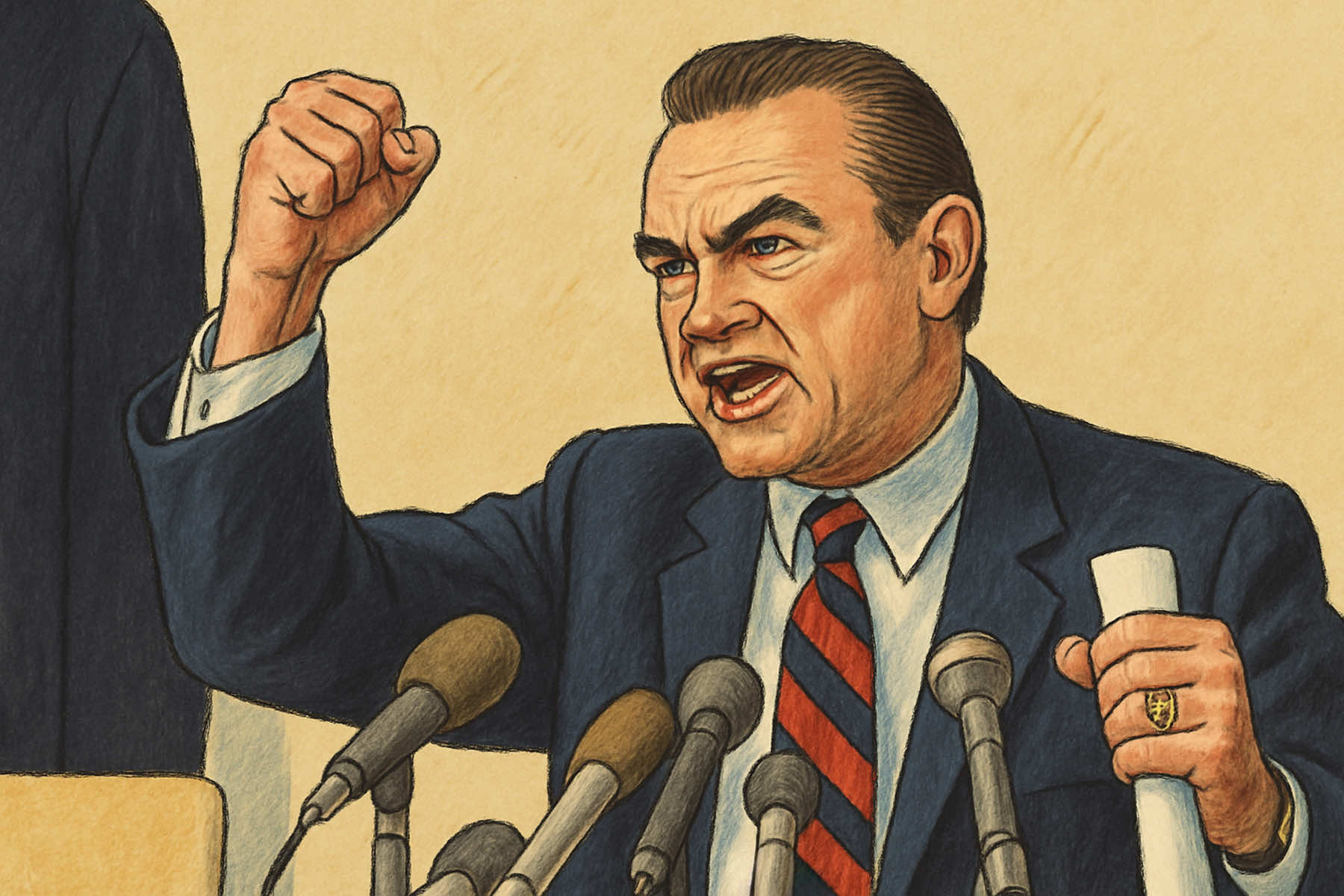

In April 1964, Alabama Governor George Wallace entered the Wisconsin Democratic presidential primary as a defiant challenger to the mainstream liberal consensus.

