A nurse wounded by a Russian sniper was spirited out wrapped in sheets. Another, sickened by the thought of working for the people who destroyed his home, sneaked out a side door and walked out through Mariupol’s shattered streets.

Doctors shed their scrubs for street clothes. And one by one, the staff of the largest hospital in the Donetsk region of eastern Ukraine slipped away as Russian forces seized control of the city’s center.

Months later, around 30 staff members from Mariupol’s Hospital No. 2 have reassembled in Kyiv. Along with 30 specialists from a cardiac hospital in Kramatorsk, a Donetsk city that remains under Ukraine’s control, they are opening a pared-down version of a public hospital to help displaced Ukrainians in need of care.

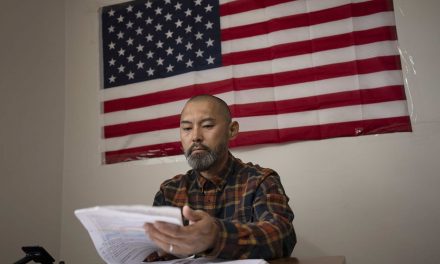

Dmytro Gavro, a nurse who is studying to become a cardiologist, recalls each child who arrived at the hospital in Mariupol during the dark days of March, when the city was under siege and bombardment following Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine.

“I remember everyone, starting from the first girl who was brought to us and ending with the two last children, who were brought to us shortly before the occupation of our hospital,” Gavro said. He said he fled Mariupol because he could not work for the Russians, who focused on the port city as a strategic prize and bombed into surrender over 86 days.

“I could not obey those who destroyed my life,” he said. “I don’t have a single photo, not a single childhood memory. I don’t have a single photo with my family. I don’t have any photos of my parents from my childhood. Everything burned down at home.”

Accompanied by the only people who understand what he’s been through, Gavro, 21, sees the new hospital in Ukraine’s capital as a sort of rebirth,

“It is precisely our hospital that is proof of this, that everything is possible. Everything is possible, you can start from scratch and do this,” he said the day before the hospital welcomed a handful of patients.

Much of Ukraine’s medical infrastructure is going to have to be rebuilt from scratch. The World Health Organization has documented 715 attacks on health care in Ukraine during the war.

A recent study released by the Ukrainian Health Care Center found nearly 80% of the medical facilities in Mariupol alone were damaged or destroyed, or 82 out of the 106 locations the center analyzed with a combination of satellite imagery and witness testimony.

“Almost the entire critical medical infrastructure of the city is among the destroyed medical facilities,” the report said.

Maryna Gorbach’s last memory of Hospital No. 2 was not as a nurse but as a patient. A Russian sniper’s bullet struck her in the jaw on March 11 as Russian tanks and troops surrounded the building.

By then, the hospital was treating almost exclusively civilian victims of the war, but its hallways were filled with Mariupol residents who had nowhere else to go.

Gorbach’s two teenage daughters were in the basement of their home across the city, with no idea what had happened to their mother. Two Associated Press journalists at the hospital that day witnessed the shooting, as well as the approach of Russian forces that night.

By the time Russian soldiers seized control of the entire hospital on March 13, Gorbach was half-delirious in intensive care.

“They counted the patients, counted the employees, so that no one would leave. They said they would shoot any doctors who left,” recalled Gorbach, a neurology nurse. So quietly, colleagues wrapped her in sheets and drove her away in a car. It was March 16.

She never wanted to work in medicine again.

But when Gorbach finally made her way to Kyiv, she found the same colleagues who had worked by her side for so long and then saved her life – and she realized that something had healed.

“The desire to live reappeared,” she said. “We had all endured it all together. Therefore, here we understand each other so much from a half-word, from a half-look. You know, Mariupol residents now understand each other just like that with words, eyes, gestures, tears.”