“In recent decades, there has been remarkable growth in scientific research examining the multiple ways in which racism can adversely affect health. This interest has been driven in part by the striking persistence of racial/ethnic inequities in health and the empirical evidence that indicates that socioeconomic factors alone do not account for racial/ethnic inequities in health. Racism is considered a fundamental cause of adverse health outcomes for racial/ethnic minorities and racial/ethnic inequities in health.” – Racism and Health: Evidence and Needed Research Study (2019)

It did not take the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor or Ahmaud Arbery for Black folk to become woke. Black people in this country are in a state of perpetual sleeplessness. We can’t go to sleep without one eye open in America. To do so could lead to premature death. The pandemic did not awaken us to health disparities, we live that every day of our lives. Police and White vigilante violence are a constant, common thread in our lived experience. These things which woke White people up, only added further evidence to our case that Black lives don’t really matter in America. For several years I have done a presentation I call Do Black Lives Matter?: The Historical Devaluation of Black Lives in America to document this history.

A Black physician, Dr. Susan Moore, died of COVID-19 less than a week before Christmas after documenting, in a now viral video, that she was treated poorly after going to a hospital in Indiana a few weeks ago with COVID symptoms. In the video she says, “I put forth and I maintain if I was White, I wouldn’t have to go through that.” She described how a White doctor dismissed her complaints of pain as well as concerns about her treatment. She posted the video of the encounter at Indiana University Health North Hospital on social media on December 4. She said her doctor brushed off her symptoms, saying to her, “You’re not even short of breath.” “Yes, I am,” she retorted to the doctor.

Three days before Christmas, 47-year-old Andre Maurice Hill was shot to death by Officer Adam Coy in Columbus, Ohio just seconds after the officer arrived to investigate a so-called suspicious vehicle. Hill had an illuminated cell phone in his left hand when shot by Coy. The Police Chief, Thomas Quinlan has already stated “I have seen everything I need to see, to reach the conclusion that Officer Coy must be terminated immediately. Some may call this a rush to judgment. It is not. This violation cost an innocent man his life.” Add him to the long list of unarmed Black men killed by police.

These two incidents mean that 2020 ends much as it began. Not much has changed despite the “wokeness” about disparate treatment of Blacks in healthcare and police violence. It feels like the movie Groundhog Day for Black people.

It is not a revelation that racism causes major issues for Black people in America. We have known how bad racism is for our entire existence in America. It is interesting that it took this horrible year for America to begin to understand how deadly racism is. Racism has been killing Black people in this country for so long that it seems normal that we live shorter lives than other people.

It is not normal. This shorter lifespan is part and parcel of a system that has been designed to keep us in an inferior position. The impact of racism on Black people is by design. It leads us to, in many instances, not placing a great deal of value on the lives of those in our community. People in oppressed communities have always murdered their peers disproportionately because they’ve been taught to see themselves as inferior. Adding to this, the many other ways our lives are shortened, creates a massive loss of life unnecessarily.

The extreme health disparities we face played a role in how the SARS-coV-2 virus devastated our community in the first several months of the pandemic. Those with preexisting heath conditions were more susceptible to severe illness and death when exposed to this virus. Blacks have much higher rates of the type of conditions which worsen COVID. We are much more likely than Whites to have to work in so-called essential jobs which put us at greater risk of exposure. Those within the Latino community face similar problems with essential jobs. Native Americans suffer from a lack of access to healthcare. Black people’s experiences with disparate treatment within the health care system in this country is instructive when trying to understand why the pandemic has been so much worse for us, particularly in the early months of the pandemic.

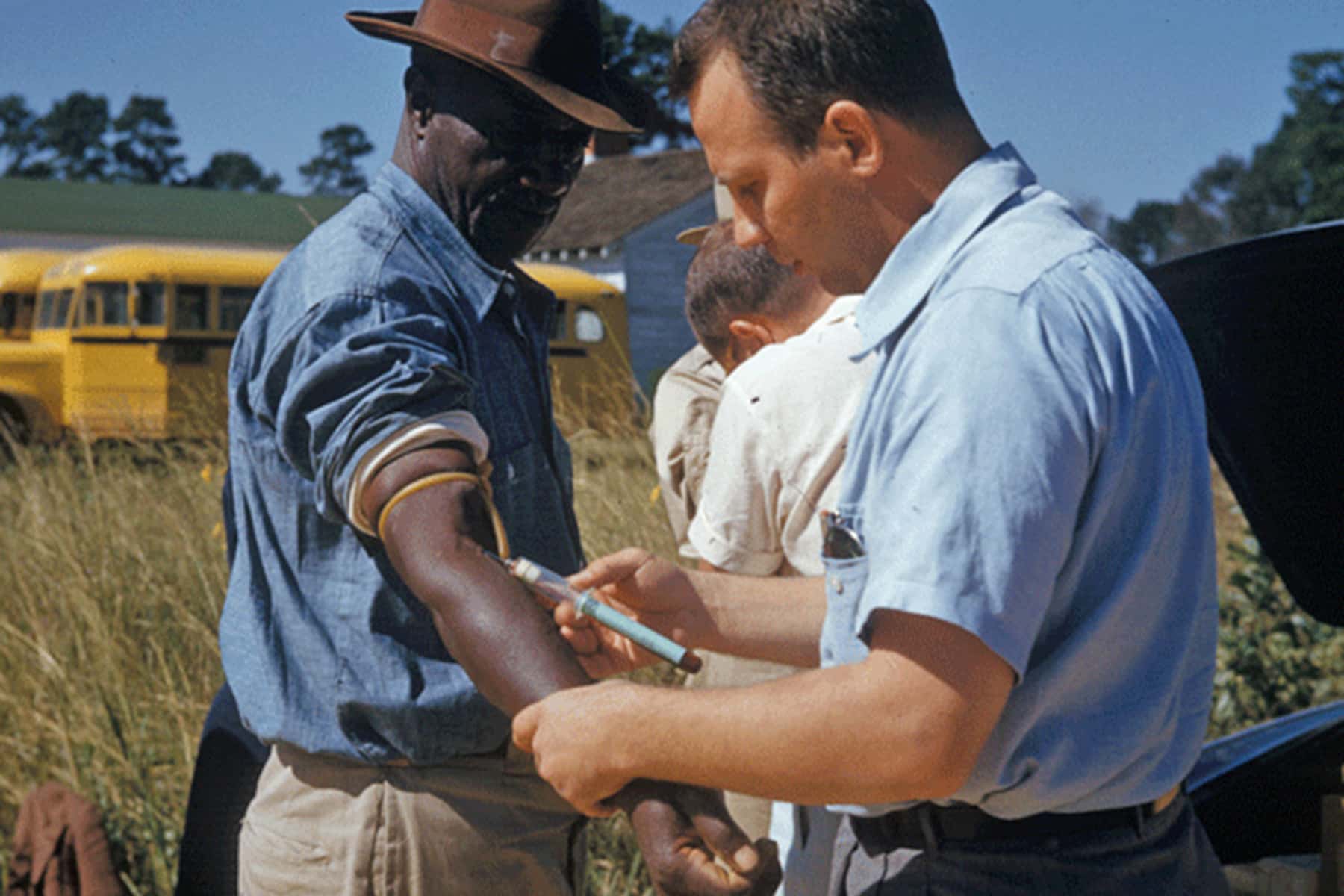

There has been a lot of discussion in recent weeks about whether members of the Black community will willingly take the vaccines for this COVID disease. Many have written about the reasons for distrust by our community of the medical establishment. Almost all have spoken about the “Tuskegee Effect.” What they miss, is that Black people distrusted the system for centuries before Tuskegee was exposed in 1972. Discriminatory treatment in medicine is our norm even to this day. Despite the story being out there for nearly fifty years, many don’t know the details of Tuskegee.

I would like to detail that horrible “experiment” because it was much worse than what most people understand about it and to also show some of the other reasons, above and beyond Tuskegee, why Black people don’t trust the system with good reason.

Records at the National Archives provide background on the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.” It began in 1932 with 600 Black men, 399 with syphilis and 201 without, as a control group according to most accounts of the study. Records from the National Archives show that 411 men with syphilis and 200 without were the actual number at the beginning. From 1938-39 14 additional men were added to the study leaving a total of 425 with syphilis. Nine more men in the control group contracted syphilis and an additional nine men were reclassified from the control group and were added to the group with syphilis after testing showed they had syphilis also. This meant that in the end just 182 were left in the control group and 443 were in the group with syphilis. At year end 1968, a total of 373 participants had died (97 from control group and 276 from syphilitic group). Of the 125 men left, eighty-nine were examined (36 controls and 53 syphilitic). According to a 1968 report of these examinations:

“All of the patients examined in 1968 were less than 55 years of age at initial examination and the syphilitic group, for the most part, represented survivors from the diagnostic categories of latent syphilis or possible cardiovascular syphilis. When examined in 1968, 51 of the 53 were diagnosed with latent syphilis, 1 neurosyphilis and 1 cardiovascular.”

Of the 276 with syphilis who had died, 160 had been autopsied. These autopsies showed that in the early stages of the study, syphilis was diagnosed in 77 percent of the autopsies performed from 1932-1939 but only 27 percent of those done from 1963-1968. Many of the men who died developed cardiovascular disease (55.8%) within the syphilitic group which without doubt contributed to their deaths. As you will see, cardiovascular disease is one of the ramifications of having long-term untreated syphilis.

James H. Jones in his book on the study, Bad Blood: The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment wrote about the lack of ethics during the study.

“The Tuskegee Study had nothing to do with treatment. No new drugs were tested; neither was any effort made to establish the efficacy of old forms of treatment. It was a non-therapeutic experiment, aimed at compiling data on the effects of the spontaneous evolution of syphilis on black males.”

It was a program of the United States Public Health Service (PHS). All of the men in the study were from the region in and around Macon County, Alabama and were in the late stage of the disease when the study began. Tuskegee is the county seat of Macon County and the home to Tuskegee Institute which participated in the study. The PHS was able to enlist Black church leaders, elders from the community, and many plantation owners to encourage participation in the study.

When the story of the “experiment” broke in July 1972 with an article by Jean Heller of the Associated Press many questions were asked about what happened. One of the first questions asked by reporters was where was the formal protocol when it began. There was not a formal written protocol, it developed over time.

One of the elements of this “experiment” and many others over time is the Nuremberg Codes were not used in the United States for Blacks involved in medical experimentation. Natalie Jarmusik wrote about the Nuremberg Codes in 2019.

“When World War II ended in 1945, the victorious Allied powers enacted the International Military Tribunal on November 19th, 1945. As part of the Tribunal, a series of trials were held against major war criminals and Nazi sympathizers holding leadership positions in political, military, and economic areas. The first trial conducted under the Nuremberg Military Tribunals in 1947 became known as The Doctors’ Trial, in which 23 physicians from the German Nazi Party were tried for crimes against humanity for the atrocious experiments they carried out on unwilling prisoners of war.”

The Nuremberg Codes became a set of ten ethical principles for human experimentation developed after the trial. Six of the ten principles should have applied directly to Tuskegee: Voluntary consent is essential; The results of any experiment must be for the greater good of society; Experiments should be conducted by avoiding physical/mental suffering and injury; No experiments should be conducted if it is believed to cause death/disability; The risks should never exceed the benefits; The scientist in charge must be prepared to terminate the experiment when injury, disability, or death is likely to occur.

These codes were violated time and time again in this atrocious study. Fifteen years into the study, international rules were in place to protect the participants based on the Nuremberg Codes. Their lives did not matter enough for the many doctors, nurses and public health officials involved.

During the forty years, the men were told they had “bad blood” and believed they were receiving treatment for this malady. The PHS intentionally chose men with tertiary stage (3rd stage) syphilis because they wanted to learn what the last stage of the disease did.

The first stage of the disease generally lasts 10-60 days after infection and chancre sores been to appear on the genitals. Eventually the chancre which is not always visible heals, leaving a scar that will last several months.

Somewhere between six weeks and six months long, the second stage is recognizable by a rash, pain in the joints and heart palpitations. Sometimes these rashes spread through the blood to the mouth causing a great deal of pain. Hair loss is common in this most active stage of the disease.

After a period of latency they may last up to 30 years the third stage begins to manifest itself. During the latency period none of the previous symptoms will be visible. During this latency, the disease causes chest pains, and vision issues among other things. All the while it spreads into the lymph glands, bone marrow, central nervous system and multiple organs. In most patients this latency last about two to three years.

By far the most difficult stage is stage three. Tumors develop, often forming large ulcers on the skin. The bones are attacked, the nasal passages are eaten away and the liver is scarred. The heart and blood vessels are damaged. The heart walls and valves are slowly destroyed leading to aneurysms and sudden death as was documented in the 1968 report I quoted above. The brain is also attacked by the disease. Jones wrote:

“The results of neurosyphilis are equally devastating. Syphilis is spread to the brain through the blood vessels, and while the disease can take several forms, the best known is paresis, a general softening of the brain that produces progressive paralysis and insanity… Syphilis can also attack the optic nerve, causing blindness, or the eighth cranial nerve, inflicting deafness. Since nerve cells lack regenerative power, all such damage is permanent.”

One of the common beliefs at that time was that the brains of Blacks and Whites were different. The study was designed to see on the autopsy table what the disease did to these Black mens brains. Syphilis was well understood by the time the study began in 1932. All of the destructiveness was clearly known, yet the hundreds of people involved over forty years had no qualms about making these men and their partners and children suffer horribly. Women and children were devastated by this disease as the men were refused treatment. The men with syphilis unknowingly passed it along to their sexual partners. Babies were born with horrific birth defects and the experiment continued unabated. What was the reward for the victims of the study? Jones tells us what they received for taking part.

“The men received free medical examinations, free rides to and from the clinics, hot meals on examination days, free treatment for minor ailments, and a guarantee that burial stipends would be paid to their survivors. Though the latter sum was very modest (fifty dollars in 1932 with periodic increases to allow for inflation)…”

The study ended with each subject when they were autopsied. Over the many years of the study the men were given periodic blood tests, and clinical examinations. They were not supposed to be given medicine for the disease because the experiment was designed to see what untreated syphilis would do to their bodies.

Dr. J.W. Willams an intern at Andrews Hospital at the Tuskegee Institute in 1932 assisted in the clinical work and testified later:

“The people who came in were not told what was being done. We told them we wanted to test them. They were not told, so far as I know, what they were being treated for or what they were not being treated for… (the subjects) thought they were being treated for rheumatism or bad stomachs…We didn’t tell them we were looking for syphilis, I don’t think they would have known what that was.”

The study only ended because the doctors and public health officers became concerned that the experiment would become public. They were not concerned about the damage they had inflicted on these poor Black men. In late 1970, Dr. James B. Lucas, assistant chief of the Venereal Disease Branch of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) said these infamous words about the study:

“Nothing learned will prevent, find, or cure a single case of infectious syphilis or bring us closer to our basic mission of controlling venereal disease in the United States.”

This was the first time someone involved had stated the obvious. He went on to say one of the issues with the study is that somehow many of the syphilitic men had actually been given penicillin during the study. As a result, the study’s value had been undermined “because effective and undocumented treatment has been given to the vast majority of the patients in the syphilitic group.” He is literally saying the study of untreated syphilis was ruined by giving the men penicillin. He went on to state, “Probably the greatest contribution that the Tuskegee Study has made and can continue to provide has been documented sera for study in our laboratory.” The suffering of these men over decades offered blood samples to continue to be studied by the CDC. That’s the only value this doctor saw in the sacrifices these men made. He and his colleagues had no desire to end the study. He suggested that the experiment “be continued along its present lines with periodic clinical observation and serologic surveillance.”

Along came Peter Buxtum, a venereal disease interviewer and investigator for the PHS in San Francisco. He heard co-workers at the Hunt Street Clinic openly discussing the study over lunch. He was flabbergasted. He decided to write an article on the study as part of his job writing about venereal diseases. After looking at multiple reports written to the PHS over years by those involved in the study, in November 1966 he sent a letter to the director of the CDC’s Division of Venereal Diseases, Dr. William J. Brown questioning the ethics of the study.

Buxtum was eventually sent to Atlanta to discuss his concerns with the CDC director, and several others including Dr. John Cutler who had been intimately involved in the study. Cutler first told Buxtum he was a lunatic for questioning the study and then finally tried very hard to defend the study. It did not work. Buxtum stood his ground. He was not fired but resigned the following year. He wrote a second letted to Dr. Brown a year later. He made it clear that the fact that all the subjects were Black could easily add to a combustible atmosphere with race relations being in a bad place in the late 1960s.

In February 1969 a blue-ribbon commission was convened to discuss the study. The committee consisted of: Dr. Gene Stollerman, Chairman of the Department of Medicine at the University of Tennessee; Dr. Johannes Ipsen Jr., Professor in the Department of Community Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania; Dr. Ira Myers, State Health Officer of Alabama; Dr. J. Lawton Smith, Associate Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Miami; Dr. Clyde Kaiser, a senior member of the technical staff of Milbank Memorial Fund; Dr. Sidney Olasky, Professor of Medicine at the Department of Internal Medicine at Emory University and Dr. David J. Sencer, CDC Director and multiple other doctors and staff from the CDC. This was not just a run of the mill group.

In a report written about the meeting Dr. Sencer stated that they had been brought together to answer the question:

Should we terminate the study or should we continue it? It becomes a political problem. At the time the Study was begun there was no concern about racial problems, discrimination etc. At that time there was no problem about not treating the disease. “We wan’t your advice in making a decision. We are here to discuss this problem.”

Among the many things discussed were multiple written reports and evaluations of the past thirty-seven years, the active role Black public health Nurse Eunice Rivers played, autopsy reports and medical findings. Dr. Smith said during the meeting “You may find seronegative patients in this group. But I don’t think it will make any difference whether you treat them or not.” They had taken pictures of the subjects eyes during optical exams. Dr. Smith said “20 years from now, when these patients are gone, we can show these pictures.”

When it came time to discuss renumeration to the patients still in the study, Dr. Smith suggested giving them $200 each “I think an investment of $13,000 would be to get the examinations.” Dr. Meyers suggested they be paid 50 cents a week until they die. Dr. Sencer complained that Nurse Rivers had gotten old and often got lost going to visit the participants. In the end, the group decided there was “merit” in continuing the study. Only Dr. Stollerman seemed to care about the survivors of the study. He was the only one who pushed to treat the patients. The committee overrode his suggestion and decided against offering treatment of any kind.

In July 1972 Buxtum contacted reporter Edith Lederer of the Associated Press in San Francisco. It was his second attempt to get them to investigate and write about Tuskegee. He gave them all of the evidence he had acquired. Eventually the story was given to Jean Heller an Associated Press reporter in Washington DC because she was closer to Tuskegee. Heller was able to interview people at the CDC who openly talked to her with no fear of negative publicity. On July 25, 1972 her story broke in the Washington Star. It spread like wildfire.

The following day an investigation was launched by Dr. Merlin K. Duval, assistant secretary for health and scientific affairs of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Many of the doctors and other officials involved were exposed and made excuse after excuse for their behavior.

Famed civil rights attorney Fred Gray filed a $1.8 billion class-action civil rights suit on behalf of the victims. He demanded $3 million in damages for each living participant, and the same amount for the heirs of the deceased. He also asked for an injunction to end the experiment. The defendants in the suit were the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare, The United States Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control, the state of Alabama, the state board of health for Alabama, and the Milbank Fund.

In 1974 a $10 million out-of court settlement was reached. Each living syphilitic participant received $37,500, the heirs of those syphilitics who were deceased received $15,000, each living member of the control group received $16,000 and their heirs got $5,000. Under Alabama law, only legitimate children could receive compensation resulting in many illegitimate children being left high and dry, fracturing relationships between siblings who often lived in the same homes with those who received payments.

Ultimately there was no contrition shown by officials from the PHS. They claimed to have acted in good conscience and it was clear they would have proceeded along the same path if given an opportunity to do it all again. Nurse Rivers felt the only mistake made in the forty years was “The doctors didn’t tell the patients they had syphilis.” She never believed the men were harmed by the “experiment.” Survivors had a different take. One called himself and others “guinea pigs” and another said “I don’t know what they used us for. I ain’t never understood the study.”

It was truly a sad episode in the history of the health care system. No one was held accountable for this so-called experiment, no one lost their jobs or had their careers damaged by participating. These men and women took advantage of these mostly illiterate men for four decades and showed no remorse. No one cared that their lives had been filled with unimaginable pain and suffering. The pittance they received cannot be called reparations as some have referred to it as. No one repaired the damage done because it was impossible to do so.

This episode still reverberates in the Black community today with many swearing the men were given syphilis. The distrust of healthcare workers and researchers that was already so prevalent was exacerbated by Tuskegee. This experiment was simply an extension of how Blacks had been treated since they arrived in this land 401 years ago. It was not an aberration. It was business as usual.

Blacks have been treated as less than human by the medical community for generations and continues to receive discriminatory care on a daily basis. Harriet Washington’s groundbreaking 2007 book, Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans tells a long story of this ugly history. The publisher says this about the book:

“From the era of slavery to the present day, starting with the earliest encounters between Black Americans and Western medical researchers and the racist pseudoscience that resulted, Medical Apartheid details the ways both slaves and freedmen were used in hospitals for experiments conducted without their knowledge — a tradition that continues today within some black populations. It reveals how Blacks have historically been prey to grave-robbing as well as unauthorized autopsies and dissections. Moving into the twentieth century, it shows how the pseudoscience of eugenics and social Darwinism was used to justify experimental exploitation and shoddy medical treatment of Blacks. Shocking new details about the government’s notorious Tuskegee experiment are revealed, as are similar, less-well-known medical atrocities conducted by the government, the armed forces, prisons, and private institutions… It provides the fullest possible context for comprehending the behavioral fallout that has caused Black Americans to view researchers—and indeed the whole medical establishment — with deep distrust.”

The fact that Blacks continue to receive inferior care is borne out in study after study. The 2003 study Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care documented how often non-white patients are given inferior care by medical practitioners.

“At no time in the history of the United States has the health status of minority populations–African Americans, Native Americans and, more recently, Hispanics and several Asian subgroups–equaled or even approximated that of white Americans…racial and ethnic discrimination itself may be an important contributor to health disparities, not merely through the historic and persistent disadvantages it creates for minorities in the American social structure, but also specifically through health provider bias–conscious or unconscious, individual or institutional. A rich literature attests to the persistence and prevalence of racist beliefs and discriminatory behaviors in contemporary American society.”

David R. Williams is a Professor of Public Health and chair of the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health at Harvard University and one of the foremost experts on how racism has impacted the lives of Blacks due to inferior care. His work has focused on the detrimental impact of cumulative discrimination.

“We know that high levels of psychosocial stress can have serious health consequences—such as high blood pressure, asthma, obesity, cancer, and death, as well as damaging behaviors, such as poor sleep, smoking, and substance abuse. Such stress has been linked with facing racial discrimination—or even the threat of racial discrimination—on a regular basis, in everything from employment to getting a bank loan to hailing a taxi. Certainly the recent tragic events in the news would only serve to heighten individuals’ existing stress levels.”

The COVID pandemic has exposed what discrimination in healthcare leads to. A long-term distrust of and lack of access to the same level of care Whites take for granted leads the Black community to be sicker for longer periods of time and much more likely to die prematurely. The early months of the pandemic devastated the Black community. We contracted the virus at a higher rate, got sicker for longer periods of time and died at disproportionate rates. We are three times more likely than Whites to die from the coronavirus. Studies have shown that we still receive inferior care in the age of COVID treatment. We were less likely to be referred for testing in the early months of the pandemic.

According to a June study by Boston-based biotech research firm Rubix Life Sciences, Black patients that exhibited Covid-19 symptoms were six times less likely to receive testing or treatment, in comparison to White patients who exhibited symptoms. Across the country our community faced long waits on testing and treatment. NPR reported that, “In Nashville, three drive-through testing centers sat empty for weeks because the city couldn’t acquire the necessary testing equipment and protective gear like gloves and masks. All of them are in diverse neighborhoods. One is on the campus of Meharry Medical College — a historically black institution.”

For many months, states refused to prioritize making data available to see if there were differences across racial groups. It took months before that critical data was made available to the public. Still we have no national data or reliable state data showing the longitudinal dimensions of the pandemic as it relates to race. No one can tell you the breakdown of the COVID deaths from month to month broken down by race. We can’t see the trends in infection, hospitalization or deaths broken down by race nine months into the pandemic. This is shameful and there is no excuse for this. It is another impact of systemic racism in healthcare.

In light of all of this, some seem to think that now that vaccines are available that putting a video camera into the room when a Black person receives the vaccine is all it takes to remove the centuries of distrust we have. It will not work. We are not that naive. A Black Surgeon General, Dr. Jerome M. Adams getting a vaccine shot on camera will not assuage the fears many have of the vaccines.

It will take a great deal of time to build trust in these vaccines for many in our community. For some in our community they will never have that level of trust. The sins of the past always have an impact on the present. Unfortunately if the vaccines are found to truly be effective, Blacks will not benefit as much due to this distrust.

A long history of racism has led to premature death for Blacks in the form of: beatings that led to death during 246 years of enslavement; one hundred years of openly allowed extralegal killings during the one hundred years following the Civil War; police killings of unarmed Blacks that has awakened the nation and now the disparate impact of a pandemic.

2020 has simply provided further evidence that Black lives don’t matter the way White lives do. The fact that you can’t even say “black lives matter” without a boatload of White people getting upset says a lot about the state of race relations.

I will remember many things about this year but nothing will stand out more than the continuation of racism and how deadly that can be for Black people.

On November 16, 1972 the Tuskegee Syphilis Study was finally ended with these words:

“As recommended by the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Ad-Hoc Advisory Panel, I have decided that the “Tuskegee Study” as a study of untreated syphilis must be terminated.” – CDC Director Dr. Merlin K. Duval

It took forty years and exposure by Peter Buxum and Jean Heller to end this horrible human experiment which makes me wonder how long the continuing disparate treatment of Blacks will continue. Only when the day comes when we are treated equitably will we be in a position to begin trusting in the healthcare system and run out to be in line for vaccines like the ones that we are being begged to take today. I’m not sure that day will ever come.

“Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and the most inhuman because it often results in physical death.” – Dr. Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. (1966)

© Photo

National Archives at Atlanta and Tuskegee Syphilis Study Administrative Records