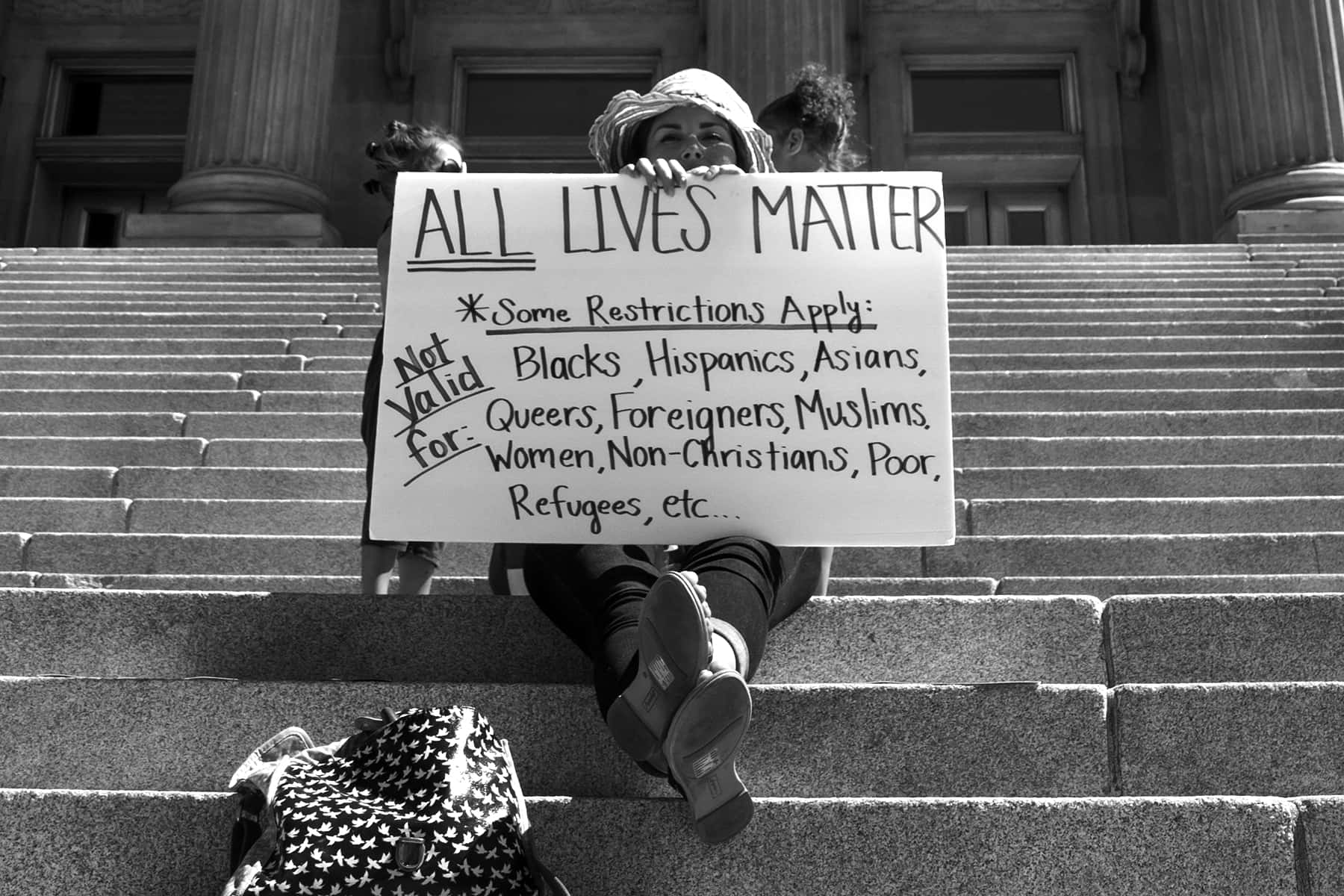

“White people who say “All Lives Matter” are the equivalent of the Founding Fathers writing “All men are created equal” while owning slaves.” – Social Media Meme

A conversation that will never take place:

Person 1: I’m going to make sure this year that I show my support for breast cancer awareness month.

Person 2: Hey you really should not make a statement about breast cancer awareness, it devalues all other cancers. All Cancers Matter.

A conversation you’ve probably heard:

Person 1: I’m going to make sure this year that I show my support for the Black Lives Matter Movement.

Person 2: Hey you really should not make a statement like black lives matter, it is kinda racist. You should say, All Lives Matter.

Back in 1968 the legendary singer James Brown released a song with the following lyrics:

Say it loud! I’m black and I’m proud

Say it louder! I’m black and I’m proud

Look a-here!

Some people say we got a lot of malice, some say it’s a lotta nerve

But I say we won’t quit movin’ until we get what we deserve

We’ve been ‘buked and we’ve been scorned

We’ve been treated bad, talked about as sure as you’re born

But just as sure as it take two eyes to make a pair, huh!

