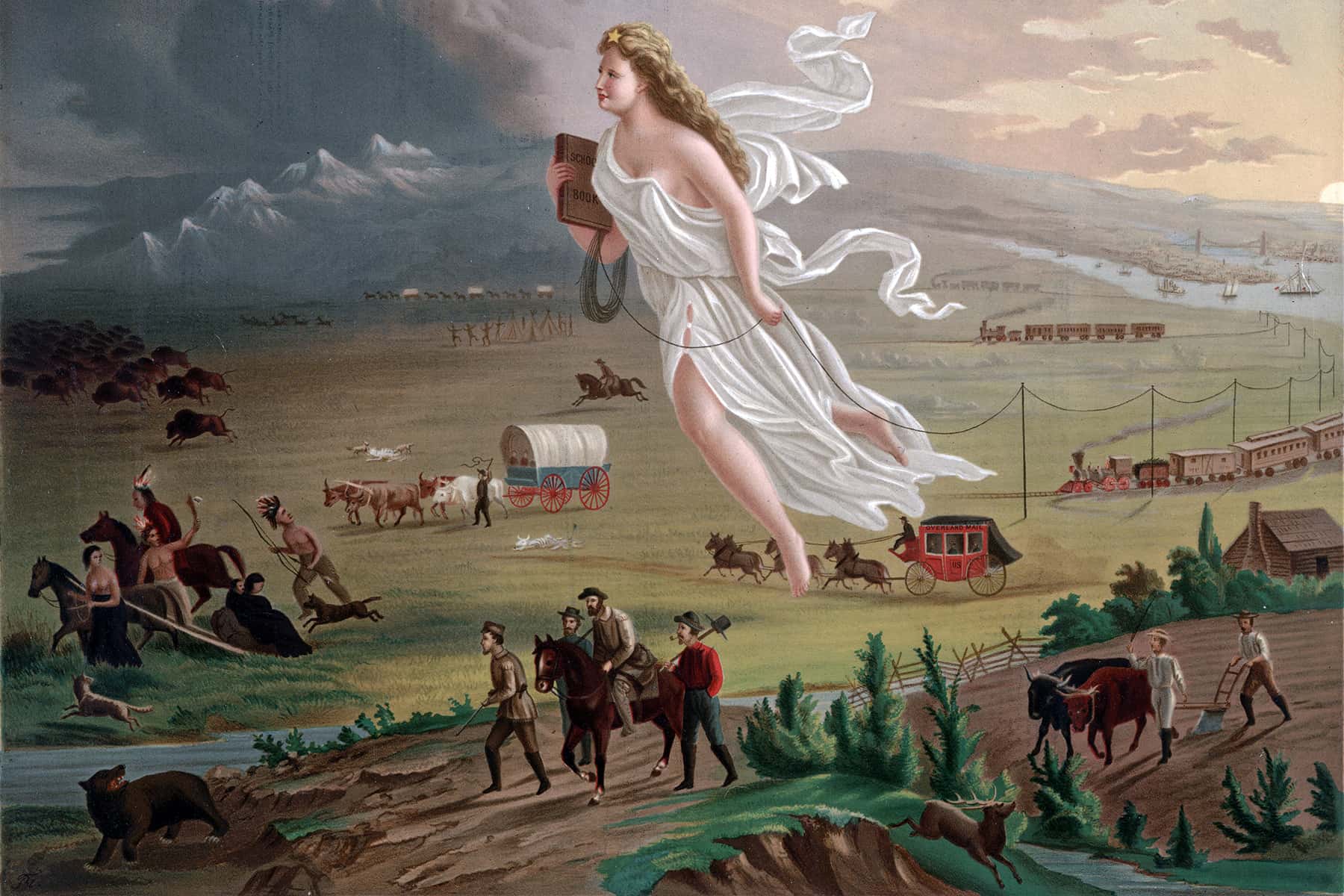

As those roads and railroads spread throughout the U.S. in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, they also carried new waves of migrants into land inhabited over millennia by Native Americans. Those migrants brought diseases and violent land seizures, pushing out Native Americans.

For example, in the 1820s, white planters moved into the land taken from the Creeks and other tribes in what is now the Deep South. Millions of enslaved African Americans who had built strong families and communities within the brutal confines of slavery were torn from their homes in the Upper South, some by planters moving to take up cotton land in the new territories, and others by slave traders who purchased enslaved people and sent them to be sold in the cotton South.

Some roads and railroad projects were aimed at displacing or removing Native Americans from their homelands as part of a larger social agenda to force them to either assimilate or “disappear” – a euphemism for cultural destruction.

Private companies received enormous public subsidies from the federal government – often in the form of Native-occupied land – to build railroads through the Plains. When they did so, they explicitly sought to exterminate bison both to prevent dangerous collisions with locomotives and to starve the Native peoples resisting Western expansion.

In 1867, the Kаnsаs Pacific Railway held bison-hunting events in which the car would slow so passengers could slaughter the large animals from their windows. That same year, an Army official famously quipped: “Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.”

Other projects may not have been intended to be so overtly malicious, but their effects were no less harmful to the societies they affected. There is no evidence, for example, that those who took land from the Creeks gave any thought to the lives of enslaved Virginians, but the resulting interstate slave trade devastated the communities that enslaved Virginians had built over the preceding century.

The infrastructure projects – the building of the roads – were intended to contribute to the nation’s economic development and to benefit white citizens who built prosperous plantations in the Mississippi Delta. They accomplished that. But they did so at enormous, and largely unacknowledged, cost to communities of color.

Infrastructure as social policy

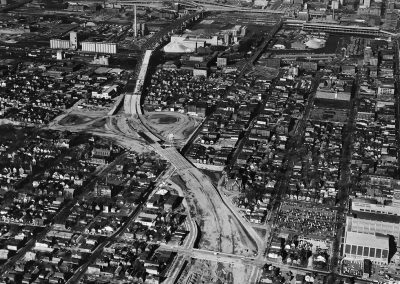

The tradition of carrying out social transformation through transportation projects – both what got funded and how it was designed – continued with the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act of 1956, which built the nation’s web of interstate highways.

The massive new roads had benefits, tying the sprawling nation more closely together. But they also divided existing communities, often in ways that exacerbated racial and class inequities. Some of those highways, such as I-26 on the Charleston peninsula in South Carolina, cut straight through or successfully isolated African American and Latino communities, and even destroyed homes and businesses to make way for pavement.

The result created “physical barriers to integration” and often worked “to physically entrench racial inequality,” as New York University law professor Deborah Archer told NPR.

Building an infrastructure of inclusion?

The history of American infrastructure development has always been linked to social development, with productive consequences for some and often-disastrous effects on others.

The compromise bill that will go before Congress is inherently both an infrastructure bill and a social policy bill, regardless of how politicians describe it. It will provide long-awaited and much-needed funds to build new roads and repair dams to foster economic development and may extend broadband to the various communities that have been left out of the digital economy. But those benefits may not come equally to Americans of all races and economic classes.

People are already attuned to how infrastructure can hurt local communities as much as it can help them. For instance, America’s biggest current environmental battle is being fought in Minnesota, where Native American activists oppose the construction of yet another fossil-fuel pipeline that threatens the waterways and ecology of the entire region.

As history shows, infrastructure simply cannot be considered separately from social programs. Trying to do so makes it less likely that leaders and society as a whole will notice, or seek to improve, the social consequences of what gets built – to those who benefit, and those at whose expense the development may come.

Library of Congress and Milwaukee County Historical Society

Originally published on The Conversation as Infrastructure spending has always involved social engineering

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.