DISCLAIMER: April Fools' Day Parody Special

Editor’s Note: This article is our first attempt to create a fictional “mockunentary” in the parody tradition of April Fools’ Day. The “spoof” idea evolved from a joke about the Milwaukee County Historical Society’s collection of miniature Milwaukee buildings, and a shared childhood fantasy of wearing a monster suit to stomp on such a collection. As Milwaukee enters the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic, our editorial staff felt at least one attempt for a humorous story was worth the try.

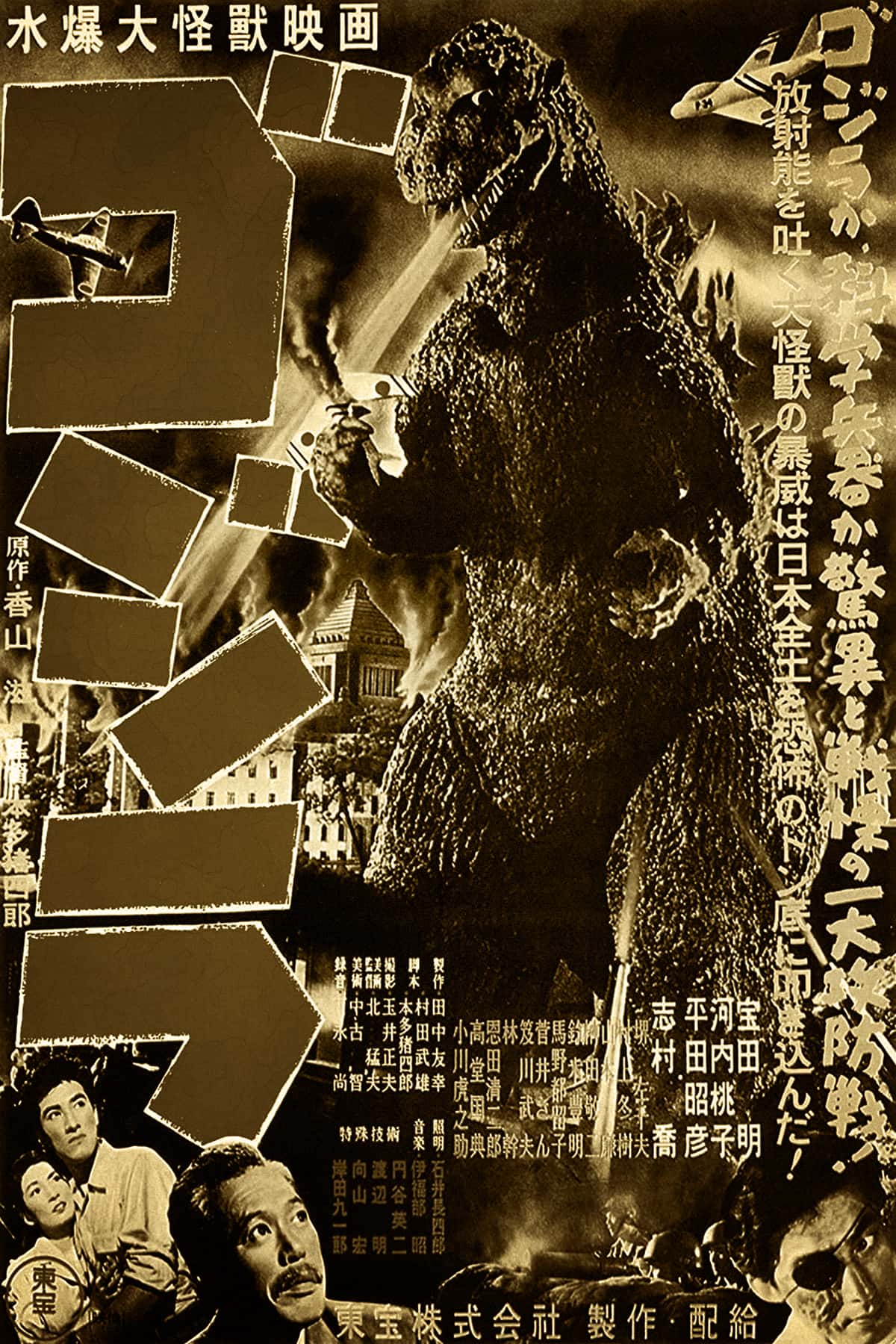

Local historian Nathan Shelby recently released a recreated series of lost promotional stills that had been originally used to pitch Toho Studios on producing the 1956 film “Godzilla in Milwaukee” (ミルウォーキーでゴジラいます).

Japanese filmmaker Tomoyuki Tanaka enlisted Milwaukee native Hernando Mueller to build small scale replicas of the area’s historic architecture. It was an unorthodox concept at the time, to help visualize a plan for bringing Japan’s original “kaiju” to the industrial manufacturing city.

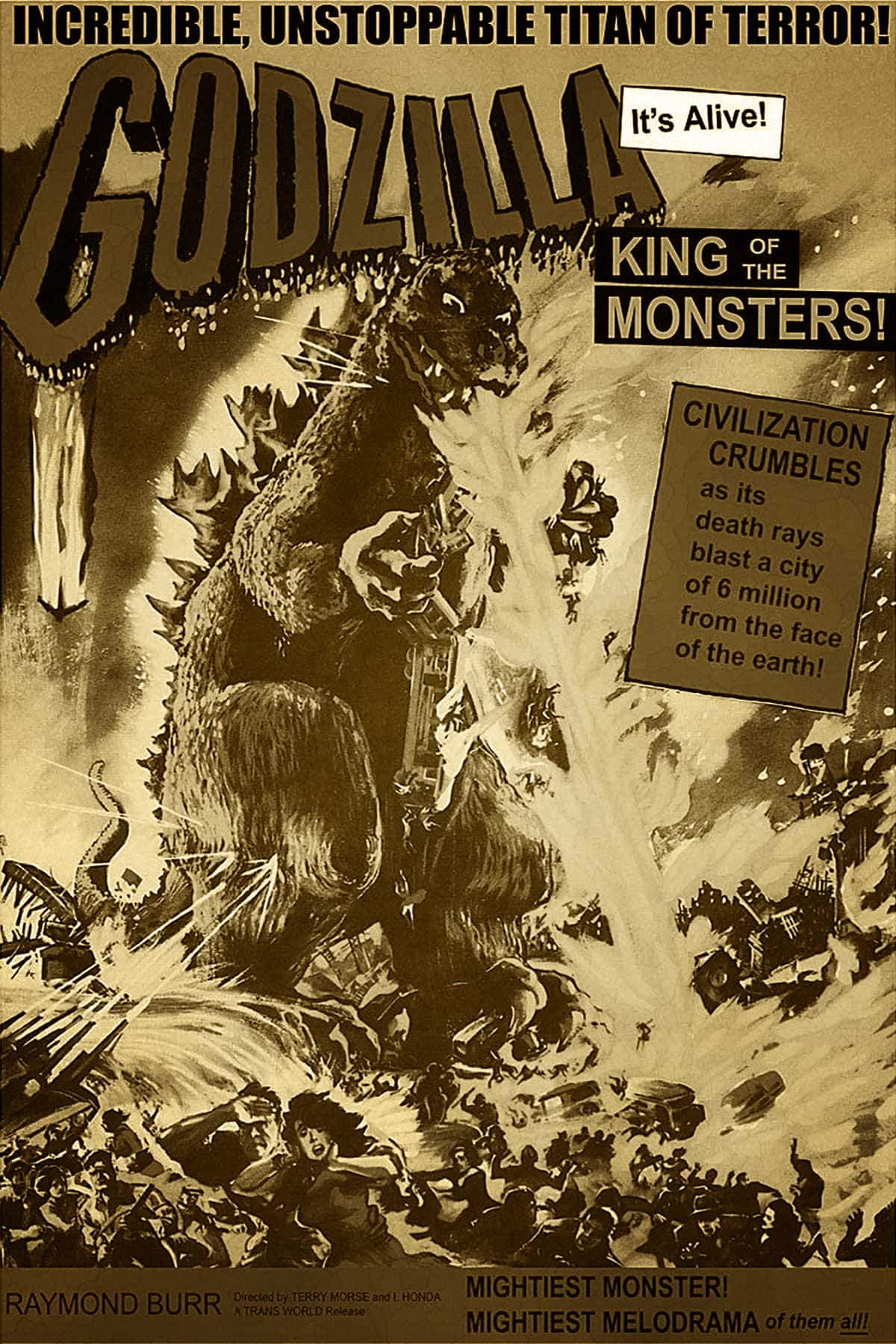

“A North American version of the movie “Godzilla Raids Again” (ゴジラの逆襲) began development in 1955,” said Shelby. “Producer Peter Schreibman planned to take footage from the original Japanese motion picture and film new scenes with English-speaking actors. Schreibman settled on Milwaukee because of its industrial history and recognition as the ‘brew city.’ The Lake Michigan location also offered a plot explanation that linked events in Tokyo via water.”

Filmmakers felt that transferring the original film’s setting would better appeal to an American audience. The remaining Japanese dialog would be dubbed into English. Also in 1954, AJAX Nike Missiles were installed at sites in and around Milwaukee. The established military deployment supported Schreibman’s idea of using atomic rockets against Godzilla as the kaiju emerged from Lake Michigan and rampaged directly into downtown.

“Milwaukee’s manufacturing base and industrial infrastructure had converted to war production in the early 1940s, and was responsible for significant output for the war effort,” said Shelby. “Milwaukee had been contributing weapons and machines to the national stockpile even before the United States entered the war. So it was reasonable to expect that the city could defend against an attack.”

In the original film, Godzilla symbolized a nuclear holocaust from Japan’s perspective. By centering the American version in Milwaukee, the altered storyline played into the growing fears of a military strike by a nuclear armed Soviet Union.

“Godzilla’s Tokyo rampage was designed by Ishirō Honda to mirror the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A similar scenario was planned along the shores of Lake Michigan, foreshadowing an amphibious invasion by Russian troops,” said Shelby.

Mueller had retired in early 1955, and was initially commissioned later that year by Tanaka to meticulously create 16 scale model buildings of Milwaukee landmarks. Elaborate dioramas and storyboards were designed around his work to help secure the financing needed to finish filming the American version, and to also settle distribution rights with theaters.

Plans for the 36-story tall Godzilla to stomp across Milwaukee landmarks, however, were abandoned shortly after the financial pitch started in 1956.

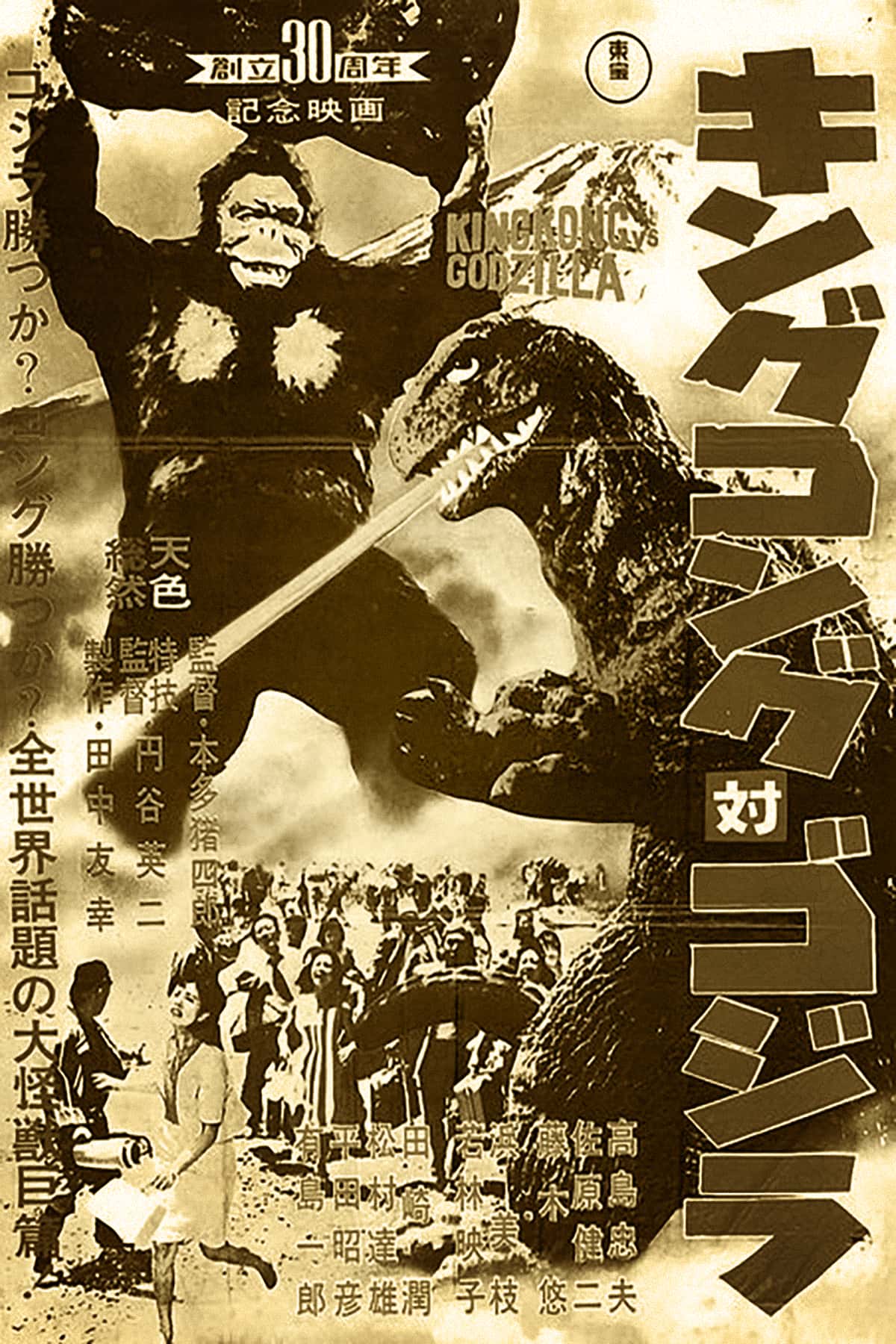

“Trade publications at the time attributed the change of plans to the Soviet–Japanese Joint Declaration of 1956, which returned the Shikotan and Habomai islands to Japan,” said Shelby.

Toho Studios withdrew its American distribution rights to make the 1956 sequel “Godzilla in Habomai,” which went on to break box office records that year.

But Shelby felt another issue was at play, that sabotaged Milwaukee from playing host to the “King of Monsters.”

“When the small Japanese film crew met with Milwaukee property owners to scout locations, they did not realized how prominent the German language was still spoken in the city,” said Shelby. “I think that cultural legacy conflicted with their image of post-war America, and made them concerned about forming another partnership involving Germans.”

With the plans to film in Milwaukee abandoned, Mueller was allowed to keep the model buildings he created. How much he was paid for the work was never disclosed. He continued to work on the project for years after the failed movie production was forgotten. His miniature city of Milwaukee eventually included 60 blocks of downtown with 200 buildings.

Shelby grew up in the 1970s hearing stories about the Godzilla movie production from his father Erhard, who had been employed by the Schuelke Company and worked with Mueller. Erhard had also saved some photographs from a collection that Mueller took of his model work in the late 1960s.

Mueller completed his cityscape in 1969. After his death in October 1971, the models went on auction and were eventually acquired by the Milwaukee County Historical Society. Before 2020, the models had remained in storage since they were last displayed in 1984. Because they were so intricately detailed and accurate, they required a lot of preparation for storage and space to display.

When the Milwaukee County Historical Society unpacked Mueller’s miniature Milwaukee models before the pandemic hit in February 2020, Shelby photographed the displays using 35mm film and his father’s old Leica camera. But it would be months before he could send the rolls in to have developed.

“I wanted to recreate the sketches and snapshots that I remembered Hernando giving my father. They were lost years ago, and I am not much of an artist to try drawing them,” added Shelby. “So, being able to re-take those pictures is my way to honor Hernando’s work and preserve the memory of a cool project that could have been pivotal for Milwaukee’s post-war stature.”

A heavily edited version of “Godzilla in Habomai” was released theatrically in the United States on June 2, 1959 by Warner Brothers Pictures, under the title “Gigantis, the Fire Monster.”

Nathan Shelby / Toho Co., Ltd. 東宝株式会社

This article is our first attempt to create a fictional “mockunentary” in the parody tradition of April Fools’ Day.