Near the end of 2018, then Governor Scott Walker publicly offered his rationale for signing Republican-backed bills passed in a lame-duck session of the Wisconsin Legislature that would constrain the power of future state executives, most immediately his successor, Democrat Tony Evers. Walker’s reasoning included a brief mention that governors going forward would retain one of the strongest veto powers in the nation.

Although the 2018 laws do restrict executive powers in various ways, Wisconsin’s top state office has extraordinary latitude to reshape bills — specifically appropriations bills — through the use of partial vetoes. These vetoes are similar to the line-item veto powers granted to governors of most other states, but Wisconsin’s partial veto is uniquely powerful. That difference is because, unlike in other states, governors in Wisconsin can strike nearly any part of a budget bill, including sentences, words or in some cases even a single character or digit.

This ability has allowed Wisconsin governors since 1930 to wield a quasi-legislative power to substantially — and sometimes controversially — alter the text and implications of appropriations bills with little if any legislative input.

“With these vetoes, when the governor makes his deletions, they effectively become law,” said Fred Wade, an attorney and legal historian based in Madison. An outspoken critic of Wisconsin’s partial veto, Wade described the veto’s history in a Sept. 15, 2009 talk hosted by the Wisconsin Historical Society and recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s University Place.

How did this extraordinary partial veto power come to be?

The story behind Wisconsin’s outsize veto authority begins in 1911, when the state Legislature began bundling appropriations bills for separate parts of the state government into what are called “omnibus” bills. By the late 1920s, this practice had evolved into a budget process largely resembling the modern procedure, whereby the governor would propose a state budget, and the Legislature would modify the proposal through a deliberative process and submit a final bill for the governor’s signature.

Early critics of the omnibus appropriations process worried that it bundled too many disparate concerns into one bill that a governor would be forced to either sign into law or veto in full. This approach unfairly strengthened the Legislature’s power over a governor’s, their argument held, by effectively forcing a governor to accept individual budget items that they may not support in order to pass the larger budget bill. This fear heightened in the late 1920s, when a new law required the governor to propose a single budget, effectively ending any possibility that a state budget could be passed piece by piece.

In an effort to rebalance powers over the state budget, state Senator William Titus, a Progressive from Fond du Lac, proposed a constitutional amendment in 1927 that would give governors the ability to veto pieces of an appropriations bill. At the time, more than 30 other states had line-item veto provisions similar to the one Titus proposed. He recruited Edwin Witte, who would eventually author the federal Social Security Act but at the time headed what is now known as the Wisconsin Legislative Reference Bureau, to draft the text of the proposal, which would amend Article V, Section 10 of the state constitution.

The proposed amendment read: “Appropriation bills may be approved in whole or in part by the governor, and the part approved shall become law.”

The amendment was passed by two successive Legislatures in 1927 and 1929, and in November 1930, it went before voters in a statewide referendum accompanying state and local elections.

The ballot question asked: “Shall the constitutional amendment, proposed by Joint Resolution No. 43 of 1929, be ratified so as to authorize the Governor to approve appropriation bills in part and to veto them in part?”

The referendum followed a brief but passionate public campaign aimed at its passage, which was led by state Senator Thomas Duncan, a Socialist from Milwaukee. He disseminated talking points through Wisconsin newspapers and lobbied interest groups to back the proposal.

Duncan opened his campaign for the ratification of the amendment at the Hotel Loraine in Madison in a speech before the American Businessman’s Club.

“I always think this is an interesting image,” said Wade, “of a Socialist from Milwaukee going in to talk to the American Businessman’s Club, and say[ing], ‘You know, what we need in this state is a partial veto … this is not a radical proposal.'”

Shortly thereafter, voters ratified the amendment by a nearly 2-to-1 margin, approving it as a solution for restructuring budgetary powers that had been tried and tested by dozens of other states. What no one seemed to realize at the time was that the language of the amendment — specifically its hinging on the vague term “in part” — created a partial veto authority in Wisconsin unlike any other in the nation. This difference would prove to be increasingly consequential and contentious in the decades to come.

The first Wisconsin governor to make use of a partial veto was Philip La Follette, a progressive Republican who had previously campaigned against its ratification.

According to the Legislative Reference Bureau, La Follette’s first partial vetoes were to several items in a 1931 appropriations bill. The vetoes targeted whole budget items, reflecting the shared understanding among his contemporaries that the partial veto’s intent was simply to allow governors to strike individual, but entire, appropriations from a bill.

For the most part, governors over the next four decades were similarly conservative in flexing their partial veto powers.

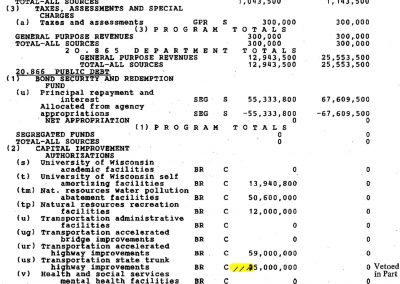

Then, beginning with Democratic Gov. Patrick Lucey in the 1970s, Wisconsin governors began interpreting the 1930 constitutional amendment more literally. They became increasingly selective and creative in their use of partial vetoes to advance their priorities when the Legislature hadn’t done so for them. One of these first instances was in 1973, when Lucey struck the digit “2” from a $25 million highway bonding authorization, effectively reducing it to $5 million.

In subsequent budgets, governors of both major parties became even more creative in their vetoes.

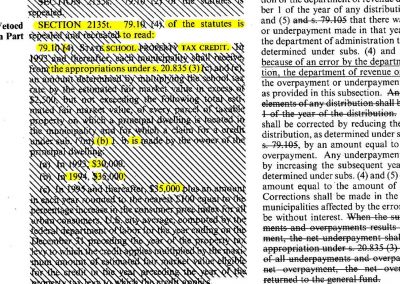

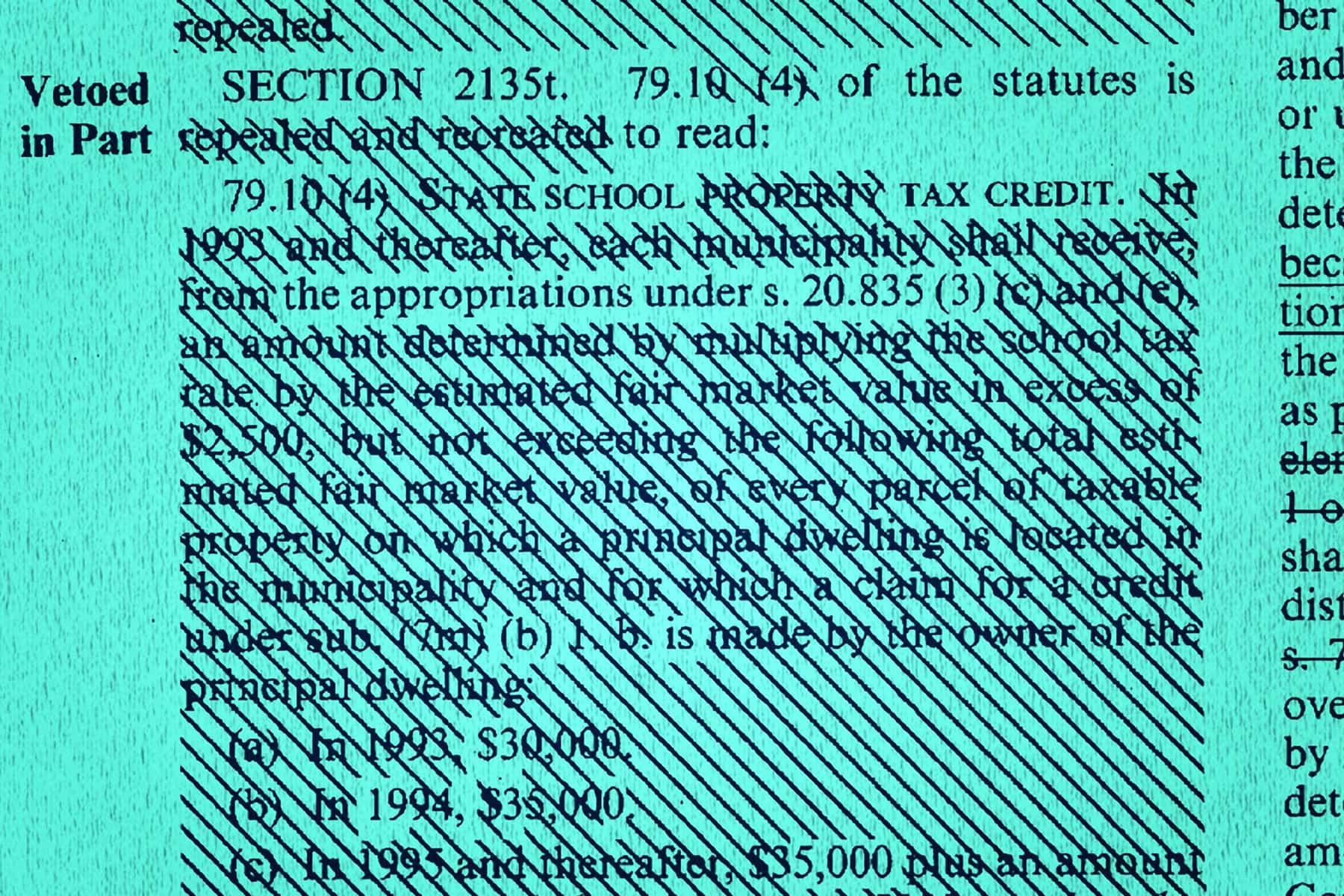

Wade pointed to a particularly memorable partial veto in the early 1990s by Republican Gov. Tommy Thompson, who took an expansive view of the power. The veto concerned a proposed appropriation toward a state school property tax credit in the 1991-1992 state budget. The Legislature had approved an appropriation that would authorize the state to reimburse municipalities for tax credits claimed by local property owners on up to $35,000 of the value of their properties. Thompson struck most of the provision, including individual digits in years and monetary values, to arrive at a brand new appropriation of $319,305,000 for a school tax credit fund.

“This is a $319 million appropriation that the Legislature plainly did not approve, in fact did not consider, let alone enact,” Wade noted. “But it was treated as if it was a law passed and approved by the Legislature, and over 4 years, before the Legislature got around to amending that legislation, resulted in the spending of $1.2 billion that the Legislature did not authorize to be spent, at least for that purpose.”

Thompson’s action in this instance became known as the “Frankenstein veto,” a practice also taken up by subsequent governors.

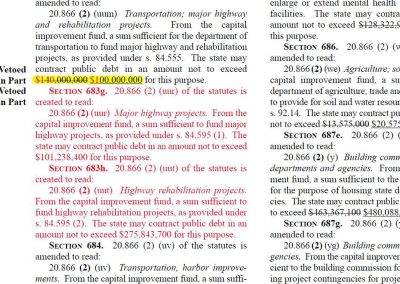

Since Thompson, Wisconsin governors have partially vetoed scores of appropriations bills, sometimes even using the vetoes as bargaining ploys. Wade recounted a veto by Democratic Gov. Jim Doyle in a 2003 budget bill in which he transformed a proposed $100 million appropriation for transportation funding into a $1 billion appropriation.

“The Legislature got mad about this particular veto … and threatened a lawsuit,” Wade said. “They worked out a compromise, [and] they passed a replacement for this that authorized about $500 million in bonding authority. So, the governor got what he wanted … and the Legislature got to say, ‘Well, we did something about that particular veto.'”

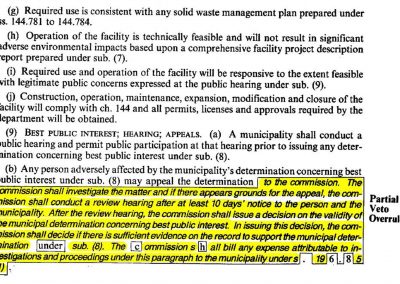

Disputes over the legality of such partial vetoes have escalated into eight Wisconsin Supreme Court cases over the decades — six of which expanded the partial veto power — as well as two further constitutional amendments that restricted partial veto powers to a degree.

Early state Supreme Court cases in the 1930s and 1940s centered on the legality of specific partial vetoes, and the Court’s decisions almost always defended an expansive view of the power.

This sweeping interpretation was galvanized in a 1995 case, Citizens Utility Board v. Klauser, in which the state Supreme Court closely examined the original amendment’s text. Specifically, the court considered the Webster’s dictionary definition of the word “part,” given its centrality to the partial veto powers bestowed in the amendment.

In a 4-3 decision, the court upheld a partial veto of Gov. Tommy Thompson in which he struck an appropriation and replaced it with a lower value, known as a “reduction veto.”

The majority’s opinion stated: “As relevant here, the court quoted the following dictionary definition of the word: ‘Something less than a whole; a number, quantity, mass, or the like, regarded as going to make up, with others or another, a larger number, quantity, mass, etc.'”

The majority continued: “Applying this definition to the situation at hand, it is readily apparent that $250,000 is ‘part’ of $350,000 because $250,000 is ‘something less than’ $350,000, and $250,000 goes ‘to makeup, with others … a larger number,’ i.e., $350,000. This ‘common sense’ reading of the word part, in terms of appropriation amounts, is what we believe is intended.”

This opinion followed a 1990 constitutional amendment that had restricted the use of the partial veto so that governors “may not create a new word by rejecting individual letters in the words of the enrolled bill.” This amendment ended a practice — known as the “Vanna White” veto — that had begun under Democratic Governor Tony Earl and continued under Thompson.

More recently, a 2008 constitutional amendment ratified by Wisconsin voters disallowed the so-called Frankenstein veto, or “crossing out words and numbers to create a new sentence from two or more sentences.”

Even considering these amendments, Wisconsin governors remain able to cross out words and digits within a sentence — so long as they do not create new words — and maintain most expansive partial veto power in the nation. And it’s an authority that doesn’t seem to be going by the wayside anytime soon, even as new efforts in the state Legislature seek to blunt its impact. Still, as Wade noted, the Legislature has not attempted to uproot the partial veto in its entirety.

“[O]ur legislators have not seen this as an issue that ought to be dealt with by completely eliminating the governor’s power to create laws the legislature did not approve,” Wade said.

Will Cushman

Wisconsin State Legislature

Originally published on WisContext.org, which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.