Not long ago I began to more actively pay attention to the city I’ve spent most of my life in. I began to see things that had been right in front of me for years that I simply found no reason to pay close attention to.

My mind is wired in such a way that I notice patterns. I don’t understand why that is the case, but it has helped me to see things that other people don’t necessarily see. There are things that are right in front of us everyday that we mostly ignore or pay little attention to.

Milwaukee is full of things and places that we pay little to no attention to. There are things in Milwaukee that are bright and shiny and constantly fawned over by residents and visitors to the city. We have one of the most unique art museums in the world sitting right on our lakefront for the world to see. Hollywood paid attention to this beautiful building and featured it in Transformers 3. Spanish architect and sculptor Santiago Calatrava designed the 142,050-square-foot extension to the Milwaukee art museum, which was completed in 2001.

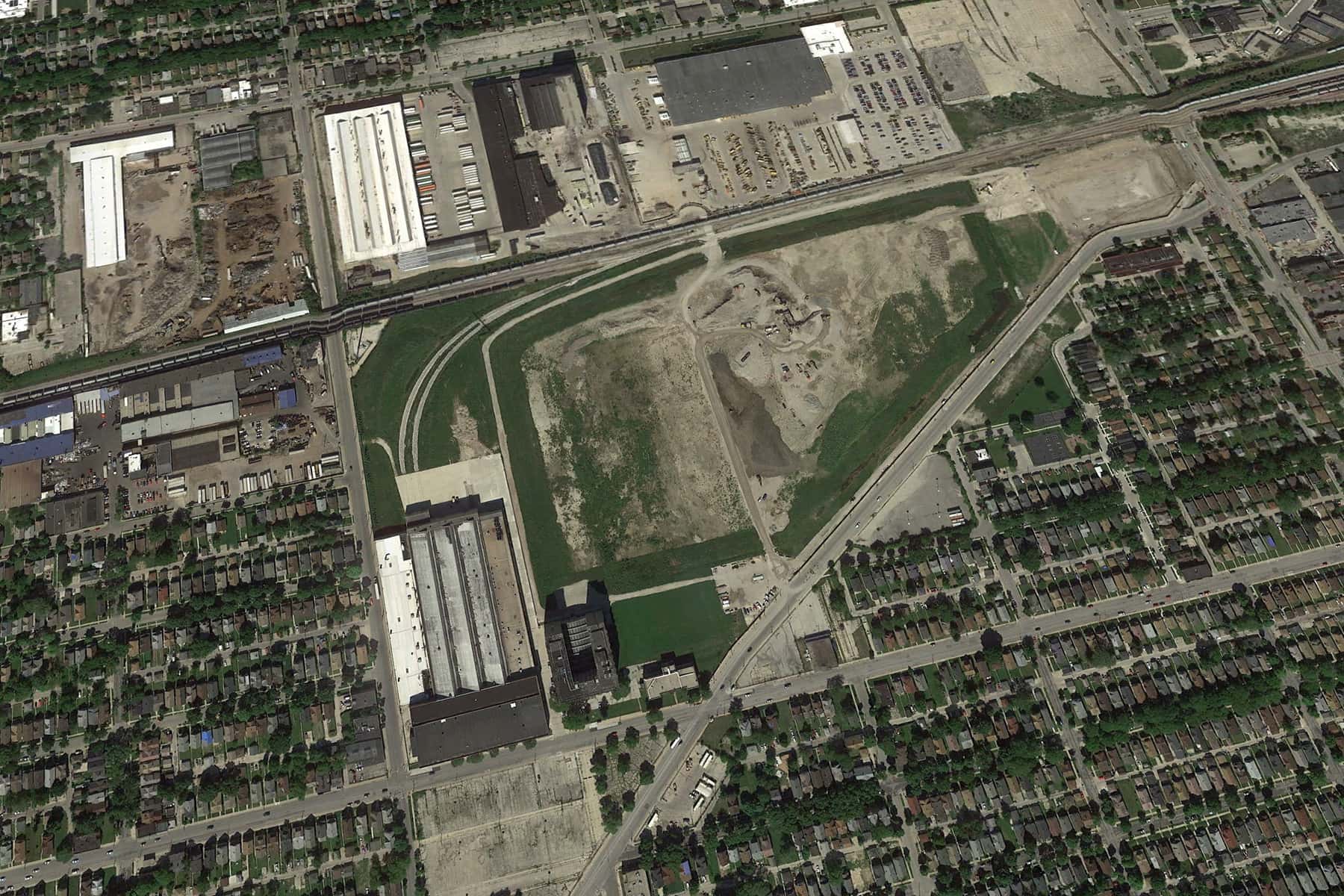

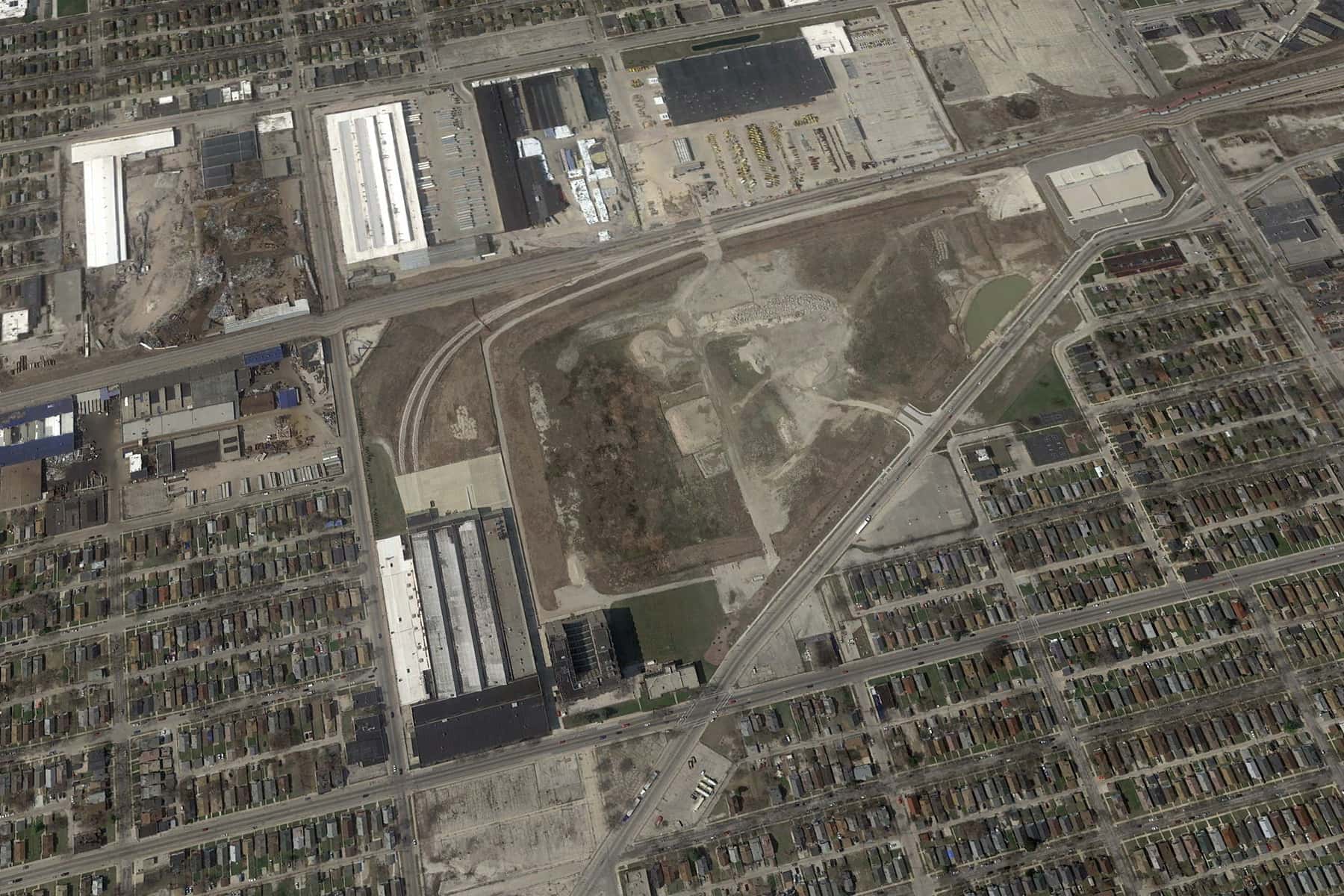

What’s forgotten is that back in 2010, Director Michael Bay chose a second location in Milwaukee to film at. The largely abandoned former site of Tower Automotive which was once home to A.O. Smith, and thousands of family supporting jobs, was also a spot used for filming.

This is one of those things that people don’t pay attention to in Milwaukee. The former site of A.O. Smith and what’s left of it are an eyesore on the north side of the city. It looks ugly, like a place that has been disinvested in, similar to the nearby 30th Street corridor industrial area.

I live fairly close to the old A.O. Smith facility and drive by it on a weekly basis. I remember as a middle school student having friends, with parents worked at the plant. It was a place that provided over 10,000 family supporting wage jobs at its peak. The iconic image of the old A.O. Smith were dozens of car and truck frames stacked on top of one another, waiting to be transported to facilities to build Buicks, Chevrolets, Chryslers, Cadillacs and many other cars and trucks.

A.O. Smith got their big break in 1906 when Henry Ford decided that standardizing frames would create the most efficient method for making his Model “N” vehicles. They had already designed the first of its kind pressed steel automotive frames in 1904. Ford asked A.O. Smith to provide 10,000 frames in four months. They retooled their plant by building the first continuous operation for car frames in the country and met the quick turnaround.

As more Americans became owners of automobiles, production of frames increased rapidly. During World War I, A.O. Smith produced bombs for the war effort and developed arc welding techniques that made them the worldwide technological leader in the field. They made welded pipes used in the petroleum industry beginning in the 1920s. During the Great Depression, A.O. Smith partnered with local breweries after the repeal of Prohibition to produce steel beer barrels. The company continued to innovate and made a variety of products for the military during World War II.

By the late 1970s, A.O. Smith had over 13,000 employees around the country, many of them at the Milwaukee plant and sales of over $800 million per year. They boasted about their Milwaukee plant as having produced “in excess of 93 million passenger car frames, over 33 million truck frames and more than 63 million sets of wheel suspension control arms. It currently supplies about 39 per cent of all full separate frames used in passenger cars and approximately 36 per cent of all truck frames manufactured in the U.S. and Canada.” The Automatic Frame Plant built in 1918 received recognition as a National Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark fifty-eight years later.

A.O. Smith employed about 8,000 people in 1970 in Milwaukee. They built the frames for practically every American made car. Only Allis Chalmers employed more people in the city. The industrial sector in Milwaukee drove the large influx of blacks seeking jobs in the city. Milwaukee saw its black population grow from 8,821 in 1940 to over 105,000 by 1970 as a result of manufacturing jobs like the ones at A. O. Smith.

The 148-acre plant on the north side of Milwaukee paid good wages and provided a standard of living for its employees, which was one of the best in the country for blacks. A.O. Smith was acquired by Tower Automotive in 1997 but employed only about 500 workers in 2004 after sending many jobs out of the country. Tower filed for bankruptcy in 2005 and shuttered the plant. Electrician Rick Wendling was the last employee at the site when they finally closed completely in November 2009.

After splitting the site in half after Tower closed, the city purchased the western half of the land and opened a location for the Department of Public Works in 2006. After a protracted legal battle, the city took possession of the eastern half of the property. The city of Milwaukee budgeted nearly $20 million for purchase, demolition, environmental remediation, and asbestos removal in 2009 of 82 acres of land at the site, planning to build a modern industrial park. In the end, the Common Council approved $34.6 million for the project, with $25.6 million coming from city funds. It has never really panned out.

The former headquarters of A.O. Smith stands vacant on the corner of Hopkins and 27th Street. I drive by often wondering why it still stands all these years later. I discovered that asbestos abatement costs for the building would have exceeded $15 million in 2009. The roof has been leaking for years and would be ridiculously expensive to repair. It is one of those things that we see everyday but pay no attention to. Thousands of people drive past per week, many of them with no memory of what used to be there. Little do they know that this building with its glass curtain walls, built in the 1930s was the engine that drove neighborhood development and pride for so many.

As I stopped in front of the building last year to take a close look, workers were removing a sign that promised to create a new industrial park at the site in 2020. Obviously it did not happen. In 2014, the mayor touted the Century City Business Park project during his “State of the city” speech. Rocky Marcoux, city development commissioner stated at the time, “We’ve worked with a number of prospects that look promising.” The one building on the site, the gleaming Century City I on the corner of 31st and Capitol Drive, is all that came out of the initiative to redevelop the site. Development firm General Capital Group promised to build two facilities on the site but never were able to find tenants for two buildings. It was expected that the two facilities would provide jobs for 900. The entire site of the former A.O. Smith plant now currently has five business operations that employs hundreds of people.

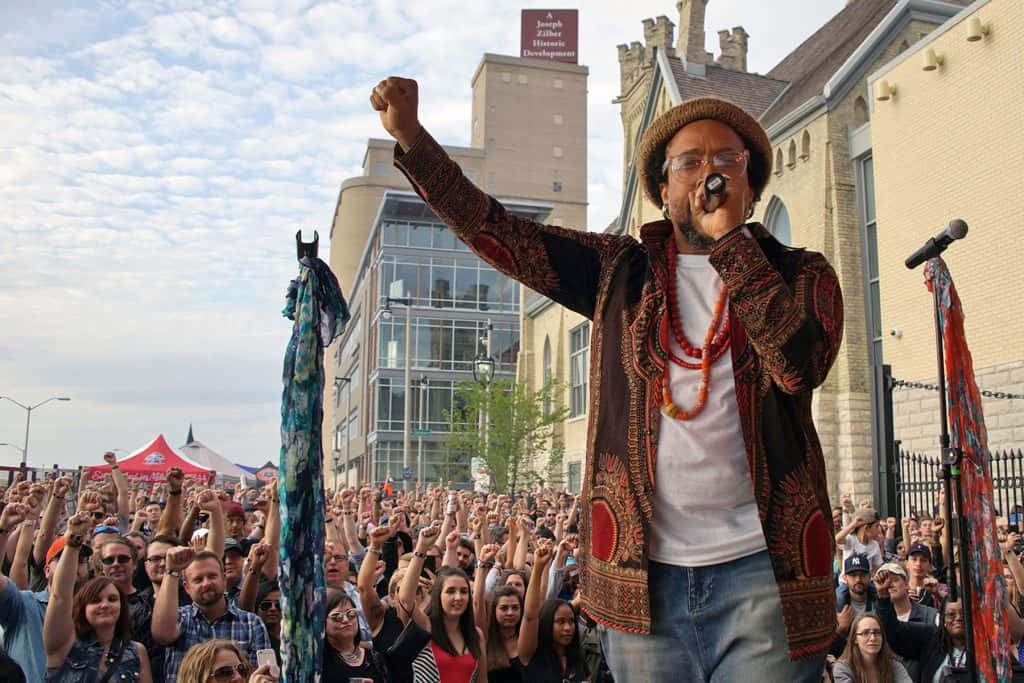

In October 2018 Good City Brewing acquired the Century City I building from the city of Milwaukee. The building which costs about $4.1 million to complete in 2016, was just sold to them for the equivalent of about $3.3 million according to reports in July 2018. They plan to move their company headquarters and warehouse operations into the Century City I building soon. Good City Brewing is best known for their sprawling brewery and taproom next to the Fiserv Forum Bucks arena downtown.

Each time I pass by the old site of A.O. Smith I’m reminded of a better time. I wonder how many people realize the devastation caused by the plant closing after years of downsizing and layoffs. The neighborhood around the plant is in terrible condition. Just a block away from the former headquarters on 27th Street are several boarded up homes. I see them all the time, but just started to actually pay attention.

As the city moves forward with so many new developments, the residents of the central city neighborhoods like the one I grew up in are asking the same questions I’ve been doing for years. When will we see the benefits?

The impact of the loss of over 91,000 manufacturing jobs in Milwaukee since 1963 cannot be downplayed. The recessions of 1974, 1980, 1981, 2001 and the Great Recession of 2008 have been felt particularly harshly in the central city by black and Latino residents. Many people blame the conditions in those communities on the residents without understanding the backstory of places like A.O. Smith.

It’s time we begin to open our eyes so that we can open our hearts and build empathy for these communities. More importantly, its time we put as much energy and financial resources into improving the employment situation for these forgotten sectors of Milwaukee.

As I look at the dozens of abandoned factories in the adjacent 30th Street corridor, I’m reminded of what someone said to me years ago about that neighborhood. “If they cared about us, our neighborhood would not look like this. Do they even care about us?”

© Photo

Milwaukee Public Library, UWM Libraries Digital Collections, Lee Matz, and Google Map