In 1919, with Prohibition about to end beer production, the owners of the Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company, turned their attention to candy, building a vast complex on Port Washington Road in Glendale.

From its massive purpose-built factory to the staggering amount of money lost in its eight-year history, everything about Milwaukee′s Eline’s Chocolate and Cocoa Co. was outsized.

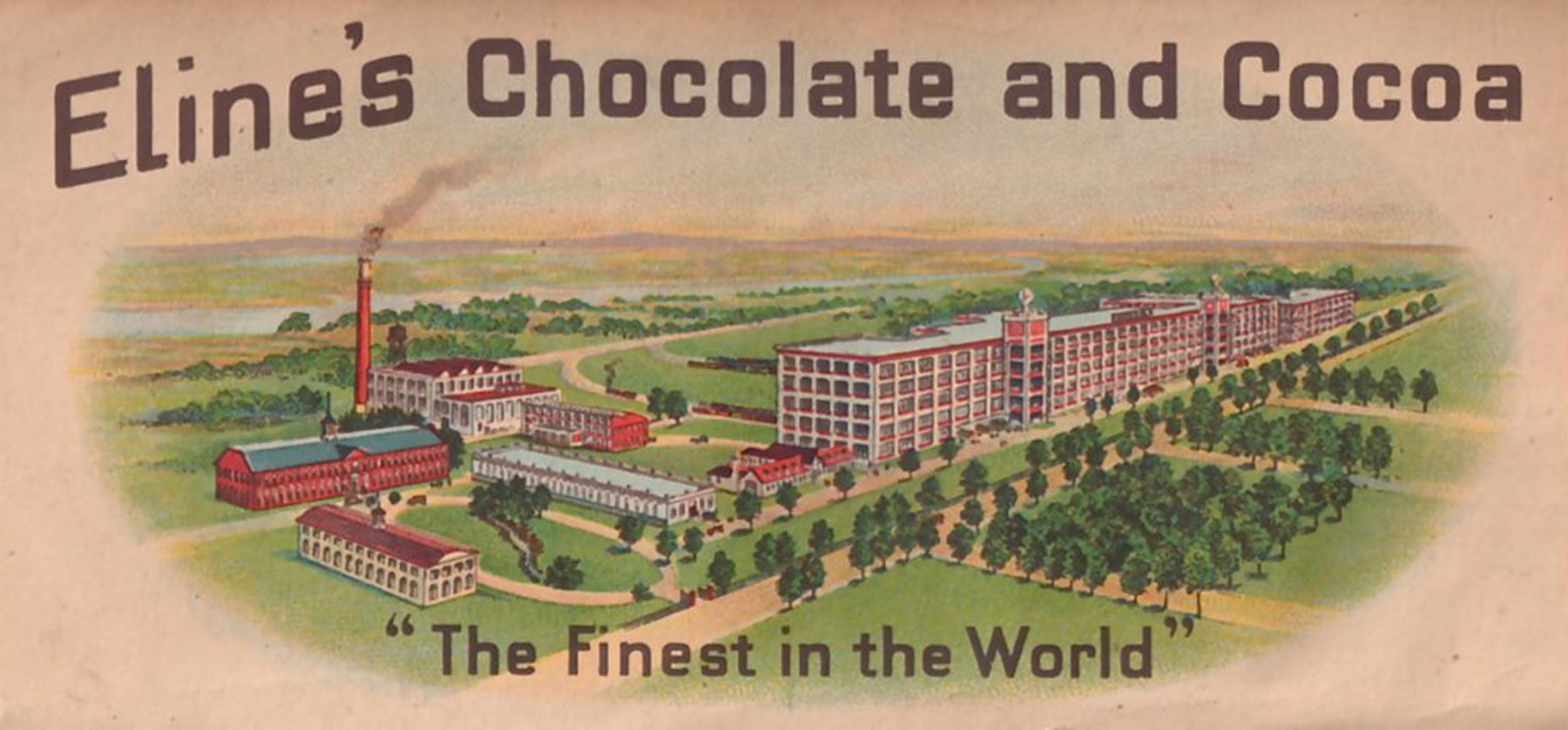

The venture was launched by the Uihlein family, owners of Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company It’s not easy to go from Beer Baron to Count Chocolate but they certainly gave it a good try. The family hired experts, built a sprawling state-of-the-art factory on Port Washington Road in Glendale, hired an army of workers, and launched an ambitious marketing campaign.

Eight years later it was gone. Today only a few buildings remain of the Eline complex, monuments to a mistake.

In 1919, transitioning from beer to bon bons made sense. The 36th state approved the eighteenth amendment at the beginning of that year, making the amendment part of the Constitution and starting the clock ticking.

One year after ratification, on January 17, 1920, it would become illegal to manufacture, sell, or transport alcoholic beverages in the United States.

Consequently, the owners of Schlitz suddenly needed a replacement business as comfortably profitable as brewing had been. The answer, or so it seemed, was right at their doorstep. With 16 established firms employing 2,000 residents, Milwaukee was then a major center of candy production. Most of these companies started very small — Milwaukee’s George Ziegler Candy Co. made its first products on a family’s kitchen stove.

With practically unlimited capital at its disposal and little time before the onset of Prohibition, the Uihlein family decided to enter the market on a huge scale.

“Here is the ideal location,” Joseph E. Uihlein Sr., president of the newly formed Eline’s Chocolate Co., said in 1919. “Wisconsin is the greatest dairy state in the union and good fresh milk is the one requirement for a chocolate manufacturer. We have made plans for unlimited expansion.”

Looking back years later in an interview with the Milwaukee Journal, his son, Joseph Jr., said, “My father had the theory that with beer and liquor cut off, people would turn to chocolate. Instead of starting in a small way, the family built a tremendous plant.”

“Until then, my father had tasted nothing but success all his life,” he added.

That would soon change.

But what a factory he built! Willy Wonka had nothing on Joseph Uihlein. Newspapers wrote of lobbies paved with marble imported from Italy, of fireplaces in every office, and of a garage modeled after the orangery at Apthorpe Hall in England. The entrance pillars were inspired by those at Harvard University.

And then there was the gatehouse.

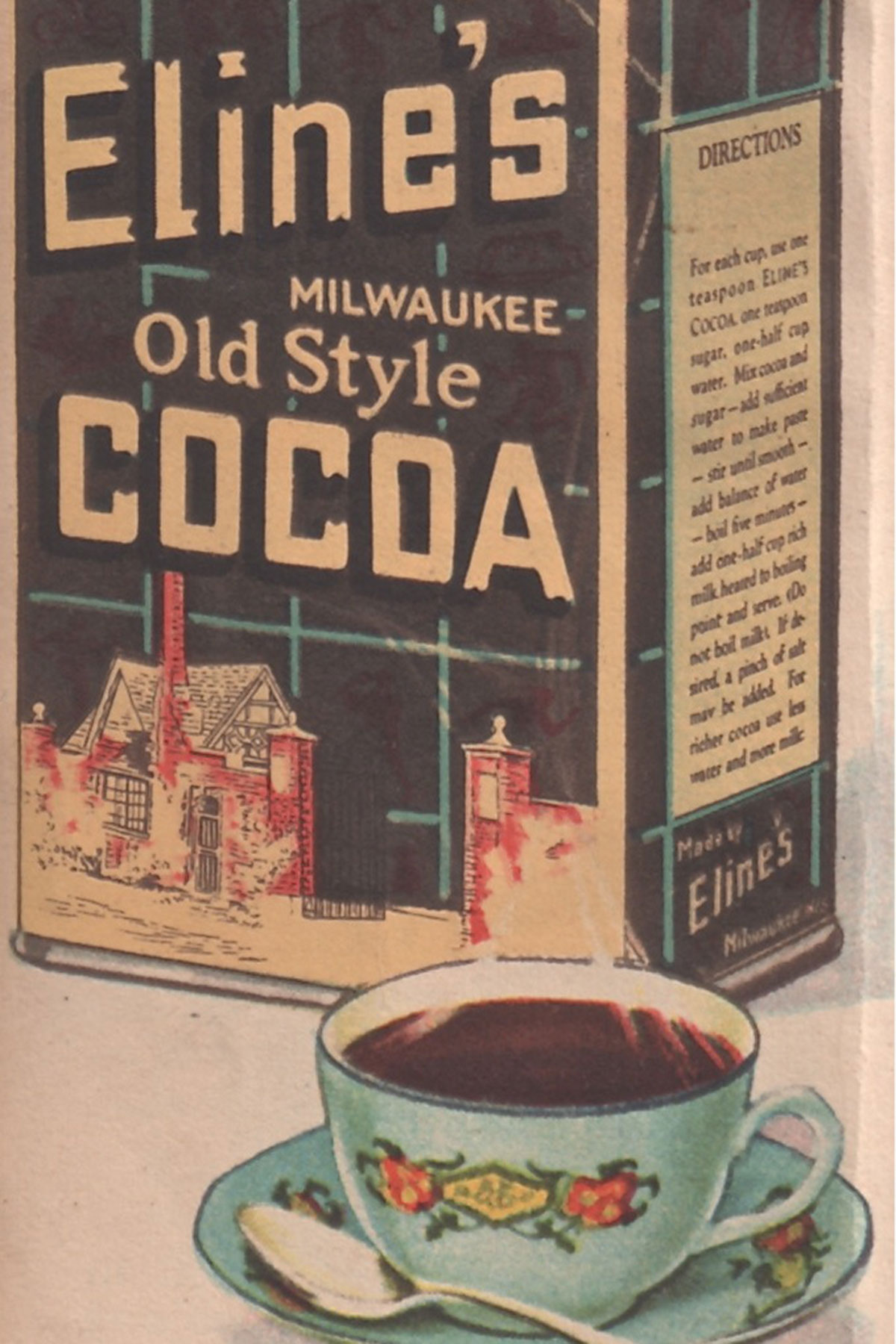

A company publication from the 1920s, titled the Gate to Eline, describes what was essentially a guardhouse as a vision of Old World charm. “If you are afoot you will enter through the sidewalk gate and notice the hand-hewn timbers of the old English Gatehouse, tell the time by the quaint, old sundial, or perhaps be greeted by the doves from their cotes. Or, if you come by motor, the Lodge Keeper will come at your call to spread the hand-wrought iron gates, copies of the celebrated gates at Drayton House, England.”

As early as 1924, there were rumors the Uihleins were looking to sell the business. But just two years later they added 400 salesmen, retooled the factory to the tune of $1 million, and added a line of hard candies. In the end, it was simply more money down the drain. Two years after that, in 1928, the company was liquidated.

Published accounts focused on the company’s missteps. Eline’s Almond Bars might or might not contain almonds, gum balls sometimes shattered when dropped, and the company briefly used a food-grade lubricant made from fish oil on its packaging machinery, only to discover it made the chocolates taste fishy.

These mishaps made for amusing reading but the real problem was not its products, it was the ocean of red ink into which the company was rapidly sinking. The family invested a fortune to muscle its way into a highly competitive business and failed to capture a significant share of the market. The factory lasted less than 10 years and burned through a reported $17 million.

The English gatehouse with its hand-hewn timbers still stands near the intersection of North Port Washington Road and West River Woods Parkway. Now used for storage, the building’s intricate details are worth a close look. The office building, just to the north, also survives.

The four-story factory was a more-utilitarian affair: a 1920s-style brick and reinforced concrete structure with walls of multi-paned windows. It survived the collapse of the candy company and housed an armaments plant in World War II. It was demolished in the 1970s.

Prohibition ended in 1933 and the Uihlein’s returned to brewing. Presumably the family tried very hard to forget about chocolates.