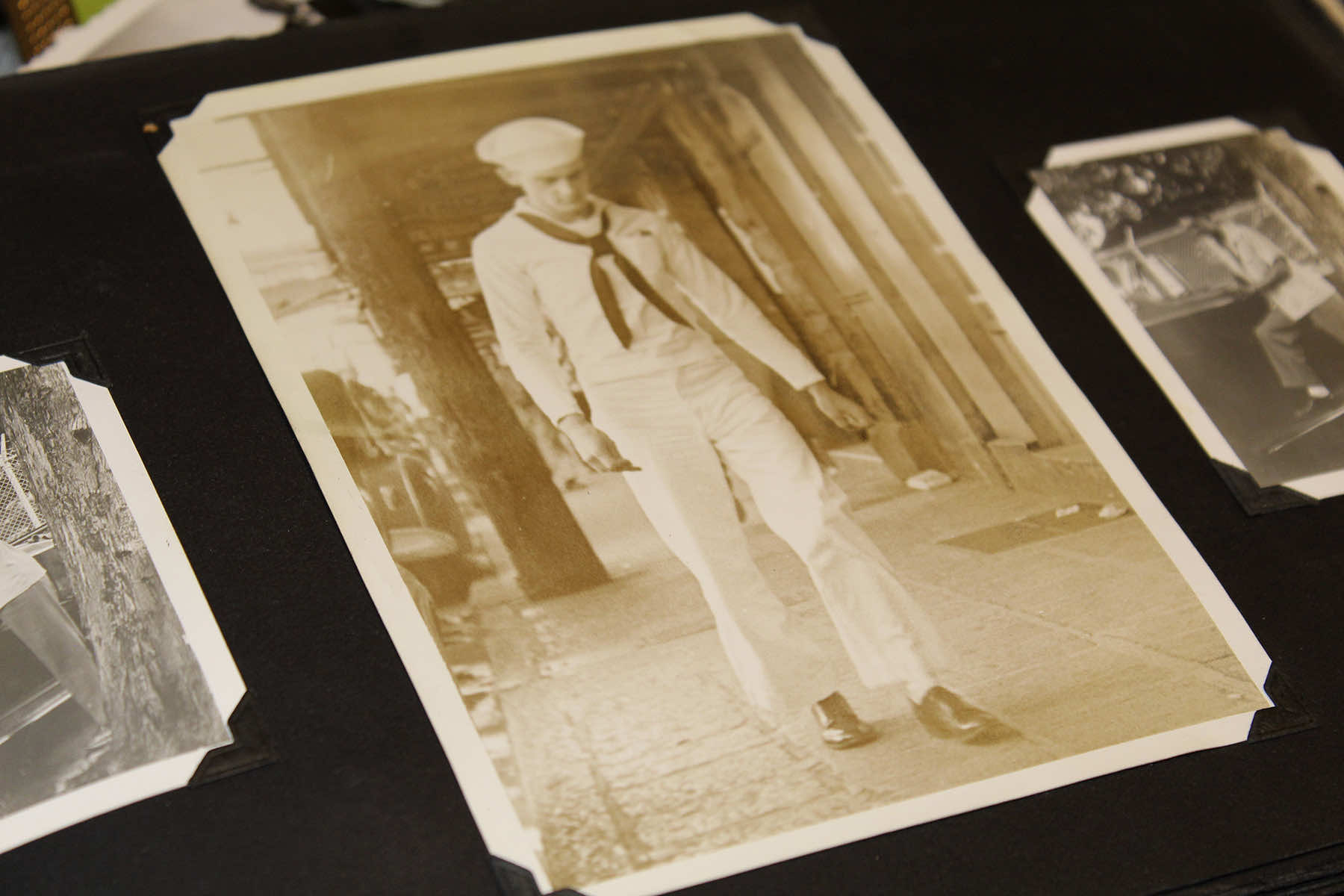

Ira “Ike” Schab had just showered, put on a clean sailor’s uniform and closed his locker aboard the USS Dobbin when he heard a call for a fire rescue party.

He went topside to see the USS Utah capsizing and Japanese planes in the air. He scurried back below deck to grab boxes of ammunition and joined a daisy chain of sailors feeding shells to an anti-aircraft gun up above. He remembers being only 140 pounds (63.50 kilograms) as a 21-year-old, but somehow finding the strength to lift boxes weighing almost twice that.

“We were pretty startled. Startled and scared to death,” Schab, now 103, said at his home in Beaverton, Oregon, where he lives with his daughter. “We didn’t know what to expect and we knew that if anything happened to us, that would be it.”

