It was 1969. The last year for President Kennedy’s pledge to land a man on the moon and return him safely “before this decade is out”. NASA was not sure it could be done in time. There were, perhaps, going to be only three opportunities before the deadline expired.

On 6 January the head of the astronaut office at NASA, Deke Slayton, called the crew of Apollo 11 – Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin and Michael Collins – into his office in Houston, Texas, and told them that their mission, set for July, might involve a lunar landing. A few weeks earlier, Apollo 8 had taken the first crewed voyage around the moon, and the tasks of the forthcoming Apollos 9 and 10 were set. Apollo 9 was to test the lunar landing spacecraft in Earth orbit and Apollo 10 was a full rehearsal at the moon – everything except the landing itself.

The crew of Apollo 11 were introduced to the press on 9 January and immediately the assembled reporters got down to the big question: “Which of you gentlemen will be the first man to step out on to the lunar surface?”

It is clear that for the first few months of 1969 Aldrin believed that he would be first. He said he had never given it much thought and that he had naturally presumed it would be him. He was perhaps right to believe it: NASA’s associate administrator for manned space flight, George E Mueller, had told several people, including some members of the press, that he would make the first footprint.

But word began to filter out that it would be Armstrong. Aldrin was angry: Armstrong was a civilian. It would be an insult to the service. He himself was technically still a member of the air force, though he had not served for 10 years, except to maintain his flying hours. So he approached Armstrong. Aldrin wrote later – although he claimed it was done by his co-author: “He equivocated a minute or so, then with a coolness I had not known he possessed, he said that the decision was quite historical and he didn’t want to rule out the possibility of going first.” Armstrong later said that he could not remember the conversation.

Aldrin talked to colleagues; for some it was seen as lobbying behind the scenes. Gene Cernan (the last person to walk on the moon) said: “He came flapping into my office at the Manned Spaceflight Center one day like an angry stork, laden with charts and graphs and statistics, arguing what he considered to be obvious – that he, the lunar module pilot, and not Neil Armstrong, should be the first down the ladder on Apollo 11. Since I shared an office with Neil Armstrong, who was away training that day, I found Aldrin’s arguments both offensive and ridiculous.”

That was not the way Aldrin saw it. Writing some 40 years later in his book “Magnificent Desolation,” he said that during training in early 1969 he recognized that the great responsibility would fall upon his shoulders. In all the previous Gemini and Apollo missions, the spacewalks were taken by the junior officer while the commander remained inside the space capsule.

As of February 1969 that was their plan as well, Aldrin maintained. He said that he hadn’t been soliciting the older astronauts’ support. He was simply behaving as a competitive air force pilot would. “In truth I didn’t really want to be the first person to step on the moon. I knew the media would never let that person alone.”

On 14 April the speculation came to an end. At a press conference NASA announced that the “plans called for Armstrong to be the first man out after the moon landing; a few minutes later Colonel Aldrin will follow.” Aldrin later said he believed that the layout of the lunar module dictated that Armstrong go out first because he was on the right and the door swung towards Aldrin. But that was not the case. It could technically have been Aldrin – they just had to swap sides before they put their backpacks on.

Later, flight director Chris Kraft explained NASA’s thinking. He said they knew damn well that the first guy on the moon was going to be a modern-day Charles Lindbergh. Armstrong was calm, quiet and had absolute confidence. He knew he was the Lindbergh type. He had no ego. On the other hand, Aldrin desperately wanted the honor and was not quiet in letting it be known. Kraft added that nobody criticized Aldrin but that they did not want him to be humanity’s ambassador. “The hatch design didn’t come into it. That was a rationalization, a solace for Buzz.”

During the first half of 1969 there were times when things did not go, as NASA would say, optimally. When Apollo 10 took off in May for the dress rehearsal flight, Armstrong and Aldrin were spending up to 14 hours a day in the landing simulator at Cape Kennedy, flying home to their families in Houston at weekends. Those around them were worried they were training themselves into exhaustion and some wondered how long they could continue. Janet Armstrong said that her husband frequently came home with a face that had turned white. By June it was clear that their morale was down. Each one wondered if there was enough time to learn everything.

NASA’s new administrator, Thomas Paine, was also worried. Before he set off for the Paris Air Show he asked the Apollo program director, Sam Phillips, if he was concerned about the crew. Shortly afterwards, Phillips called a flight readiness review meeting using telephone conference calls to ask whether they were pushing the crew too hard. “I’m fully prepared to delay if something is not ready,” he said.

Charles Berry, the director of medical research and operations in Houston, said he was concerned about the crew and would welcome a delay to the mission. Also on the conference call was Deke Slayton, who determined crew assignments. He said that Armstrong had told him that yes, the schedule was tight and yes, they were exhausted, but the pace would slacken in early July and they would rest then. The meeting decided that Apollo 11 could go ahead with the landing and this was announced to the public the day after. Janet Armstrong saw her husband’s mood improve.

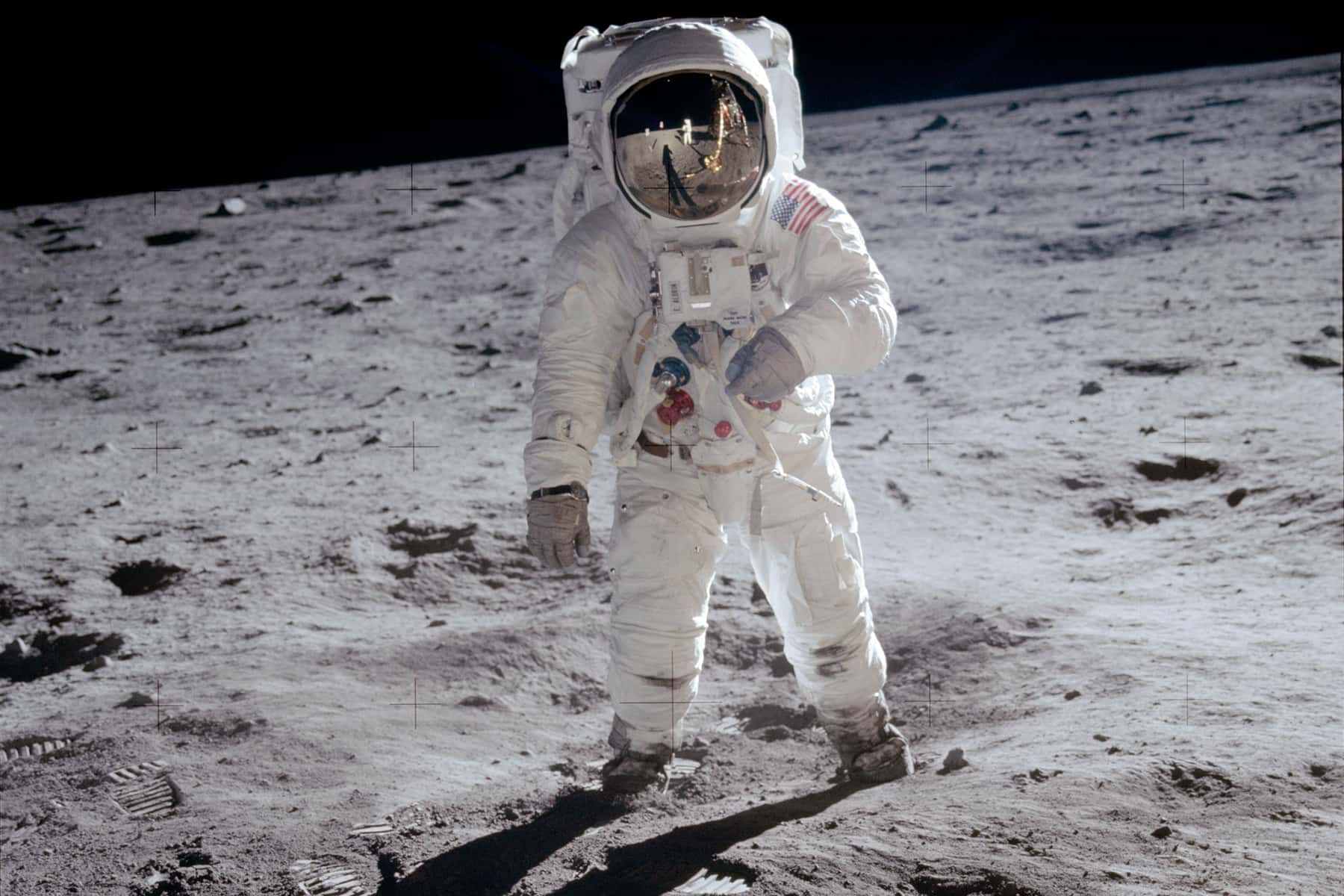

On 20 July they were in lunar orbit. Armstrong and Aldrin entered the lunar module, dubbed Eagle, to undock and begin the landing. Neither of them had been in the simulator for about two weeks. After the initial part of the descent they performed the so-called pitch-over maneuver, allowing them for the first time to see the moon below. They did not recognize anything. They were heading for a big boulder field, flying a trajectory they had never flown in the simulator.

Back at Mission Control, capsule communicator Charlie Duke said it was something they had never seen: “You know, Armstrong’s just whizzing across the surface at about 400ft, and all of a sudden, the thing rears back and he slows it down and then comes down.” Flight director Gene Kranz said: “We’ve never seen anybody flying it this way in training.”

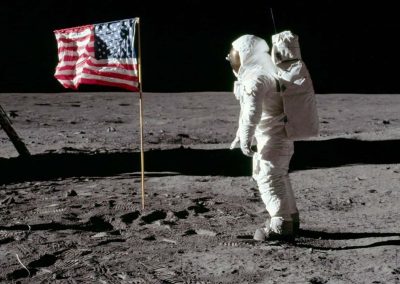

It was Armstrong’s moment. The greatest test for a pilot in history. He delivered, and deserved the first footprint.

David Whitehouse, author of Apollo 11: The Inside Story by Dr David Whitehouse

NASA

Originally published on The Guardian as Apollo 11: the fight for the first footprint on the moon

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.