Wisconsin’s latest dispute over landlord-tenant relations has crucial implications for people enduring abusive relationships.

The state’s regulations on rental housing have been transformed over the past decade, with a new law being enacted every legislative session since 2011. These changes reduce local governments’ power to regulate the rental properties, and generally give landlords more leverage over their tenants. Passed by the Republican-led state Legislature and signed by Gov. Scott Walker, these laws have generally been supported by landlord interest groups. The latest round is no different.

On April 16, 2018, Walker signed Act 317, which limits how long some renters in desperate circumstances can stave off an eviction through the court system. It makes several other changes, as detailed in a Legislative Reference Bureau memo. Wisconsinites struggling to pay rent or a utility bill can apply for Emergency Assistance from the state, in a program funded by the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program. After applying, renters can ask a judge to stay eviction proceedings while their application is processed. But the new law limits the length of that stay, stipulating that it can only remain in effect for “10 working days.” Previously, the allowable length of a stay was more open-ended.

As this provision (part of AB 711) worked its way through the Legislature in early 2018, advocates for domestic violence survivors raised an alarm about putting a cap on the grace period for tenants facing eviction. After a survivor gets out of an abusive relationship, they might face financial difficulties, and this cap could add housing instability to what is already a traumatic and dangerous situation. It could also put more pressure on people in abusive relationships to stay, escalating their risk of future violence or getting killed.

In an April 27 interview on Wisconsin Public Television’s “Here & Now,” one of the bill’s proponents, Apartment Association of Southeast Wisconsin president Ron Hegwood rejected the potential financial fallout of domestic abuse.

“Well, I’m not sure why we assume that there’s domestic abuse and an automatic economic problem with that. I mean, that’s more of an emotional issue than an economic issue,” Hegwood said. “If you have a domestic abuse, again, I go — that’s an emotional situation, not an economic situation. So I wouldn’t equate those two things together.”

When reached for additional comment on April 30, Hegwood told WisContext that he regretted that response to the “Here & Now” question about domestic violence. A landlord in the Milwaukee area, Hegwood said he takes domestic violence seriously and knows that financial manipulation can be a component of abuse. However, he supports Act 317 and its provision limiting stays on eviction.

Hegwood said that by the time a landlord starts eviction proceedings against a tenant, they’re often already dealing with a difficult situation.

“You’re already out two or three months rent, you’re trying to work with the person … [Domestic violence] is an important social issue, so society has to decide how to treat this. It’s not fair to put the burden of this on the landlord and say ‘You have to let this person stay indefinitely.'”

The work of helping domestic violence victims overcome crisis falls to many organizations and individuals, though. Victims can seek out public and private resources, including shelters and the federal emergency assistance fund. For groups that support domestic violence victims and researchers who study it, the financial aspects of abuse are a relevant consideration when it comes to housing policy and the relationship between tenants and landlords.

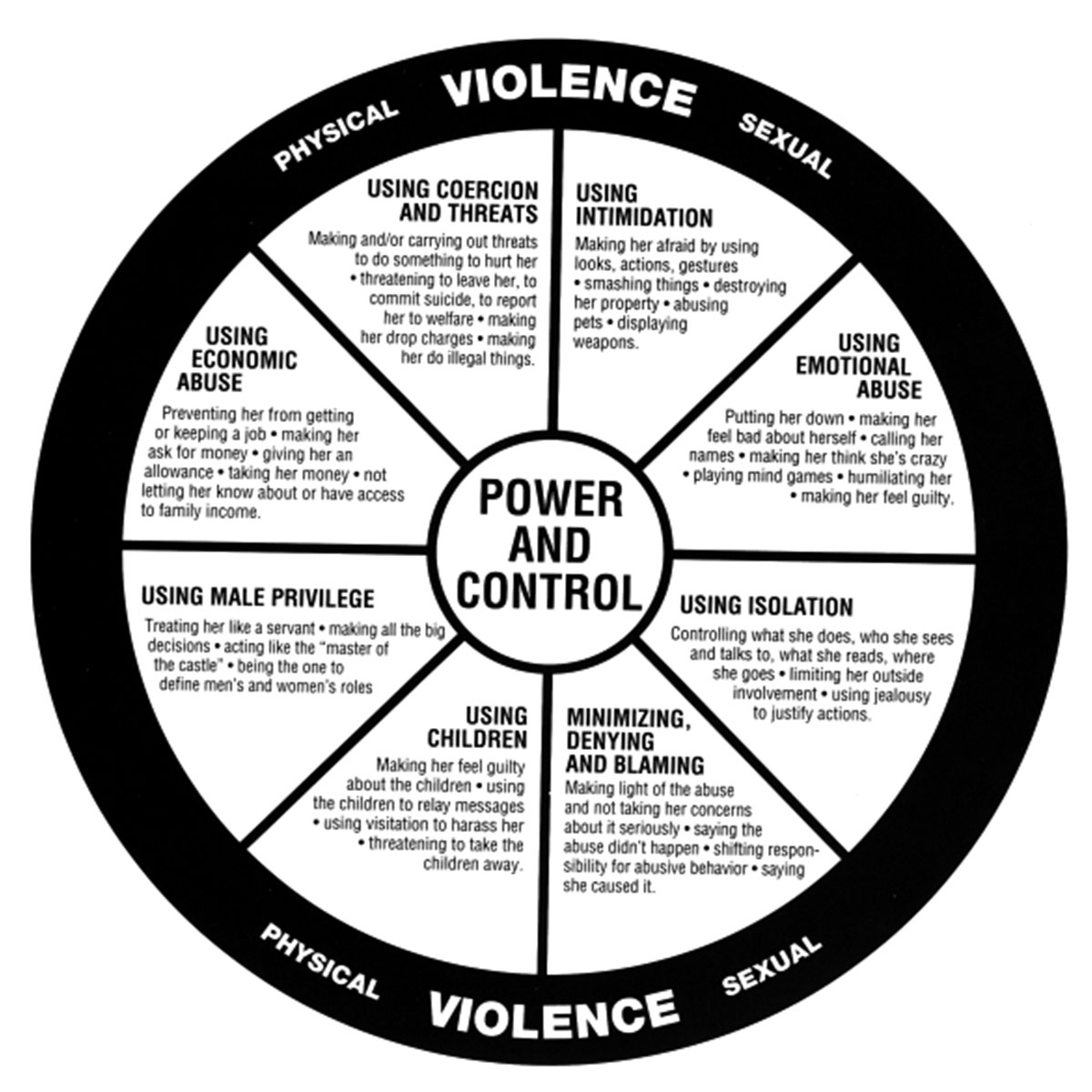

Any distinctions between “emotional” and “economic” don’t exist in the messy reality of abusive relationships. Emotional abuse is about power, and money is one major element of imbalances.

What the research says about financial abuse

A research brief published by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Financial Security in 2011 reported that all but one of 103 domestic violence survivors interviewed in a previous study had experienced financial abuse.

Most commonly, abusers claim control over the household budget, make financial decisions on a unilateral basis, force their victims to ask them for an “allowance,” and/or obsessively track spending by demanding receipts. Other forms of economic abuse include interfering with a victim’s efforts to gain an education or maintain stable employment, freeloading off the victim, or deliberately paying bills late in the victim’s name to damage the victim’s credit score.

“When people think of domestic violence, generally the physical and psychological abuse come to mind,” said Adrienne Adams, a professor of ecological and community psychology at Michigan State University and author of the 2011 UW Center for Financial Security research brief. “Often people don’t realize that abusers also systematically restrict and exploit their partners’ economic resources in order to have control over their lives, and that this behavior has serious consequences for victims’ immediate and future economic well-being and safety.”

One caveat about financial abuse studies is that they tend to focus on survivors who sought help — therefore, researchers have yet to figure out how prevalent it is in the general population.

Adams led a new study, forthcoming in the peer-reviewed journal Violence Against Women, that delves specifically into “coerced debt,” a situation in which an abuser racks up debt in their victim’s name. This practice means the victim will have a lower credit score, making it more difficult for them to gain financial independence. It also creates an array of additional threats within the relationship; victims fear that should they confront their abuser about a suspicious credit card charge, for instance, the perpetrator may inflict further physical or emotional harm.

Adams and her co-authors surveyed 1,863 women who called a nationwide domestic violence hotline in the summer of 2014. Of those women, 52 percent reported experiencing coerced debt.

This type of abuse affects housing. If a victim effectively has no money of their own, it’s difficult to keep up with rent on a new place while also trying to establish a steady income, or to take over a lease. If a victim’s credit has been deliberately damaged, then even applying for an apartment might be much harder.

The coerced-debt study by Adams addresses effects on housing issues directly, noting that bad credit hinders more than just access to conventional loans.

“The reality is that employers, landlords, and utility companies make extensive use of credit reports and scores in screening potential employees, tenants and customers, which can prevent victims from obtaining jobs, housing and basic utilities,” she said.

A fact sheet from Madison-based Domestic Abuse Intervention Services cites “approval for housing rental and paying a security deposit” as the number-one financial barrier victims face to leaving. Additionally, a 2015 study from the Rutgers University School of Social Work noted “women who are forced to become economically dependent on their partner are at greater risk of being further abused and are less likely to leave the relationship.”

That study, led by Judy Postmus, a social work professor and director of the Center on Violence Against Women and Children at Rutgers, also discussed how previous research might have failed to capture the scope of money’s role in domestic abuse. Some earlier studies, it noted, tended to ask a single question about whether or not the victim had experienced economic abuse. The Rutgers study instead asked about 28 specific behaviors that fall under the rubric of financial abuse.

The courts and a dangerous transition time

Limiting the ability of courts to stay an eviction makes it harder to protect domestic violence victims at a time when they’re “incredibly vulnerable,” said Chase Tarrier, public policy coordinator for End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin, a statewide umbrella organization for domestic-abuse victim advocacy and services. Victims run the highest risk of being killed when they are taking steps to leave an abusive situation, Tarrier said.

It is possible, he added, that someone in those circumstances could scrape together a security deposit and the first month’s rent on a new apartment, but then struggle to find steady work and keep up with rent and bills. That’s when someone might seek out emergency assistance funds — and need a grace period to get those funds and get caught up on rent.

The application process for emergency assistance support is supposed to take five days, Tarrier said, “but what we often hear is that it takes much much longer than that, sometimes months, to either get or be denied.”

The authors of Act 317 initially limited eviction stays to five days, but changed it to 10 days in response to domestic violence advocates’ concerns. Tarrier said that period is still inadequate. He also rejected the notion that the previous wording of Wisconsin’s eviction law put too much burden on landlords.

“We’re not asking for landlords to be forced to do anything for anybody in any situation,” Tarrier said. “We’re talking about a very specific group of people who are experiencing a very specific set of circumstances, the people who are eligible for emergency assistance have to be parents and they’re [Temporary Assistance for Needy Families]-eligible, which means they are at a certain level of poverty.”

In a separate April 27 interview on “Here & Now,” Aaron Romens of Madison renters’ advocacy organization Tenant Resource Center, did not directly address domestic abuse. But he explained that the group opposed Act 317 and other changes to Wisconsin’s landlord-tenant laws due to the pressures they place on renters.

“Landlords, especially property managers — it’s their job to understand all of these different law changes. Meanwhile tenants, they already have other jobs,” Romens said. “I believe that all these changes just continue to create confusion to the point where tenants now almost need to take out a second-time job just to catch up with all these changes.”

Scott Gordon

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension, and originally published as How Domestic Violence Intertwines With Landlord-Tenant Relationships