The Cooper Do-Nuts Riot of May 1959. The Compton’s Cafeteria Riot of August 1966. The Black Cat Protests of February 1967. Few of these early LGBTQ uprisings ever made news headlines, and few if any factual police records exist from those incidents.

As the greatest generation continues to leave us, the actual course of these events has been slowly evaporating into a hidden history. As a result, many people today believe that LGBTQ history began with New York’s Stonewall Riots of 1969.

But eight years before Stonewall, Milwaukee was the scene of an early uprising unlike anything local police had ever seen before. On Saturday night, August 5, 1961, four troublemakers got more trouble than they bargained for at the Black Nite located on 400 N. Plankinton Avenue, one of Milwaukee’s most popular gay bars of the time.

Earlier that night, the four servicemen had found a nearly empty bar and a 4-1 fight against the bouncer. Upon their return later, they found a packed bar of 75 patrons ready and willing to defend their turf by any means necessary.

“One of the guys came at me and said, ‘OK you sick faggot, come on.’ I popped him right there, and the blood sprayed, and he fell to the ground,” said Josie Carter, contributor to the Wisconsin LGBT History Project in 2011. “I’ll never forget that as long as I live. He started it, but I stopped it. I may be a ‘faggot,’ but I’m the one who stopped it.”

The servicemen fled the bar, took their injured friend to the County Emergency Hospital, and went back to the Kane Place tavern. They rounded up a dozen men and decided to go back Downtown and “clean up the Black Nite.”

“We didn’t start anything, but we sure as hell finished it,” said Carter. “Those guys only came down there to cause trouble. When he tried to kick them out, they all tried to fight him. And I thought, ‘Oh no, you’re not going to hurt my husband.’ I went out there with a beer bottle in each hand, ready to knock some heads.”

Wally Whetham later reported that “this gang came in and started tearing the bar apart, and the bar fought back.”

“And then the cops came down, and put them all in a paddy wagon, and took them to jail,” said Carter. “They said, ‘You have no business coming down here and harassing these people. The police were good to me back then. They took care of me and taught me how to stay out of trouble. I never had no problem with the police, as long as I didn’t make problems.”

While Whetham and his patrons cleaned up the carnage, the four servicemen were charged with disorderly conduct. Unfortunately, Judge Christ T. Seraphim later dismissed their charges due to “lack of evidence.”

“I have never lived in fear. All someone can do is beat me up, but believe me, if I see them again, anywhere, I will walk up to them and tap them on the shoulder,” added Josie. “‘Remember me?’ I’ll say. And they’ll remember me. I promise you that.”

I am thankful for the work that went into the Wisconsin LGBT History Project, so that we can all learn more about the history of Pride in Wisconsin together. I serve in different roles in our LGBTQ community, but I have always seen myself as an educator and storyteller.

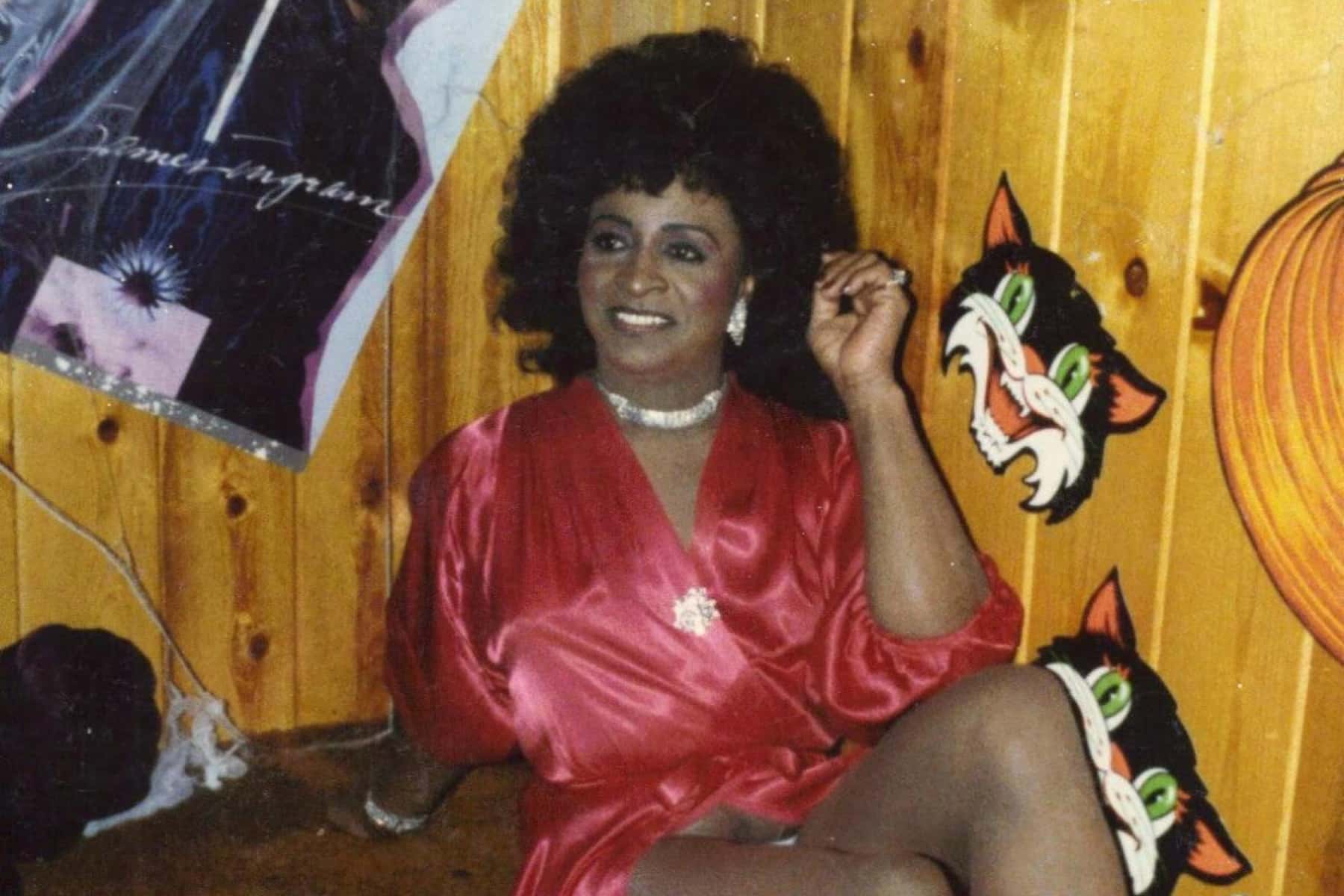

As a Navy veteran, Josie Carter was an American hero. She toured the world while serving her country, traveling to New Zealand, Fiji, Japan, and Hawaii. She was talented and charming, saying that she saw herself as more of a personality than a performer. She was employed as a machine operator, and worked her way to be promoted as a foreman. She remained in that job until she retired.

Josie Carter was also known as a socialite and hostess, and was paid to make club appearances. She organized glamorous parties in the 1970s, and adopted many children into her chosen family throughout her 64 years of life.

She also had a biological son. He lived with his biological mother until age 3. The young woman struggled with drug addiction, and Josie went to court for custody. With her partner Wayne, they fought and won. They lived together until Wayne became ill. Josie cared for him until he passed away.

She was also a mother to many young people in the community as well. Her son never fully accepted Josie, and banned her chosen family from attending her funeral in 2014. Her son was almost arrested after brandishing a gun to keep her other loved ones away.

I mention this to illustrate the power and privilege dynamic that every Black Queer person suffers through within our own families. Fear, bigotry, and bias get the final say when your child is Queer and Black, not love and hope.

It is based on our family’s fears of what other people will think, how other people will treat us. While knowing that our lives will be marginalized, that we will be targeted, excluded, and discriminated against, knowing that we will face all of that – including physical violence.

Our families – the people we love and that are supposed to protect us and give us the tools to protect ourselves – are often more cruel to us than strangers could ever be. “Deadnaming,” misgendering, micro aggressions, trying to punish or intimidate us trying to pray the gay away.

I have seen cis-hetero people cling to the gender binary and tradition. They refuse to change or adapt their language, change their behavior, or even show us compassion and understanding. They often blame us for situations that were not in our control. I want us to get to a place in our families where it doesn’t matter how we identify.

If you and I are family and I see that something is hurting you, bothering you, making you feel uncomfortable, our families should put in the work to change. LGBTQ youth are fighting for survival from their families everyday. Most end up on the street, or are left in even more vulnerable situations at a time when they need community and support the most.

Those of us who are lucky enough to have our families in our lives often suffer through it in silence, often compartmentalize our states of being, and are often the punching bags of our family dynamics.

Josie was also a childhood sexual assault survivor, something else I relate with her. I don’t mention that to support the misconception and basis for Transness or Queerness – because it isn’t. I believe the ways we express ourselves and develop our identities as youth makes us more vulnerable targets of abuse, humiliation, and predatory sexual assault.

