Wisconsin’s overuse of jails and prisons has resulted in outsized costs for state residents. By emphasizing high-cost incarceration that has produced questionable results over less expensive alternatives, lawmakers require taxpayers and communities to pick up the bill for the state’s short-sighted priorities.

Part of the cost for Wisconsin’s corrections policies come out of the pockets of taxpayers. Wisconsin state and local governments spend about $1.5 billion on corrections each year, significantly more than the national average given the size of our state. The high cost of Wisconsin’s correction policies have made it more difficult for the state to make investments that would do more to increase economic opportunities for residents, such as improving our public schools, making sure that students at the University of Wisconsin can graduate on time, or maintaining local roads.

The other part of the cost is paid by communities, particularly communities of color. Wisconsin incarcerates a higher share of African-American men than any other state, damaging families and individuals and keeping them from reaching their full potential. The consequences of high rates of incarceration harm the economic stability of families and weaken the state’s economy.

Wisconsin should take action to reduce corrections costs by implementing strategies proven to reduce the costs to taxpayers and communities. In fact, Wisconsin has already taken some steps to bring down costs, but so far those steps have been small. Wisconsin should invest more in alternatives to incarceration, reduce the number of prison admissions that do not involve new crimes, and expand employment opportunities for people leaving incarceration. Doing so will save taxpayer dollars, increase the likelihood that people leaving incarceration can be economically self‑sufficient, and make sure that everyone has a chance to contribute to their community.

The Opportunity Cost of Corrections Spending

Wisconsin’s corrections costs have climbed in recent decades, reducing the amount of resources available to make investments in Wisconsin’s families, schools, and communities. Reducing Wisconsin’s corrections costs would increase the amount of resources available to dedicate to making the state a more attractive place to raise a family, work, and do business.

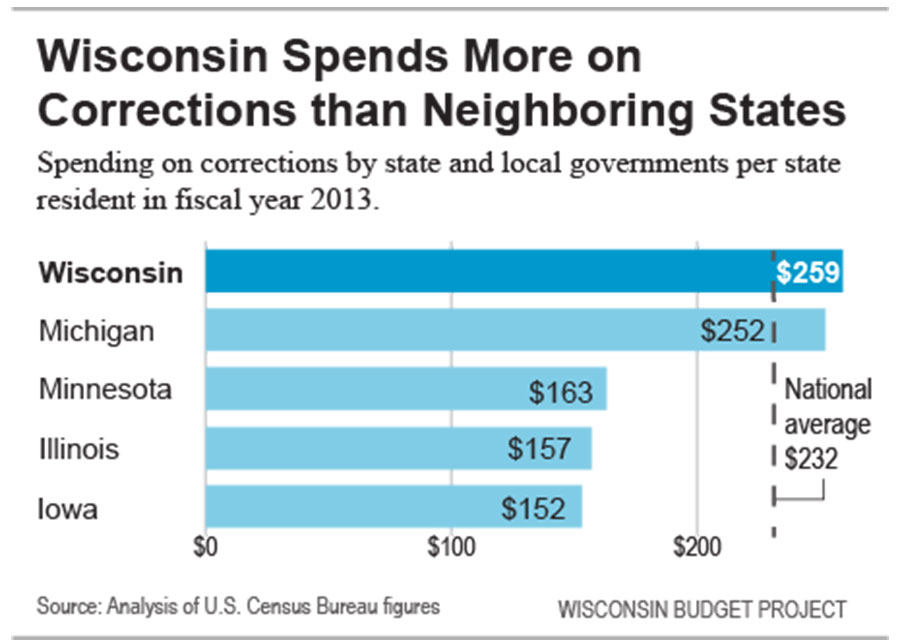

Wisconsin’s corrections costs are out of line with those in other states. Wisconsin state and local governments spent $1.5 billion on corrections in 2013. That’s over than a tenth more — 12% — on corrections per state resident than the national average, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures from 2013, or $27 more per state resident. Nationally, only 11 states spend more on corrections per state resident than Wisconsin.

(Making useful comparisons of spending levels among states requires combining both state and local government spending, since various duties are performed at different levels of government in different states.)

Wisconsin state and local governments spend more on corrections than governments in the neighboring states of Michigan, Illinois, Minnesota, and Iowa. Wisconsin spends 3% (or $7) more per state resident on corrections than Michigan, the neighboring state with the highest corrections costs, and 70% (or $107) more on corrections per state resident than Iowa.

If Wisconsin spent the same amount as Iowa on corrections per state resident, our state and local governments would spend $613 million less on corrections each year.

