I recently returned from Kyrgyzstan, a remarkable half-year experience that enriched my life and changed my perspective in various ways. Kyrgyzstan is a small, landlocked country in Central Asia. The total population is less than seven million. I was there as a Fulbright Scholar, teaching in the capital city of Bishkek, with a population of one million.

I taught courses in English and Journalism at Ala-Too International University, and Creative Storymaking for the TV and Film department at the American University of Central Asia. My students and colleagues were warm and appreciative and the work was rewarding, though really not so different from other teaching I have done. The country and culture though, were quite different.

I arrived in mid-January with a week to adjust before classes began. Bishkek was not any colder than Milwaukee in mid-winter, but the city has terrible winter smog because so many buildings are heated with “dirty” brown coal. The smell reminded me of Dublin, only more so. The bigger challenge was functioning day to day with my basic Russian. Outside of the universities, I did not encounter many English speakers.

The Kyrgyz descended from nomadic Turkic tribes who traversed the mountains and steppes of Central Asia. In the mid-19th century, the Russian Empire conquered the region, drew boundaries, and gradually forced the nomads to settle. Russian colonists claimed the best land and the Russian language became the lingua franca.

In 1991, as the Soviet Union finally collapsed, the Kyrgyz declared their independence. Two small revolutions and six presidents later, the country is slightly more democratic than its Central Asian neighbors, with a “semi-authoritarian” constitutional government. August 31 is the 32nd anniversary of Independence Day. But as I learned throughout my stay, Kyrgyz independence from Russia is a work in progress.

After independence, the country’s Russian population decreased but the language remained dominant in the capital and throughout the country in government, higher education, public institutions, and so on. This is partly why at first, I thought the people in Bishkek seemed more Eastern European than Asian. That perception changed over time. Regardless of language, the Kyrgyz have a warmth and humility that is not Slavic or Eastern European.

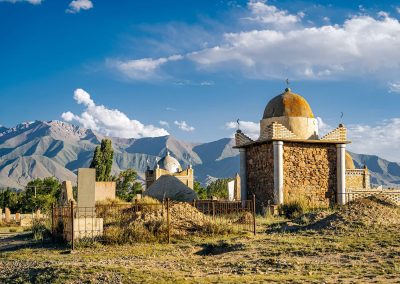

Bishkek is a modern city but the majority of Kyrgyz live in rural areas. Most raise livestock or farm but some work in mining or manufacturing. They prefer to speak Kyrgyz, a Turkic language. They are proud of their culture and many are expert horsemen. They are also predominantly Muslim, though the country is more secular than I had expected.

For instance, I was there during Ramadan, which for practicing Muslims is a month of fasting, sunrise to sunset. Many people fasted, but many did not and this was considered a personal decision. The same is true for women wearing the hijab; many do so but more do not. It is an individual choice. This tolerance may be partly due to the Soviet discouragement of religion, but I think it is also an extension of the culture’s pre-Islamic roots and the individualism of the nomadic tribes.

I was also there for Nooruz, the ancient New Year’s celebration during the spring solstice. Nooruz (or Nowruz) predates Islam so it is discouraged in some Muslim countries. In Bishkek, it is a party. Ala-Too Square was blocked off, full of food stands and souvenir booths, and a stage with huge speakers for pop music performances. At the Hippodrome there was a sports festival with archery, horse races, and a kok-boru tournament. Kok-boru is a team sport played on horseback. It is somewhat like polo but they play with a 70-pound headless goat carcass. The semi-final match I saw was thrilling but dangerous: two riders left the match in ambulances.

In early March, I took an hour’s flight south to lecture at Osh State University. Watching from the plane’s window as we passed over miles and miles of sharp, snowy ridges and peaks, I could see why Kyrgyzstan is called the Switzerland of Central Asia. Over 90 percent of the country is mountainous, with five peaks over 22,965 feet.

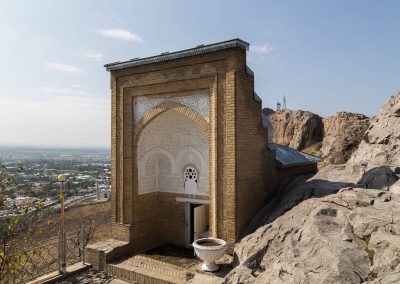

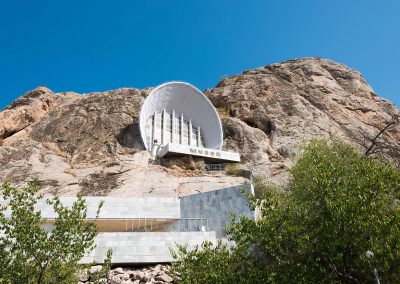

Osh is the country’s second largest city but it feels more like a town. The city is over 3,000 years old and was an important trading stop on the Silk Road. I spent a morning in the Osh bazaar, which they say has been continuous since at least the 8th century. In the afternoon I climbed several hundred stone steps to the top of Sulieman Too, a small mountain shaped like a camel’s back near the center of town. It has been a sacred place for over a thousand years. In the Bronze Age there were ritual sites and settlements on the slopes. Centuries later, Muslims built a shrine at the summit because of a tradition that Solomon (Sulieman) spent a night there. Pilgrims, tourists, and locals visit the mountain.

As warmer weather arrived, I spent some days off in the mountains, riding horses and hiking. It is amazing how many gorgeous mountain valleys there are. Many Kyrgyz come to such places on jailoo, which means “summer pasture” and refers to the high-altitude meadows where the nomadic tribes would take their flocks as the weather got warm. Modern Kyrgyz go on jailoo to escape the hot lowlands and spend a few days, weeks, or months living in yurts like their nomadic ancestors, cooking over a fire, riding horses, and sitting out under the stars at night.

But the one place everyone said I should go was Issyk-Kul, the huge saline lake in the country’s northeast. It seems like all of Bishkek takes a summer vacation there. So, one spring morning I took a bus to Cholpon Ata, a tourist town on the lake’s north shore. The view of the lake is unforgettable. The water is bright blue and a brilliant contrast with the rocky landscape. Across the water, beyond the southern shore, the distant jagged snow-capped Tian Shen Mountains rise up like a mirage.

Issyk-Kul is the heart of Kyrgyzstan. It never freezes, though it is 5,249 feet above sea level and quite cold until mid-summer. More than a hundred rivers and streams flow into the sprawling lake, along with hot springs and glacial melt. It is the second largest alpine lake in the world, the tenth largest lake and the seventh deepest. At its bottom archeologists have found the remains of a 2,500-year-old city.

When my wife came to visit in early June, the one place I had to take her was Issyk-Kul. We spent three days in Karakol, at the east end of the lake. Karakol was a Russian military post and then a Russian resort town. Now it is a growing center for international tourism, with skiing, trekking, and hot springs nearby, plus activities on the lake. We hiked and rode horses into the Jeti-Ögüz gorge and hiked up to the snow line above Jyrgalan Valley. We kayaked in a bay just off the lake, ate fresh fish for lunch, and took an excursion on a former Soviet military boat. The water was still quite cold but I could not resist diving in.

As I think back on it now, diving into that lake is a good metaphor for my Kyrgyzstan trip, from teaching nearly 100 students whose names I could barely pronounce at first, to sitting in a yurt drinking kumis, the fermented mare’s milk that sustained the Turkic nomads and the hordes of Genghis Khan, from stumbling through conversations in Russian with strangers in the street, to long discussions with colleagues and Russian exiles on geopolitics and the war in Ukraine.

These things have changed me and changed my understanding of the world. And of course, I also made many new friends. I am gratified to know I had an impact as a teacher, as a guest, and as a cultural ambassador for democracy. There are good reasons to travel halfway around the world and stay awhile.

Editor’s Note: The casual travel images taken by Edward Morgan in Kyrgyzstan have been augmented by Milwaukee Independent with stock photos. The editorial decision was made to enhance the visual representations of places or situations in Kyrgyzstan that appear in this feature. Contributing photographers are credited as a group to avoid any misrepresentation.

Alexey Arz, Anna Blashenkova, Beibaoke, Borkowska Trippin, Daan Kloeg, Dior3, Dusya Kan, Elena Odareeva, Eric Valenne, Funtay, Hakanyalicn, Hyotographics, Iwciagr, Kasak Photo, Leonid Andronov, Matyas Rehak, Mehmet O., Nastya Smirnova, Oleg Znamenskiy, Oliver Foerstner, Omri Eliyahu, Picture Of Life, Pikoso Kz, Popova Valeriya, Roman Chekhovskoi, Stocker Plus, Thiago B. Trevisan, Vera Larina, and Vittoria Che