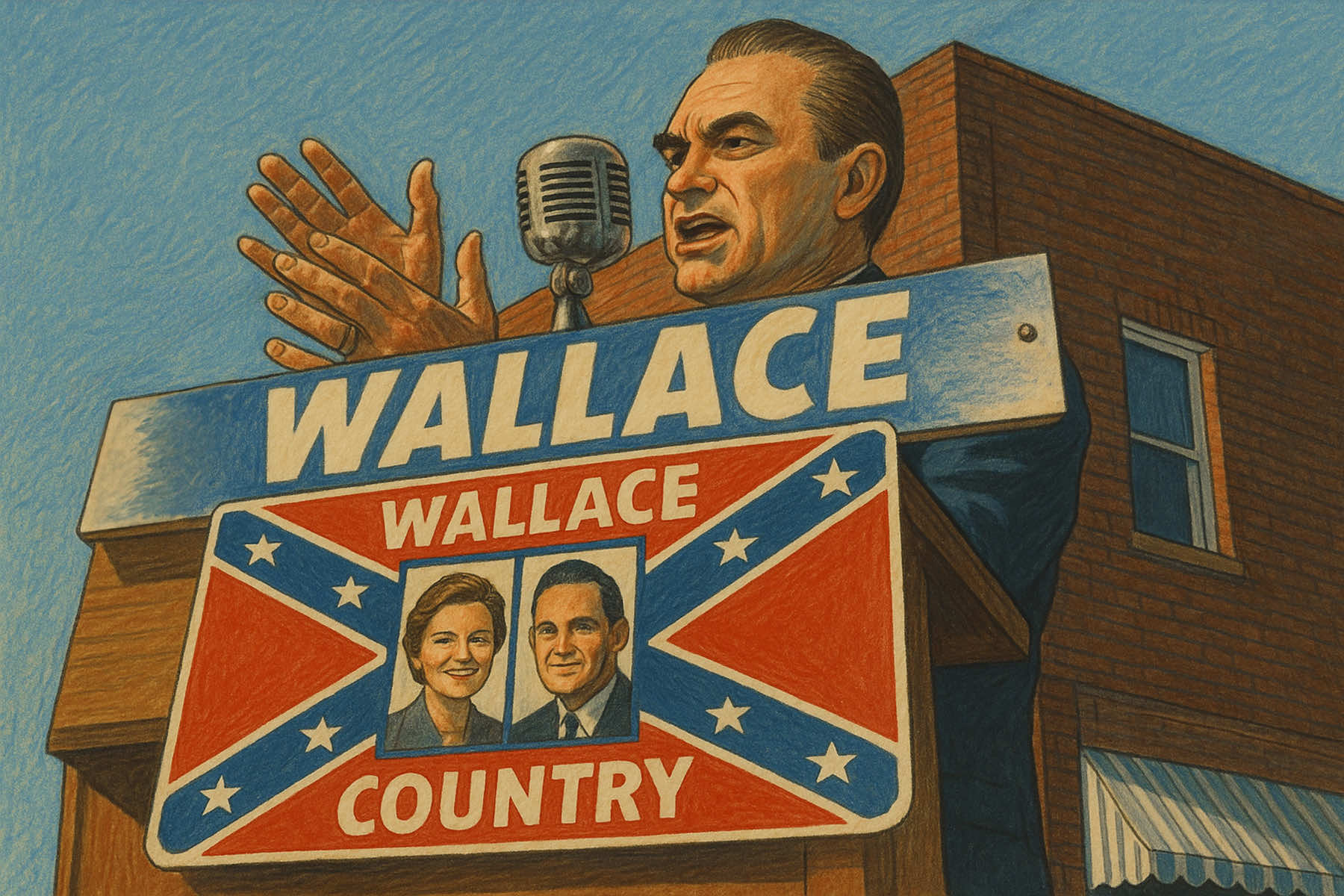

Known nationally for his opposition to desegregation and federal civil rights mandates, Wallace used Wisconsin as a political laboratory to test whether his hardline message, rooted in states’ rights, anti-federalism, and White backlash, could resonate outside the South.

His surprising success shocked the national Democratic Party and exposed emerging cracks in the New Deal coalition.

Wallace’s decision to campaign in Wisconsin appeared quixotic at first. He had no local organization, no endorsements, and faced an electorate far removed from the Jim Crow South. But Wallace believed that discontent with civil rights legislation and growing distrust of Washington’s social engineering could be found even in northern union towns and farm counties.

He framed his campaign around themes of “law and order,” local control, and opposition to what he called federal overreach, avoiding overt racial rhetoric while leaving little doubt about its implications.

Despite being labeled a protest candidate, Wallace invested serious effort into the Wisconsin primary. He fielded an ad hoc network of conservative activists, local volunteers, and sympathetic blue-collar voters who were angry over civil rights, school integration, and perceived liberal elitism.

His message was deliberately stripped of Southern inflection. Instead, it appealed to northern concerns about taxes, crime, and social change.

Wallace’s support was strongest in working-class areas undergoing demographic transition. In counties like Racine, Kenosha, and parts of Milwaukee, White ethnic communities faced pressure from housing integration and changes in public education.

In small towns and rural districts, farmers and independent voters expressed anxiety over shifting cultural norms and federal agricultural policies. Wallace tapped into these frustrations with calculated bluntness.

He campaigned aggressively across the state, holding town hall meetings, speaking on the radio, and hammering at themes that painted Washington as distant, arrogant, and indifferent to everyday people. He accused the federal government of ignoring the rights of states and undermining the authority of local communities.

While he refrained from explicitly racist statements, his warnings about “forced integration” and “social experiments” were clear in their meaning.

The Wisconsin primary was held on April 7, 1964. Wallace captured more than a third of the Democratic vote statewide, winning over 40 percent in some industrial counties. In heavily unionized neighborhoods, he outperformed expectations, drawing support from voters who had once backed liberal candidates but now felt alienated by the party’s civil rights platform.

Wallace’s message resonated especially in precincts where White working-class voters believed their interests were being sacrificed for minority advancement.

Though President Lyndon B. Johnson remained the dominant figure in the race and ultimately carried Wisconsin, the Wallace vote sent shockwaves through both political parties. The results demonstrated that racial resentment and conservative populism could gain traction even in northern states traditionally aligned with liberal policies.

For party leaders and political strategists, the Wisconsin results forced a reckoning: the New Deal coalition was beginning to fracture under the weight of civil rights reform and cultural change.

The 1964 campaign in Wisconsin foreshadowed a national shift. Wallace revealed that a segment of the electorate, particularly White, working-class voters, was open to a message of backlash against rapid social transformation.

While he framed his campaign around constitutional principles and individual freedom, the emotional core of his appeal lay in a deep resistance to the racial and cultural upheavals of the era.

Wisconsin, often seen as a bastion of progressivism, exposed its own vulnerabilities. Many voters who supported liberal economic policies were not fully aligned with the Democratic Party’s growing emphasis on racial justice.

Wallace’s campaign exploited that gap, appealing to union members, small business owners, and rural conservatives who felt disconnected from the party’s direction.

The results also highlighted the limits of traditional party loyalty. Voters who had long identified as Democrats were now willing to cross ideological lines when they felt their core values were threatened. This erosion of partisan discipline would have lasting consequences, opening the door for future candidates to build cross-party coalitions based on cultural and racial identity.

In hindsight, Wallace’s performance in Wisconsin marked more than a momentary protest. It signaled the emergence of a new political vocabulary, one that would be refined and redeployed by politicians in both parties over the next five decades.

The campaign served as a test case for how far themes of resentment, cultural anxiety, and opposition to federal authority could travel. In 1964, they traveled farther than most observers expected.