Brother we can’t quit until we get our share

The song was controversial. White people were upset and called it racist. Many black people adopted it as their anthem. I was only three years old but I remember years later hearing my favorite aunt playing it loudly and proudly on her stereo. What made it controversial? Black people were saying that black was beautiful, cool, and something to be proud of. It was not appreciated by many whites because they felt black people were getting a little too “uppity.”

Since the phrase black lives matter came into our consciousness in 2013, white people have been incensed that black people are getting “uppity” again. How dare black people say something positive about themselves? America has been saying bad stuff about black people for so long that it almost seems antithetical to say something positive. Tell me what you learned in school about black people that was positive? I learned next to nothing that was positive about black people in school. Sure I learned about Dr. King, Rosa Parks, Booker T. Washington, and George Washington Carver, but nothing positive other than the fact that we fought a Civil Rights Movement and along the way had a handful of well-thought of black people. Nothing positive about us as a group.

I often ask a simple question that leads to perplexed looks on the faces of people. After the Civil War Amendments giving blacks freedom from slavery, citizenship rights and black men the right to vote, why did we need a Civil Rights Movement less than a century later? Weren’t we living in a society that promoted itself as in favor of freedom, justice and liberty for all?

No group has seen their lives so consistently devalued in laws, and customs within this country as black people. In 1641 The Massachusetts Body of Liberties, wrote the first legal code established by European colonists in New England, legalizing the institution of slavery. Massachusetts thus became the first state to officially legalize slavery although the practice was in place among the British from the time the first Africans arrived in 1619. The Dutch had previously held Africans captive in the same region going back as far as the 1520s. The 1619 Project by the New York Times documented the beginnings of this journey in the British colonies.

“In August of 1619, a ship appeared on this horizon, near Point Comfort, a coastal port in the British colony of Virginia. It carried more than 20 enslaved Africans, who were sold to the colonists. America was not yet America, but this was the moment it began. No aspect of the country that would be formed here has been untouched by the 250 years of slavery that followed.”

In 1662 a Virginia law decreed that children “shall be bond or free according to the condition of the mother.” This law made the children of an enslaved mother slaves for life and would soon would be adopted throughout the thirteen colonies.

For many years I’ve argued that people should read the Emancipation Proclamation instead of reading about it. Lincoln’s January 1, 1863 proclamation did not come as a surprise to the South because he issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862 to warn the South about his intentions. The following words described the specifics of where the “freeing of the slaves” applied.

“the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth[)], and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.”

It was never intended to free all of the Africans held captive in the country. In 1860 the last US Census done prior to the Civil War showed that Delaware held 1,798 African captives, Kentucky held 225,483 captive, Missouri held 114,931 captive, Maryland held 87,189 captive. Only ten of the eleven Confederate states were mentioned in the proclamation. Tennessee was excluded and they held 275,719 Africans in bondage prior to the war. The state had been captured by Union troops and was considered part of the Union again by Lincoln. The Africans in each of the places exempted were not given their freedom until the Thirteenth Amendment passed in December 1865, eight months after the war ended and Lincoln’s assassination.

Lincoln stuck this part into the Emancipation Proclamation that no one seems to acknowledge. “And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defense; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.” This allowed him to begin recruiting black men for the Union Army and Navy. Over 200,000 would help turn the tide of the war back in favor of the Union. It also assumed that these freed Africans would be violent for the sake of being violent and that they had to be mandated to work, lest they sit around and be lazy like the people who’d forced them to work for free their entire lives.

Two weeks later Confederate President Jefferson Davis responded to the Emancipation Proclamation in a speech to the Confederate Congress on January 13, 1863 saying the following:

“We may well leave it to the instincts of that common humanity which a beneficent Creator has implanted in the breasts of our fellow-men of all countries to pass judgment on a measure by which several millions of human beings of an inferior race, peaceful and contented laborers in their sphere, are doomed to extermination, while at the same time they are encouraged to a general assassination of their masters by the insidious recommendation ‘to abstain from violence unless in necessary self-defense.’ Our own detestation of those who have attempted by the most execrable measure recorded in the history of guilty man is tempered by a profound contempt for the impotent rage which it discloses.”

He saw it as a call for rebellion by the captive Africans. He also stated his believe that it “doom[ed]” black Americans “to extermination.” Despite their valiant efforts, the black soldiers had to fight for equal pay. Abolitionist leader Frederick Douglas who supported black Union troops was upset that they were paid less than white troops. On August 1, 1863, he announced that he would no longer recruit troops for the Union Army. “When I plead for recruits, I want to do it with all my heart. I cannot do that now.” Lincoln met with Douglas and insisted that “lower pay was a “necessary concession to smooth the way” toward equal pay eventually. Douglas argued that “there is no power on earth that can deny … the right to citizenship” to black men who fought for the Union. Black soldiers were paid $10 per month with a onetime $3 deduction for the cost of their uniforms. White soldiers were paid $13 per month and received free uniforms. In June 1864, Congress granted equal pay for black soldiers which was applied retroactively.

My great-grand father’s great grandfather served in a Colored troop unit during the war. Blacks who had escaped to Union camps were called “contrabands of war.” They were supposed to be protected by Union troops. The unit my ancestor served in had to stand in to protect these Africans that white Union troops refused to defend from Confederate troops and other whites in northern Mississippi.

Those of us who were supposedly free had to live under laws and customs that marginalized us and kept us in “our place.” We could be snatched off the streets, placed in shackles and sold “down the river” at any given moment. There was nothing free about being free if you had black skin. We would wander the land looking for opportunities and be turned away by whites who wanted to keep all of the material possessions to themselves. America gave us forty acres and a mule after the war and then took it back.

One of the ugliest events during the war occurred at Fort Pillow, Tennessee on April 12, 1864. The Fort Pillow Massacre left over 300 black soldiers dead even though they had surrendered along with their white colleagues. Confederate and Union witness accounts attest that the black troops were massacred by Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s men after surrendering. He would later be elected the Ku Klux Klan’s first “Grand Wizard.”

The Ku Klux Klan terrorized blacks for seeking to exercise their right to vote, running for public office, and serving on juries after they had been granted these rights by the Fifteenth Amendment. These terrorists were so violent that Congress passed the KKK or Civil Rights Act of 1871, empowering President Grant to use the military to combat those members who conspired to deny equal protection of the laws. In 1883 the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously held that it was unconstitutional for the federal government to penalize crimes such as assault and murder, basically opening the door for rampant murders of blacks across the country. Lynchings increased exponentially after this ruling.

The Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama described lynching in America in this way.

“During the period between the Civil War and World War II, thousands of African Americans were lynched in the United States. Lynchings were violent and public acts of torture that traumatized black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials. These lynchings were terrorism. “Terror lynchings” peaked between 1880 and 1940 and claimed the lives of African American men, women, and children who were forced to endure the fear, humiliation, and barbarity of this widespread phenomenon unaided.”

The period after the Civil War ended and the beginnings of the Civil Rights Movement is the least known part of black people’s history in this country. The resilience and demands for justice by black people over that ninety years would tell us a lot about what the Black Lives Matter Movement is about. We were never simply victims of American racism, we fought it tooth and nail just as we are now.

These were some the ugliest years in the nation’s history. Blacks were slaughtered in race riots by whites intent on making sure they were never afforded confidence in knowing they were free from mob violence at the hands of white people throughout the country. Lynch mobs freely roamed the country, murdering blacks any time they chose too with no punishments being handed out by “the law.” Segregated public spaces became the norm because white people wanted to send a clear message that they were superior to us. The federal, state and local governments discriminated against black people and gave white people huge advantages to make sure they stayed ahead of blacks in every sector of society.

Our children have been denied the opportunities afforded white children by an education system that has always limited their full potential. We have been disrespected, beaten, and killed by police for most of our time in America and drawn into a criminal justice system that is anything but just. We have stood by and witnessed police killing black people with impunity while whites who claim to not be racist, blame the victims time and time again. We have fought the internalized racism that makes it difficult for many of us to see ourselves in a positive light. We have been the last hired and first fired for so long that we know when it’s coming. Our lives have never mattered in America. Some of us have been fortunate enough to gain some of the riches of America through hard work, but we always tell our children that they need to be better than white children to gain the same opportunities in life. Our lives are never secure, even when we have material wealth. These things are the essence of why we have to shout that “Black Lives Matter.” We can’t say it quietly because white people won’t listen unless we raise our collective voices to demand our respect.

Those who find it so hard to accept and understand the rallying cry “Black Lives Matter” need to re-educate themselves on American history before they open their mouths and show how little they know about the country they call home. It is the height of disrespect to tell us that “all lives matter” when this nation has, since its inception, proven to us that only our bodies matter, not our lives as living, breathing human beings. How can all lives matter when ours don’t?

It’s never too late to learn the truth. The eloquent words of my personal hero, Frederick Douglas, spoken nearly two hundred years ago tells us about ourselves and how far we still need to go. I believe he would be very disappointed to know that the battle continues in 2020.

“You invite to your shores fugitives of oppression from abroad, honor them with banquets, greet them with ovations, cheer them, toast them, salute them, protect them, and pour out your money to them like water; but the fugitives from your own land you advertise, hunt, arrest, shoot and kill. You glory in your refinement and your universal education yet you maintain a system as barbarous and dreadful as ever stained the character of a nation — a system begun in avarice, supported in pride, and perpetuated in cruelty…You are all on fire at the mention of liberty for France or for Ireland; but are as cold as an iceberg at the thought of liberty for the enslaved of America…” – Frederick Douglas, “What to the Slave is the 4th of July?” Speech delivered July 5, 1852