On the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington this summer, a few Black queer advocates spoke passionately before the main program about the ongoing struggle for LGBTQ+ rights. As some of them got up to speak, the crowd was still noticeably small.

Hope Giselle, a speaker who is Black and trans, said she felt the event’s programming echoed the historical marginalization and erasure of Black queer activists in the Civil Rights Movement. However, she was buoyed by the fact that prominent speakers drew attention to recent efforts to turn back the clock on LGBTQ+ rights, like the attacks on gender-affirming care for minors.

And despite valid concerns around the visibility of Black queer advocates in activist movements, progress is being made in elected office. In early October, Senator Laphonza Butler made history as the first Black and openly lesbian senator in Congress, when California Governor Gavin Newsom appointed her to fill the seat held by the late Dianne Feinstein.

Rectifying the erasure of Black queer civil rights giants requires a full-throated acknowledgment of their legacies, and an increase of Black LGBTQ+ representation in advocacy and politics, several activists and lawmakers told The Associated Press.

“One of the things that I need for people to understand is that the Black queer community is still Black,” and face anti-Black racism as well as homophobia and transphobia, said Giselle, communications director for the GSA Network, a nonprofit that helps students form gay-straight alliance clubs in schools.

“On top of being Black and queer, we have to also then distinguish what it means to be queer in a world that thinks that queerness is adjacent to Whiteness — and that queerness saves you from racism. It does not,” she said.

Butler said she hopes that her appointment points toward progress in the larger cause of representation.

“It’s too early to tell. But what I know is that history will be recorded in our National Archives, the representation that I bring to the United States Senate,” she said last week. “I am not shy or bashful about who I am and who my family is. So, my hope is that I have lived out loud enough to overcome the tactics of today.”

“But we don’t know yet what the tactics of erasure are for tomorrow,” Butler said.

Butler is a bellwether of increased visibility of queer communities in politics in recent years. In fact Black LGBTQ+ political representation has grown by 186% since 2019, according to a 2023 report by the LGBTQ+ Victory Institute. That included the election of now-former New York Representatives Mondaire Jones and Ritchie Torres, who were the first openly gay Black and Afro-Latino congressmen after the 2020 election, as well as former Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot.

