When the motion picture “The Outlaw Josey Wales” premiered in theaters across America in 1976, it was quickly embraced as a bold, revisionist Western that rejected the romantic simplicity of old Hollywood.

With Clint Eastwood directing and starring, the film delivered a gritty anti-hero narrative at a time when American audiences, still reeling from Vietnam and Watergate, were ready to question power and authority.

But beneath the dust and gunpowder, Josey Wales carried something else. It was a subtle but persistent narrative that aligned with the Lost Cause mythology of the American South.

The film follows a Missouri farmer-turned-bushwhacker after his family is murdered by Union irregulars. It was an adaptation of a 1972 novel written by Forrest Carter. The name would later be revealed to be a pseudonym for Asa Earl Carter, a former Ku Klux Klan leader and segregationist speechwriter for Alabama Governor George Wallace.

The novel, first published as “The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales” and later retitled “Gone to Texas,” helped launch Carter’s reinvention as a folksy, Cherokee-identifying storyteller. It was a fabricated identity that would begin to unravel after the success of Eastwood’s film adaptation.

At its surface, Josey Wales is not an overtly political film. It presents itself as a story of revenge and survival, about a man wounded by war, betrayed by his country, and forced to live outside the law.

But what makes Josey Wales so significant in the context of cultural memory is precisely what it omits and distorts. It is a film that reinforces the core tenets of the Lost Cause. Not through bombast, but through silence, character framing, and narrative sleight of hand.

The Lost Cause myth emerged in the aftermath of the American Civil War as a concerted effort to reframe the South’s humiliating defeat. Promoted by former Confederate traitors, racist Southern civic organizations, and sympathetic historians, the narrative portrayed the Confederacy as a noble cause. It was rebranded as a struggle rooted in states’ rights and personal honor, not slavery.

In this twisted telling of history, Confederate soldiers were patriots defending their homes from Northern aggression, while Union forces were oppressive conquerors. Over time, the myth became embedded in textbooks, public monuments, and popular media, especially through films like “Gone with the Wind” and “The Birth of a Nation.”

Josey Wales fits squarely within this tradition, though it arrived in a different cultural moment. Rather than being a romantic elegy to the Old South, it masked its sympathies in the grime and grit of a post-Vietnam Western.

Its Confederate protagonist is never seen fighting for slavery or secession. Instead, he is introduced as a grieving husband and father whose family is slaughtered by the Union-allied Redlegs. These soldiers are depicted in cartoonish fashion as sadistic, marauding killers.

This demonization of Union forces is not incidental. From the opening scenes, the Redlegs and their Union officers are portrayed as the film’s primary villains. Even after the war ends, the violence continues.

Former Confederate fighters who surrender are shown being executed under false pretenses, while Jose, having refused to surrender, becomes a hunted fugitive. The message is clear: the South, or at least those like Josey, fought an honorable fight and were betrayed by a vindictive victor.

At no point does the film address the central cause of the Civil War, which was slavery. There are no enslaved people in the narrative, no acknowledgment of the Confederacy’s defense of human bondage.

The war is presented purely as a personal and regional tragedy, devoid of its moral and political stakes. In doing so, Josey Wales replicates the most enduring feature of the Lost Cause, historical erasure.

Even as Josey moves westward and gathers a makeshift family that includes a Cherokee elder and a woman from Kаnsаs, the film’s redemption arc relies on the trope of reconciliation. It suggests that after the war, former enemies could come together to form something new, provided that the past was left unexamined.

This trope, familiar in many postwar narratives, frames the Southern fighter not as a traitor or oppressor, but as a misunderstood victim of history.

The film’s release during the U.S. Bicentennial gave it additional symbolic weight. Americans were reflecting on the nation’s founding ideals and the fragility of its institutions. In that climate, Josey Wales resonated with conservatives as a populist tale of individual resistance to corrupt power.

But it also provided a cultural safe haven for Confederate nostalgia, reframed not as White Supremacy, but as rugged independence.

Unlike older Lost Cause films that have faded from cultural relevance or been reevaluated for their explicit racism, “The Outlaw Josey Wales” remains a celebrated entry in American cinema. It is often cited among the greatest Westerns ever made, included in film syllabi and retrospectives, and hailed as one of Eastwood’s defining works.

Its mythic stature has allowed its ideological framing to go largely unchallenged. Yet its power lies in precisely that, its ability to smuggle Lost Cause ideology into a countercultural narrative.

Eastwood’s Josey is not a plantation owner or Confederate officer, but a working-class farmer drawn into the war through personal tragedy. This reframing allows audiences to identify with a Confederate guerrilla without ever confronting what that identity meant.

By divorcing Josey’s actions from any ideological context, the film converts a Confederate bushwhacker into a generalized American hero who distrusts authority, defends the weak, and rides alone.

In the process, the Confederacy becomes just a background setting, stripped of the trauma that represents its core meaning. This form of narrative laundering is not unique to Josey Wales, but the film executes it with rare effectiveness.

Much of this comes down to genre camouflage. As a Western, Josey Wales inherits a tradition of myth-making built on frontier violence, individualism, and the taming of wilderness. These stories often overlap with Civil War memory, especially when the protagonist is a former soldier headed west after the conflict.

In these narratives, moral complexity is replaced by cinematic shorthand. The gray uniform becomes a symbol of rugged masculinity, not political allegiance. The Old South is no longer a secessionist power defending slavery, but a stand-in for rural pride and anti-government rebellion. Viewers engage with the character’s suffering, not the historical cause.

That is precisely how Lost Cause tropes persist. Not always through direct assertion, but through strategic omission and emotional redirection. When Josey is wronged by Union forces, we feel sympathy. When he resists surrender and becomes an outlaw, we root for him. When he rides into a new life, we admire his resilience. None of this would be possible if the film engaged directly with what his cause truly represented.

And yet, the origins of that cause are embedded in the story’s DNA. Asa Earl Carter, writing under the name Forrest Carter, did not invent the Lost Cause, but he knew how to write in its voice.

His earlier life as a speechwriter for George Wallace, best known for the line “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever,” shows how deeply he understood the mechanics of racial grievance and historical manipulation.

His reinvention as a Cherokee storyteller was itself a kind of myth-making. He was a man who helped uphold White Supremacy, now recasting himself as a Native voice while simultaneously writing a book that romanticized a Confederate fighter.

Eastwood, to his credit, later expressed discomfort with some of Forrest Carter’s background and politics. In a 2008 interview, he said he had not known about Carter’s past when he took on the project. He viewed Josey Wales more as a story of personal loss and vengeance than political ideology. That distinction is important, but it does not mitigate the film’s cultural influence.

Stories shape memory, and memory shapes belief. “The Outlaw Josey Wales” may not have intended to propagate the Lost Cause, but it nevertheless participates in its cultural rehabilitation.

It gives modern American audiences a Confederate hero without making them wrestle with the Confederacy’s crimes. It invites empathy for a rebel while silencing the voices of those the rebellion subjugated. And it reinforces the idea that the South’s only sin was losing.

What makes Josey Wales so enduring, and so effective as a vehicle of myth, is that it does not feel like propaganda. It feels like a Western. Like a classic. Like America telling a story about itself. But within that story is a warped distortion of the truth that deserves to be named.

None of this requires the film to be “canceled” or banned. It remains an artful, compelling work that speaks to the anxieties of its time. What it does require is context and an understanding of how powerful stories can be, even when they leave things unsaid.

Josey Wales is not a relic of a bygone Hollywood. It is a reminder of how deep the Lost Cause runs, and how easily it hides in plain sight.

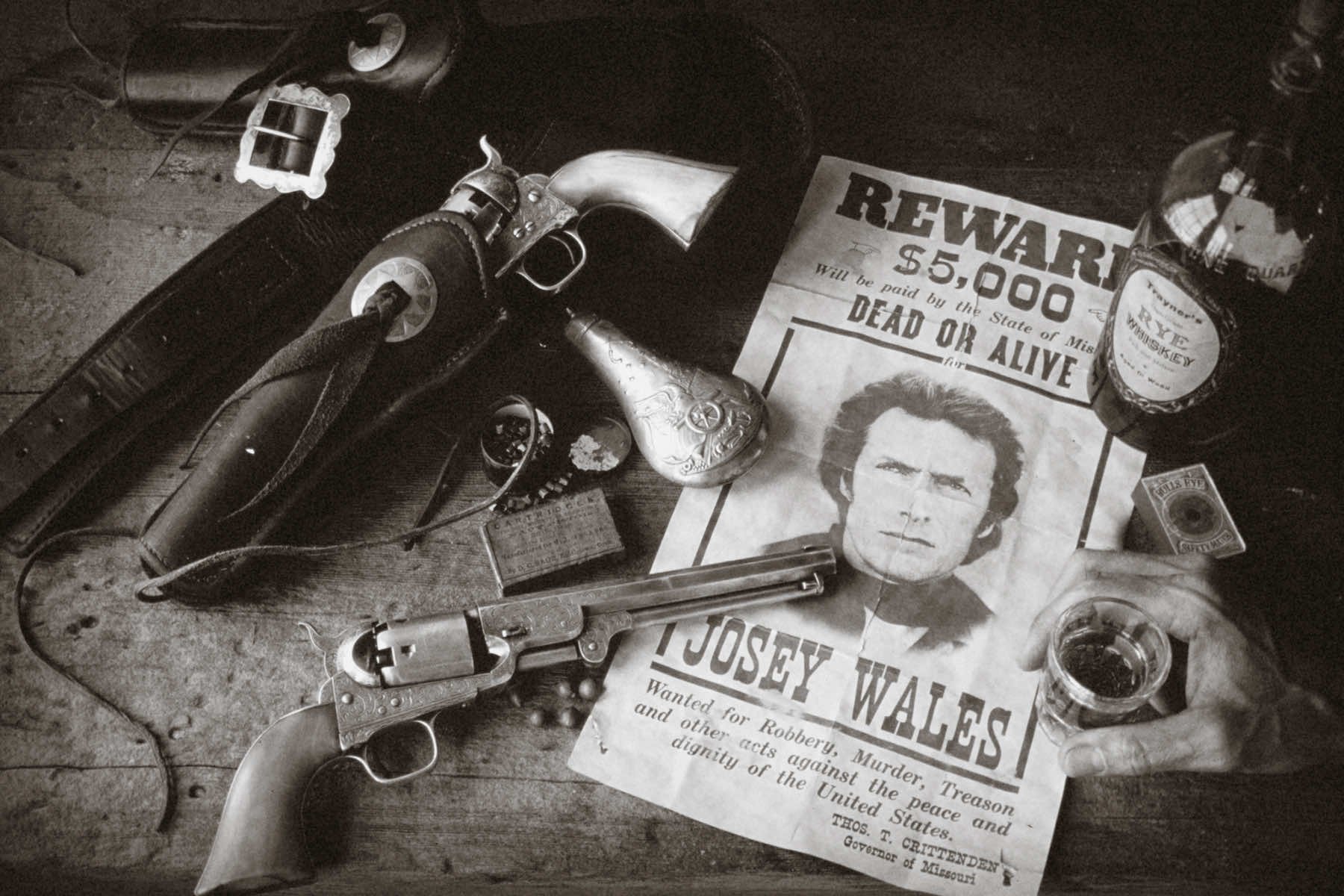

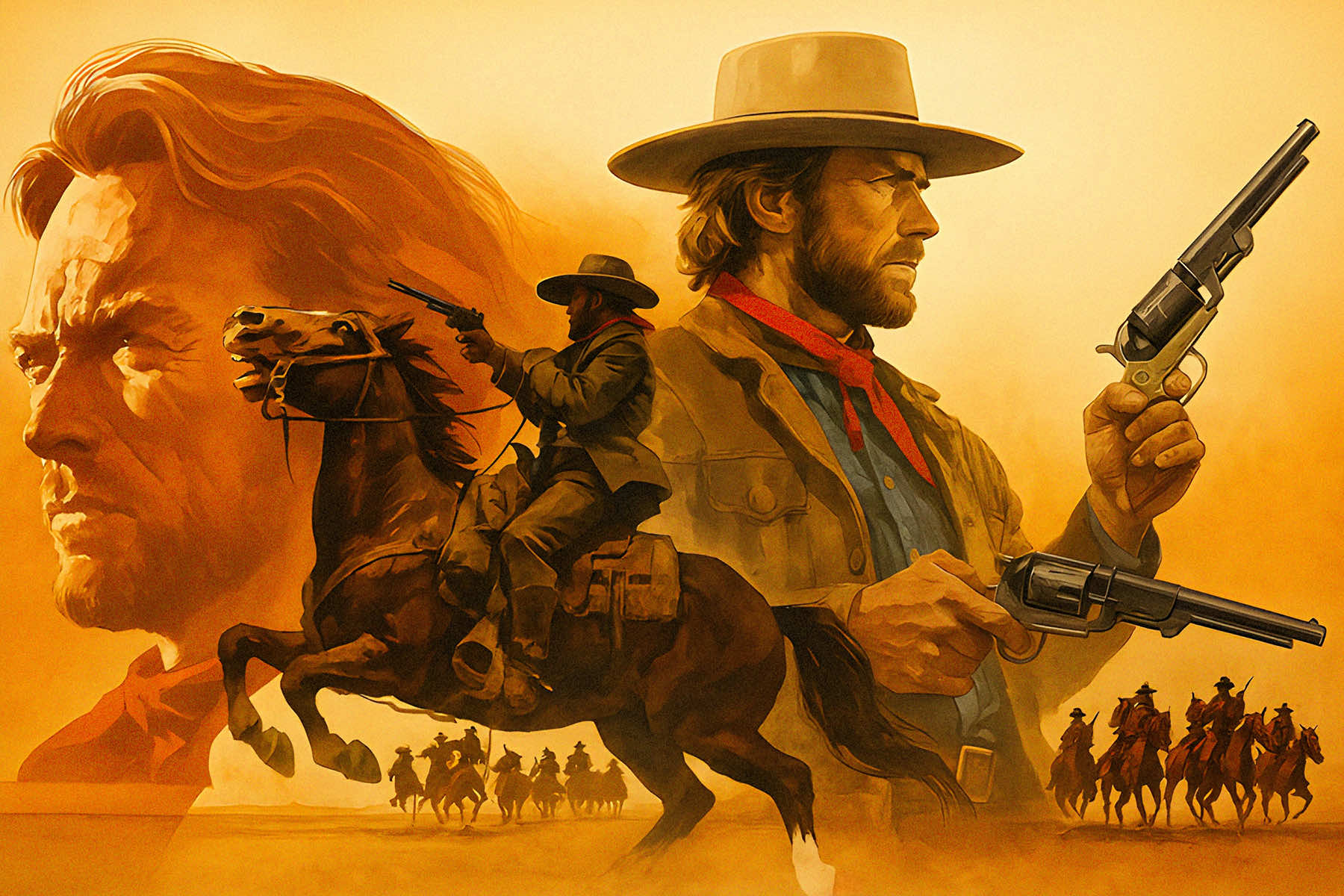

© Image

Illustration based on artwork from the Warner Bros. film “The Outlaw Josey Wales” (1976), produced by The Malpaso Company, and ZUMA Press (via Alamy Stock Photo)