It may seem odd at first that my monthly column exploring street photography, walking as a social practice, neglected public spaces, urban gardening and grassroots social justice takes a November pause to explore a play about two gay fathers in New York City. In some senses, though, I have been exploring Milwaukee’s family drama, how we live, work and play together, how we care for our “home” and those who live in it. How we succeed and how we struggle.

So, as the Trump administration tears apart immigrant families, tries to redefine and erase gender identities and continues to stir and legitimize anger and hatred, it can’t hurt to have a theatrical reminder (especially as we’ve just voted at the polls for midterm elections) of both how far we’ve come as a country and how we must not let the harmful paradigms of the past ruin the new normal of a connected future.

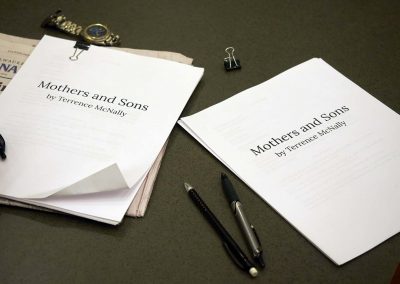

This month, the Boulevard Theatre is performing an enhanced reading of Terrence McNally’s 2013 groundbreaking drama Mothers and Sons, nominated for two Tony Awards, including Best Play, and also the first Broadway play to portray a legally wed gay couple on the stage.

The Boulevard has been exploring the LGBTQ experience for 32 seasons, with productions like Lillian Hellman’s disturbing The Children’s Hour, Evan Smith’s gay youth comedy Remedial English and an earlier portrait of gay parenting, Richard Kramer’s Theater District. It has “proudly maintained a safe space for theatrical exploration,” according to artistic director and founder Mark Bucher, “for artists of all sexual, sensual and romantic orientations, as well as all gender/transgender backgrounds.”

The Boulevard continues this tradition of LGBTQ-centric plays – as well as “a rich dowry of Milwaukee premieres, revivals of neglected literary gems and presentations of new works by local Wisconsin writers” – by opening its 33rd season with Mothers and Sons.

The enhanced reading – which means that actors will have memorized the script and interact with each other – will be performed at the LGBTQ-welcoming Plymouth Church on the Upper East Side, one of various locations which have been temporary homes to the Boulevard after leaving their Bay View storefront location four years ago.

Bucher is proud to be bringing this script to Milwaukee for the first time: “As an out gay man who lived through years of repression, discrimination, and personal violence, I attest that I seldom see non-musical productions that truly ‘celebrate’ the LGBTQ experience. Mothers and Sons truly celebrates that dynamic.”

The play is set entirely in the Central Park West apartment of husbands Cal and Will (15 years younger than Cal) and their six-year-old son Bud. As the play opens, we see that Cal has received an unexpected visitor: Katharine, the mother of Cal’s former lover. They stare out the window at a blustery winter park as Cal makes strained small talk, trying valiantly to deal with Katharine’s coldness and sarcasm (she keeps refusing his offer to take her coat).

The Boulevard Theatre cast will include Mark Neufang (“Cal”), Nathan Marinan (“Will”) and Joan End (“Katharine”). Neufang has performed in many plays written by gay playwrights or featuring gay characters, including Next Fall, Rope, The Normal Heart and McNally’s own Corpus Christi. He and his partner have been together for almost nine years. Marinan also performed in The Normal Heart, as well as Avenue Q, Jesus Christ Superstar and, most recently, Into the Woods.

He and his partner have been a couple for seven years and legally married for three. Director Bucher made sure to cast two gay actors to play the two gay characters. “There’s a sensitivity as gay men,” Neufang says, “that we can tap into that straight actors might not be able to.” Playing Katharine is End, well-known for her performances in Steel Magnolias, Little Gem, Rx, The Foreigner and Over the River & Through the Woods, and because this is a staged reading, all narration will be read by local actress, director and producer Pamela Stace, who remembers fondly her acting roles in Boulevard’s Three Hotels, Dear Liar, and Tartuffe.

This is not the first time the characters of Cal and Katharine have been on stage. In McNally’s Andre’s Mother (1988), a short three-page play that takes place at Andre’s memorial service, Katharine remained unnamed: simply “Andre’s mother.” At the end, she kisses a white balloon that Cal has told his friends represents the soul, then releases it into the air. Mothers and Sons reveals that even two decades later, Katharine has never truly let go of that balloon.

After Andre’s Mother, McNally would go on to spend the next two decades exploring the lives of gay men. In 1991, Lips Together, Teeth Apart portrayed two straight couples who gather at the summer house of one of the women’s brothers who has just died of AIDS. Others include the musical Kiss of the Spider Woman (1992), about a gay man and a revolutionary in an Argentinian prison; the Tony Winner for Best Play Love! Valour! Compassion! (1994) with eight gay men at all stages of life and imminent death; the play Corpus Christi (1997), which portrays Jesus and his disciples as gay; and the ambitious Some Men (2007) which explores eight decades of the gay male experience, including Stonewall, gay bathhouses, nightclubs and an AIDS hospital.

Then, in 2014, Mothers and Sons appeared on Broadway and for the first time portrayed two gay fathers and their son as a new normal. AIDS certainly took its toll on Katharine and Cal, but McNally never allows AIDS to take center stage in this play. It is part of a sad past of unruly death and discrimination that Will and Bud never had to experience and should never have to.

Instead, the normal life of Cal and Will and Bud is about going to work, making dinner, playing in the park, taking required baths, eating cookies, trimming Christmas trees. No didactic pomp and circumstance because, well, their life is normal. Katharine’s sudden arrival turns McNally’s play into a struggle, however, between the quotidian present and the painful past. “While society has changed a great deal,” McNally observed in a New York Times interview a month before Mothers and Sons opened on Broadway in 2014, “a lot of individuals like Katharine haven’t, and I wanted to show them as real, complicated people.”

We learn that her son Andre was Cal’s former lover, who died of AIDS twenty years ago, in 1994. Katharine has been unable to deal with Andre’s loss and carries under her winter coat two decades of pent-up grief, frustration, willed ignorance and anger. She is also a widow. However, on her way to Rome for Christmas Eve, she has decided to stop by to see Cal, whom she hasn’t talked to for two decades. Early on in the play, she remarks to Cal that it “gets so early this time of year… there’s no transition.”

Perhaps it is Katharine who is searching for some kind of transition, even subconsciously. Despite her scoffing at therapists in one scene, her sudden visit suggests her need for a catharsis she has not allowed herself for so long. Even the scene description at the beginning of the script (“the evolving warmth of the interior”) seems to foreshadow the play’s development, both in terms of the setting and the interior lives of the characters.

In between her coldness, sarcasm and presumptions, Katharine also asks a lot of questions about Cal and Andre, about Cal and Will, about Bud. She wrestles with Andre’s sexuality, who or what caused it and why he had to die so young. She not only wrestles with the constant specter of AIDS but with her own loneliness, with the lack of her own identity as anything but “Andre’s mother,” with how Cal and Will are raising Bud with no mother, with the normality of their lives while she has found herself with no family at all. She seems not only baffled and bitter but almost jealous of Cal – he had Andre, now he has a Will and also a Bud.

For me, her trip to Rome for Christmas Eve, with the convenient NYC stop, is her symbolic last-ditch effort to experience her own Nativity scene, with a new guiding star to some unknown salvation. She just doesn’t know yet how to seek the star and isn’t wholly ready for salvation.

But Will and Bud, according to McNally, represent that “whole new world” Katharine is seeking. McNally reflects: “I certainly know what Cal and Andre went through, and I’ve lived to see gay marriage and adoption and family. I wanted to look at how far we’ve come in society, so I don’t think of this as an update at all. It’s a new story. We can live a new story now.” While Katharine has closed her eyes to this journey, her perspective clouded and crowded by grief, perhaps by crossing the threshold into the apartment, she has taken the first step.

A few years ago, McNally reflected on why he wrote Mothers and Sons in a letter to Jane Unger, who directed the play at Portland’s Artists Repertory Theatre. “I sat down three years ago with a raging case of flu determined to write a play about what has happened to this country, but especially our LGBTQ community, in my lifetime… If you think Andre is me in tonight’s play, you’re right. Along the way, I found love often enough but I lost the love of my family as well and we became strangers.

It was both our loss. Since those many years ago I have made my own family for myself and by now we are generations deep in happiness and sadness and fulfilling relationships. The only people missing in my life are my parents. My husband’s father was his best friend. How I envy him that. I was not with my father when he died. When my mother died I was working on a show in Chicago. All I can do is live with her inability to love me as I truly am and try to remember the way she was and maybe even begin to understand us both a little. I adored her, you see. She was my mother.”

For ten years after I moved from Seattle to Milwaukee to attend graduate school, I, too, became estranged from my family. While my mother always told me she loved me, she also always told me that I would burn in hell if I did not abandon my “sinful habit,” being gay.

I came out to my parents after living in Milwaukee for about six months. Early on during our ten-year one-upmanship, which took the form of scores of letters back and forth, I met my partner, then his own family, all of whom accepted me with open arms. That was in 1995.

I started teaching college, then high school. I continued to write her, debate her, grieve with her about our disintegrating relationship and the seeming impossibility of reconciliation. After ten years, the record kept skipping and we both gave up. My mother, and my father by default, disowned me. I chose to continue living my life with my new family.

Finally, after two decades of living together as a couple, my partner and I got married in December 2016. It was lovely, of course, a small affair with my sister (now the only blood relative with whom I’m in contact), my husband’s family and some neighbors and friends. Our good friend performed the ceremony. But it was also a formality (we’d been partners, like I said, for twenty years), a legal move (same-sex marriage had finally been declared legal in all fifty states in 2015) and a political safeguard (we had no idea what Trump and Pence would try to do to undermine LGBTQ rights in the next four years). In any case, we continue living our lives like any normal couple. We consolidated some assets, I got health insurance again, we are planning our retirement together, and so on.

McNally reminds us that “AIDS is not the only scourge that decimated generations of gay men and women. The wounds of homophobia are still raw, deadly and tearing families apart… Cal is a survivor of our darkest years but if this play has a hero, it’s Will. If it has a future, it’s Bud. There are no villains, only a mother decimated by her inability to enter a new world, a world born of the tragedy of AIDS and now vibrant with new freedoms and infinite possibilities. God bless Katharine, too. She was Andre’s mother.” And God bless my mother, too, who has missed out on half of my life.

Indeed, things have changed a great deal and there are “new freedoms and infinite possibilities.” So much has been normalized, so much assimilation has occurred. Very little seems to shock most people anymore. The need for LGBTQ theater, then, has been questioned for many years. Of course, plays will still be written by and for LGBTQ individuals, but do we even need to differentiate or label anymore? Do we need LGBTQ-run or focused theaters in a post-Stonewall, post-AIDS era in which same-sex marriage is legal? Is there any need for LGBTQ bars or clubs anymore? If everyone’s equal, then is there still a need for exclusive or safe spaces? Do LGBTQ people have anything to fight for or against anymore?

The fact is that “Katharines” still exist and must be argued against. We all know that transphobia and homophobia still exist, even sadly (and sometimes shamefully) within the LGBTQ community itself. LGBTQ youth suicide rates are still significantly higher than others of the same ages. Twenty years after the murder of Matthew Shepard, Wyoming is still one of five states with no hate crime laws; fifteen states don’t punish based on a victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity.

And we need no reminding of the Trump administration’s move earlier this year to ban transgender citizens from serving in the military or the more recent move to define gender based on genitalia at birth, a definition that would “erase” the identities of over 1 million Americans who identify as transgender. The latest draft of the 2020 census has removed proposed questions about sexual orientation and gender identity. To answer the last question above: Hell yes, the fight goes on.

The list of “Katharines” goes on and on, but unlike McNally’s empathy for his Katharine’s loss, his ability to give her voice and space where she has denied it for long, these very real “Katharines” don’t need understanding – they need to be defeated. And it’s going to take something more than a play to combat them.

For sure, as I say at the beginning, we need Mothers and Sons now, and the Boulevard cast will deliver a compelling reading of a hopeful play. And I will be in the audience with my husband as we live our normal lives. But after the play, I will need to start thinking about how I’m going to be more disruptive and political, more queer – because the lives of “Andres” and “Cals” and “Wills” and “Buds” depend on it.

Mothers and Sons runs November 15, 18, 19, 23, 24, and 25 at Plymouth Church’s Graham Chapel, 2717 E. Hampshire Avenue. Check brownpapertickets.com/event/3819435 for exact times and details and to purchase tickets.

© Photo

Troy Freund