The Jewish Museum Milwaukee screened the film “From Swastika to Jim Crow” on February 1 to a full house, as part of a community engagement series supporting its new exhibit “Allied in the Fight: Jews, Blacks and the Struggle for Civil Rights.”

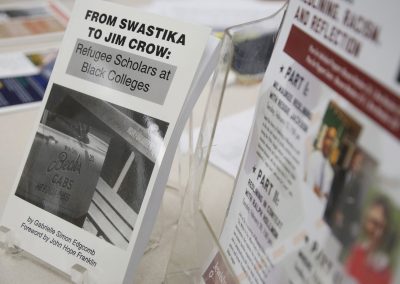

Based on a book by the late author Gabrielle Simon Edgecomb, From Swastika to Jim Crow tells the little-known story of Jewish refugee scholars who escaped Nazi persecution by fleeing to America, and when faced with anti-Semitic sentiment at mainstream American universities, were hired for positions at historically black colleges and universities (HCBUs) in the then-segregated South.

The film became the basis of a traveling exhibition which first premiered at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York, then traveled around the country to a bunch of different African-American and Jewish museums.

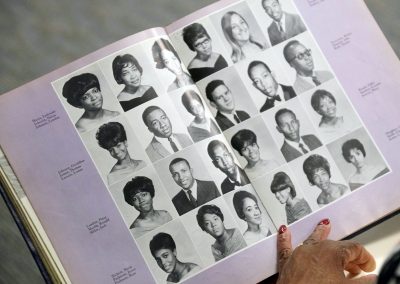

Following the film, Joyce Mallory, an Organization Development Consultant for the Nonprofit Center of Milwaukee and a graduate of Tougaloo College in Mississippi, discussed her experiences with Sociology Professor Ernst Borinski, a German-Jewish sociologist and intellectual who immigrated to the United States from Germany in 1938 and contributed to undermining Jim Crow laws in Mississippi in the 1950s and 1960s.

“I’ve been able to find my way because of the foundation Tougaloo gave me and Dr. Borinski’s belief in us,” said Mallory. “He created opportunities for us to challenge what we knew about what wasn’t right, what wasn’t fair, in a way that helped us be able to shape our lives and have an impact on others.”

Soon after Adolf Hitler took leadership in Germany in January, 1933, the Nazi Party issued laws to ban Jewish scholarship and pedagogy. These restrictive laws had huge support in the ivied walls of academia. According to Dr. Ismar Schorsch, the former Chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary, students were amongst the most rabid of Nazi sympathizers.

By 1940, some 2,000 German and Austrian academics had been dismissed. These members of the intelligentsia, called “mandarins” for their revered status in society, were cast out in a world where few spoke fluent English and fewer probably had manual skills.

Limited assistance came from the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars, founded in New York in 1933, which offered one-year grants to colleges to partially subsidize salaries of the refugees. While the Committee did rescue over 300 scholars from Nazi-run Europe, they were the ones with established reputations such as philosopher Martin Buber, physicist James Franck, and writer Thomas Mann.

The younger and lesser known academics arrived with tourist visas, desperately seeking work on their own. Walter Fales worked as a butler and cook until he landed a position in 1946 as Associate Professor of philosophy at Lincoln University, a traditionally black college in Chester County, Pennsylvania.

Some 50 to 100 of these refugee scholars found haven in these black colleges, where the facilities were ramshackle but where the students had a keen thirst for knowledge. These professors became beloved on their campuses, despite their formal European customs such as insisting that their students wear jacket and tie.

Former students testified on the film to the pivotal role these Jewish mentors had on their lives. John Biggers arrived at Hampton Institute, now University, in Virginia with a work-study scholarship for plumbing, but Professor Viktor Lowenfeld opened his eyes to the world of artistic creativity. Biggers became an artist, professor, and founder of the Art Department at Texas Southern University in Houston.

Civil rights activist and author Joyce Ladner recalled that she could not afford the application fees for graduate school, so her professor at Tougaloo College in Jackson, Mississippi, Ernst Borinski, a former judge and law professor in Germany, paid them with his own money. When she reported the successful defense of her doctoral dissertation four years later, he sent a telegram with his congratulations and $100 for her to celebrate the milestone with her friends. The telegram is in the exhibit.

“While the Jewish professors were not accepted by the whites in Mississippi, they were regarded by the blacks as either non-white or even black,” said Mallory. “One of my classmates firmly believed that because the Jews were mentioned in the Bible, and any people who had suffered as they did in ancient Egypt, they just had to have been black.”

The catalyst for the film came from a letter by Professor Herz to The New York Times about the anti-semitic comments of speakers at Howard University and other black colleges in the late 1990s. He referred to the 1993 book by Gabrielle Edgcomb, From Swastika to Jim Crow: Refugee Scholars at Black Colleges, which inspired the filmmakers to make their documentary.

The program concluded with a talkback session hosted by Dr. Fran Kaplan, who recently retired from her work at America’s Black Holocaust Museum.

- Joyce Mallory: Jewish Refugee Scholars at Black Colleges

- Exhibit details partnership between Jews and Blacks in shared struggle for Civil Rights

- Rosenwald Schools and their legacy of Black-Jewish collaboration for Negro Education

- When Jews were neither white nor black but “some sort of colored folks”

Lee Matz