The economy has boomed under President Joe Biden, putting to rest the lie to the old trope that Democrats do not manage the economy as well as Republicans.

This should not come as a surprise to anyone. The economy has performed better under Democrats than Republicans since at least World War II. CNN Business reported that since 1945, the Standard & Poor’s 500 — a market index of 500 leading U.S. publicly traded companies — has averaged an annual gain of 11.2% during years when Democrats controlled the White House, and a 6.9% average gain under Republicans.

In the same time period, gross domestic product grew by an average of 4.1% under Democrats, 2.5% under Republicans. Job growth, too, is significantly stronger under Democrats than Republicans.

“[T]here has been a stark pattern in the United States for nearly a century,” wrote David Leonhardt of the New York Times last year, “The economy has grown significantly faster under Democratic presidents than Republican ones.”

The persistence of the myth that Democrats are bad for the economy is an interesting example of the endurance of political rhetoric over reality.

It began in the postwar years: the post–Civil War years, that is. Before the Civil War, moneyed men tended to support the Democrats, for the big money in the country was in the cotton enterprises of the leading enslavers in the American South, and they expressed their political power through the Democratic Party, which promised to protect and nurture the institution of human enslavement.

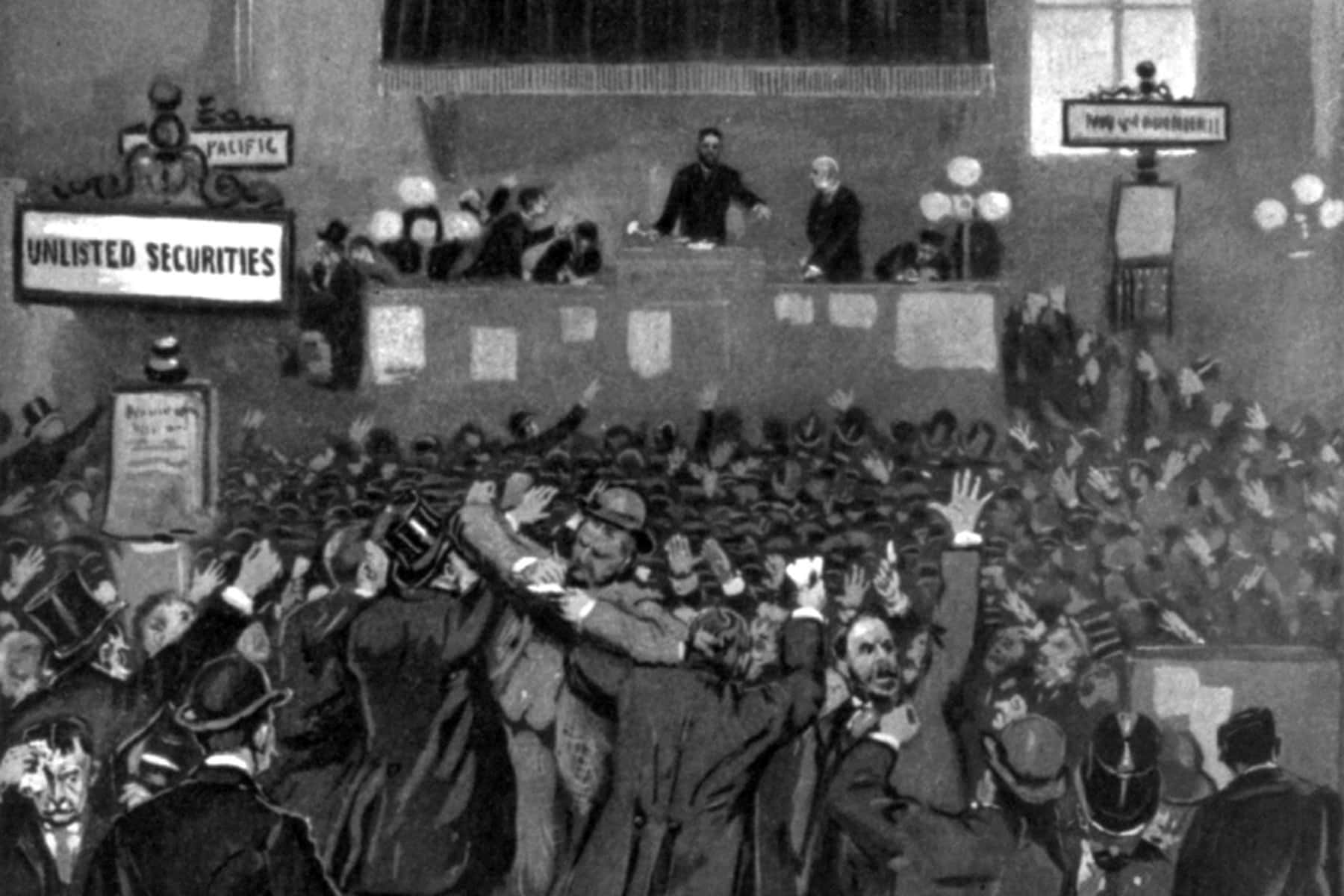

Indeed, when soldiers of the Confederacy fired on Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, in April 1861, it was not clear at all whether bankers in New York City would back the United States or the southern rebels. After all, the South was the wealthiest region of the country, and the North had just undergone the devastating Panic of 1857. Southern leaders laughed that without the South, northerners would starve.

The economic policies of the war years, including our first national money, national taxation, state universities, and deficit spending, created a newly booming industrial North, but many moneyed men resented the Republican policies they felt offered too much to poor Americans (the Homestead Act was a special thorn in their sides because it meant that western lands taken from Indigenous Americans would no longer be sold to bring money into the Treasury but would be given away to poor farmers). When the government established national banks, establishing regulations over the lucrative banking industry, state bankers were unhappy.

Whether moneyed men would stay loyal to Lincoln in 1864 was an open question. In the end, they did, but their loyalty after the war was up for grabs.

Democrats’ postwar financial policies drove moneyed men to give their allegiance to the Republican Party. Eager to make inroads on the Republicans’ popularity, northern Democrats pointed out that the economic gains of the war years had gone to those at the top of the economy, and they called for financial policies that would level the playing field. Notably, they wanted to pay the interest on the war debt with greenbacks rather than gold, which would make the bonds significantly less valuable. The alteration would also establish that political parties could take office and change government financial engagements after they were already in force.

Republicans recognized that if a change of this sort were legitimate, the government’s ability to borrow in the future — say, to put down another rebellion — would be hamstrung. They were so worried that in 1868, they protected the debt in the Fourteenth Amendment itself, saying: “The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned.”

When it looked as if a coalition including the Democrats might win the presidency in 1872, leaders from Wall Street publicly threw their weight behind the Republicans, and in exchange, the Republicans backed away from supporting the workers who had made up their initial voting base.

Southern White Supremacists had begun to charge that permitting poor men to vote would lead to a redistribution of wealth as they voted for roads and schools and hospitals that could only be paid for by tax levies on those with property. Such a system was, they charged, “socialism.”

While Southern Whites directed their animosity toward their formerly enslaved Black neighbors, northerners of means adopted their ideas and language but targeted immigrants and organized workers. If those people came to control government and thus the economy, wealthier Americans argued, they would bring socialism to America, and the nation would never recover.

Increasingly, power shifted to wealthy industrialists who, after 1872, were represented by the Republican Party. They demanded high tariffs that protected their industries by keeping out foreign competition and thus permitted them to collude to raise prices on consumers. By the 1880s, Republican senators were openly serving big business; even the staunchly Republican Chicago Tribune lamented in 1884 that “[b]ehind every one of half of the portly and well-dressed members of the Senate can be seen the outlines of some corporation interested in getting or preventing legislation.”

As money moved to the top of the economy, Democrats pushed back, calling for government to restore a level playing field between workers and their employers. As they did so, Republicans howled that Democrats advocated socialism.

Finally, after the spectacularly corrupt administration of Republican Benjamin Harrison, which businessmen had called “beyond question the best business administration the country has ever seen,” the unthinkable happened. In the election of 1892, for the first time since the Civil War, Democrats took control of the White House and Congress. They promised to rein in the power of big business by lowering the tariffs and loosening the money supply. This, Republicans insisted, meant financial ruin.

Republicans warned that capital would flee the markets and urged foreign investors — on whom the economy depended — to take their money home. They predicted a financial crash as the Democrats embraced socialism, anarchism, and labor organization. Money flowed out of the country as the outgoing Harrison administration poured gasoline on the fires of media fears and refused to act to try to turn the tide. Harrison’s secretary of the Treasury, Charles Foster, said his job was only to “avert a catastrophe” until March 4, when Democratic president Grover Cleveland would take office.

He did not quite manage it. The bottom fell out of the economy on February 17, when the Reading Railroad Company could not make its payroll, sparking a nationwide panic. The stock market collapsed. And yet the Harrison administration refused to do anything until the day Cleveland took office, when Foster helpfully announced the Treasury “was down to bedrock.”

To Cleveland fell the Panic of 1893, with its strikes, marchers, and despair, all of which opponents insisted was the Democrats’ fault. In the midterm election of 1894, Republicans showed the statistics of Cleveland’s first two years and told voters that Democrats destroyed the economy. Voters could restore the health of the nation’s economy by electing Republicans again. In 1894, voters returned Republicans to control of the government in the biggest midterm landslide in American history, and the image of Democrats as bad for the economy was cemented.

From then on, Republicans portrayed Democrats as weak on the economy. When the next Democratic president to take office, Woodrow Wilson, undermined the tariff as soon as he took office, replacing it with an income tax, opponents insisted the Revenue Act of 1913 was inaugurating the country’s socialistic downfall. When Democratic president Franklin Delano Roosevelt pioneered the New Deal, Republicans saw socialism. Over the past century, that rhetoric has only grown stronger.

And yet, of course, it has been Republican economic policies that opened up the possibility for Democrats to try new approaches to the economy, to make it serve all Americans, rather than a favored few. As FDR put it: “It is common sense to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something. The millions who are in want will not stand by silently forever while the things to satisfy their needs are within easy reach.”

In the end, that’s what the economists Leonhardt interviewed last year think is behind Democrats’ ability to manage the economy better than Republicans. Republicans tend to cling to abstract theories about how the economy works—theories about high tariffs or tax cuts, for example, which tend to concentrate wealth upward — while Democrats are more pragmatic, willing to pay attention to facts on the ground and to historical lessons about what works and what does not.

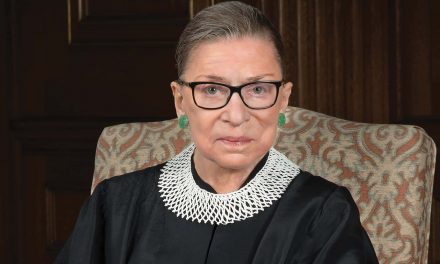

Library of Congress

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics