Questions are mounting over the criminal complaint filed by the U.S. Department of Justice against Milwaukee County Circuit Court Judge Hannah Dugan, who was arrested April 25, 2025, at the Milwaukee County Courthouse and charged with obstruction and concealing a person from federal authorities.

The government alleges that Judge Dugan interfered with a planned arrest by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents on April 18, when officers attempted to detain Eduardo Flores-Ruiz, a defendant scheduled for a domestic violence hearing in her courtroom.

However, a detailed review of the complaint and courthouse layout has raised multiple red flags, including discrepancies in the government’s description of the building, contradictory observations from federal agents, and evidence that the alleged attempt to “shield” Flores-Ruiz may be based on physically inaccurate claims.

According to the criminal complaint, which includes a sworn affidavit by FBI Special Agent Lindsay Schloemer:

“Despite having been advised of the administrative warrant for the arrest of Flores-Ruiz, Judge

DUGAN then escorted Flores-Ruiz and his counsel out of the courtroom through the ‘jury door,’

which leads to a nonpublic area of the courthouse.”

That assertion is at odds with the architecture of the courthouse’s sixth floor, where Courtroom 615 is located.

Photos and building diagrams show that the jury door cited in the complaint opens into the exact same public hallway as the courtroom’s main entrance, just ten feet apart. Both doors are plainly visible from the hallway.

The jury door does not lead to a nonpublic area, and it does not provide any concealed or privileged path out of the courtroom. It is a secondary entrance, used primarily for in-custody defendants or juror access, but connects to the same corridor where law enforcement agents were already stationed.

According to the affidavit, agents entered Courtroom 615 before the hearing began with the intent of arresting Flores-Ruiz inside the courtroom. That attempt was halted when the courtroom deputy intervened and directed them to wait in the hallway until the hearing was over.

The agents complied and left the courtroom, taking up positions in the public corridor. Their early entry and direct engagement with courtroom staff elevated tensions. It was this initial incursion into court space that triggered the confrontation.

The complaint further states:

“After leaving the Chief Judge’s vestibule and returning to the public hallway, DEA Agent A reported that Flores-Ruiz and his attorney were in the public hallway. DEA Agent B also observed Flores-Ruiz and his attorney in the hallway near Courtroom 615 and noted that Flores-Ruiz was looking around the hallway.”

This section of the affidavit directly acknowledges that federal agents saw Flores-Ruiz and his attorney in the public corridor after the court session. Despite already being inside the courthouse with an administrative warrant, no arrest was made at that time.

The agents did not attempt to detain Flores-Ruiz, nor did they intervene or prevent him from leaving, a point that appears to undercut the claim that Judge Dugan’s actions actively obstructed the arrest.

The affidavit repeatedly refers to an “administrative warrant” issued for Flores-Ruiz. But unlike a judicial warrant signed by a federal judge, an administrative warrant does not authorize the same authority under federal law. ICE agents cannot compel court staff to assist, and they carry no authority beyond the issuing agency.

It is an internal directive used primarily in immigration enforcement, not a court order. That distinction is critical. While a judicial warrant allows for entry, seizure, and detention under federal law, an administrative warrant has no criminal enforcement power and does not override state court procedures.

Elsewhere in the affidavit, the agent suggests evasive behavior based on the path Flores-Ruiz took as he exited the building. The complaint reads:

“From different vantage points, both agents observed Flores-Ruiz and his counsel walk briskly towards the elevator bank on the south end of the sixth floor. I am familiar with the layout of the sixth floor of the courthouse and know that the south elevators are not the closest elevators to Courtroom 615, and therefore it appears that Flores-Ruiz and his counsel elected not to use the closest elevator bank to Courtroom 615.”

This statement insinuates that Flores-Ruiz was attempting to avoid detection by deliberately using a less convenient route. But a review of the sixth-floor evacuation map shows that both the north and south elevator banks are located in the same public hallway, separated by a relatively short distance.

In fact, the south elevator bank is the only one that serves the courthouse’s basement level, where the 9th Street public entrance and exit are located. It is the same entrance Flores-Ruiz reportedly used to enter the courthouse earlier that morning.

The implication that Flores-Ruiz and his attorney bypassed the closest elevator to avoid law enforcement is further weakened by the building’s design. Signage near both elevator banks clearly directs users to different courthouse levels, and the south elevators are marked for basement access. Any reasonable route out of the building, using the same entrance as arrival, would have required the use of the south elevators.

Throughout the complaint, Schloemer repeatedly writes that she is “familiar with the layout of the sixth floor of the courthouse,” invoking that familiarity to reinforce her credibility as a federal affiant. Yet the specific assertions regarding door access, elevator placement, and routing decisions are not supported by the physical evidence of the courthouse itself.

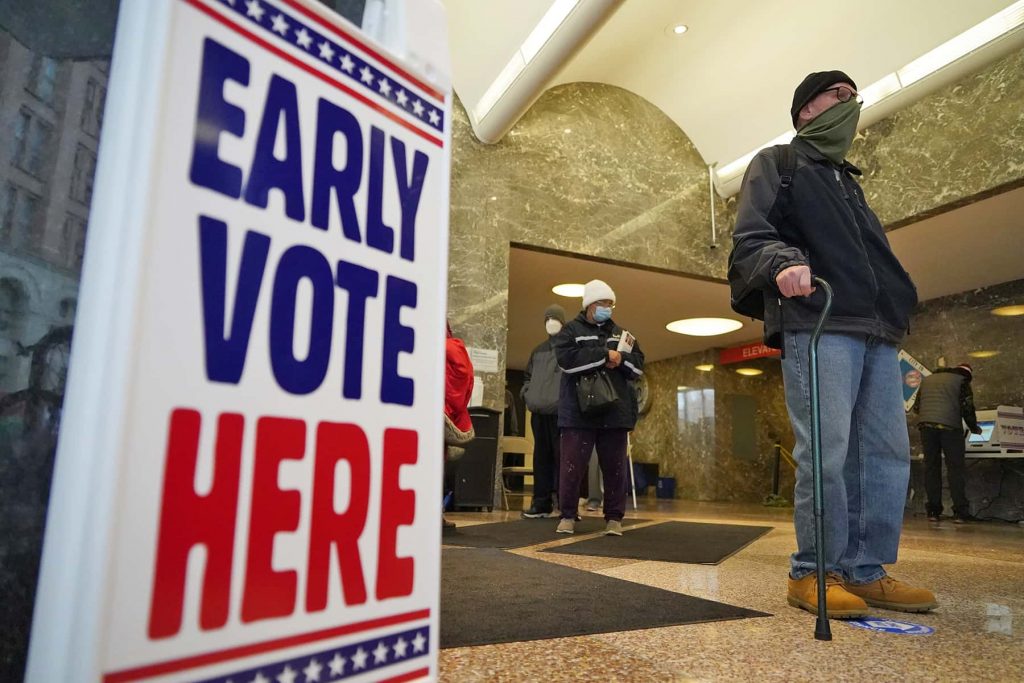

Additional images recorded on May 22 by Milwaukee Independent visually contradict the affidavit’s description of the courthouse layout. The photo series, taken after the events in question, visually documents the full sixth-floor corridor, fire exit signage, courtroom door placement, and the relative positions of both elevator banks.

These photos were reviewed against the complaint’s sworn narrative and the building’s posted emergency evacuation map. They confirm that the jury door cited by federal agents does not access any restricted or nonpublic area. Instead, it opens directly into the same public hallway as the courtroom’s main entrance, less than ten feet apart, and with no architectural divider or security checkpoint between them.

In parallel to these new still photos, two Milwaukee television stations released security camera footage that captured segments of the April 18 confrontation between Judge Dugan and federal agents.

While the video was distributed widely online and broadcast repeatedly on-air, both stations neglected to provide adequate interpretive analysis, spatial orientation, or editorial context with the initial release.

These omissions require viewers to make uninformed assumptions and result in misinterpretations, which also foster the impression of evasion or secrecy. It also lacks establishing context from the courthouse’s spatial design related to the FBI’s criminal complaint.

But aside from the media mishandling, the cumulative impact of these documented contradictions is significant. The claim that Judge Dugan led Flores-Ruiz into a restricted area is not supported by the floor plan. The implication that agents were circumvented is refuted by their own statement that they observed Flores-Ruiz in the public hallway. And the suggestion that Flores-Ruiz’s choice of elevator bank was evasive is contradicted by the building’s only basement-access route.

These factual contradictions are at the center of calls for accountability from legal experts and civil rights advocates who say the affidavit’s inaccuracies are structural to the charges brought against Judge Dugan.

At stake is whether the federal government has misrepresented standard courthouse operations to frame a public official for obstruction.

Central to that concern is the role played by sworn statements in the federal criminal complaint. Affidavits like Schloemer’s are meant to establish probable cause, a threshold that allows for arrests, bail conditions, and legal proceedings. If foundational claims in such a document are later shown to be false, misleading, or materially incomplete, it can severely undermine both the prosecution’s credibility and the legitimacy of the case.

Legal observers have also questioned the logic of the obstruction charge in light of the agents own actions. If, as stated in the affidavit, federal agents were aware that Flores-Ruiz was present in a public area and made no move to arrest him at that time, it becomes difficult to assert that Judge Dugan’s conduct was the deciding factor in the situation. The agents voluntary delay contradicts the narrative that they were actively prevented from executing a warrant.

In addition, the framing of Judge Dugan’s alleged conduct is built heavily on inferences, not concrete acts. The complaint does not claim that Judge Dugan told Flores-Ruiz to evade, nor does it document any statement instructing or encouraging concealment.

Instead, it relies on descriptions of her demeanor, such as being “visibly angry,” and routine courtroom activity, such as entering chambers or interacting with her deputy. Those actions, while subject to interpretation, are not uncommon in judicial settings where tensions rise or scheduling conflicts occur.

The complaint’s claim that Flores-Ruiz was “pushed through” the docket without the involvement of the prosecuting attorney also lacks documentary clarity. Flores-Ruiz’s case was not called in open court, and his hearing was reportedly adjourned without notice to the state prosecutor or victim advocates. But the cause and context of that docket adjustment, including whether it was procedural, logistical, or intentional, is not supported with transcripts or court orders in the document.

Photographic evidence taken on May 22 appears to directly contradict the complaint’s most serious allegations. Images show both the main courtroom door and jury door of Courtroom 615 opening into the same public hallway. Photos of the south elevator bank confirm it as the only route with basement access. Signage near both exits shows this distinction. Directional arrows and emergency floor plans clearly mark the hallway as a continuous shared corridor, not a segmented space with secret access points.

Critics have emphasized that the physical facts of the building should not be subject to narrative interpretation in a sworn affidavit. The layout is fixed, the signage is permanent, and the building’s function has been consistent for years. That a federal complaint would misstate these basic spatial relationships should draw renewed attention to the process of affidavit review and the standards used in high-profile prosecutions.

Judge Dugan, a sitting judge with a long record of public service, has maintained her innocence by entering a plea of not guilty in Federal court.

While the legal outcome remains to be determined, the broader implications are already evident. The integrity of the affidavit, the accuracy of its claims, and the manner in which federal agents carried out their operation are now central to the public’s assessment of the case.

For a prosecution that relies so heavily on physical layout and procedural timing, the facts of the courthouse may prove more compelling than the government’s contrived narrative.

© Photo

Lee Matz