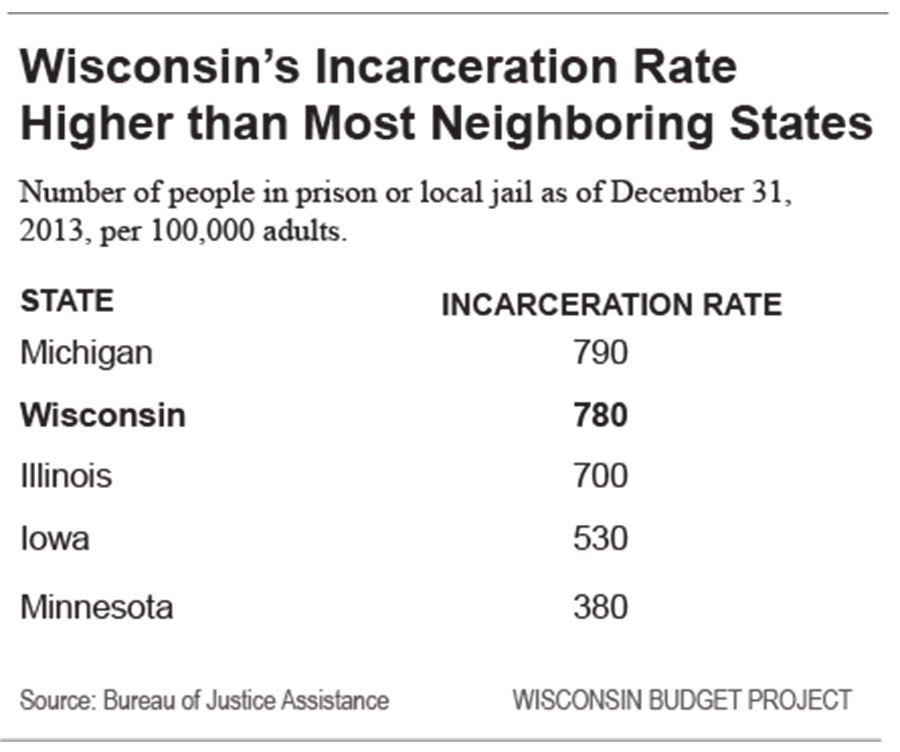

One of the reasons Wisconsin spends more per state resident than our neighboring states is that Wisconsin incarcerates a larger share of our population than most of our neighboring states. The cost of incarcerating an inmate in a Wisconsin medium security prison for one year is $29,900 according to 2014 information from the Wisconsin Department of Corrections.

Wisconsin has more people in prison or jail for our state size than Illinois, Iowa, or Minnesota. Among neighboring states, only Michigan has a higher incarceration rate, and Michigan’s rate is only slightly higher than Wisconsin’s. Wisconsin incarcerates more than twice as many people for our population size than Minnesota.

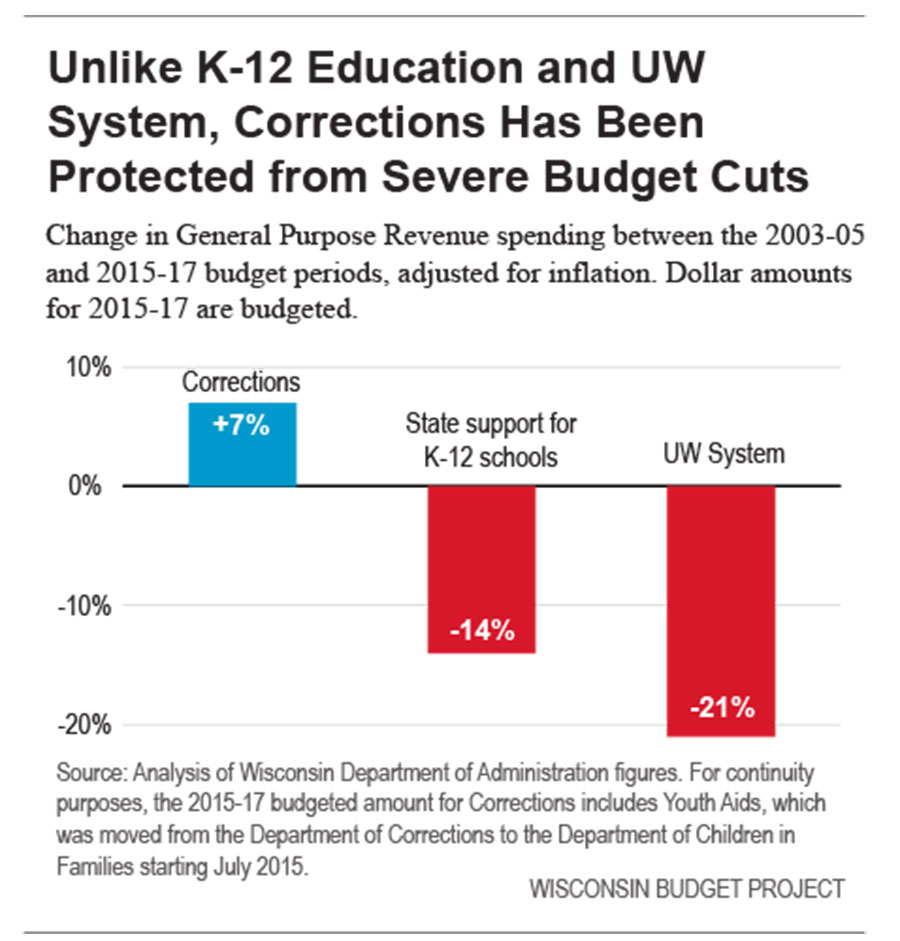

High incarceration rates and the resulting high corrections costs have meant there are fewer resources to invest in Wisconsin’s schools, communities, and health care system. The amount of money that Wisconsin spends on corrections has grown in recent years, even as the state has made deep cuts to public support for K-12 schools and higher education.