She was sexually assaulted throughout her youth and young adulthood, beginning her transition process at 15 years old in the 1950s. I’m so angry to learn all of this in her story, but I’m not surprised. I feel her sadness, I feel her fear, I hear the voices telling her it’s her fault, she should have been smarter or better or braver. The lie that those things would make her safer.

I’m not surprised because I have faced sexual assault all throughout my own life. The physical violence I described doesn’t even begin to present the full scope of the sexual violence, manipulation, and solicitation we as Trans womxn face.

Josie wouldn’t let that stop her. I’m not going to let it stop me. And so many of my sisters, family, and friends walk that walk as well. Josie didn’t want to be known for the Black Nite Brawl. She didn’t want awards or accolades. She didn’t base her sense of self or survival on others. She kept the control of her life in her own hands and was proud of what she accomplished.

She was so candid in her interview for the oral history project, it blew me away. Josie said they made all of their drag clothes, and wore layers of mens clothing to conceal it when they weren’t safe. Years before I transitioned, I was working in retail and I would do that too so people wouldn’t harass me on the street. It was just one of the things that resonated with me – there are so many others.

She was fierce, bold, and she started so young – way before the age that I did. That’s something we talk about often in the transgender community, what age we start as if it’s some determinant. But I believe we each transition at the right time for us, and no one can make that decision for us, or stop the process. It is one of the old adages we all talk about in our communities.

I began a mental transition in my early twenties, and started to full transition a few years after. I honestly don’t think I could have started before that – from lack of a complete understanding. And out of circumstances – due to our families and communities – all the bias turning them against us, as sexually diverse people and as gender diverse people.

I lacked a viable relationship with those histories to guide me. I also had struggles to understand myself, and how to follow the path that God was preparing just for me. I had a Trans Aunt and her name was Ms. Daisy. But she passed before I was born, and I didn’t know about her until well into my own transition. It is an example of what was lost from that lack of understanding.

My Aunt struggled, and she struggled with the law. That is too often a reality for all of us – including myself. As Black people, we are all one bad step, one emergency, or one discriminatory eye away from having everything – including our livelihoods and our lives – taken away.

I say her name because knowing more about her might have made a difference, instead letting her be erased by time. My Aunt too was beautiful, she too was Black, she too lived and fought and loved like Josie, like me, like Ms. Tyra, a founding member of SHEBA. These ladies were gems and gardeners and they planted seeds with their power, with their stories, with their transitions, to make a way for girls like me decades later.

I have two chosen family kids and I love them. I pray for them and myself, and our girls. We have check-ins and meetings, and try to help each other. But often we either don’t know how to help, or don’t have what we need, or aren’t even stable enough ourselves to be there for our girls the way we want. Yet we still wake-up and go to bed knowing that we are in perpetual danger.

There is an epidemic of Black Trans womxn being killed in this country. We as the Black community have to leave the fragile hierarchies of White cisheteronormativity at the door and realize that Black Queer and Trans issues are Black issues. Black Queer and Trans Lives Matter everyday of the year.

I have been made aware of five violent attacks against Black Trans womxn. So far this year, my daughter was attacked as a 16 -year-old here in Milwaukee, the same place where I’ve been marching, advocating, and fighting. The violence we face as Trans womxn of color is not just a national epidemic, it is local. In the last few years there have been two girls who were killed in other states that were from Milwaukee.

We can’t keep living through a cruel lens of Russian Roulette. The relief of knowing we made it through another day is a feeling that every Black Trans and gender non-conforming person feels.

In 2021, we as a Trans and Queer community see our collective visibility as a tool. We see the lack of stability and lack of resources as reasons to fight with the platforms we have available. People like Josie, Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Riviera, Miss Major, and Monica Roberts made it possible to access and leverage those tools to continue working for change.

We have to keep up the fight to make sure that our next generation is not stuck in the same place, having the same conversations that aren’t going anywhere – being the determining factor in our lives. This is where we have to build power for ourselves and create seats at old tables. We also have to build new tables, for us to control our narratives and to again make sure that future generations are better equipped to fight back than we were.

Facing violence and injustice is something we all live with everyday, just like Josie did. We honor her and her sisters. Rest in power Josie Carter, you will not be forgotten. You were beautiful and bold and most importantly – you were loved. You were able to know what radical love is. We carry that with us often for people who don’t deserve our kindness.

Elle Halo

Lee Matz and Wisconsin LGBTQ History Project