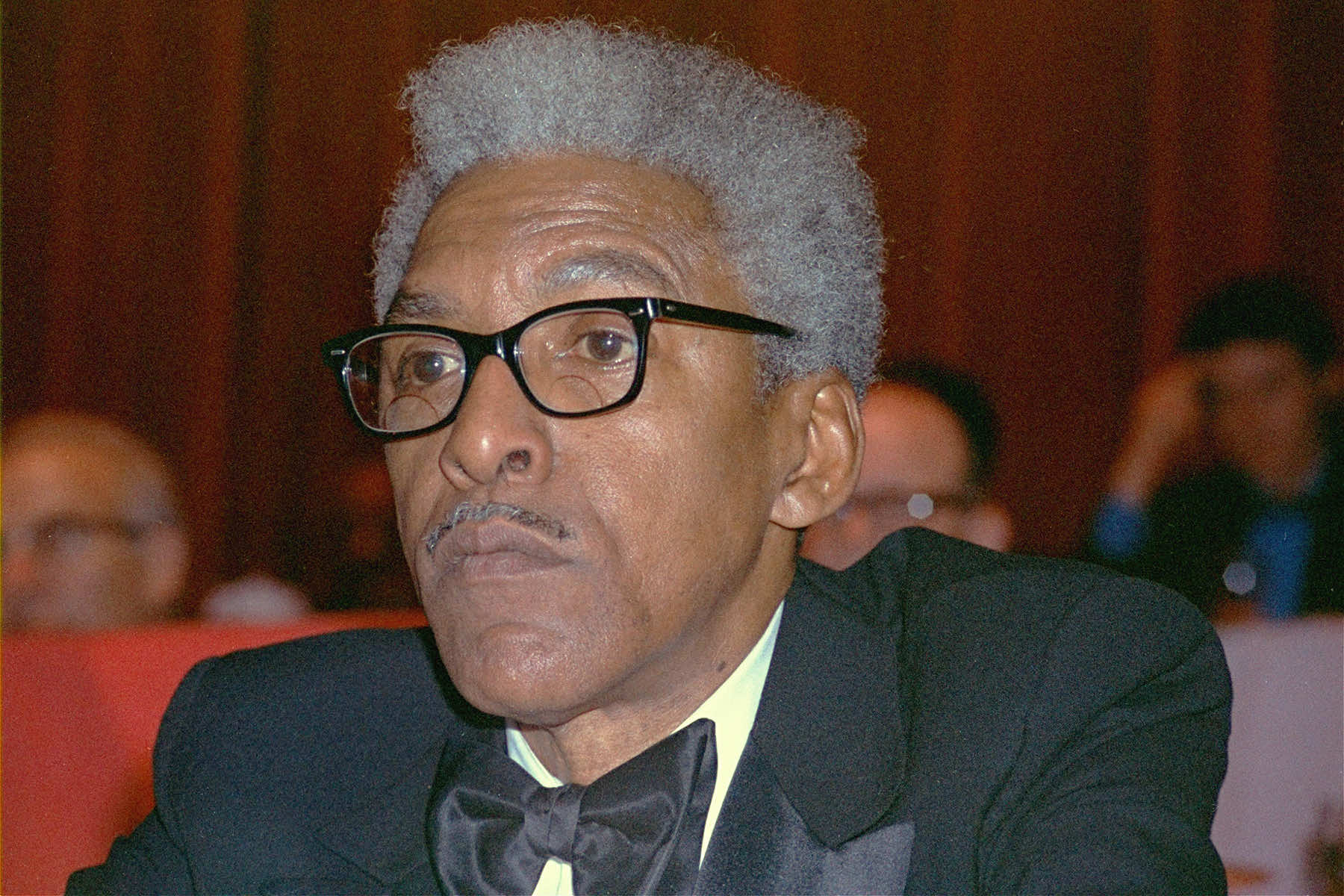

These leaders stand on the shoulders of civil rights heroes such as Bayard Rustin, Pauli Murray, and Audre Lorde. In accounts of their contributions to the Civil Rights and feminist movements, their Blackness is typically amplified while their queer identities are often minimized or even erased, said David Johns, executive director of the National Black Justice Coalition, a LGBTQ+ civil rights group.

