In anticipation of the month-long series of free, citizen-led neighborhood explorations called Jane’s Walk MKE that I am helping to coordinate this May, I have been contemplating how and why Milwaukee walks by considering how and why humans have walked in the past.

This exercise has led me down a rabbit hole of research that I have only begun to scratch – as far back as Homo erectus on the plains of Africa, as unexpectedly as 1920s France, and as recently as the March for Our Lives – but one that has provided me with new pathways for my personal wonderings and wanderings and, I hope, for the creative journey of Milwaukee.

Early humans foraged miles for food. Young people discovered themselves on quests and walkabouts. Aristotle’s followers were called the Peripatetics. Romantics like Wordsworth walked to escape the din of city life, and Transcendentalists like Thoreau walked to get closer to the “natural” condition of humans. Painters, captivated by the mystique of walking, have celebrated walkers of all kinds: Hokusai painted a multitude of mountain climbers, Seurat the promenade on the Island of Grand Jatte, Friedrich a lone “Wanderer Above the Sea Fog” with walking stick in hand, and even Munch’s scream was inspired by a leisurely evening walk with friends. Marching with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Selma, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel famously said, “I prayed with my feet.”

Black Lives Matter have been marching for years to end racism and police brutality, and just this past weekend, hundreds of thousands joined high school students to march for stricter gun safety laws. And for almost seven months, too, Milwaukeeans have been celebrating the 50th anniversary of the marches of 1967-68, when hundreds, even thousands, of people marched every night for two-hundred nights to fight for fair housing for all residents. Whether we’re walking for survival, revelation, or human rights, ours is a walking species.

And yet, on this sunny Sunday, as I sit in my home office, I notice I’ve logged a mere 1,806 steps. Earlier, I even drove the six blocks to my part-time job (as I do most days, I admit, ashamedly) for our monthly staff meeting. According to a recent study, Americans walk an average of only 5,000 steps per day (about 2.5 miles), about half of, say, Australia’s or Switzerland’s averages, and nowhere near the average Amish male adult (18,000 steps). Americans are obviously walking, but seemingly in shorter spurts, for practical reasons: get to car, get from car into work, walk from place to place at work, get from car to store, walk around store, walk the dog. Even with the rise of fitness watches to motivate us, Americans like me are lagging behind.

With each new year, however, I notice ways in which Milwaukee is trying to catch up and join this heritage of human walking as a practice. It’s not like middle school students are walking through the streets seeking visions or business seers are pacing through the halls of new office towers with their followers, seeking truth. But residents, politicians, and activists are indeed making strides to change the way Milwaukeeans move throughout the city – and why they walk.

To foster a healthier citizenry, summer initiatives like Mayor Tom Barrett’s Walk 100 Miles with the Mayor and year-round organizations like the Wisconsin Go Hiking Club and others like it log hundreds of collective miles exploring the city and beyond “to promote health and good fellowship by hiking.” And the Wisconsin Bike Fed’s Milwaukee Complete Streets For All campaign encourages healthy neighborhoods through healthy transportation, advocating for safer, more accessible streets for pedestrians, bikers, and vehicles through legislation and tactical urbanism.

In a different way, walking has the potential to expand our perspective, if, of course, our eyes swivel to and fro, up and down (and by “down” I don’t mean down at our cell phone). We can see and appreciate something or someone new in even the most familiar of environments. We can encounter our environment and engage it. As I wrote in my last column, “ If… we change what we see, we can transform how we see. It is only when we zoom in and see each other and the spaces we inhabit more closely that we can begin to zoom out, see the big picture, understand each other…” Walking gives us a chance to witness what urbanist and activist Jane Jacob’s called “an intricate sidewalk ballet” open up before us, a dance of human experiences with which to engage and connect, one that cannot be appreciated by zooming past in a vehicle.

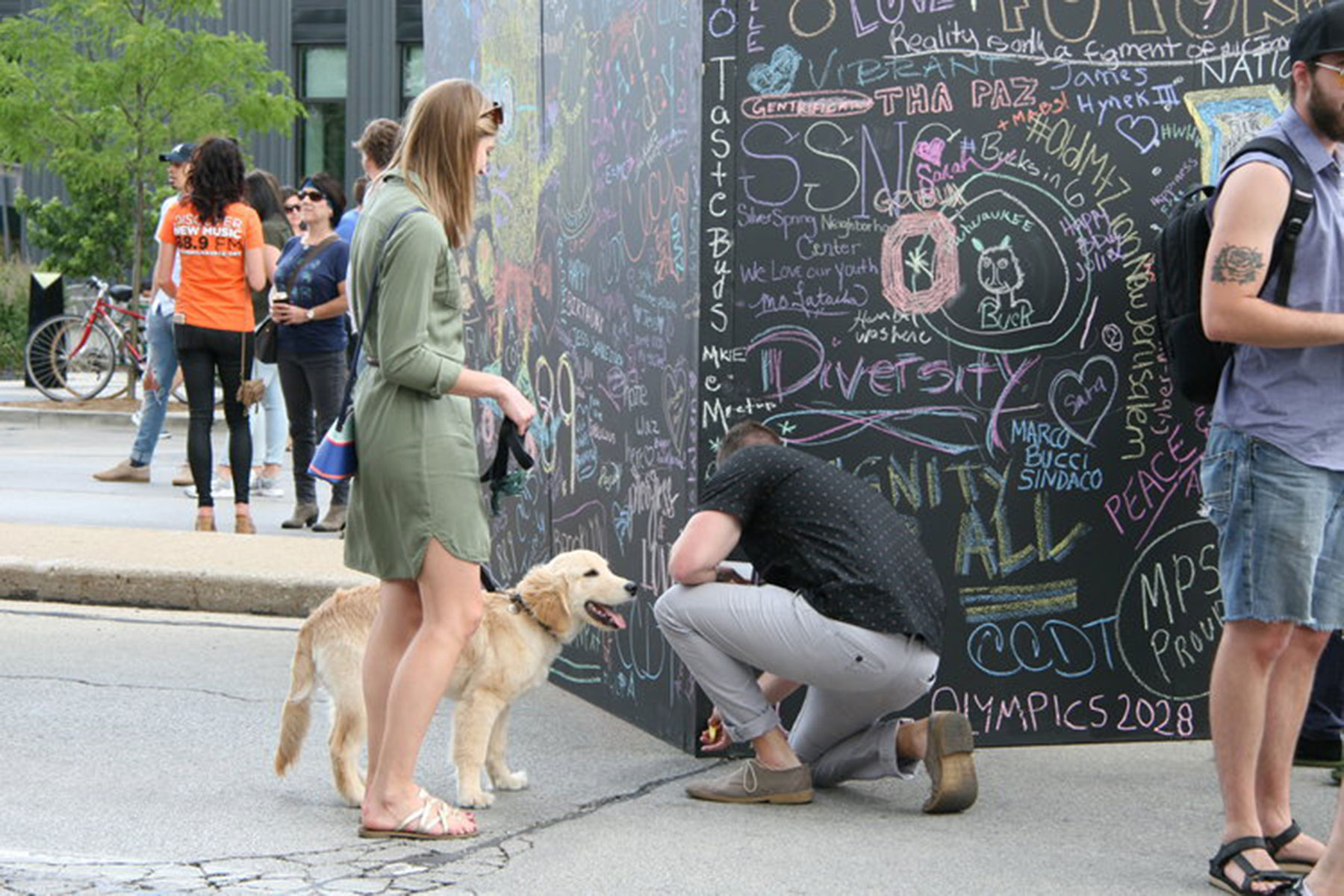

The month-long celebration of Jacobs’ legacy, Jane’s Walk MKE, will take place this May to encourage residents to lead free neighborhood explorations, witness the sidewalk ballet throughout the city, and discuss ways to celebrate and improve it. Projects like ZIP MKE and Milwaukee Stories add a photographic and narrative element to the sidewalk ballet, with journalists from the latter hitting the streets, on foot, in dozens of neighborhoods, to interview the dancers one by one, neighborhood by neighborhood. Indeed, this very news magazine is the result of traversing the city, engaging its residents, and publishing positive news that activates change.

What if, however, in addition to weekday strolls and weekend jaunts, organized and sanctioned walks, campaigns, or news assignments, Milwaukee embraced something a little more… French?

In nineteenth-century French literature, the flâneur was the quintessential (then, always male) stroller characterized by his leisurely, detached observation of the workings of the city. The word flâneur derives from the Old Norse word meaning “to wander with no purpose,” but the flâneur had a very specific purpose: that of detached urban spectator, voyeur, documenter.

Give the flâneur a camera and you have a modern-day street photographer. Imagine walking the entire distance of North Avenue, from the North Point Water Tower to 60th Street, with the primary objective being to document with photographs the banal and quotidian, the old and abandoned, the new and improved. No entering of buildings and very little interaction with residents along the way: only objective, street-level observation of the surface. Lee Matz and several others, including myself, participated in this flâneurie in October of last year, a repeat of the same route Lee had walked two years prior in order to document the life and condition of North Avenue. In a photo essay about our walk, I observed

details in East Side benches, fancy alley fences, red brick crosswalks, and large planters in Uptown Crossing and Lindsay Heights. Peaceful scenes through windows of the newish East Branch library, and dated dining room sets set behind bars at the Milwaukee Mall. The glaring vacancy of lots that conjured up visions of pocket parks with paths, vegetable gardens, and swing sets… Messages of hope scrawled into bridge railings, under which a lone fly fisherman patiently cast his line. Messages of inspiration on a pay-as-you-can cafe further west. Spaces of revival and vibrancy. Spaces of emptiness and potential.

Surely, I would never have encountered what I did along North Avenue had I been a car blur rushing to get downtown or home to Wauwatosa. So what if more individuals and groups took similar strolls, whether sociological like Lee’s or casual (but intense) like the Wisconsin Go Hiking Club’s, and reintroduced walking as a practice of closely reading the city at a more leisurely pace? Imagine a city of flâneurs, men and women, young and old, with watchful eyes on their blocks, in their neighborhoods, reporting out to the community their observations, increasing safety with their presence and visibility and reflecting back to the community its assets and struggles.

Another model for Milwaukee walkers might be the Surrealist art and literary movement of 1920s, which also began in Paris and sought to unlock the unconscious and thereby unlock the imagination. With more than observation as their goal, Surrealist artists would often wander through the city, developing through the very act of walking a critique of modern life, especially any kind of rational, pragmatic order.

According to Lori Waxman, they sought to “revolutionize everyday life” by voicing, with their art, literature, and walking practice, their protest of modern encroachments on creative and leisurely life. One of their rallying cries was against the rise of the automobile at the expense of the pedestrian. In language that could describe aspects of Milwaukee today, Waxman explains the changes to Paris the Surrealists lamented:

irregular pavements gave way to smooth ones, the fluttering light of gas lamps dimmed in favor of electric bulbs, large plazas no longer plunged into dark obscurity at night, pedestrians found themselves herded along newly demarcated sidewalks and crosswalks. Much of this urban refitting was done under the influence of the automobile… along with the related phenomena of noise, exhaust, traffic, and vehicular accidents.

Where previously the streets danced with a kind of ‘disordered ballet’ of pedestrians, horse-drawn carts, vendors, and the occasional automobile, by the mid-1920s a new kind of order reigned: minimum speed limits during rush hour, the division of roads into separate lanes, unidirectional traffic, intersections governed by policemen with batons, and finally the American solution of lighted signals. Each of these measures made the city more navigable by car, more conducive to its fast, flowing circulation, but they also radically altered the situation of the pedestrian, rendering him or her a secondary citizen of the street, one forced to capitulate to the dominance of the automobile…

Waxman consciously or unconsciously uses a similar dance metaphor to Jacobs’ to highlight the confrontation of pedestrian Paris with motorized Paris, a confrontation that is at the forefront of the current Complete Streets movement, perhaps even more so in 2018. In fact, as I write this, an article in the national Streetsblog USA began popping up in my Facebook feed from my friends in the Wisconsin Bike Fed: “Most Milwaukee Drivers Don’t Yield to Pedestrians at Crosswalks.”

To relieve the system shock of losing valuable promenading space to cars, the Surrealists began exploring ways to walk “to re-enchant the action itself.” The founder of Surrealism, writer and poet André Breton, called upon the power of walking to “[remake] life, a life grown diminished by the society in which [Parisians] lived, a life which needed to be found again and intensified.” The Surrealist project was not just nostalgia for life as they once knew it but a direct personal encounter between them and their city to “discover the marvelous in the banal”specially areas of the city not typically perceived as having any importance, whether historical, aesthetic, or utilitarian – and an exploration of “the unconscious, both their own and the city’s.”

While the Romantics escaped their cities temporarily and scoured the countryside’s landscapes to help inform their “inscapes,” the Surrealists remained immersed in city life, waiting to find revelation on the street in their déambulations. They believed that if they could unlock their unconscious – their feelings and thoughts, desires and motivations, their memories – through their walking and their art, then they could also vivify their city with their literary and artistic expressions.

Imagine, then, not only donning the spectacles of the flâneur but also the more reflective role of the Surrealist, walking through Harambee or Riverwest, Clarke Square or Havenwoods, to chart one’s own unconscious as one walks past porches and corner stores, galleries and grasslands. What feelings emerges? What urges? What memories or fantasies? What unspoken story are those porches telling you? What history emerges from the graffitied brick of that corner store? What fantasy for the neighborhood is the new artist’s studio? How can direct personal encounters with our city help us discover potential in the most unexpected places? And how could we, then, express this potential with our voices, our writing, our art?

Similar to the Surrealist project, the Situationist International movement begun by Guy Debord in the mid-1950s to early 1970s birthed psychogeography, described by Debord as “the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals.” In other words, Situationist walkers observed and critiqued how Paris’ geography – especially as it existed with its rational grid – affected themselves and the city’s residents. They paid attention to the “ambiances” of places, their accompanying feelings and moods, and the concentration of ambiances in different parts of the city (unités d’ambiance). Positive ambiences would be frequented, negative ones critiqued.

The Situationists encountered their city through what they called dérives (as in “to drift”), which propelled them through the cityscape without a specific goal. More than a privileged flâneurie or a Surrealist introspective painting, the dérive sought to flout or change utilitarian, capitalistic patterns with the very act of walking itself, which resisted the common idiom of the time: Métro, boulot, métro, dodo. Subway, work, subway, sleep. Sound familiar?

Feeling boxed in by the orientation of modern life, with all its time schedules and street signs, commercialism and social alienation, the Situationists sought connection to each other and the city by moving through the city in a disoriented way. (Truthfully, their dérives were sometimes heightened by alcohol or hallucinogens, though I’d advocate, of course, a more lucid resistance to Métro, boulot, métro, dodo.)

They might gather at one place then wander off in different directions to map the psychogeography of their individual routes, returning later to the gathering space to create a new map of the city that highlighted the various ambiances. They might walk from point A to point B, drifting through alleys and into and out of abandoned buildings or through places run-down or of ill-repute instead of sticking to the sidewalks of major streets.

Robert MacFarlane, in his Psychogeography: A Beginner’s Guide, explains this oft-cited dérive: they might unfold a map of Paris, place a glass somewhere on the map, trace its edge, and attempt to walk the circle as closely as possible. He suggests that walkers “record the experience as you go, in whatever medium you favour: film, photograph, manuscript, tape. Catch the textual run-off of the streets; the graffiti, the branded litter, the snatches of conversation.

Cut for sign. Log the data-stream… Complete the circle, and the record ends.” Such détournments (which literally translates as “diversions,” or, perhaps more accurately, “rerouting”) emphasized the Situationists’ belief in the potential of play and experimentation in interrogating established social orders.

This was their art: their movement through the city in order to recreate the life modernity had created. A fitting contemporary parallel is the Parkour movement (developed by French teenager David Belle in the early 1990s), in which traceurs traverse a cityscape without adhering to the patterned infrastructure and social proprieties that guide modern urban life.

I am not suggesting that Milwaukeeans should start flying over railings and bouncing off walls in order to get to and from work, or to explore their city with their families, or to transgress the law – and I’m definitely not advocating drug-fueled dérives. However, if we begin to embrace walking as more than just a heart-healthy activity or a chance to see the city and more as a revolutionary act of creation, with our feet, then we might be on a novel path of establishing and demanding the Milwaukee we want to experience.

© Photo

Janeen M. Kagel, Nick Hansen, Dominic Inouye, Scott Margelofsky, Royal Brevväxling