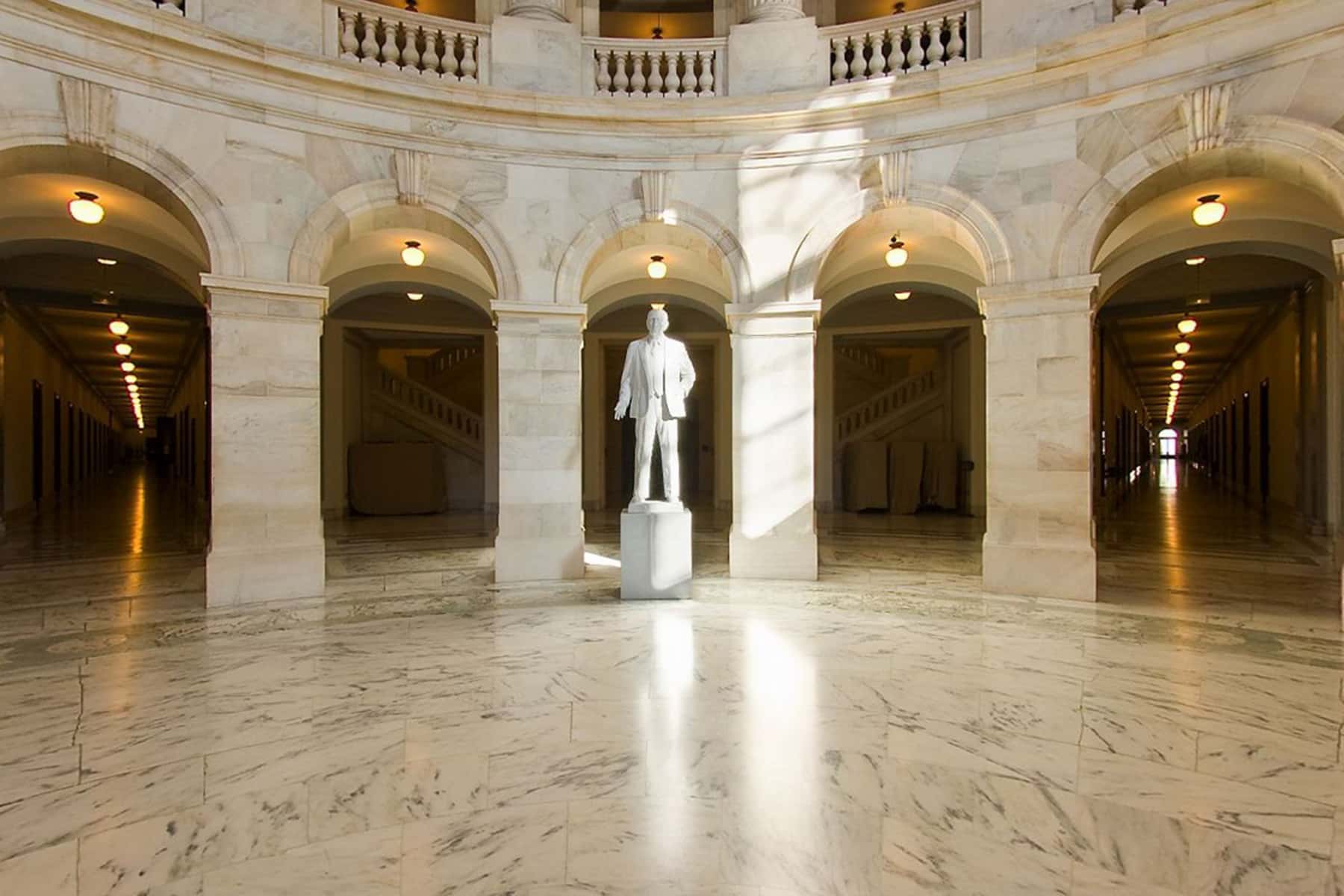

It is time to rename the Russell Senate Office Building, where 33 senators today conduct their daily business, and the effort would be more than a symbolic gesture.

Senator Richard Russell was most famous as the guy who wielded the filibuster to destroy Civil Rights legislation. Most of the time he was quite successful, spending decades scuttling legislation proposed to outlaw lynching, end school segregation, or to insure voting rights.

In 1932 Russell, then the openly segregationist Governor of Georgia, won election to the U.S. Senate from that state, taking office in 1933. He immediately joined the “Southern Bloc” to fight northern Democrats Robert Wagner’s and Edward Costigan’s proposed 1933 legislation to outlaw lynching.

First lady Eleanor Roosevelt had joined the NAACP by then and was an outspoken advocate of the anti-lynching legislation, which so pissed off Southern Democrats like Russell that they threatened to block parts of President Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation if he signed onto the bill.

Their efforts notwithstanding, the anti-lynching legislation championed by Eleanor Roosevelt and Robert Wagner made it through the House: it landed in the Senate with a thud.

Richard Russell immediately stepped up to kill the bill, establishing a pattern of opposing Civil Rights legislation that held for his entire political career.

“As one who was born and reared in the atmosphere of the old South,” Russell said when the legislation was brought forward, “with six generations of my forebears now resting beneath Southern soil, I am willing to go as far and make as great a sacrifice to preserve and insure white supremacy in the social, economic, and political life of our state as any man who lives within her borders.”

That man — who proudly and eloquently proclaimed he was willing to lay down his life to defend white supremacy — is now memorialized daily, every time somebody notices or mentions his name in the context of the oldest and most storied of the Senate’s three office buildings.

Russell was so passionate about maintaining the right of white people to hang Black people by the neck for public spectacle that he personally filibustered Senator Wagner’s and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s 1935 anti-lynching bill for six long, exhausting days. It established him, along with Senator Strom Thurmond, as one of the Senate’s leading defenders of white supremacy.

Three years later, when Senator Wagner got a new anti-lynching bill through the House and to the Senate in 1938, Russell participated in a successful thirty-day filibuster of the legislation.

In the 1940s, after FDR died and President Harry Truman proposed civil rights and anti-lynching legislation, Russell was at the tip of the spear using the filibuster against his own president every time, much like Manchin and Sinema are today.

By the 1950s, Russell was an old hand at using the filibuster to block civil rights legislation, which had been the filibuster’s main use since the end of the Civil War.

Every two years through the entire decade of the 50s, Hubert Humphrey and his liberal colleagues re-introduced legislation to outlaw lynching, racial discrimination in hiring, or poll taxes and other voter suppression techniques then in widespread use across the South.

And every time, Richard Russell led or co-led the opposition. As Humphrey biographer James Traub wrote last year:

“As soon as a motion to consider the [civil rights] measures was proposed, Russell would spring into action like Napoleon dispatching his marshals to the enemy’s flanks. He would typically organize four two-man teams, each assigned to monopolize a four-hour block of debate. His men could keep up this regimen for weeks if need be. As soon as Russell saw exhausted opponents leaving the chamber, he would call for a quorum. If fewer than half the members — then 48 — remained, the house would adjourn, thus wasting another day and driving the other side further to despair.”

Blocking civil rights was the passion of Richard Russell’s entire career, from the Georgia House to the Georgia Governor’s mansion to the United States’ Senate.

As the U.S. Senate’s “archived senate floor proceedings” site notes, when President Lyndon Johnson’s allies brought the Civil Rights Act to the floor of the Senate in the spring of 1964:

“Senator Richard Russell of Georgia pledged that he and his colleagues in the southern bloc would fight the bill to the bitter end. ‘Despite overwhelming odds,’ he proclaimed, ‘those of us who are opposed to the bill are neither frightened nor dismayed.’ The bill’s opponents, Russell declared, would wage a ‘good fight for constitutional government.’”

Senator Hubert Humphrey was having nothing of the “constitutional government” manure that Russell and his racist buddies were flinging.

“It is difficult,” Humphrey said on the floor of the Senate, “to fully comprehend the monstrous humiliations and inconveniences that racial discrimination imposes on our Negro fellow citizens.”

The Senate archive noted:

“[Humphrey] presented as examples two travel guidebooks written for family vacation planners. One identified hotels that allowed pets to stay overnight. The second book listed hotels that allowed black guests. ‘In Columbus, Georgia,’ Humphrey explained, ‘there are six places for dogs and none for Negroes.’ In Charleston, South Carolina, ‘there are 10 places where a dog can stay, and none for a Negro.’”

In response, Russell stood up to warn his colleagues that the Civil Rights Act “would permit Negroes to get into any private club in the nation.” As the Senate archives document:

“Senator Richard Russell cautioned that H.R. 7152 would break down the South’s ‘two different social orders’ — one white, one black — leading to the ‘amalgamation and mongrelization of our people.’”

Russell was furious when Vice President Humphrey imitated his own tactics, deploying teams of senators Humphrey called “Civil Rights Corporals’ Guard” to stay on the floor in rotating blocks to break the filibuster: it worked and the Civil Rights Act passed.

Russell expressed his anger by very publicly refusing to attend the DNC’s presidential nominating convention that year in Atlantic City, an open slap at his own party’s president, who proudly signed the legislation. By the 1970s segregationists were still a major force in politics, particularly in the South.

In the 1970 election that brought George Wallace back into the Georgia Governor’s Mansion once occupied by Russell, for example, Wallace ran ads featuring a pretty little white girl surrounded by seven menacing-looking Black young men bannered with the slogan: “Wake Up Alabama! Blacks vow to take over!”

Thus, when Russell died in 1972, the segregationists sprang to action to create one more memorial to racism in America. Within weeks of his death, they had pushed through Congress a resolution to affix his name to what is now the Russell Senate Office Building.

This history of Russell’s masterful work using the filibuster to promote white supremacy and block civil rights and anti-lynching legislation — now carried on by the entire Republican caucus and Democratic Senators Manchin and Sinema — is not a secret in the halls of Congress.

In June of 2020, House Resolution 1042, “Calling on the Senate to rename the Russell Senate Office Building,” was introduced by Representatives Green, Bass, Castor, Cleaver, Cooper, Garcia, Haaland, Hastings, Kennedy, Lawson, Lee, Lowenthal and Thompson.

It is not only good policy, it is also good politics. If done right, the debate around this, and the public proposals for alternate names, could highlight this issue of fifty-two senators “protecting the filibuster” while refusing to protect voting rights for all Americans. It is time to re-introduce it as a way of reminding our senators of the despicable history of those who use the filibuster to block civil and voting rights legislation.

Chіp Sоmоdеvіllа and J. Scоtt Аpplеwhіtе

© Thom Hartmann, used with permission. Originally published on The Hartmann Report as Want to ‘Highlight’ Senators Blocking Voting Rights? Rename the Russell Senate Office Building!

Subscribe to The Hartmann Report directly and read the latest views about U.S politics and other fascinating subjects seven days a week.