Over the past several years, Milwaukee Independent has used its editorial platform to push for public recognition of George Marshall Clark, and to memorialize the tragedy of his death. In this essay, guest writer Tyrone MackLee Randle Jr. shares his personal story and connection to the subject. He will continue to educate and inform the community as the situation develops.

A curated selection of our published news articles about Clark and the subject of lynchings can be found at: http://mkeind.com/georgemarshallclark

“Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.” – James Baldwin

How about we start with facing the problem of historical disinformation, because what is being taught seems to exclude certain narratives, purposefully. As a youth, I remember learning that racism was a “Southern” thing. Milwaukee’s failing school system taught me that after 1964, racism had ended due to the Civil Rights Act.

I remember being confused about my Blackness for so long. This sense of loss of identity is partial because Black youth are not taught how to comprehend the information given to us. Especially when it is regarding Black History – which is not separate from America’s History.

I could have easily become the male Candice Owens. Being taught by both private Lutheran school and Milwaukee public school teachers, who were 80% White, could not have helped my still-developing sense of self.

I had not done much research since my college days, but I found myself almost compelled to dig up historical narratives that deserve a place within American history books. I felt that many of these narratives, whether they portray the successes or the struggles of the African American people, are essential to the building of the Black identity – for both youth and adults.

“To win people for Christ. It is necessary to Europeanize them. Behind all systems of administration lies the fundamental question of what we intend to make of the African. The question has, whether in explicit terms or not, been answered in several ways …

One possible and largely practiced policy is that of repression which means keeping the native [Afrikan] in a subjected and inferior position, (keep him in his own place) as a mere serf [slave] of the dominant race …

The first method begins by destroying the institution, religions, and habits of the people and superimpose upon the ruins whatever the governing power considers to be a better administration system …

The other method – while checking the worst abuses – tries to graft our higher civilization on the soundly rooted native stock, bringing out the best of the what is in the native tradition and molding it into a form constant with our modern ideas and higher standards.”

– Edwin Smith, “The Golden Stool”

On May 25, the world was thrown into chaos after a viral video of the killing of George Floyd hit the internet. Like millions of other people, I felt a rage that was fueled by 400 years of lynching, whippings, and shootings. Many people took to the streets and began marching, demanding that justice be served to the cops involved in his death.

I was one of those Milwaukee citizens, and after 6 or 7 days of marching consecutively, I was hit by a protester’s car while being apprehended by officers of the Milwaukee Police Department.

My incident happened during the early hours of June 4. We were outside of the 5th District Police Station on MLK Drive and Locust Street. After a long day, officers looked to disperse the crowd by charging and assaulting protesters. Multiple officers bounced me between their riot shields, as if I were the puck in a game of air hockey.

After knocking me into a minivan, I fell to the pavement and struggled as the officers attempted to apprehend me. While being held on the ground, a car broke through what seemed like a vast sea of law enforcement officers around me. All that I was able to see, with a knee in my back and my chin to the ground, was the shine of the headlights and legs parting their beams, as multiple officers scurried to safety.

I curled up before the impact, but I was unfortunately dragged by the car for several feet. Since the incident I have been recovering, having suffered three broken ribs and three fractures to my pelvic bone. I would not have even been protesting if my rights as an American citizen, my rights as a human, were not being violated. I also do not believe that war-ready and militarized MPD with National Guard troops were necessary.

For the first few months after the accident I was unable to walk. It was difficult because I wanted so badly to be out in the streets, doing the good work. One day I was thinking about the murder of George Floyd, and my thoughts went down a rabbit hole. I remembered reading an article on Milwaukee Independent about the lynching of a 22 year-old Milwaukee man who had been wrongfully accused of a crime. The man’s name was George Marshall Clark.

“There is no justice in a lynching.” – Kamila Ahmed

Since protest marching was a no-go, my partner Savannha Pyatt (Aadaya Wynter) and I decided that we wanted to plan a simple memorial march in Clark’s honor. Our initial reasoning for wanting to host the march was because some of the text, written about Clark’s story, spoke about there being only one police officer on duty the night he was lynched.

For me and my colleagues (Savannha Pyatt and Kamila Ahmed), this meant that the Milwaukee Police Department had off duty officers within the mob. That would make Clark’s story one of the oldest police brutality narratives within the State of Wisconsin – that had been documented. I felt the need to pay my respects to Clark before we proceeded with the planning of the march.

“ Where there is no closure there is no peace, where there is no justice there is no peace.” – Kamila Ahmed

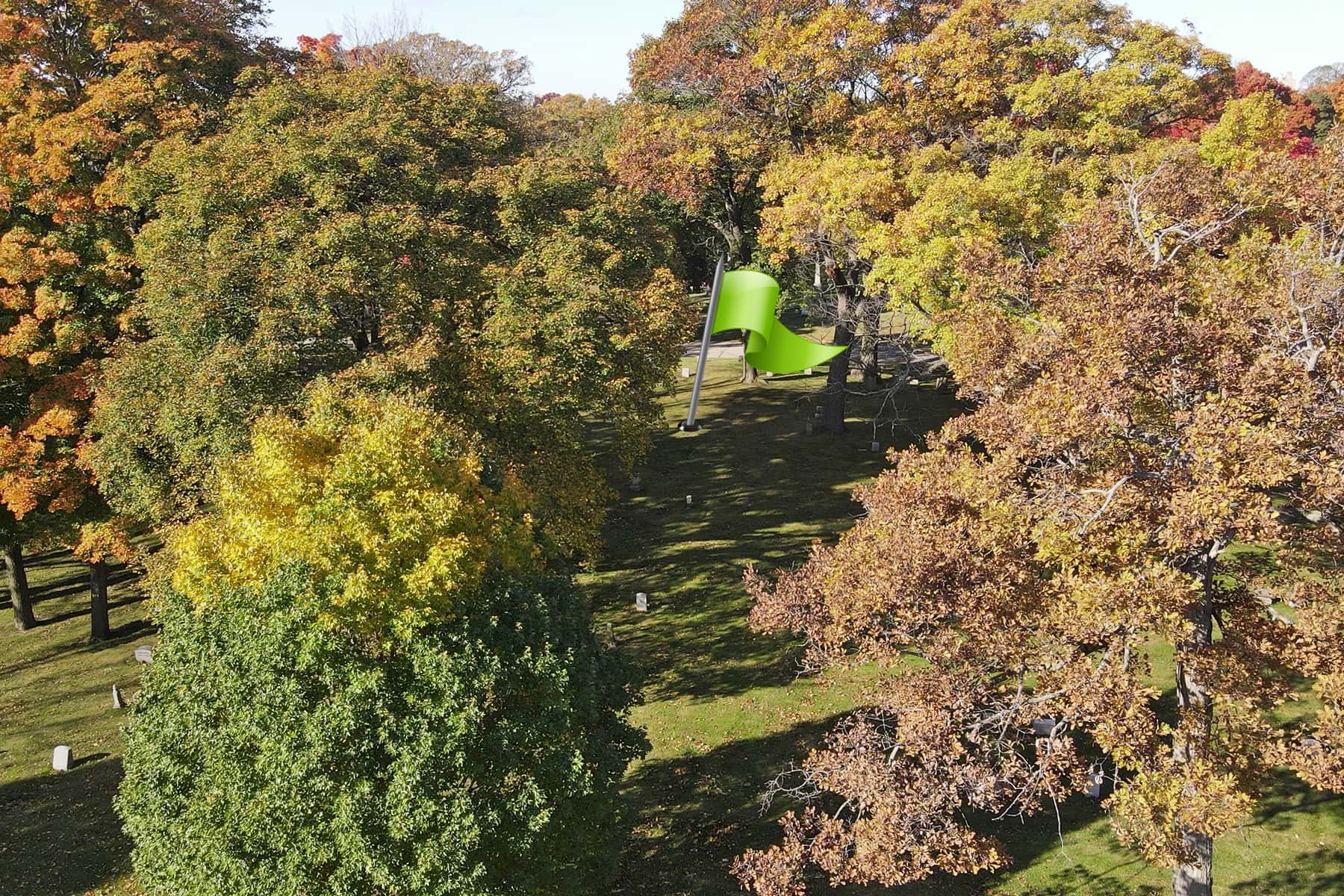

I admit that locating the coordinates to his burial plot took a while, and even America’s Black Holocaust Museum – founded by a lynching survivor – had limited information. But with persistence, Savannha (Aadaya) eventually hit a lead and we were able to obtain his grave information, along with the news that Forest Home Cemetery was where we would find his resting place. The first day, we spent hours brushing off headstones and attempting to transfer barely visible engravings onto paper so that we could distinguish names and dates – but to no avail.

The next day we came back. I had the chance to talk with a gentleman who worked in the Cemetery’s office. His documents showed that Clark was indeed buried in the cemetery, but his grave was unmarked. I then asked him for a list of names that would be surrounding Clark’s grave. He was interested in what we were researching. We were nervous about sharing Clark’s story with him because in Wisconsin it is hard to predict when racism may show its horns. Contrary to our paranoia, he felt moved to help us even more.

He came out to search with us, walking foot over foot, as a tool of measurement to locate the plot. He also shared with us that the section Clark was buried in was owed by the church, but noted that many of the graves surrounding him were of orphans, whose graves are also unmarked.

“Through googling and a lot of web surfing, I found George Marshall Clark’s name on Findagrave.com. There, he is listed plainly, “unmarried; cause of death: murdered.” It even listed his plot information. This was, unknowingly, the start of our mission to find Marshall, and to get him as much recognition as possible, and with hopes that he will be at peace.” – Aadaya Wynter

Since the discovery of Clark’s unmarked grave, we have organized marches to educate both protesters, and those who frequent the areas of downtown Milwaukee that are connected to the day of Clark’s lynching. We had a lot of help from Kamila Ahmed, she is a powerhouse, and a great organizer. She helped a lot with the formatting and structure of the marches, and was a leader in their fulfillment. She also did a great deal of work to promote the event, such as generating a petition.