The lessons of Wallace’s 1964 campaign in Wisconsin are not confined to the past. The political conditions that allowed a segregationist governor from Alabama to earn over a third of the vote in a northern Democratic primary did not disappear with the end of the civil rights era.

Instead, they evolved into a broader phenomenon: the alignment of White working-class voters with conservative cultural politics, often in opposition to the liberal policies they once supported economically.

In the decades following Wallace’s campaign, national political figures adopted elements of his message while discarding its more overt racial baggage. Richard Nixon’s “Southern Strategy,” Ronald Reagan’s appeals to the “silent majority,” and even Democratic triangulation in the 1990s drew from the same well of disaffection Wallace had tapped in Wisconsin.

Economic insecurity, cultural change, and distrust of federal authority remained powerful motivators for a sizable portion of the electorate.

Wisconsin would again play a leading role in illustrating these dynamics. In 2010, the election of Scott Walker as governor, fueled by a backlash against public unions and framed in terms of taxpayer fairness, echoed Wallace’s earlier appeals to resentment against perceived liberal overreach.

In 2016, Donald Trump’s success in the state further underscored how White, non-college-educated voters, many of them former Democrats, could be mobilized through messages focused on nationalism, identity, and economic grievance.

The shift in political identity among Wisconsin’s White working class transformed the state’s electoral map. Counties that once anchored Democratic victories with strong union turnout and liberal social policies have become battlegrounds or flipped entirely.

These changes did not happen overnight, and they were not inevitable. But the roots of this transformation can be traced to moments like Wallace’s 1964 campaign, when traditional political loyalties were first disrupted by cultural backlash.

Then, as now, candidates often frame civil rights, immigration, and social equity policies as zero-sum threats to the perceived cultural or economic standing of the majority population.

Then, as now, issues of race, class, and identity converge in ways that transcend simple partisan labels. What Wallace revealed in Wisconsin was not a one-time fluke, but a reordering of political dynamics based on emotion, status, and cultural anxiety.

For political strategists and historians alike, the key takeaway from Wallace’s campaign is the importance of recognizing when identity politics eclipses traditional policy debates. Wallace did not offer detailed economic plans or foreign policy proposals. He offered a sense of defiance, an emotional connection to voters who felt mocked, displaced, or ignored.

That strategy remains effective today, especially in regions undergoing demographic or economic transition. Another lesson lies in the failure of party institutions to anticipate or blunt Wallace’s appeal.

National Democrats in 1964 assumed that civil rights legislation would only provoke Southern resistance. They were unprepared for how the same rhetoric could resonate in union halls, farming communities, and small cities across the North. That miscalculation cost them not only votes in a primary, but long-term loyalty from segments of their base.

Contemporary politics continues to grapple with similar blind spots. Whether it is voter reaction to immigration policy, criminal justice reform, or gender and education debates, party leaders often misread how these issues are felt and discussed outside of urban centers.

Wallace’s campaign suggests that political messaging cannot be crafted solely for elite audiences or activist coalitions. It must also contend with the fears, resentments, and aspirations of people who believe their world is changing without their consent.

Wisconsin remains a bellwether for this tension. Its voters have swung between progressive and conservative candidates, often within the same election cycle. This volatility is not random, it reflects a population still divided between its progressive traditions and its susceptibility to populist appeals grounded in cultural preservation.

For every breakthrough in racial or social justice, there remains a countercurrent ready to resist, often with deep historical precedent.

Wallace did not win the presidency. But in Wisconsin, he won something arguably more consequential: proof that a politics of grievance could mobilize White voters outside the South.

His campaign offered a preview of the national coalitions that would reshape American politics for decades. Understanding that moment is essential not only for explaining how Americans voted for a second Trump presidency, but for imagining where the politics of identity, backlash, and belonging may go next.

© Art

Isaac Trevik (based on historical photos via AP)