“The ‘trickle-down’ Theory: The principle that the poor, who must subsist on table scraps dropped by the rich, can best be served by giving the rich bigger meals.” – William Blum

It was reported that as soon as a Democrat is back in the White House, Republicans intend to retrench and be careful about how the country spends money, although during Trump’s term, even before the pandemic, they spent huge sums without worrying about it.

This is a pattern. Since President Ronald Reagan’s presidency in the 1980s, Republicans have insisted that tax cuts will pay for themselves by stimulating economic growth, thus increasing tax revenues as everyone gets richer. At the same time, they have dramatically increased military spending without ever suggesting a way to pay for it. Then they complain about the debt, and insist that the only way to get our finances back into whack is to cut domestic spending.

There are two important metrics involved in figuring out our national expenses. One is the deficit, which is the difference between the money the government spends every year and the money it takes in. The other is the debt, which is the total amount the government owes.

Until the late twentieth century, the government took on large debt during the Civil War, WWI, WWII and during the Great Depression, when Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt initiated a new kind of government that regulated business, provided a basic social safety net, and promoted infrastructure. But leaders of both parties believed that deficits should reflect emergencies and that debt should be held at a low percentage of the nation’s Gross Domestic Product, used to estimate the growth of the economy. It was to pay down the national debt that the Republican Party created national taxation, including the income tax, during the Civil War, and that Republican Dwight Eisenhower kept the top income tax bracket at 91% during his administration. Eisenhower was the last Republican president to balance a budget.

After the Great Depression, taxes and the social welfare programs they funded created what economists call the “great compression” when economic inequality in America shrank.

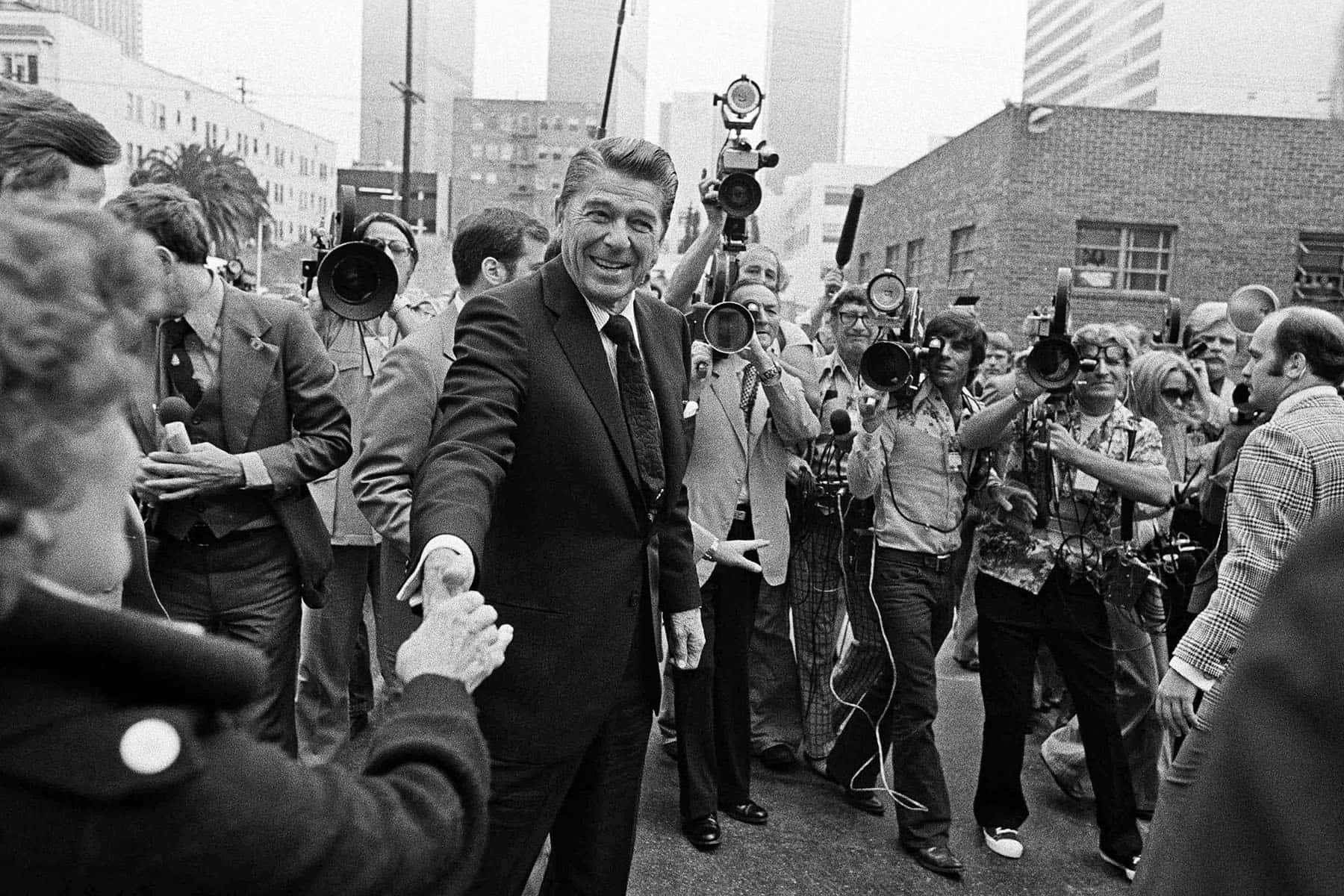

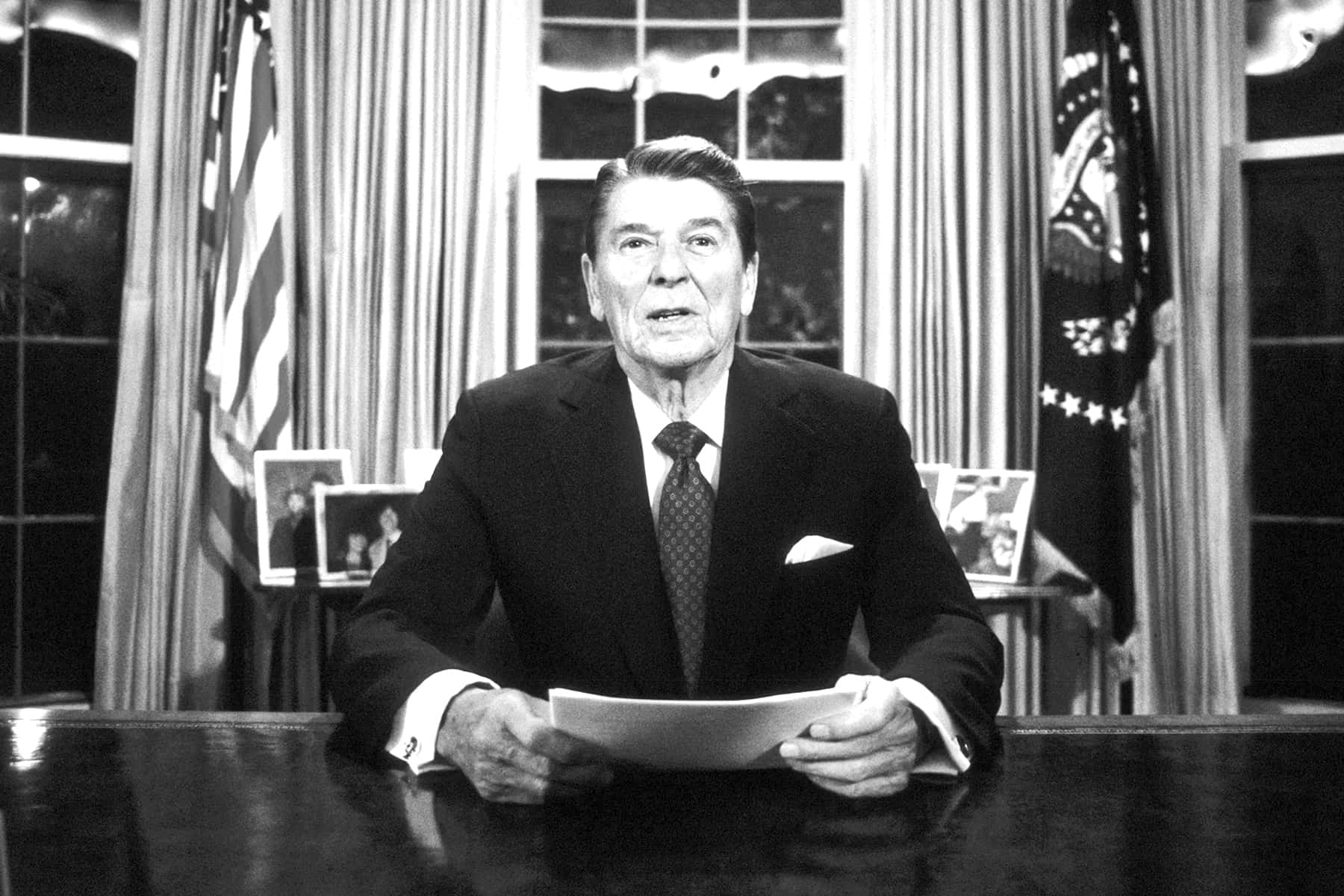

But the stagflation of the 1970s drove white families into higher tax brackets without giving them more buying power at the same time that politicians eager to end business regulation and social welfare programs told them that their tax dollars were going to the civil rights protesters that featured so prominently on the evening news. In 1980, they voted for a president who promised to cut the taxes that he insisted were going to “welfare queens” and to put money back in their pockets.

Ronald Reagan promised that cutting taxes would actually produce more revenue. As business leaders—the supply side—had more money, they would invest in businesses which would hire more workers, at better wages. Rather than focusing on the demand side of the equation—the workers—as governments had done since FDR fought the Depression with the New Deal, Reagan said he could jump-start the economy by putting money into the supply side. The man who would become his own vice president, George H.W. Bush, called this idea “voodoo economics,” but who would complain about a plan that enabled Americans to have the government programs they had come to depend on, without having to pay for them?

Unfortunately, it actually was voodoo economics. In 1981, Congress cut $35 billion from the next year’s budget and cut the top income tax rates from 70% to 50%, as well as cutting capital gains and estate taxes. At Reagan’s urging, it also added $17 billion in new defense spending. In the next five years, it would increase defense spending by 40%. As that money (and more, from the deregulation of savings and loan banks, and from lower interest rates) boosted the economy, it seemed that supply-side economics worked.

An up-and-coming Republican spokesman named Grover Norquist insisted that voters did not want to be taxed to pay down deficits, and it was clear they didn’t have to be. When Democrats called for higher taxes and defense cuts to balance the deficit, Republicans accused them of being anti-business and soft on communism.

But the booming economy was paid for by extensive borrowing. During Reagan’s years in office, the federal debt tripled from $994 billion to $2.8 trillion, and America went from being a creditor nation to a debtor nation. Republican leaders insisted that the Democrats were responsible for the rising debt because they would not make sufficient cuts in domestic spending, but in fact increased defense spending meant the administration itself never submitted a balanced budget.

When he took office, George H.W. Bush tried to take on the national debt, which was costing Americans $200 billion a year in interest payments. In 1990, facing a $171 billion deficit for the next year, Bush agreed to raise taxes if Democrats agreed to steep spending cuts. Republicans led by Georgia Representative Newt Gingrich signed onto the deal in private, but in public began to force those willing to raise taxes, people they called RINOs—Republicans In Name Only—out of their party. The belief that economic growth depended on cutting taxes had become the test of Republican purity.

In 1993, to deal with budget deficits, President Bill Clinton convinced Congress to raise tax rates on incomes over $250,000—affecting about 1% of Americans—to 39.6%, increase the highest corporate tax rate by 1%, and increase the gas tax. Not a single Republican voted for the measure, but under it, the economy boomed and the annual deficits began to shrink. In 1997, Clinton expanded domestic programs and cut the capital gains tax rate, but even still, in 1998, the government was producing a budget surplus.

Even before he took office, President George W. Bush prepared a $1.6 trillion tax cut to wipe that surplus out. Norquist explained to a reporter that so long as there was money to spend, it would go to social welfare legislation, and the Republicans were determined to starve the government, not feed it. Bush did not get the full cut he wanted, but in June 2001 Congress passed a bill cutting $1.3 trillion over ten years.

Immediately after 9-11, Congress appropriated $358 billion for security before Bush dramatically increased military spending—by $48 billion—while slashing domestic spending. When the administration launched more tax cuts the following year, Bush’s Treasury Secretary, Paul O’Neill, worried about a fiscal crisis. Vice President Dick Cheney disagreed: “Reagan proved that deficits don’t matter.” Bush took the country into war in Afghanistan and Iraq but, for the first time in U.S. history, did not raise taxes to pay for the military actions. Instead, Congress cut taxes again. By 2009, the Congressional Research Service estimated the cost of those wars at $1 trillion.

President Barack Obama took office in early 2009 with the Great Recession in full swing. Deficit spending to restart the economy put the deficit at more than $1.4 trillion that year. As the economy recovered, deficits dropped to $585 billion.

Under Trump, though, they rose dramatically again despite the fact he inherited a growing economy. In 2017, he pushed through a tax cut which increased the 2019 deficit to $984 billion. It was projected to be $1.02 trillion in 2020—a 74% increase in four years of a strong economy—when the coronavirus hit. This meant that interest payments on the federal debt—before coronavirus—were estimated to cost $382 billion, 8.2% of total government spending.

The pandemic, of course, required a huge relief package. The CARES bill appropriated $2.2 trillion, making this year’s deficit projected to be at least $3.7 trillion. Measured against GDP, our accumulated debt is now higher than at any time except in 1946, during World War II. In June 2020, it was $20.3 trillion.

Economists are of two minds (at least!) about the economic effects of deficits and the federal debt, but there is one very clear political meaning to them. This pattern of government spending and taxation since 1981 has moved wealth upward dramatically. In 1979, the top 1% of Americans held 20.5% of the nation’s wealth. In 1989 the top 1% held 35.7%. By 2017, the top 1% owned 40% of the country’s wealth, more than the bottom 90% combined. The top 20% in 2017 owned 90% of the wealth, leaving just 10% for the remaining 80%. The bottom 20% of Americans have no wealth; they are in debt.

When Republicans today say they are going to turn their attention back to the deficits and the debt, what they are saying is that they intend to continue to cut taxes. Then they will blame the Democrats for being fiscally irresponsible when they call for the infrastructure and social welfare spending that used to keep the American economic playing field somewhat level.

Gеоrgе Rоsе and Dіаnа Walkеr

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics