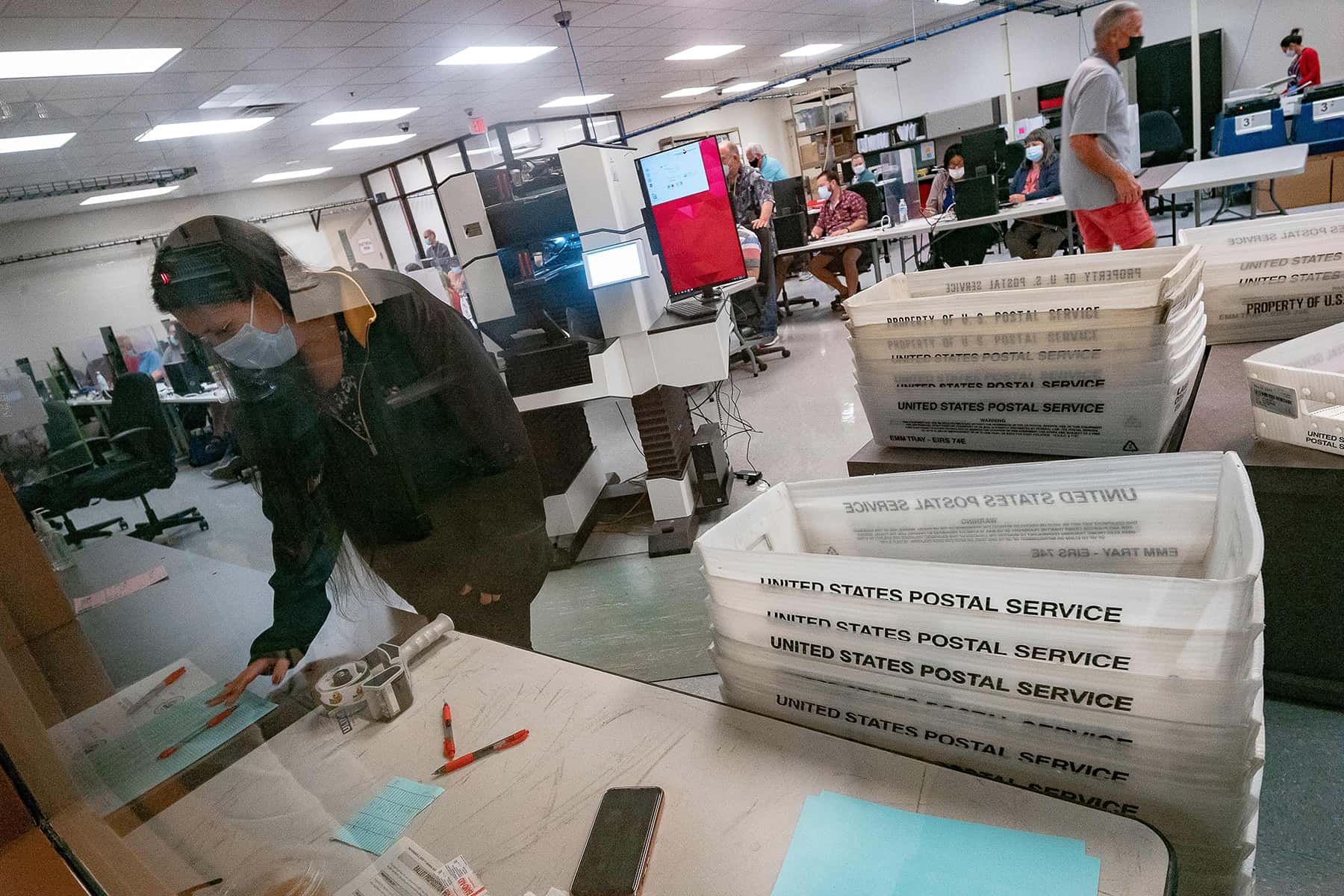

By a 6 to 3 vote, the Supreme Court handed down Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee on July 1 saying that the state of Arizona did not violate the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA) with laws that limited ballot delivery to voters, family members, or caregivers, or when it required election officials to throw out ballots that voters had cast in the wrong precincts by accident.

The fact that voting restrictions affect racial or ethnic groups differently does not make them illegal, Justice Samuel Alito wrote. “The mere fact that there is some disparity in impact does not necessarily mean that a system is not equally open or that it does not give everyone an equal opportunity to vote.”

The court also suggested that concerns about voter fraud—which is so rare as to be virtually nonexistent—are legitimate reasons to restrict voting. We are reliving the Reconstruction years after the Civil War.

That war had changed the idea of who should have a say in American society. Before the war, the ideal citizen was a White man, usually a property owner. But those were the very people who tried to destroy the country, while during the war, Black Americans and women, people previously excluded from politics, gave their lives and their livelihoods to support the government.

After the war, when White southerners tried to reinstate laws that returned the Black population to a position that looked much like enslavement, Congress in 1867 gave Black men the right to vote for delegates to new state constitutions. Those new constitutions, in turn, gave Black men the right to vote.

In order to stop voters from ratifying the new constitutions, White southerners who had no intention of permitting Black Americans to gain rights organized as the Ku Klux Klan to terrorize voters. While they failed to prevent states from ratifying the new constitutions, the KKK continued to beat, rape, and murder Black voters in the South.

So, in 1870, Congress established the Department of Justice to defend Black rights in the South. It also passed a series of laws that made it a federal crime to interfere with voting and with the official duties of an elected officer. And it passed, and the states ratified, the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, declaring that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Immediately, White Americans determined to stop Black participation in government turned to a new argument. During the Civil War, the Republican Party had not only expanded Black rights, but had also invented the nation’s first national taxation. For the first time, how people voted directly affected other people’s pocketbooks.

In 1871, White southerners began to say that they did not object on racial grounds to Black voting, but rather on the grounds that formerly enslaved men were impoverished and were electing to office men who promised to give them things — roads, for example, and schools and hospitals — to be paid for with tax dollars. Because White men were the only ones with property in the postwar South, such legislation would redistribute wealth from White men to Black people. It was, they charged, “socialism.”

In 1876, White southerners reclaimed control of the last remaining states they had not yet won by insisting they were “redeeming” their states from the corruption created when Black voters elected leaders who would use tax dollars for public programs.

In 1890, a new constitution in Mississippi, which at the time was about 58% Black, restricted voting not on racial grounds but through a poll tax and a “literacy” test applied against Black voters alone. Mississippi led the way for new restrictions across the country. Although Black and Brown Americans continually challenged the new Jim and Juan Crow laws that silenced them, voting registration for people of color fell into single digits.

These laws stayed in place for 75 years. Then, in 1965, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, designed to undo voter suppression laws once and for all. The VRA worked. In Mississippi in 1965, just 6.7% of eligible Black voters were registered to vote. Two years later, that number was 59.8%, although there was still a 32-point gap in registration between Blacks and Whites. By 1988, that gap had narrowed to 6.3%, and in 2012, 90.2% of eligible Black residents were registered compared to 82.4% of non-Hispanic Whites.

The Voting Rights Act was considered so important that just 15 years ago, in 2006, Congress voted almost unanimously to reauthorize it. But the Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Roberts, who has long disliked the VRA, has chipped away at the law, cutting deeply into it in 2013 with the Shelby County v. Holder decision. And now, with three new justices appointed by former president Trump, the court has weakened it further.

To what end are we returning to the 1890s? The restrictive voting measures passed by Republican-dominated legislatures are designed to keep Republicans in power. Today that means allegiance to former president Trump, whose Trump Organization and Trump Payroll Corporation were indicted by a New York grand jury on July 1, along with Trump Organization chief financial officer Allen Weisselberg, on 15 felony counts, including a scheme to defraud, conspiracy, grand larceny, criminal tax fraud, and falsifying business records.

The indictment alleges that the schemes involve federal, as well as state and local, crimes. New York Attorney General Letitia James emphasized that the investigation is not over. Republican lawmakers are lining up behind the former president so closely that last night, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) threatened to take away the committee assignments of anyone agreeing to work on the select committee to investigate the events of January 6 that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) is putting together after Senate Republicans filibustered the creation of a bipartisan independent committee.

McCarthy’s declaration prompted Representative Adam Kinzinger (R-IL), who appears appalled at the direction his party has taken, to respond “Who gives a s–t?” He added: “I do think the threat of removing committees is ironic, because you won’t go after the space lasers and White Supremacist people but those who tell the truth.”

Representative Liz Cheney (R-WY) nonetheless said she was “honored” to join the committee, along with seven Democrats. While it is unclear if McCarthy will add more Republicans, it will now get underway. The committee includes House Intelligence Committee chair Adam Schiff (D-CA), and Representative Jamie Raskin (D-MD), both of whom showed extraordinary ability to assess huge amounts of material when they managed Trump’s impeachment trials.

That the Republicans have fought so hard against an investigation of the January 6 insurrection suggests we might well learn things that reflect poorly on certain lawmakers. So, the developments puts the American people in the position of watching as a political party, lined up behind a man now in legal jeopardy, who might be involved in an attack on our government, tries to cement its hold on power.

“The decision by the Supreme Court undercuts voting rights in this country,” President Biden said, “and makes it all the more crucial to pass the For the People Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act to restore and expand voting protections. Our democracy depends on it.”

Оlіvіеr Tоurоn

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics