On August 21, 1831, enslaved American Nat Turner led about 70 of his enslaved and free Black neighbors in a rebellion to awaken his White neighbors to the inherent brutality of slaveholding and the dangers it presented to their own safety.

Turner and his friends traveled from house to house in their neighborhood in Southampton County, Virginia, freeing enslaved people and murdering about 60 of the White men, women, and children they encountered. Their goal, Turner later told an interviewer, was “to carry terror and devastation wherever we went.”

State militia put down the rebellion in a couple of days, and both the legal system and White vigilantes killed at least 200 Black Virginians, many of whom were not involved in Turner’s bid to end enslavement. Turner himself was captured in October, tried in November, sentenced to death, and hanged.

But White Virginians, and White folks in neighboring southern states, remained frightened. Turner had been, in their minds, a well-treated, educated enslaved man, who knew his Bible well and seemed the very last sort of person they would have expected to revolt. And so they responded to the rebellion in two ways. They turned against the idea that enslavement was a bad thing and instead began to argue that human enslavement was a positive good.

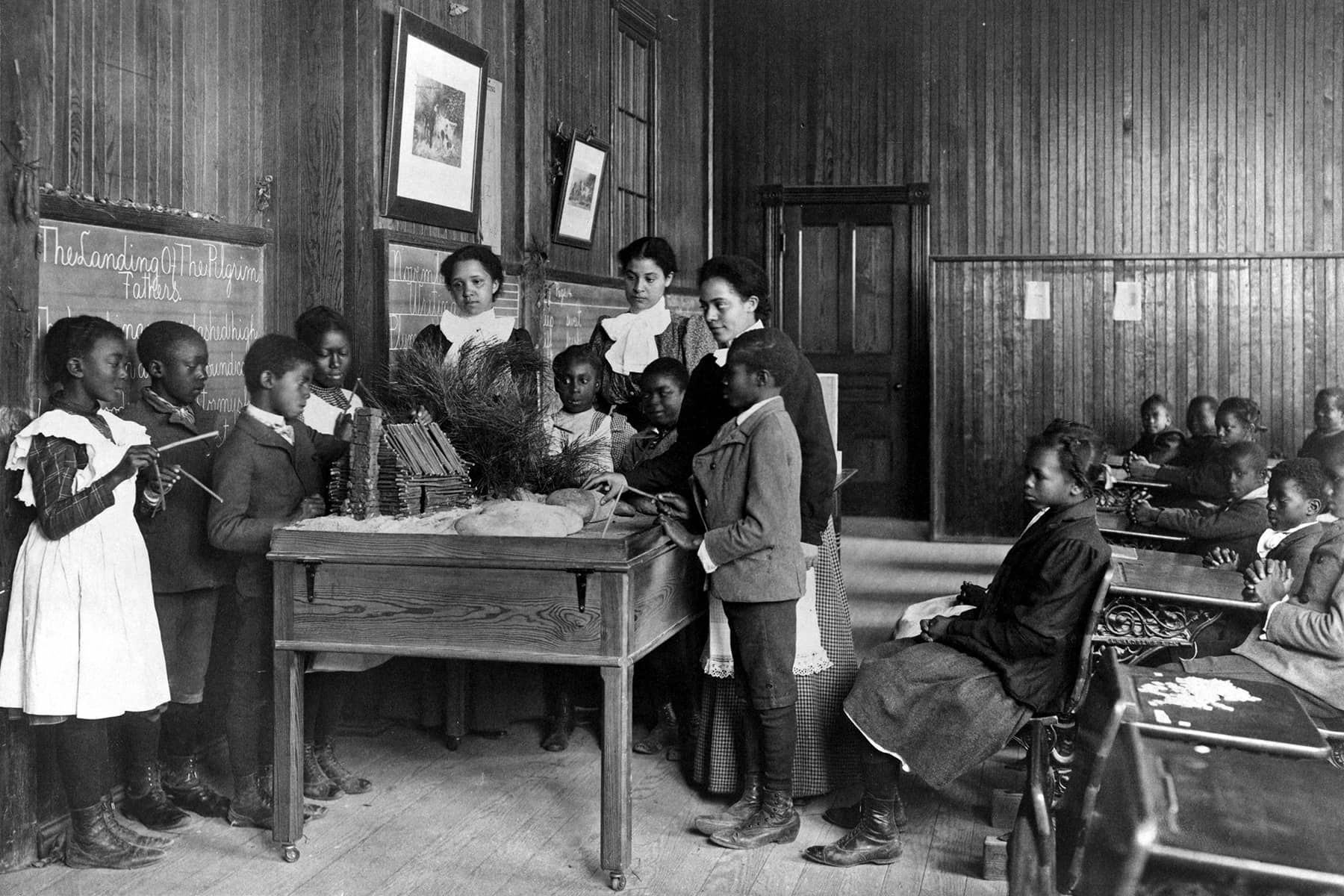

And states across the South passed laws making it a crime to teach enslaved Americans to read and write.

Denying enslaved Black Americans access to education exiled them from a place in the nation. The Framers had quite explicitly organized the United States not on the principles of religion or tradition, but rather on the principles of the Enlightenment: the idea that, by applying knowledge and reasoning to the natural world, men could figure out the best way to order society. Someone excluded from access to education could not participate in that national project. Instead, that person was read out of society, doomed to be controlled by leaders who marshaled propaganda and religion to defend their dominance.

In 1858, South Carolina Senator James Henry Hammond explained that society needed “a class to do the menial duties, to perform the drudgery of life. That is, a class requiring but a low order of intellect and but little skill.”

But when they organized in the 1850s to push back against the efforts of elite enslavers like Hammond to take over the national government, members of the fledgling Republican Party recognized the importance of education. In 1859, Illinois lawyer Abraham Lincoln explained that those who adhered to the “mud-sill” theory “assumed that labor and education are incompatible; and any practical combination of them impossible … According to that theory, the education of laborers, is not only useless, but pernicious, and dangerous.”

Lincoln argued that workers were not simply drudges but rather were the heart of the economy. “The prudent, penniless beginner in the world, labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land, for himself; then labors on his own account another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him.” He tied the political vision of the Framers to this economic vision. In order to prosper, he argued, men needed “book-learning,” and he called for universal education. An educated community, he said, “will be alike independent of crowned-kings, money-kings, and land-kings.”

When they were in control of the federal government in the 1860s, Republicans passed the Land Grant College Act, funding public universities so that men without wealthy fathers might have access to higher education. In the aftermath of the Civil War, Republicans also tried to use the federal government to fund public schools for poor Black and White Americans, dividing money up according to illiteracy rates.

But President Andrew Johnson vetoed that bill on the grounds that the federal government had no business protecting Black education; that process, he said, belonged to the states — which for the next century denied Black and Brown people equal access to schools, excluding them from full participation in American society and condemning them to menial labor.

Then, in 1954, after decades of pressure from Black and Brown Americans for equal access to public schools, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren, a former Republican governor of California, unanimously agreed that separate schools were inherently unequal, and thus unconstitutional. The federal government stepped in to make sure the states could not deny education to the children who lived within their boundaries.

And now, in 2022, we are in a new educational moment. Between January 2021 and January 2022, the legislatures of 35 states introduced 137 bills to keep students from learning about issues of race, LBGTQ+ issues, politics, and American history. More recently, the Republican-dominated legislature of Florida passed the Stop the Wrongs to Our Kids and Employees (Stop WOKE) Act, tightly controlling how schools and employee training can talk about race or gender discrimination.

Republican-dominated legislatures and school districts are also purging books from school libraries and notifying parents each time a child checks out a book. Most of the books removed are by or about Black people, people of color, or LGBTQ+ individuals.

Both sets of laws are likely to result in teachers censoring themselves or leaving the profession out of concern they will inadvertently run afoul of the new laws, a disastrous outcome when the nation’s teaching profession is already in crisis. School districts facing catastrophic teacher shortages are trying to keep classrooms open by doubling up classes, cutting the school week down to four days, and permitting veterans without educational training to teach — all of which will likely hurt students trying to regain their educational footing after the worst of the pandemic.

This, in turn, adds weight to the move to divert public money from the public schools into private schools that are not overseen by state authorities. In Florida, the Republican-controlled legislature has dramatically expanded the state’s use of vouchers recently, arguing that tying money to students rather than schools expands parents’ choices while leaving unspoken that defunded public schools will be less and less attractive.

In June, in Carson v. Makin, the Supreme Court expanded the voucher system to include religious schools, ruling that Maine, which provides vouchers in towns that do not have public high schools, must allow those vouchers to go to religious schools as well as secular ones. Thus tax dollars will support religious schools.

In 2022, it seems worth remembering that in 1831, lawmakers afraid that Black Americans exposed to the ideas in books and schools would claim the equality that was their birthright under the Declaration of Independence made sure their Black neighbors could not get an education.

Еvеrеtt Collеction

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics