“Segregation was caused by friction between the colored and white clerks, and not done to injure or humiliate the colored clerks, but to avoid friction. The purpose of these measures was to reduce the friction. It is as far as possible from being a movement against the Negroes. I sincerely believe it to be in their interest.” – President Woodrow Wilson, after ordering federal government offices be segregated during his first term as President

“These THUGS are dishonoring the memory of George Floyd, and I won’t let that happen.” – President Donald Trump, referring to anti-police violence protestors

“Our incredible success in rebuilding America stands in stark contrast to the extremism and destruction and violence of the radical left. We just saw it outside. We just saw it outside, you saw these thugs that came along.” – President Donald Trump, at campaign rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma June 20, 2020

The past century has been one of constant struggles by black people for basic rights white people take for granted. The White House is currently occupied by a man whose policies and statements are similar to his predecessor Woodrow Wilson. Just as Wilson divided the nation after being elected, Trump has lived off the constant rhetoric of division. Calling black people “thugs” publicly is part of the President’s appeal to his base.

Wilson after being elected with overwhelming black support, immediately segregated federal buildings. Restrooms, and cafeterias had WHITES ONLY and COLORED ONLY signs installed throughout the nation’s capital. His administration began to require photos for all job applications, fired blacks for dubious reasons and refused to hire blacks for the types of jobs that allowed black families to prosper in Washington DC.

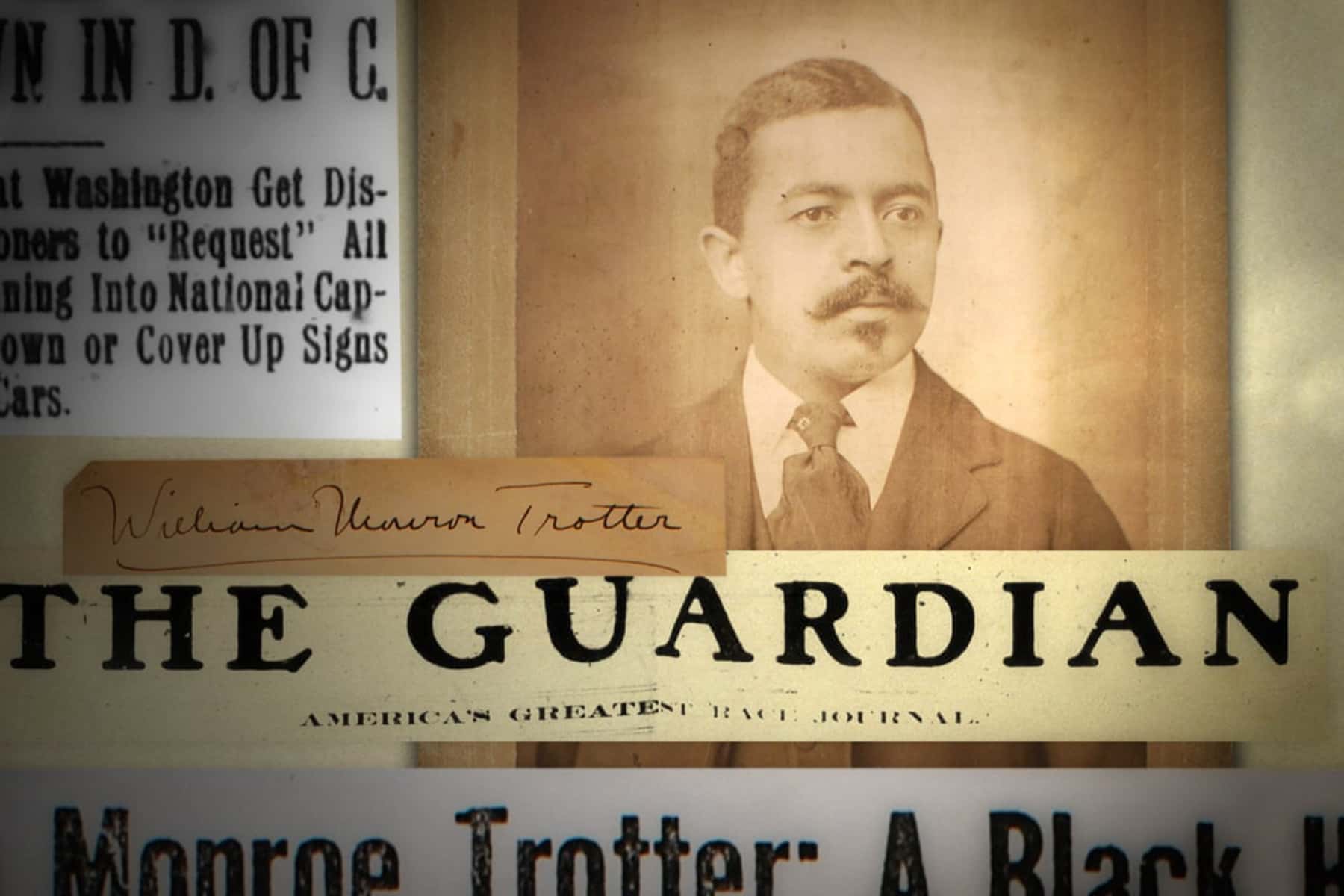

As we are being brutalized by police officers who are supposed to be protecting us, we have every right to protest today. Despite what many may say about the police, we’ve seen multiple viral videos over the past several weeks of police officers brutalizing peaceful protestors. The reality of life in America is that police violence is a recurring theme in black people’s lived experiences. We are not in a “post-racial” America when we still endure the same indignities we saw one hundred years ago when W.E.B. DuBois, William Monroe Trotter, and Marcus Garvey warned us to protect ourselves from American racism by uniting in our efforts.

Trotter, the first black member of the Phi Beta Kappa honor fraternity, graduated Harvard with honors in 1895. He edited his newspaper, The Guardian, which was founded to disseminate “propaganda against discrimination.” He was a strong voice advocating constantly for racial and social justice. Trotter lead non-violent protests against racism in all forms including leading a call to stop screening of the virulently racist 1915 film The Birth of A Nation.

Most of us never learned about Trotter in school because he was too “militant.” He was a founding member of the Niagara Movement which became the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) but left in disgust saying that the newly formed organization was beholden to “white money” and would never speak strongly for the issues and concerns of the black community.

“My vocation has been to wage a crusade against lynching, disenfranchisement, peonage, public segregation, injustice, denial of service in public places for color, in war time and peace.”

Trotter directly challenged the president for permitting the segregation of black and white government clerks in a meeting at the White House asking the president, “Have you a new freedom for White Americans and a new slavery for your Afro-American fellow citizens?” He was thrown out of the White House by an exasperated Wilson. Wilson had received strong support from blacks in winning the presidency in 1912 by promising to support black causes. Wilson got more black votes than any previous Democratic candidate for president.

It did not take long for him to turn his back on those blacks who voted for him. Trotter and other leaders of the NAACP were able to secure two face-to-face meetings with the president. During the second meeting, Wilson lectured Trotter, “Now, what makes it look like discrimination is that the colored people are in the minority.” Trotter told the president that separating segregation from discrimination made no sense. In a testy back and forth lasting nearly an hour, Trotter reminded the president that blacks saw him as a second coming of Abraham Lincoln based on his campaign promises. Wilson exploded “You are the only American citizen that has ever come into this office who has talked to me with a tone. You have spoiled the whole cause for which you came.” Trotter referred to America’s Christian principles, but Wilson quickly cut him off. “I expect those who profess to be Christians to come to me in a Christian spirit.” The president told the delegation of black leaders that if they ever wanted to talk to him again, they would need to find a different spokesman. Trotter was never invited back to the White House again.

Trotter was also a huge critic of Booker T. Washington. While attending elementary school I remember Booker T. Washington being talked about in the same way as Dr. King. I was told he was one of our greatest leaders and spokespersons. Washington’s 1905 Atlanta Compromise speech to a large white audience was seen as a huge step backward by Trotter, DuBois and many other black leaders. He received a standing ovation from the crowd at the conclusion of the speech.

“To those of my race who depend on bettering their condition in a foreign land or who underestimate the importance of cultivating friendly relations with the Southern white man, who is their next-door neighbor, I would say: “Cast down your bucket where you are”— cast it down in making friends in every manly way of the people of all races by whom we are surrounded…it is in the South that the Negro is given a man’s chance in the commercial world, and in nothing is this Exposition more eloquent than in emphasizing this chance. Our greatest danger is that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labour, and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life… It is at the bottom of life we must begin, and not at the top. Nor should we permit our grievances to overshadow our opportunities…As we have proved our loyalty to you in the past, in nursing your children, watching by the sick-bed of your mothers and fathers, and often following them with tear-dimmed eyes to their graves, so in the future, in our humble way, we shall stand by you with a devotion that no foreigner can approach, ready to lay down our lives, if need be, in defense of yours…In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress…The wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremest folly, and that progress in the enjoyment of all the privileges that will come to us must be the result of severe and constant struggle rather than of artificial forcing.”

Washington was immediately attacked by progressive black leaders and newspapers around the country. Trotter complained about Washington’s Tuskegee machine as a tool to strangle “colored dissent.” Trotter’s discontent led him to start his own paper which he described in a letter to his former college roommate John Fairlie.

“I have at last become so washed down and alarmed by the growth of caste feeling and caste laws, and so angered at Booker Washington’s betrayal of colored people and so indignant at the Boston Herald and Transcript for smothering all those who wished to condemn him that I have founded a newspaper of my own in partnership with a friend named Forbes. I can now feel that I am doing my duty and trying to show the light to those in darkness and to keep them from at least being duped into helping in their own enslavement.”

Trotter saw his newspaper as a vehicle to “hold a mirror up to nature.” Trotter and DuBois were leaders during a tumultuous time when blacks were not only living under the yoke of Jim Crow they were being murdered by mobs of whites across the country. In 1906 whites in Atlanta, resentful of the wealth of industrious blacks running their own businesses, on September 22 began rampaging through Atlanta’s downtown streets rioting for three days. As many as 40 blacks were killed by the mobs. This riot was the catalyst for the founding of the NAACP three years later.

Two years later August 14 to 16 Springfield, Illinois, the home of Abraham Lincoln, saw a massive white-led riot against the black community. The mob attempted to lynch two black men, Joe James and George Richardson who had been arrested. The sheriff sent the two to a safer location so the mob instead lynched substitute victims Scott Burton and William Donegan. The mob attacked blacks in the city and outlining communities. According to blackpast.org, “Mob leaders carefully directed the participants to destroy only homes and businesses either owned by blacks or which served black patrons, thus leaving nearby white homes and businesses untouched.” Over 2,000 blacks were expelled from the city. As many as 5,000 white Springfield residents took part in the rioting. Illinois Periodicals recounted the riot in an article written by Robert Senechal.

The rioters — minus most of the spectators — next methodically destroyed a small black business district downtown, breaking windows and doors, stealing or destroying merchandise, and wrecking furniture and equipment. The mob’s third and last effort that night was to destroy a nearby poor black neighborhood called the Badlands. Most blacks had fled the city, but as the mob swept through the area, they captured and lynched a black barber, Scott Burton, who had stayed behind to protect his home.

From July 1 through July 3, 1917 a white mob rioted in East St. Louis, Illinois, just across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, Missouri. At least 39 blacks and as many as perhaps 100 were killed by the mob of whites angry that blacks demanded fair wages. The St. Louis Post Dispatched described the carnage. “Rampaging white men used guns, rocks, pipes and nooses. White women egged them on, sometimes taking part. Rioters set fires in black neighborhoods and torched the Broadway Opera House on the false tale that blacks were hiding there. Many fled to St. Louis across the Eads and Municipal (MacArthur) bridges. East St. Louis police stood by or joined the carnage. Illinois National Guard soldiers who were hustled to town did little to protect people until late in the day.” More than 300 black homes and businesses were burned.

This violence against blacks during WWI would accelerate during the spring after WWI ended. During the first six month of 1919 seven black veterans in uniform were tortured and lynched by white mobs across the country. My great-grandfather was threatened with death by whites in my hometown if he was caught wearing his uniform after serving two years in the Army in Europe during WWI.

The summer of 1919 is known as Red Summer because of the dozens of white-led riots across the country. Cameron McWhirter’s book Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America is the definitive work on the riots which actually began in the spring of 1919. Black veterans coming back from WWI demanded and expected to see a dismantling of Jim Crow segregation.

“The euphoria of victory evaporated to be replaced by the worst spate of antiblack violence; labeled the Red Summer, the riots and lynchings would last from April to November 1919, claiming hundreds of lives, and leave thousands homeless. Blood — mostly blacks’ — flowed across America from Connecticut to California, Texas to Nebraska. At least twenty-seven major riots and mob actions immobilized the nation’s capital and small cities large and small, including Chicago, Omaha, Knoxville, Charleston, and the Delta town of Elaine, Arkansas… blacks fought back; picking up any weapon that was at hand, their retaliation against armed mobs was swift. It was the first stirrings of the civil rights movement that would change America forever.”

These riots were followed by the Tulsa Race Massacre in 1921 and the Rosewood Race Massacre in 1923. Dr. Geoff Ward of Washington University in St. Louis has documented the history of racial violence in America by creating the Racial Violence Archive. “There is growing awareness of the lasting significance of historical racial violence in the United States and increasing effort toward redress. Area histories of enslavement, lynching, and other racial terror and dispossession relate to inequality, conflict, and violence in the same places today. These ‘haunting legacies’ include heart disease and other health disparity, black victim homicide, white supremacist mobilization, and corporal punishment in schools.”

“The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.” – Ida B. Wells

We are emboldened by the protests around the world after the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor to fight for a completion of an unfinished civil rights movement. We are fighting the same battles from 100 plus years ago in this country. The events alliterated in this article have been hidden from most Americans. We don’t know what we don’t know. As a result whites are pushing back against the current demands in the same way they did in the 1950s and 60s. Until you are able to understand that this isn’t about police brutality and long ago slavery or simple Jim Crow signs—that it is about long term discrimination and blatant racism, intentional patronizing by narcissistic elected officials and their acolytes who embolden their power plays—the battle will never be over.

In Brazilian philosopher Paulo Freire’s 1970 classic, The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, he speaks about humanization. “It is thwarted by injustice, exploitation, oppression, and the violence of oppressors; it is affirmed by the yearning of the oppressed for freedom and justice, and by their struggle to recover their lost humanity.”

“WE WANT FREEDOM. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community. We believe black people will not be free until we are able to determine our own destiny…We want decent housing, fit for shelter of human beings…we want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of black people.” – 1966 Black Panther Party for Self-Defense Party Platform and Program

“It is solely by risking life that freedom is obtained,…the individual who has not staked his or her life may, no doubt, be recognized as a Person; but he or she has not attained the truth of this recognition as an independent self-consciousness.” – Georg Hegel, The Phenomenology of Mind, 1967

© Photo

Northern Lights Production