On May 4, 1905, a British freighter named Ilford arrived at the port of Salina Cruz, carrying 1,033 Korean passengers bound for agricultural labor in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula. Most of them had never heard of Mexico. Few of the men, women, and children knew what work awaited. But all had been recruited under promises of land, wages, and opportunity.

The reality that met them in Yucatán’s henequen plantations was far from those assurances. What was meant to be a short-term overseas contract transformed into a permanent and often punishing displacement, forged by geopolitical manipulation, imperial subjugation, and a system of forced labor that operated under conditions of captivity and coercion.

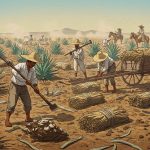

Known among themselves as Aenikkaengs (애니깽), a Korean transliteration of “henequén,” the crop they were contracted to harvest, the migrants quickly became defined by their work. That name, born from necessity and exile, reflected how deeply their lives were shaped by the forced labor camps of the Yucatán.

On this 120th anniversary of their arrival, descendants and historians alike are working to reclaim a story that challenges the old narratives of the Korean diaspora and exposes the colonial systems that shaped global migration.

THE JOURNEY FROM INCHEON TO YUCATÁN

The mass migration of Koreans outside of Asia had only begun in 1902, when laborers were recruited to work on sugar plantations in Hawaii. By 1905, Japanese imperial interests sought to restrict Korean migration to Hawaii, fearing it would undercut Japanese laborers and fuel anti-Japanese sentiment in California.

To divert Korean emigration away from American territories, Japanese authorities and private emigration firms encouraged an alternate destination: Mexico.

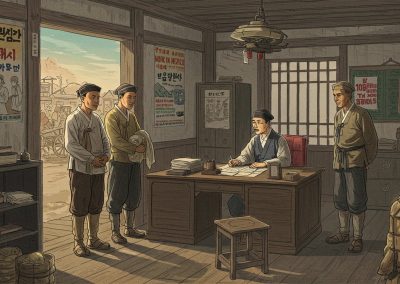

Recruitment for this project was led by the Continental Migration Company (大陸殖民合資會社), a Japanese firm founded in 1903. Its president, Hinata Terutake, and a company agent based in Seoul, Oba Kannichi, began coordinating with a British labor recruiter, John (Juan) C. Meyers, in 904 to send Korean workers to Yucatán.

The recruitment campaign, published in newspapers like Daehan Ilbo and Hwangseong Shinmun, advertised Mexico as a paradise. Farmers were promised free transport, housing, land for cultivation, health care, education for children, and return passage home, along with a 100 peso bonus upon completion of their contract.

These advertisements misrepresented the true nature of the work. The Koreans were, in fact, entering the henequen (Agave fourcroydes) economy, a monoculture plantation system whose labor force, largely composed of indigenous Maya and forcibly deported Yaquis, endured de facto slavery.

Mortality among laborers exceeded birth rates, and debt peonage, known locally as enganche, legally bound workers to hacienda owners through advance loans they could rarely repay. A 1911 observer noted that two-thirds of the indigenous laborers brought to Yucatán died within their first year.

Once the Continental Migration Company began securing workers, passport legality posed another complication. At the time, all legal overseas migration of Koreans was under the exclusive authority of American entrepreneur David W. Deshler, who had secured royal approval in 1902.

The Ilford passengers did not have Korean government passports. Meyers, blocked from obtaining British documents, sought the help of the French legation in Seoul. French diplomat Victor Collin de Plancy ultimately authorized travel papers for the group, allowing their departure from Incheon in April 1905.

A COLONIAL MIGRATION WITHOUT DIPLOMATIC TIES

What made this migration unique was the absence of direct diplomatic or colonial ties between Korea and Mexico. The Korean Empire was already under Japanese surveillance, but formal annexation by Japan would not occur until 1910.

Meanwhile, Mexico had no prior diplomatic relationship with Korea, nor any history of receiving Korean labor. The transpacific labor link between Incheon and Yucatán was made possible not by bilateral agreement but by intersecting imperial strategies.

These forces included Japan’s attempt to control Korean mobility, Mexico’s labor shortage under Porfirio Díaz’s regime, and global market demands for henequen rope used in shipping.

The Korean laborers moved between two colonial systems. One was formalized through Japan’s encroaching annexation of Korea, and the other was expressed through the plantation-style colonial system hacienda system in Mexico.

The Korean migrants were subject to imperial and settlement-based colonization forces, even though they were not moving between a colony and an empire. Their migration defied the usual divide between colonizer and colonized nations, placing their experiences outside the traditional accounts of mainstream migration narratives.

LOST IN THE HACIENDA SYSTEM

The original labor contracts were fixed at four to five years. Many of the workers arrived expecting to return home with savings. But with Korea’s diplomatic sovereignty stripped following the Eulsa Treaty in November 1905, the possibility of return collapsed.

Within months of the Ilford’s landing, Japan’s annexation of Korea began in earnest. Korean institutions abroad lost consular protection, and migrants were effectively stranded without a state.

The start of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 further destabilized their situation. Henequen production declined, violence spread, and the plantation system that had first bound them began to unravel. But by then, many had already settled into new patterns of survival.

For the early Korean settlers and their children, cultural preservation was not just difficult, it was nearly impossible. Scattered across the Yucatán Peninsula’s henequen plantations, families lived in geographic isolation, often on estates dozens of miles apart. There were no Korean-language schools, newspapers, or churches.

Intermarriage with local Maya and mestizo populations increased. Cultural adaptation occurred under constraint, not celebration. Many Koreans changed their names, adapted to Catholic traditions, and blended into Mexican society in order to survive.

Spanish and Mayan were the languages of education and labor, while Catholicism dominated social life. Conversion was common, sometimes voluntary, sometimes imposed, and with it came new names, new customs, and a slow departure from ancestral practices. Korean holidays went unobserved. Ancestor rites were forgotten.

Children born from these unions often spoke only Spanish or Yucatec Maya, and Korean identity faded into silence over generations. Despite the cultural disconnection that followed, threads of Korean heritage persisted in families through heirlooms and oral memories.

Some descendants remembered elders who kept faded portraits of Korean ancestors or passed down story fragments about a long sea voyage, broken promises, and wages that never came. In certain households, Korean surnames endured, passed down through descendants even when little else of the language or custom remained.

A MEMORY LOST BUT A HERITAGE REDISCOVERED

It was not until the latter half of the 20th century that the Korean Mexican community began to receive external attention. South Korean diplomats, researchers, and journalists started visiting Yucatán in the 1970s to locate descendants of the original migrants.

Their interest coincided with a period of diplomatic normalization between South Korea and Latin American nations, and the rediscovery of the Ilford passengers served both historical and symbolic purposes.

A 2005 centennial celebration, supported by the South Korean government, included the dedication of a monument in Mérida’s city center, inscribed with the names of the original laborers. Yet recognition did not translate into full reintegration.

Many descendants interviewed during centennial commemorations reported feeling culturally Korean only in the abstract. They were, in practice, entirely Mexican. Their lives had been shaped by Maya heritage, Catholic festivals, and local customs.

What connected them to Korea was not language or ritual. It was a historic rupture that began with deception, endured through survival, and ended in cultural transformation. Yet, some younger generations have made efforts to reconnect with their heritage.

In recent years, local associations like the Asociación Coreano-Mexicana have organized language classes, genealogy projects, and educational programs to bridge the cultural gap. South Korea has extended invitations to some descendants for heritage tours and cultural exchanges. A few have even relocated to Seoul or Incheon in search of identity, jobs, or historical roots.

But such journeys are often bittersweet. The migrants of 1905 left Korea before the country was colonized, divided, or industrialized. Descendants returned to a nation that had no resemblance to the one left behind.

Their story also complicates the dominant Korean narratives about overseas migration. Most modern accounts focus on successful businesspeople or cultural ambassadors. These were Koreans who voluntarily emigrated to the United States, Canada, or Australia in the late 20th century.

By contrast, the Ilford migrants were recruited under false pretenses, subjected to debt servitude, and left to adapt without institutional support. Their story, long excluded from South Korea’s national memory, raised questions about which migrations get honored and which are left forgotten.

A HISTORY FORGOTTEN BY TWO NATIONS

Mexico, too, has yet to fully integrate the Korean labor story into its national history. Unlike the well-known accounts of Chinese railroad workers or Japanese farmers in Baja California, the Korean indenture in Yucatán is rarely taught in schools or marked by civic holidays.

Those Korean settlers arrived not as part of a migration wave meant to build the nation, but as disposable labor for an economy built entirely around a single crop. Their assimilation into rural communities was gradual, often invisible, and shaped by the same racial and class hierarchies that governed indigenous laborers.

Still, their presence endures 120 years later. In villages across Yucatán and Campeche, Korean surnames appear on electoral rolls. In some households, old photographs and oral tales continue to circulate.

And every May 4, a small group gathers in Mérida to read the names carved into the granite monument, names once omitted from the histories of two nations, now reclaimed as part of both.

This anniversary is not just about remembering a voyage in 1905. It is about recognizing a community forged by abandonment and endurance, deception and survival.

It is about placing Korean Mexicans not at the margins of either country’s narrative, but within the overlapping histories of empire, migration, and cultural reinvention.

For the descendants of those first 1,033 travelers, that recognition is long overdue.

Correo Del Maestro, Inri (via Wikipedia), and Guillermo G. (via Shutterstock)

Isaac Trevik

This article draws on historical research and analysis from Michelle Ha’s “Decolonizing Migration Theory: Korean Indentured Labor Migration to Mexico as Case Study” and Hea-Jin Park’s “Dijeron que iba a levantar el dinero con la pala: A Brief Account of Early Korean Emigration to Mexico.”