Eighty-two years later, Schab returned to Pearl Harbor on December 7 on the anniversary of the attack to remember the more than 2,300 servicemen killed. He was one of five survivors at a ceremony commemorating the assault that propelled the United States into World War II. Six of the increasingly frail men had been expected, but one was not feeling well, organizers said.

The aging pool of Pearl Harbor survivors has been rapidly shrinking. There is now just one crew member of the USS Arizona still living, 102-year-old Lou Conter of California. Two years ago, survivors who attended the 80th anniversary remembrance ceremony ranged in age from 97 to 103. They will be even older this time.

David Kilton, the National Park Service’s interpretation, education and visitor services lead for Pearl Harbor, noted that for many years survivors frequently volunteered to share their experiences with visitors to the historic site. That’s not possible anymore.

“We could be the best storytellers in the world and we can’t really hold a candle to those that lived it sharing their stories firsthand,” Kilton said. “But now that we are losing that generation and won’t have them very much longer, the opportunity shifts to reflect even more so on the sacrifices that were made, the stories that they did share.”

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs does not keep statistics for how many Pearl Harbor survivors are still living. But department data show that of the 16 million who served in World War II, only about 120,000 were alive as of October and an estimated 131 die each day.

There were about 87,000 military personnel on Oahu at the time of the attack, according to a rough estimate compiled by military historian J. Michael Wenger.

Schab never spoke much about Pearl Harbor until about a decade ago. He’s since been sharing his story with his family, student groups and history buffs. And he’s returned to Pearl Harbor several times since.

The reason … “To pay honor to the guys that didn’t make it,” he said.

December 7’s ceremony was held on a field across the harbor from the USS Arizona Memorial, a white structure that sits above the rusting hull of the battleship, which exploded in a fireball and sank shortly after being hit. More than 1,100 sailors and Marines from the Arizona were killed and more than 900 are entombed inside.

A moment of silence began at 7:55 a.m., the same time the attack began on December 7, 1941.

Harry Chandler, 102, who was a Navy Hospital Corpsman 3rd Class, raised the flag at a mobile hospital in Aiea Heights in the hills above Pearl Harbor in 1941. Gazing over the water from his front row seat on the ceremony grounds on December 7, Chandler said the memories of the USS Arizona blowing up still come back to him today.

“I saw these planes come, and I thought they were planes coming in from the states until I saw the bombs dropping,” Chandler said. They took cover and then rode trucks down to Pearl Harbor where they attended to the injured.

He remembers sailors trapped on the capsized USS Oklahoma tapping on the hull of their ship to get rescued, and caring for those who eventually got out after teams cut holes in the ship.

“I look out there and I can still see what’s going on. I can still see what was happening,” said Chandler, who today lives in Tequesta, Florida.

The Dobbin lost three sailors, according to Navy records. One was killed in action and two died later of wounds suffered when fragments from a bomb struck the ship’s stern. All had been manning an anti-aircraft gun.

That Sunday morning had started peacefully for Schab. He was expecting a visit from his brother, who was also in the Navy and was assigned to a naval radio station in Wahiawa, north of Pearl Harbor. The two never did get together that day.

Schab spent most of World War II in the Pacific with the Navy, going to the New Hebrides, now known as Vanuatu, and then the Mariana Islands and Okinawa.

He was never wounded. He told the Best Defense Foundation in an online interview three years ago that he must have had a guardian angel.

“You’re scared stiff, but you stagger through the events as they happen and hope everything’s going to turn out all right,” he said.

After the war, he worked on the Apollo program sending astronauts to the moon as an electrical engineer at General Dynamics. In retirement he volunteered as a state park docent in Malibu, California, explaining the migration patterns of monarch butterflies.

A tuba player in the Navy, Schab stayed close with his bandmates long after the war. For decades, they organized annual reunions, said his daughter Kimberlee Heinrichs.

Schab has slowed down in recent years. But he still gets together each week for cocktails over Zoom with younger members of his fraternity, Delta Sigma Phi. He drinks cranberry-raspberry juice.

These days, he is happiest listening to big band jazz and audiobooks and going out to meet new people, Heinrichs said.

At his age, he’s thankful to still be able to return to Pearl Harbor. Heinrichs is going with him, along with caregivers. The family has a GoFundMe account to help them raise money for the pilgrimage.

“Just grateful that I’m still here,” Schab said. “That’s really how it feels. Grateful.”