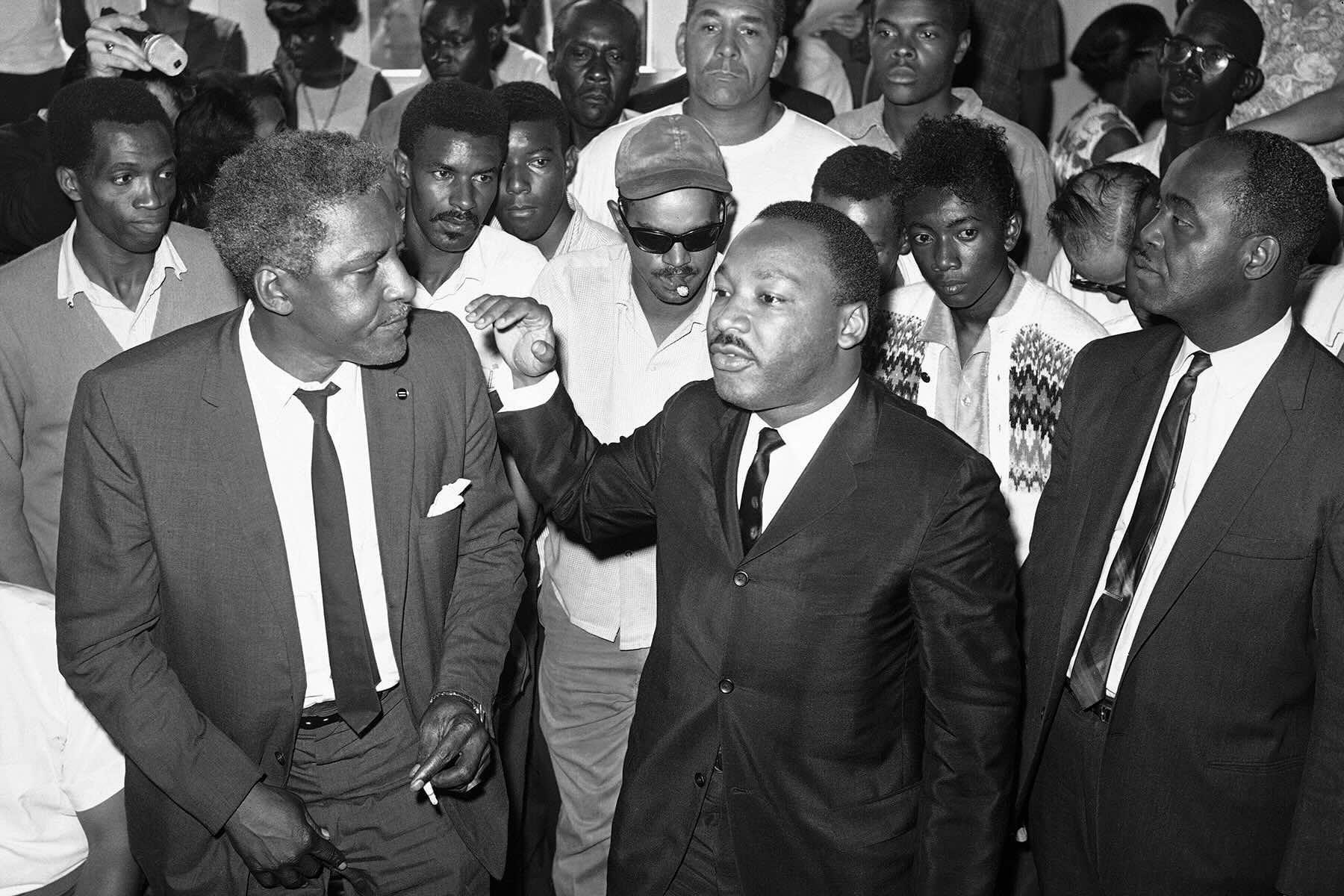

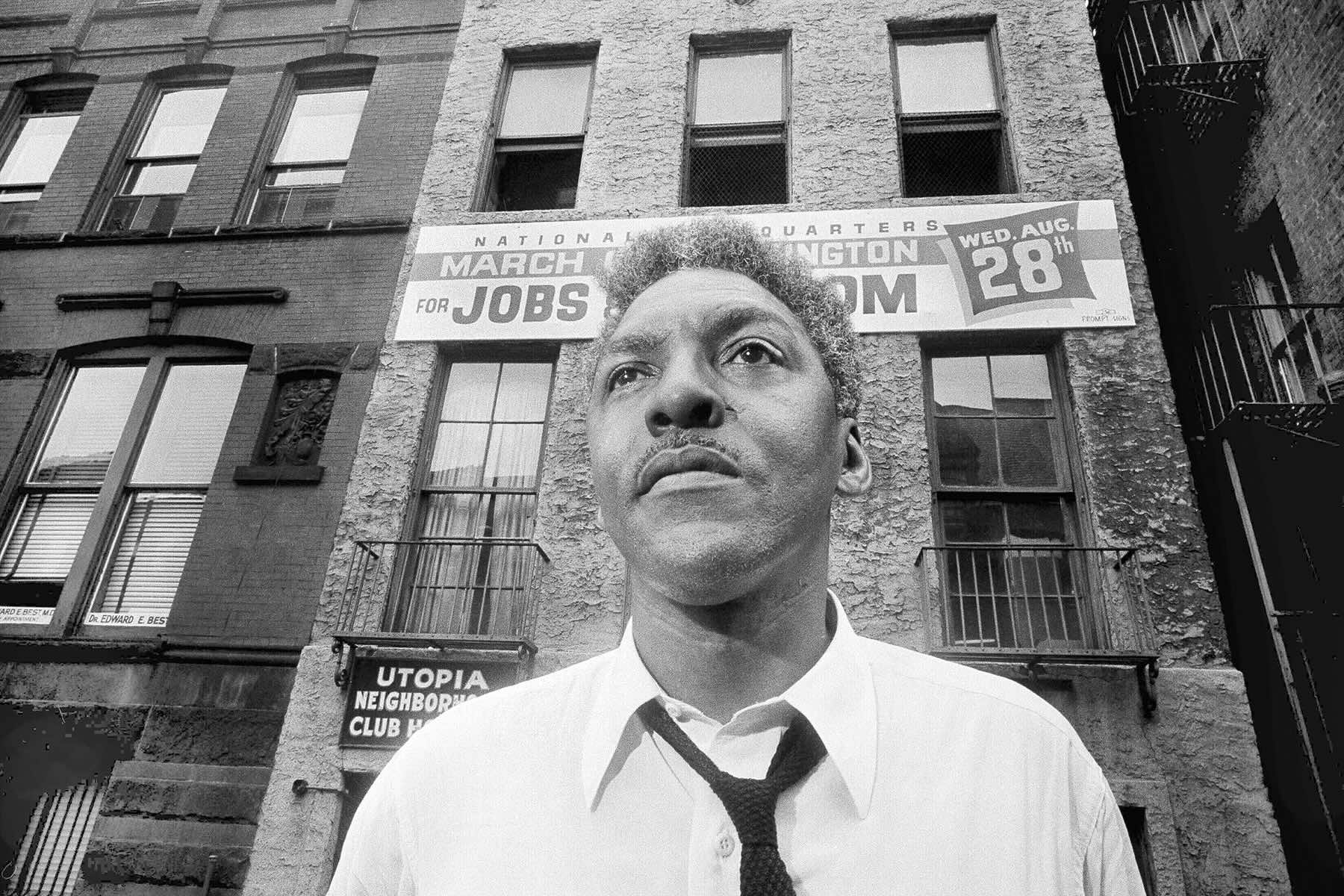

Rustin, who was an adviser to the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and a pivotal architect of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, is a glaring example. The march he helped lead tilled the ground for the passage of federal civil rights and voting rights legislation in the next few years.

But the fact that he was gay is often reduced to a footnote rather than treated as a key part of his involvement, Johns said.

“We need to teach our public school students history, herstory, our beautifully diverse ways of being, without censorship,” he said.

An upcoming biopic of Rustin’s life will undoubtedly help thrust the topic of Black LGBTQ+ political representation into the public conversation, said Shay Franco-Clausen, a commissioner of Alameda County in California.

“I didn’t even learn about those same leaders, Black leaders, Black queer leaders until I got to college,” she said.

The film, titled “Rustin,” debuted in select theaters on November 3, then Netflix on November 17.

Some believe the erasure of Black LGBTQ+ leaders stems from respectability politics, a strategy in some marginalized communities of ostracizing or punishing members who don’t assimilate into the dominant culture.

White Supremacist ideology in Christianity, which has been used more broadly to justify racism and systemic oppression, has also promoted the erasure of Black queer history. The Black Christian church was integral to the success of the Civil Rights Movement, but it is also “theologically hostile” to LGBTQ+ communities, said Don Abram, executive director of Pride in the Pews.

“I think it’s the co-optation of religious practices by White Supremacists to actually subjugate Black, queer, and trans folk,” Abram said. “They are largely using moralistic language, theological language, religious language to justify them oppressing queer and trans folk.”

Not all queer advocacy communities have been welcoming to Black LGBTQ+ voices. Minneapolis City Council President Andrea Jenkins said she is just as intentional in amplifying queer visibility in Black spaces as she is amplifying Blackness in majority White, queer spaces.

“We need to have more Black, queer, transgender, nonconforming identified people in these political spaces to aid and bridge those gaps,” Jenkins said. “It’s important to be able to create the kinds of awareness on both sides of the issue that can bring people together and that can ensure that we do have full participation from our community.”

Black LGBTQ+ leaders are also using their platforms to create awareness about groundbreaking historical figures, especially Rustin. Maryland Delegate Gabriel Acevero and several LGBTQ+ advocates fought to get the only elementary school in his district named after Rustin in 2018. He has also urged Congress to pass legislation to create a U.S. Postal Service stamp depicting Rustin.

“Black queer folks have contributed to so many movements that we do not get acknowledgment for,” Acevero said. “And this is why we should not only ensure that our elders get their flowers, but we should push to have their names and statues built … so that they are not forgotten.”