Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson asked whether opponents of Texas’s S.B. 8, the so-called Heartbeat Bill, could bring a Federal case to block the law, which gets around normal challenges by putting private individuals, rather than the state itself, in charge of enforcing it.

By a vote of 5 to 4, the court said they could sue, but it limited that ability so severely that the law itself will remain largely intact. The state law, which went into effect on September 1, prohibits abortion after six weeks of a pregnancy, before most women know they are pregnant.

And yet, the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision of the Supreme Court affirmed that women have the constitutional right to abortion without undue restrictions, primarily in the first trimester of a pregnancy.

This case is about far more than abortion. It is about the Federal protection of Civil Rights in the face of discriminatory state laws. That Federal protection has been the key factor in advancing equal rights in America since the 1950s.

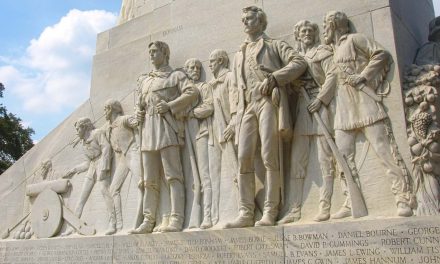

When the Framers wrote the Constitution in 1787, shortly after the American Revolution against a king colonists had come to believe was a tyrant, many leading Americans were still worried about concentrating too much power in the hands of a chief executive and a central government. In order to convince people to ratify the Constitution, leaders called for explicit limits to what the new national government could do to citizens.

In 1791 the nation added ten amendments to the Constitution to protect individual freedom and rights, including, for example, freedom of religion, freedom of the press, protection from unreasonable searches and seizures, the right to a speedy trial, and so on. These limits applied to the Federal government alone.

States could still enact fiercely repressive laws, including, before the Civil War, laws throwing Indigenous Americans off their lands, denying rights to women (including access to their children in the rare instance of divorce), and enslaving Black Americans. In the wake of the war, legislatures in former Confederate states tried to reassert white control through “Black Codes” that severely limited the rights and protections for formerly enslaved people.

Congressmen recognized the need to use the power of the Federal government to override state laws in order to protect equality. In 1866, it passed and sent off to the states for ratification another amendment to the Constitution: the Fourteenth.

The Fourteenth Amendment states that “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The amendment gave Congress the power to enforce the amendment “by appropriate legislation.”

Congress intended for the Fourteenth to enable the Federal government to guarantee that Black Americans had the same rights as white Americans, even in states whose legislatures wanted to keep them in a form of quasi-slavery. The states ratified it and it became part of the Constitution in 1868.

In 1870, as white supremacists organized as the Ku Klux Klan terrorized their Black neighbors, Congress passed a law establishing the Department of Justice, which promptly set out to prosecute Klan members, eventually driving the organization underground.

But Federal protection of Civil Rights was both limited and short lived. State legislatures kept or passed wide-ranging discriminatory laws, against Black Americans, for sure, and also against other minorities — Asian immigrants were explicitly prohibited from owning land, for example — and all women. By the early twentieth century, there were state laws against mixed-race marriages, against contraception, against integrated schools and housing, against abortion.

World War II changed the equation. Lawmakers had both to adjust to the demands of the minorities and women who had fought in the war and had kept the factories and fields operating, and to counter communists’ charges that American “democracy” sure didn’t look as equal as communism. To address discriminatory state laws, they turned to the Federal government.

After World War II, under Chief Justice Earl Warren and Chief Justice Warren Burger (both appointed by Republicans), the Supreme Court set out to make all Americans equal before the law. They tried to end segregation through the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Tоpеkа, Kаnsаs, decision prohibiting racial segregation in public schools. In 1965, they protected the right of married couples to use contraception. In 1967, they legalized interracial marriage. In 1973, with the Roe v. Wade decision, they tried to give women control over their own reproduction by legalizing abortion.

Justices in the Warren and Burger courts protected these Civil Rights by arguing that the Fourteenth Amendment required the Bill of Rights to apply to state governments as well as to the Federal government. This is known as the “incorporation doctrine,” but the name matters less than the concept: it said that states cannot abridge an individual’s rights, any more than the Federal government can. This doctrine dramatically expanded Civil Rights.

But opponents of the new decisions insisted that the court was engaging in “judicial activism,” taking away from voters the right to make their own decisions about how society should work. That said that justices were “legislating from the bench.” They insisted that the Constitution is limited by the views of its Framers and that the government can do nothing that is not explicitly written in that 1787 document. They wanted to replace the court’s interpretation of the Constitution with a view that preserved its “original” intent.

The 1987 fight over President Ronald Reagan’s nominee for the Supreme Court, originalist Robert Bork, was the first salvo in the attempt to roll back the court’s expansion of Civil Rights. Bork was extreme for his day — famously saying that the Constitution did not protect the right for married people to use birth control, for example — and six Republicans joined the Democrats to oppose him. But the swing toward originalism was underway.

Now, finally, thanks to the three Supreme Court justices nominated by Donald Trump and confirmed thanks to then–Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s breaking of the filibuster, the Republicans have cemented an originalist view of the Constitution on the Supreme Court. Their doctrine will send authority for Civil Rights back to the states to wither or thrive as different legislatures see fit.

In Texas, the legislature has taken away from its citizens a right guaranteed by the Constitution, and the Supreme Court has declined to assert Federal power to stop it.

In a partial dissent from the decision, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that “the clear purpose and actual effect of S.B. 8 has been to nullify this Court’s rulings,” and quoted an 1809 decision that said, “[i]f the legislatures of the several states may, at will, annul the judgments of the courts of the United States, and destroy the rights acquired under those judgments, the constitution itself becomes a solemn mockery.” Roberts warned his colleagues that “the role of the Supreme Court in our constitutional system…is at stake.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor was blunter. Texas has launched “a brazen challenge to our Federal structure,” she said, one that “echoes the philosophy of John C. Calhoun, a virulent defender of the slaveholding South who insisted that States had the right to ‘veto’ or ‘nullif[y]’ any Federal law with which they disagreed.”

Under this old system, what Civil Rights will be off-limits?

The court’s “choice to shrink from Texas’ challenge to Federal supremacy will have far-reaching repercussions,” Sotomayor wrote. “I doubt the Court, let alone the country, is prepared for them.”

Jеrеmy Hоgаn

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics