Kyrgyzstan is beautiful. But it is also a country in limbo. Suspended between dependence and decolonization, this condition is partly the result of more than a century under Russian control, and partly the ongoing challenge of living in Russia’s shadow.

Planning ahead for my semester teaching in Bishkek, I arrived with a basic knowledge of Kyrgyz history and some familiarity with current events. I expected to encounter “the hangover” from Soviet socialism, it is a legacy I have also seen in Eastern Europe. Sure enough, Kyrgyzstan suffers from corruption, institutionalized mediocrity, propaganda, and pangs of communist nostalgia.

But in Kyrgyzstan, I found things even to be more complex. Among the various reasons, I think the most important are the country’s relative isolation from the West and its proximity to Russia. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine has also stirred things up.

The story of Russia in Kyrgyzstan is nearly 150 years old, and it is telling how that often-brutal history is remembered. Exhibits in the State History Museum – and likely history textbooks too, carefully navigate the colonial period, the 1916 massacres, the Stalinist purges, and so on. Some of the facts are watered down and some are conveniently left out. Some darker truths have been recovered and brought to light, but many truths – like most of the victims – are buried beyond recollection.

The foregrounded history is of the Great Patriotic War – as World War II is called. It is a story of Kyrgyz bravery, sacrifice, and loyalty. There is truth in that. One in every four Kyrgyz was mobilized into the Red Army and over half never returned. Nearly every Kyrgyz family suffered losses.

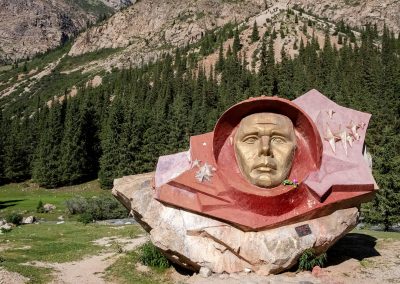

It is right to remember those who served. In Bishkek’s Victory Square, there is a red granite monument shaped like the frame of a giant yurt. An eternal flame burns below it. There are monuments, plaques, and statues of heroic soldiers and generals across the city. Victory Day is a day of parades throughout the country. But here is the thing: all of these heroes are wearing Russian uniforms. Honor, patriotism, and loyalty to Russia are intertwined.

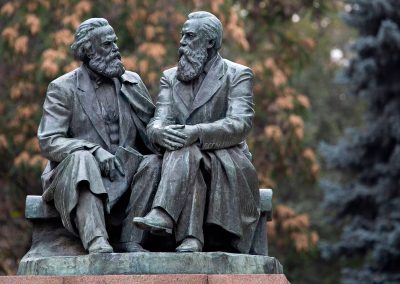

A few weeks after my arrival, I attended a concert at Bishkek’s elegant Opera and Ballet Theatre. The building has been there since 1930 and was the first European-style theatre in the country. The orchestra played Tchaikovsky, Mozart, Verdi, and Shostakovich, much of it beautifully. As the concert ended and the mixed Kyrgyz and Russian audience stood to applaud, the depth of Russia’s cultural impact was dawning on me. Classical music and dance, theatre, Western literature, museums, higher education, popular music, television and movies – Russia brought them all. Russia brought the modern world to Kyrgyzstan.

Of course, there is Kyrgyz culture apart from European arts and education. The epic of Manas is revered, he is the central cultural hero. In Bishkek and elsewhere there are statues of Manas and other Kyrgyz heroes. There are excellent exhibits on the pre-colonial tribes in the museum. Kyrgyz crafts, folkways, horsemanship and nomadic sports are celebrated. There is also a growing emphasis on Kyrgyz culture, a Kyrgyz theatre and arts academies and various schools and universities where classes are in Kyrgyz.

But there is no escaping the fact that modern Kyrgyz identity is also partly Russian. Chinghiz Aitmatov, the country’s greatest writer and most important modern cultural figure, was educated in Russia and honed his craft in the context of the great Russian literary tradition. He wrote more in Russian than in Kyrgyz.

Small wonder then, that the old established cultural institutions and much of the educated class are still, at least in part, aligned with Russia. To a significant degree, their intellectual lineage – their cultural DNA – is Russian. This affinity is not necessarily political allegiance, but the boundaries do seem to blur.

For instance, I met a young Kyrgyz-Russian theatre director who trained at a Moscow academy and was mentored by a well-known Russian director. He told me he had been hired to direct a production at Bishkek’s Russian Theatre, but when they learned that he had attended an early protest against the invasion of Ukraine, the offer was rescinded.

I was told of an undergraduate at the American University of Central Asia who proposed to write her thesis on “Kyrgyz Decolonization.” Reportedly, the topic was rejected by her faculty advisor. The boundaries blur.

I have heard experts make the claim that Russian intelligence has infiltrated public institutions throughout Kyrgyzstan. I find that easy to believe.

Still, it seems to me that Russia’s strongest leverage in Kyrgyzstan is not history, patriotism, language, culture, or even Russian agents in strategic positions. It is the ruble.

The largest Kyrgyz diaspora is in Russia. One million Kyrgyz citizens work in Russia and send remittances home. Kyrgyzstan is a member of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU or EAEU), along with Kazakhstan, Armenia, Belarus, and Russia. It is generally acknowledged that this is Putin’s club and he calls the shots.

Kyrgyzstan’s chief partners in exports and imports are China and Russia. Turkey and Kazakhstan are important but the other large economies are too far off to play much of a role. Russia has a military base in Kyrgyzstan. Russia controls the gas company and the flow of petrol.

Finally, despite financial aid and investments from Western governments, NGOs and other nations, Kyrgyzstan is deep in debt to Russia and still borrowing.

THE IMPACT OF THE WAR

In February 2022, Kyrgyz President Japarov was quick to voice support for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Of course, like most of the rest of the world, he was anticipating it would be over in a matter of days.

As the weeks wore on, Japarov restated the Kyrgyz position as neutral. Public demonstrations, either for or against Russia’s “military operation,” were banned. The government also made it clear that Kyrgyz citizens may not fight in foreign conflicts. That being said, reports have come to light of Central Asian workers in Russia being pressured to join the army. And of the estimated 50,000 “recruits” from Russian prisons into the Wagner Group, a large number were reportedly Central Asians.

The Kyrgyz population is divided on the war. Late last fall, in a telephone poll of 1,500 people, about half were inclined to blame Ukraine or the U.S. for the war, though only 41% said they were paying close attention. Perceptions, however, are often shaped by media and Kyrgyz State TV is Russian programming. Older viewers generally watch TV instead of searching on the internet, which offers more perspectives. A poll of younger Kyrgyz would no doubt lean much more toward blaming Russia.

Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of Russian exiles have arrived in Central Asia. Part of Kyrgyzstan’s appeal is that Russian nationals can enter without a visa or even a passport. A regular Russian ID card is accepted by Kyrgyz passport control. Most are young men who fled the conscription last fall. Others are professionals and tech-elites who left anticipating the war’s economic consequences in Russia. In general, the Kyrgyz population has welcomed them.

Kyrgyzstan is a poor country so any devaluation of the ruble creates hardships. But in Bishkek, the restaurants have been busy. Hotels and hostels have been full and rent prices have skyrocketed. The rent for my apartment was significantly more than I had expected to pay, though it could have been worse. Some tenants have been turned out to make way for higher-paying Russians.

On the international front, the U.S. and E.U. are well aware that Russia and Belarus have been circumventing sanctions by smuggling goods through Central Asia. They have addressed the issue more than once and with growing concern. In July, after several months of warnings, the U.S. introduced new sanctions that target 18 individuals and 120 entities in both Russia and Kyrgyzstan. This raises serious questions. Can Kyrgyzstan refuse to aid her allies in the Eurasian Economic Union? How much collusion will the West tolerate? And how long can Kyrgyzstan stay neutral?

On the other hand, thanks to the shifting geopolitics and Russia’s preoccupation in Ukraine, the war may also benefit Kyrgyzstan. For example, China has recently presented each of the five Central Asian heads of state with a bouquet of investment and development proposals. The most promising for Kyrgyzstan looks to be the plan to build a railway from northwest China through the mountains, then through southern Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan en route to Europe. This would bypass Russian railways and tariffs.

There has also been a steady stream of U.S. officials in the region. President Biden recently invited the Central Asian heads of state to a September summit in New York. Known as C5+1, they will discuss such topics as the economy, energy, environment, and shared security. This will be the first Central Asian summit with an American President, and it highlights the growing strategic significance of the region.

Perhaps most importantly, Russia is losing the PR battle. The Ukraine war began in 2014 with Russia’s invasion of Crimea, followed by the tepid acquiescence of the West. Russian propaganda won the day. But since the end of February 2022, the script has flipped and most of the world now sees Ukraine’s valor and ingenuity standing in stark contrast to Russia’s barbarism. For much of Western Europe this has been a wake-up call, for Eastern Europe a grim reminder, and for the Baltic states a big “We told you so.” Among the many repercussions of this shift is a growing “de-colonial awareness” throughout the former Soviet bloc, including Central Asia.

In Bishkek, President Japarov just signed a constitutional law that aims to make the Kyrgyz language mandatory throughout the country’s government, in education, municipalities, businesses, and civic organizations. At least 60% of all public and private radio and TV broadcasts must now be in Kyrgyz. This may develop slowly but I believe it represents a major step in the process of decolonization. Perhaps it was inevitable sooner or later, but I doubt it would be happening now, if not for the international response to the current situation in Ukraine.

Of course, there is opposition in both Moscow and Bishkek and talk of “discrimination” against Russian speakers. Some scholars have claimed the Kyrgyz language is not yet modernized enough. But Kazakhstan passed comparable laws a decade back and it has largely been successful.

It is impossible to see what the future holds for Kyrgyzstan, but the country’s relationship with Russia is certainly changing. The Kyrgyz population is predominantly young. Most were born after independence and many – like most of my students – were born in the 21st century. By and large, they are welcoming change. They believe in democracy and a civil society. Many want to come to the West, but most will stay and build their lives in Kyrgyzstan. My best hopes for the country’s future are with them.

Editor’s Note: The casual travel images taken by Edward Morgan in Kyrgyzstan have been augmented by Milwaukee Independent with stock photos. The editorial decision was made to enhance the visual representations of places or situations in Kyrgyzstan that appear in this feature. Contributing photographers are credited as a group to avoid any misrepresentation.

Chris Lawrence, Collab Media, Iwciagr, JJay69, Kasak Photo, Matyas Rehak, Mehmet O., Oleg Znamenskiy, Schankz, Stocker Plus, Swift21, Teow Cek Chuan, and Vagabjorn