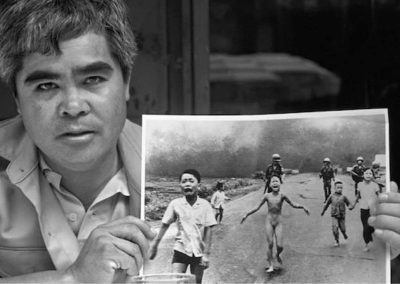

One of the most unforgettable images from the Vietnam War was of a little girl running naked, after surviving an accidental napalm attack on the village of Trảng Bàng. The composition of the Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph “The Terror of War,” taken by Vietnamese photographer Nick Ut, captured the shattered innocence and tragedy of the American conflict there.

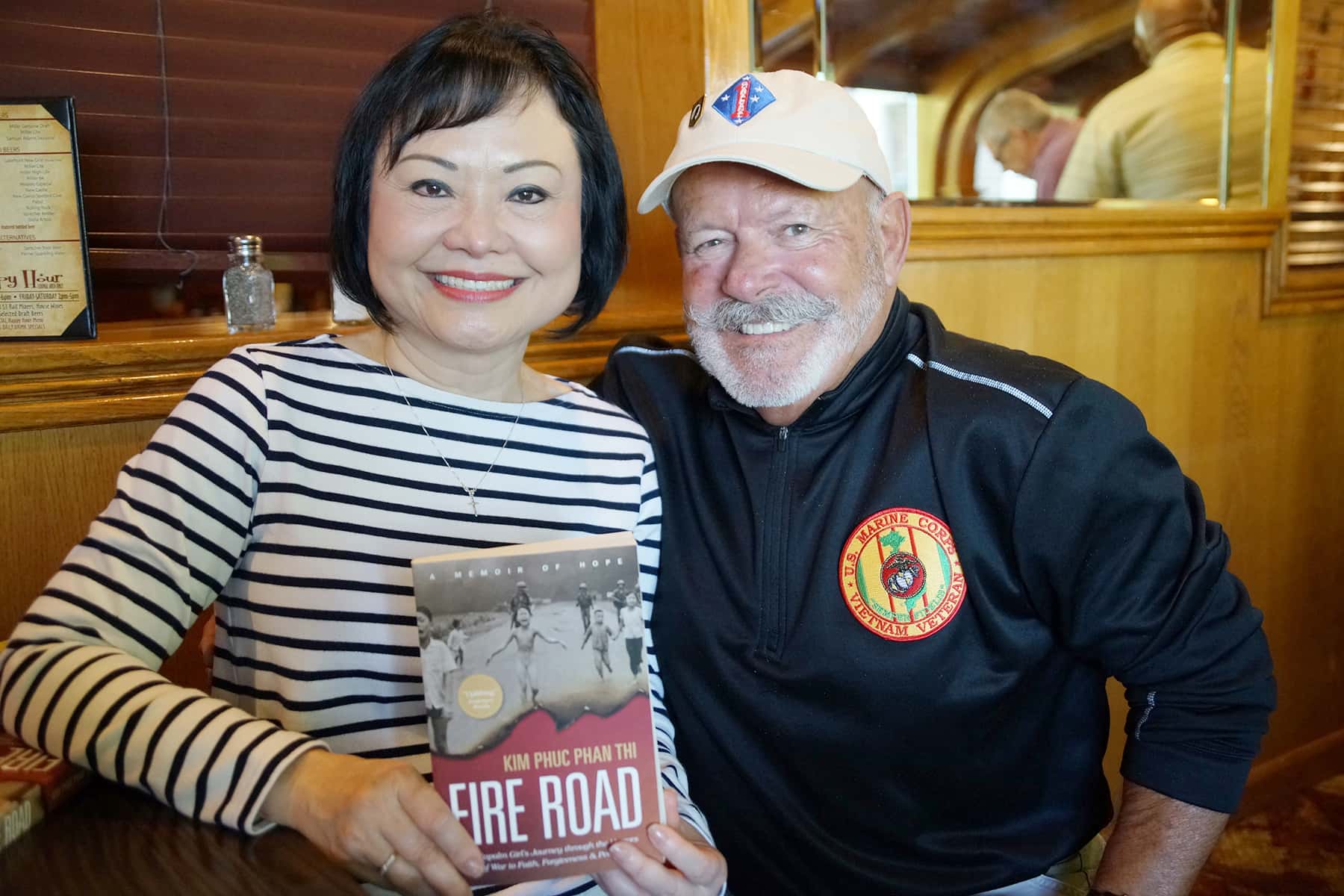

No longer that 9-year-old little girl, Phan Thị Kim Phúc commemorated the 47th anniversary of that bombing during a visit in Wisconsin on June 8, with a powerful message of hope. Known as the “Napalm Girl,” Kim Phúc still carries the physical and emotional scars from that day in 1972.

“In history, there have always been stories of resistance and fighting back. But now, my weapon is love and forgiveness,” said Phúc. “It all comes from that little girl in the napalm photo, and her life in Vietnam means a lot to me.”

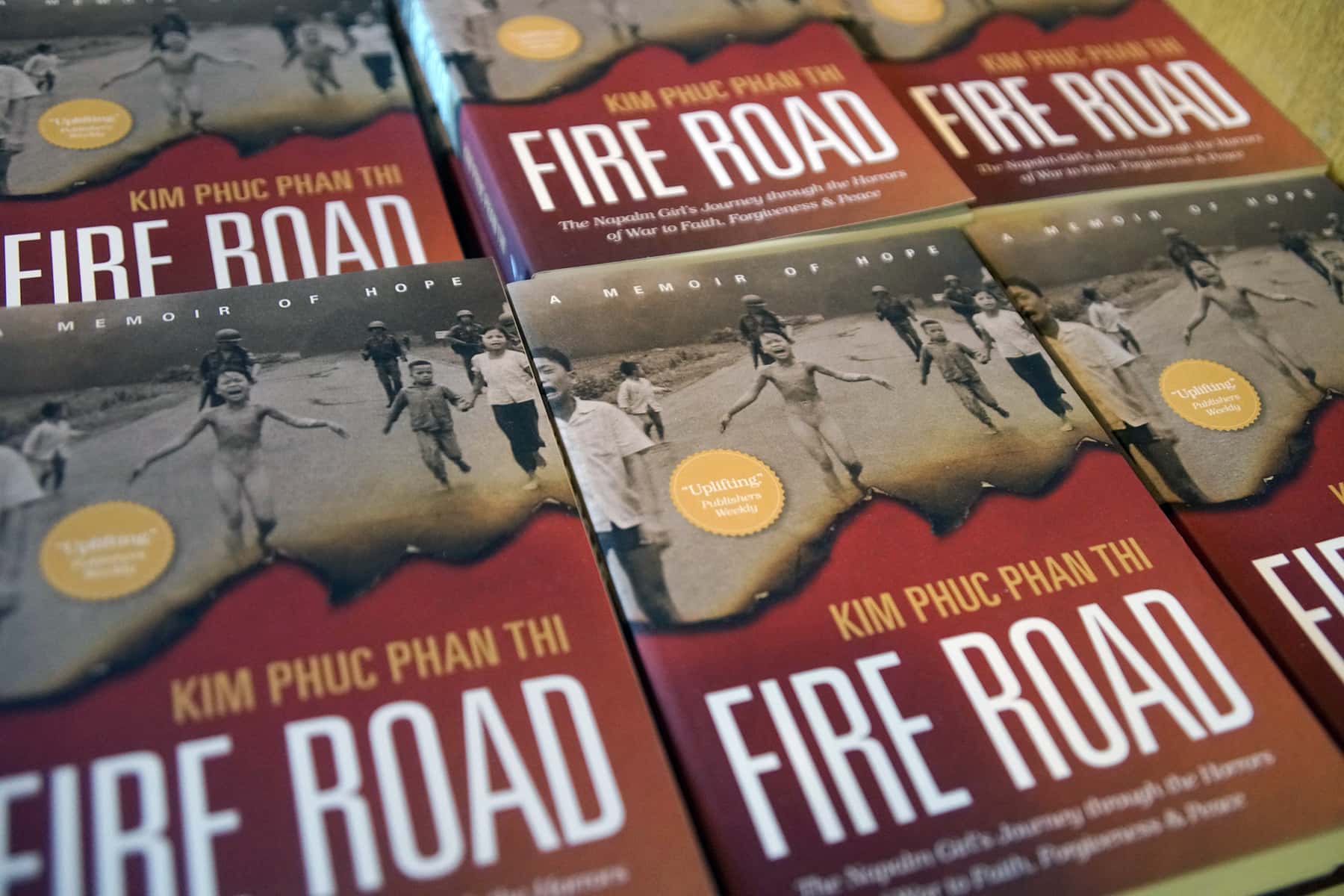

Phúc traveled from her home in Canada to several cities across Wisconsin, giving keynote presentations and signing copies of her 2017 book Fire Road: The Napalm Girl’s Journey through the Horrors of War to Faith, Forgiveness and Peace.

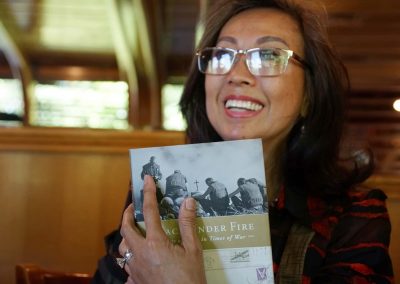

Nick Ut, the Associated Press photographer who captured the iconic war image of her pain and desperation, joined Phúc for her visit to Madison. The events were designed to help raise funds to build a Peace Library in the Vietnamese province where she was born and raised. Children’s Library International has more than such 30 libraries in Vietnam and Cambodia, and number 35 will be in Trảng Bàng, 30 minutes north of what was then Saigon.

Chuck Theusch, a Wisconsin native and veteran who served in Vietnam from 1969-70, started the foundation in 1999 after his first return trip to the country. He had originally only intended to sponsor an orphan, like other veterans were doing at the time.

“I met with the Communist Party officials in the district where I had fought, and after many beers – and a great translator – I came up with the idea for something bigger,” said Theusch. “I wanted to build a library, and I was thinking about getting books and stuff like that as a resource for the community. Free libraries have always been big for us here in America, going back to the days of Carnegie.“

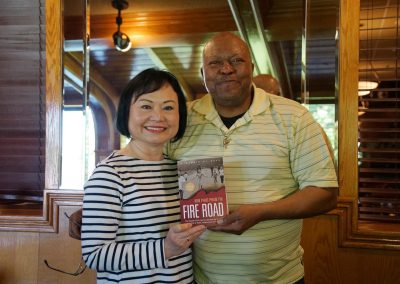

When he came back to Wisconsin from that visit to Vietnam, Theusch did not find any financial support for his idea. So he funded the construction of the first Peace Library himself. He attributed some of the early success with the project as being pure luck, by picking a good contractor to produce his vision. Through Theusch’s friendship with Milwaukee veteran Joe F. Campbell, who knew Phúc from his own connection to Trảng Bàng during the war, the special library project was able to move forward.

“Kim has her own foundation for healing children of the war,” said Theusch. “But we’re working together for this, because she’s never been able to build anything in Vietnam due to the political sensitivities. So she’s flying under our wing to build this library for future generations in her village, but also for the memory of her two cousins that were killed that day.”

The impact of the libraries has been good for the Vietnamese children, but even greater on the relationships between the Vietnamese and Americans. In the late 1970s, the Vietnamese government used Phúc for many years as a poster child of the terrible things the United States did in the war. She was supervised daily and subjected to endless interviews by the Vietnamese government, with communist officials summoning her to Ho Chi Minh City, formerly Saigon, to be used in propaganda films.

While studying at Havana University she met Bui Huy Toan, a fellow student from Vietnam and they were married in 1992. The couple traveled to Moscow, Russia, for their honeymoon. It gave them a rare opportunity to flee to Canada when the plane stopped in Gander, Newfoundland for refueling. But after seeking asylum, Phúc was cut off from her family and not allowed to return to Trảng Bàng.

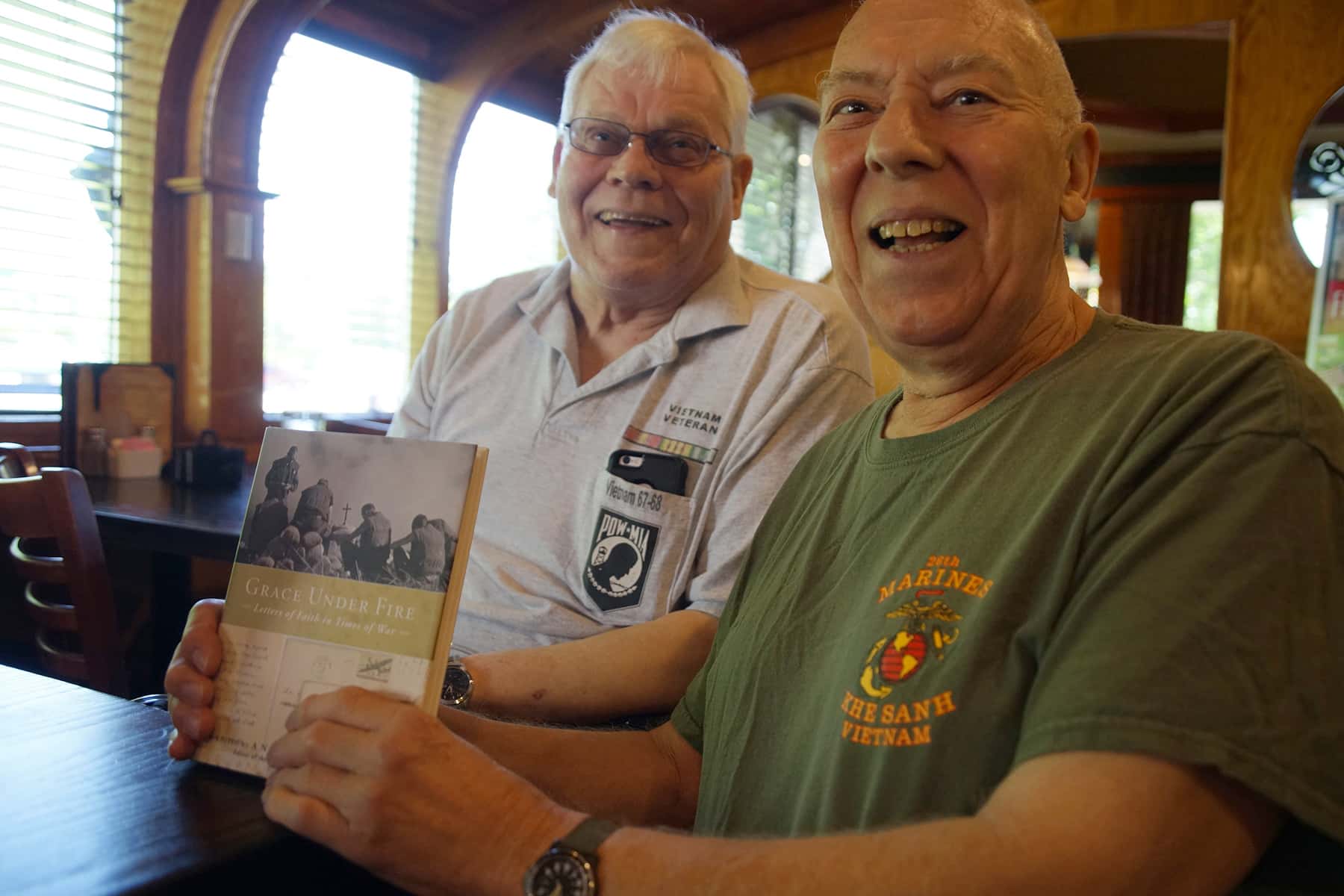

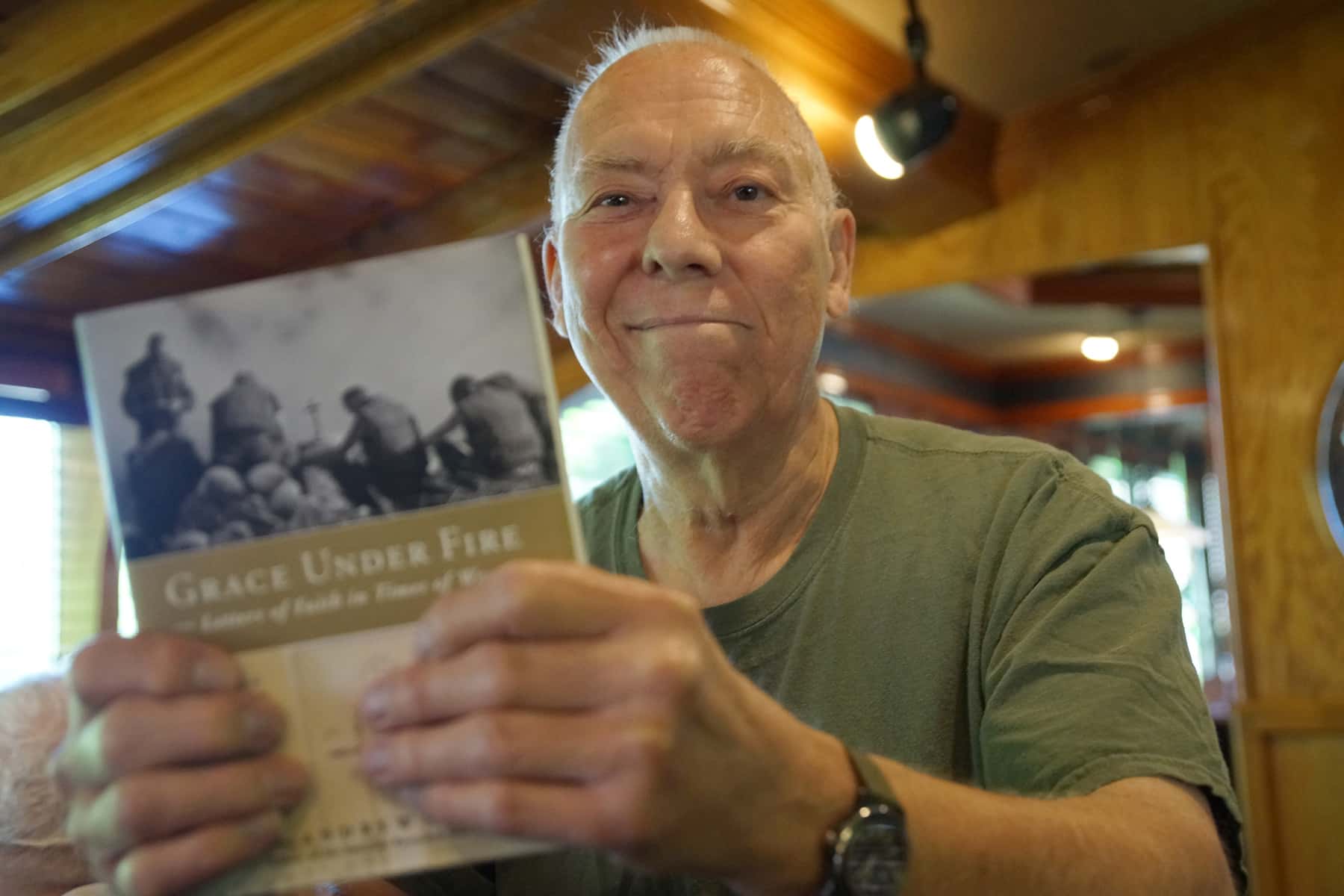

Before returning to Canada on June 10, Phúc visited Milwaukee for a private lunch with a dozen local veterans who all served in Vietnam, and several who had spent time in the area where she lived. She talked candidly with the group about her emotional experience as a victim of war, and how she had lost hope after suffering from the napalm burns. As a devout Buddhist, she said she became angry and hateful and lost the enthusiasm to live.

Then in 1982, she discovered a Bible in a Saigon library and began reading it as she tried to make sense of what God meant in her life. That began her journey forward along the road of forgiveness, as she embraced Christianity and found a renewed purpose for her life. When Phúc and Theusch connected, she knew that her faith had been rewarded.

“The list of my enemies became my prayer list. And through my faith, I came to believe that peace, love, and forgiveness will always be more powerful than bombs,” said Phúc. “When hatred is used to fight evil, everyone suffers. But when love is used to fight evil, love wins. So for all the people who did wrong, we need to pray for them. We need to love them, and love each other, just as God loves us.”

Trảng Bàng was positioned between Saigon and Phnom Penh along Route 1, a strategic supply road during the war. On June 8, 1972, a South Vietnamese plane accidentally dropped its load of napalm, a type of incendiary bomb consisting of a highly flammable jelly-like petrochemical that sticks to the skin as it burns, on South Vietnamese troops and civilians. Nick Ut was a photographer for the Associated Press when he saw a terrified girl run towards him. She had ripped off her burning clothes while fleeing the devastation of her village.

The photo of Phúc was unprecedented for the Associated Press because of its full frontal nudity. An editor for AP had originally rejected it, but Pulitzer Prize photo editor Horst Faas overrode any reservations and transmitted the image to news services around the world. Phúc became one of the most visible victims of the war, but she did not actually see the photo for more than year later.

Phúc spent 14 months in hospitals, undergoing 17 skin grafts and surgeries that left her in constant pain for years. Her photograph was an enduring icon of the Vietnam war, and it kept a human face on history while memories faded. In time, that little girl was able to disappear from public view. But a decade later, the news media revived an interest in Phúc which brought her unwanted attention. After seeking asylum in Canada and beginning her own family, she thought she could finally escape from the picture.

But in 1995, another journalist tracked her down and Phúc’s peaceful and anonymous life was again front page news. To Phúc, it felt like the picture of that little girl would not let her go. But through her faith, she transformed from an unwilling victim and used her position to advocate for peace. She took control of the narrative about her photograph, and established the Kim Foundation International, which provides medical and psychological assistance to child victims of war.

The idea came as a result of her meeting veterans in Washington DC involved with the Vietnam War Memorial. The foundation became a way for Phúc to give something back in return for all the help she had received. It also provided a means for her to promote peace and forgiveness.

That message was strongly shared during her stop in Milwaukee, among Vietnam veterans like Joe Campbell and Chuck Theusch, former 101st Airborne medic George Banda, former Marine Bob Pfeifer, and former Navy Chaplain and survivor of the Siege of Khe Sanh, Ray W. Stubbe.

“Faith is what helped me learn how to move on, and rediscover joy in my life. I had to let go of my suffering since I was that 9 year old girl and forgive those who caused it.” Phúc added. “So, now my focus is on those children who were like me. I can use my life to give them hope. I am still alive, so I have to use my voice to speak for them, and all those who can’t. Children are suffering right now, and I want them to know, never give up.”

- Inconvenient Images: How pictures teach us to see the world for what it is

- Milwaukee’s hometown Air Wing kicks off Armed Forces Week with aerial refueling flight

- William Pelkofer: Wisconsin Air National Guardsman takes home-grown path for pilot training

- Dawn of the Red Arrow: Documentary details birth of Wisconsin’s 32nd Division in World War I

- Bay View students revive Lance P. Sijan Memorial Scholarship as example of leadership, love, and honor

- Brewers legend Robin Yount recognized for years of citizen involvement in helping the Armed Forces

- Gold star family, George Banda, and Iwo Jima veterans recognized with Sijan award for valor

- Veterans Day Parade 2018 honors Milwaukee’s Red Arrow Division for its WWI service

- Milwaukee Notebook: Red Arrow, the Park that Moved

- Janine Sijan Rozina: A story not of war but the spirit of love

- “Sijan” and Chip Duncan’s “The First Patient” among world premieres at Milwaukee Film Festival

- Fellow POWs honor their fallen brother at Sijan Plaza dedication

- Photo Essay: Preview of Sijan Plaza and memorials of honor

- Photo Essay: An example of courage installed at Mitchell Airport

- Ben Domian: a life influenced by family and Lance Sijan

- Vietnam combat medic George Banda honored at tribute to Latino veterans

- Lynn Novick: A discussion about her Vietnam War film on Veterans Day

- The irony of visiting heroes at Arlington, the former home of a national traitor

- Photo Essay: Seeing the Nation’s Capital with Milwaukee Eyes

- George Banda: Honoring lost friends in vigil to Vietnam veterans at The Wall

- Maya Lin: Ceremony marks 35th anniversary of Vietnam Memorial’s healing power

- George Banda: The Humble Hero

- Audio: An American story from Mexico to Vietnam

- Purple Heart Day honors Milwaukee’s wounded veterans

- Photo Essay: Milwaukee’s 54th Annual Veterans Day Parade salutes hometown heroes

- Online patriots too lazy to honor troops by actually attending Veterans Day Parade

- Thank You, Canada, for loving Milwaukee Veterans

- Aerial demonstration squadrons announced for 2019 Air & Water Show

- Flying with the Golden Knights during the Milwaukee Air & Water Show

- Air & Water Show 2018 performances prepared and waited for weather to clear

- Exclusive: 360° view of skydive at 2,000 feet over Milwaukee with precision landing

- Video: Army’s elite parachute demonstration team descends over lakefront

- Airshow sees Army Parachute Team descend through the atmosphere

- Photo Essay: Golden Knights Practice Jump attempt at 2,000 feet

- Photo Essay: Golden Knights Precision Landing from 12,500 feet

- Photo Essay: Free-falling with the Golden Knights Demonstration Team

- Video: U.S. Army Golden Knights parachute into Milwaukee Airshow

Lee Matz, Nick Ut, and Joe F. Campbell