“The fascination White America has with viewing the torture of black and brown lives never ended, it’s only evolved. Now, spectating racially stemmed murders are more accessible than ever. Instead of having to travel to the location of the murder, people can watch from wherever they are, and they can continue to rewatch, share, and save these events. Without ever having to feel the guilt, of having the actual blood on them. There is a continued lack of accountability, at the fault of the American people. Marshall’s story shows the start of these crimes in this city, and if compared to recent crimes, the data can show how racially biased crimes have evolved since. That is why Marshall’s story needs to be told.” – Aadaya Wyntyer

We feel that the tragedy of Clark’s story is important to the history of the Northern States during the Civil War. This narrative is an important piece of Milwaukee’s history, especially since Clark’s death happened four years before the Civil War ended.

Also, Milwaukee was founded in 1846 and his murder occurred only 15 years after that in 1861, several months after the Civil War began. Clark was held in Milwaukee’s first Courthouse, which was the same courthouse that Joshua Glover escaped 7 years prior. It has been theorized that Clark’s murder was a sort of community retaliation, as a result of Glover being broken out of jail by the local abolitionist.

Clark remains buried in what is arguably the oldest integrated cemetery in Wisconsin – Forest Home, which was established by members of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in 1850. His final resting place has gone unmarked for 159 years. For me, and others, it has become our mission to see a marker installed at his grave site so that our generation, and those in the future, can memorialize him with visits. To keep his story alive is important to Milwaukee’s Black community, and serves as a catalyst for the healing and work still ahead.

“We are simply passing through history. This… This is history.” – Dr. René Belloq, “Raiders of the Lost Ark” (1981)

EDITOR’S NOTE: Forest Home Cemetery used its historic map blueprints and location technology to identify George Marshall Clark’s exact burial plot. Anyone interested in supporting his memorial headstone project can do so through the GoFundMe account, or as a tax-deductible charitable contribution on Forest Home Cemetery’s monument preservation and restoration donation page.