The decade since has seen a rise in mass shootings and terror attacks on places of worship. Sikhs hope the anniversary helps reverse those trends.

In India, Satwant Singh Kaleka was a farmer. His wife and their two small sons lived in a village near the city of Patiala, in the state of Punjab. He was a devout Sikh who would post religious writings on the walls of the home.

In 1982, Kaleka brought his family to the United States in search of opportunity. Like countless other immigrant families, he worked long hours at hard, manual-labor jobs to provide for his family. Still, they had to move around a lot.

By 2012, though, the Kalekas had made the Milwaukee area their home. Satwant Singh Kaleka had made a stable home for his family. He had become a grandfather. He was president of the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin — a faith community he had founded in 1997 and into which he poured time and energy in its early years.

On August 3 of that year, Pardeep Kaleka, one of Satwant’s sons, turned 36. For Pardeep, seeing his father that day was an opportunity to reflect on how far the family had come.

“He worked his entire life to not only create a sanctuary for himself and his family, but a sanctuary for the (Sikh) community itself,” Pardeep Kaleka said. “And by that time, he had completed that.”

It was the last time Pardeep would see his father alive. Two days later, a white supremacist gunman entered the Sikh temple in suburban Oak Creek as Sunday services were beginning. He opened fire, killing six people, including Satwant Kaleka. He wounded four others, including a police officer. One of the temple members who was wounded that day would die from his injuries in 2020.

The Sikh Temple of Wisconsin marked the 10th anniversary of the shooting from August 4 to 7. Priests at the temple, or gurdwara, performed a 48-hour continuous prayer service. The temple also held educational events that were open to the public, including a candlelight vigil on August 5 in honor of those who died a decade ago.

It was a somber anniversary. But for some members of the Sikh community, it was also a source of frustration. The shooting in Oak Creek happened just two weeks after a mass shooting at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado. Four months later, a gunman killed 27 people, most of them children, in an elementary school in Newtown, Connecticut. The decade that followed would see a massive increase in the number of mass shootings in America. And from a Black Episcopal church in South Carolina to the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, it would also see more terror attacks by white supremacists on minority houses of worship.

“Honestly, sometimes it feels like what happened in Oak Creek was ignored,” Harpreet Singh Saini said during a Congressional briefing. His mother was killed in the 2012 attack.

10 years later, shooting “feels like it just happened”

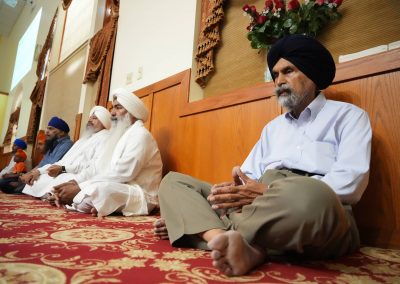

Today, some 300 families are members of the Oak Creek gurdwara. It hosts services on Wednesday evenings and Sunday mornings, always accompanied by a community meal of saffron rice, fried dumplings and other Indian dishes. The members of the gurdwara sit on the floor to eat, a symbol of humility and equality.

Male practitioners of the religion are recognizable for their turbans, which cover unshorn hair, both of which are tenets of Sikhism. Not all men in the religion wear turbans, but for many adopting the turban and beard is a rite of passage that comes later in life, and a sign of devotion to the religion’s values of service to others and protection of the community.

Within the temple, gurdwara members and other visitors are required to remove their shoes and cover their heads. In a library room off the main worship hall there are large portraits of the founders of Sikhism, known as the 10 gurus.

On another wall are portraits of the five men and one woman who died on August 5, 2012.

On that day, the gunman arrived around 10:30 a.m., near the beginning of the Sunday service but before most families had gotten there. He killed two brothers, Sita and Ranjit Singh, in the parking lot in front of the building. Inside, he shot others. A group of women huddled in the pantry, terrified, and he passed by them.

Brian Murphy was on patrol for the Oak Creek Police Department at the time. He arrived at the temple less than two minutes after the call came in. But he didn’t know what had happened; the dispatcher said it could have been a fight or some other interpersonal dispute.

Murphy saw someone run out of the temple’s front door.

“I yelled, ‘Police, stop!'” Murphy said. “And then his hand pops up with the gun in it and we both shoot.”

Murphy missed. The gunman would shoot him 15 times. He said it’s a miracle that he is still alive. Another officer who arrived minutes later, Sam Lenda, did shoot the gunman, who then fatally shot himself.

Pardeep Kaleka was running late to the temple that day, and he and his young family were stopped at the police roadblock. Soon, hundreds of community members had gathered at a bowling alley across the street. One by one, police asked family members to identify the dead. Kaleka heard from his mom. He began to understand that his father had not survived.

“My father would do anything and everything to make it back to his community, to his family,” Pardeep Kaleka said. “He was the most determined man I’ve ever seen. … I knew before they ever made a notification that he was probably one of the people that died inside.”

Navi Gill, a nephew of Satwant Kaleka, was 18 and had just graduated from high school. Today, he’s a medical student. As much as his own life and the rest of the world has changed, he said there are times when it feels like no time has passed at all.

“Some of the memories are so vivid, it feels like it just happened,” Gill said. “And then you realize, no, these people have been out of our lives for 10 years. And you miss them.”

After tragedy, members of the Sikh community dedicated themselves to service

The Sikh religion has a concept called seva, or service. One way that Sikhs across the country will observe the 10-year anniversary of the attack is with community service events. Advocates within the community are also lobbying Congress on three pieces of legislation related to protecting minority religious communities.

Sikh Coalition executive director Anisha Singh said Sikhs are asking Congress to take action on a bill that would authorize offices of domestic terrorism within the FBI and other federal agencies. Wisconsin Republican U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson objected to the bill when it came before the Senate earlier this year, and Republicans have filibustered it. Another would strengthen the enforcement of hate crime laws. A third law would provide grant funding for houses of worship that need to increase building security.

The anniversary “is a moment for introspective and reflection, but it’s also a call to action,” Singh said. “In 10 years, we can’t be having the same conversation or pushing for the same bare minimum of action we were pushing for 10 years ago and 10 years before that.”

For Pardeep Kaleka, the shooting would change the course of his life. He would ultimately leave his job as an educator to devote himself to combating extremism.

In the months that followed the shooting, he would ask himself an impossible question: What would make someone do something like this?

News media reporting on the shooting provided superficial answers. The gunman was an active member of hate groups. In the months before August 5, 2012, he had lost a house to foreclosure and his girlfriend had broken up with him. He didn’t leave a manifesto or a trail of writings online, but investigators believe he probably targeted the Sikh temple because its members are visibly different: mostly brown-skinned, some in turbans.

Kaleka reached out to a former White Supremacist in the Milwaukee area, Arno Michaelis, in an effort to learn about how people could be lured into extremist ideologies. The two became friends. They would start a service-oriented nonprofit for kids and write a book together, The Gift of Our Wounds: A Sikh and a Former White Supremacist Find Forgiveness After Hate.

Today, Kaleka’s main work is doing therapy for people who have been captured by extremist ideologies, to help them find a way out. He’s worked with white supremacists, Islamists, even eco-terrorists.

“Why I do this work is because I think as a society, we do not get upstream enough,” he said, “I’m trying to prevent the next Sikh temple shooter out there from hurting any community.”

He does that work because those are his values. But ahead of the 10-year anniversary of the shooting, he was clear-eyed about the challenges society still faces in fighting extremism, and the way the easy availability of guns has contributed to the rise in mass shootings.

“I fear we are still not understanding the severity of what we are going through right now,” he said, “We are going to go to a place where it gets much worse before it gets better.”

- Why the Sikh Temple massacre remains an inconvenient example of Milwaukee’s caring and complicity

- The enduring spirit of Chardi Kala: How Oak Creek’s Sikh community continues to share “eternal optimism”

- A Warning Unheeded: Terror attacks on places of worship increasing in spite of painful lessons

- Ride Against Hate: Sikh Motorcycle Club makes cross-country journey to Oak Creek for August 5 memorial

- Heal, Unite, Act: Pardeep Singh Kaleka on restoring hope 10 years after the Sikh Temple Tragedy

- Amaris Kaur Kaleka: I hope there comes a day when my generation can shop, learn, and pray without dying

- Tarina Ahuja: Reflections of a twenty-year-old from ten years after the 2012 Sikh Temple mass shooting

Rоb Mеntzеr

Lee Matz

Originally published as For Sikh community, 2012 Oak Creek shooting feels like a warning that wasn’t heeded