Wisconsin state government will spend 7% more in General Purpose Revenue (GPR) on corrections in the 2015-17 state budget than it did in the 2003-05 budget, after controlling for the effects of inflation. In contrast, the state is budgeted to spend 14% less on K-12 public schools in the 2015-17 budget than it did in the 2003-05 budget, and 21% less on the University of Wisconsin System.

As a result of continued growth in the corrections budget and cuts to the UW System, Wisconsin state government now spends more in General Purpose Revenue on corrections than it does on the University of Wisconsin.

The Cost to Communities and its affect on people of color

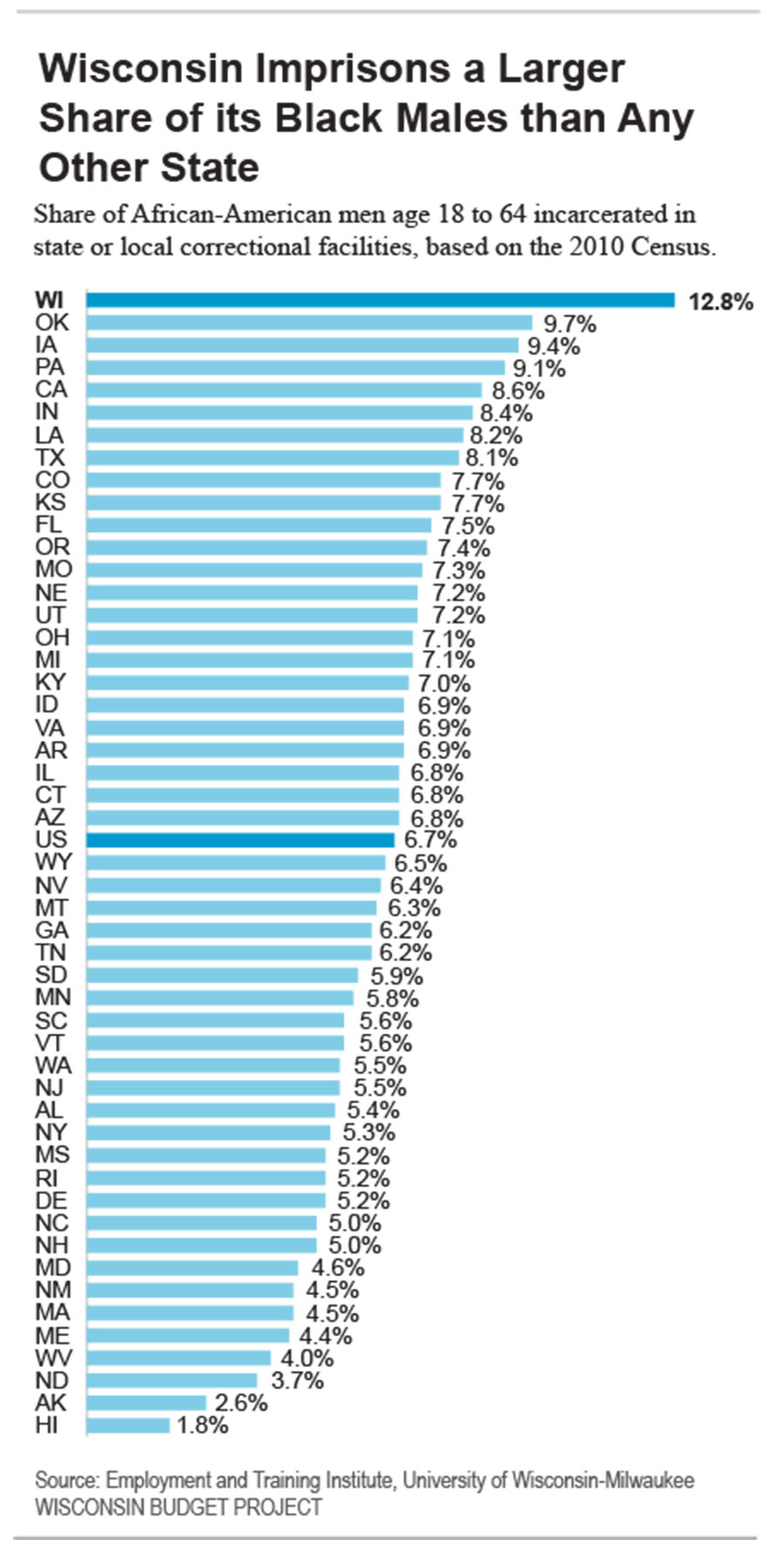

Wisconsin’s overreliance on incarceration hurts families and communities, and has harmed African‑American communities in particular. Wisconsin locks up a greater share of African‑American men than any other state, making it difficult for those individuals to get jobs after they are released, support their families, and make contributions to the state’s economy.

One out of every eight African‑American men in Wisconsin are behind bars, and Wisconsin locks up African‑American men of working age at nearly twice the average rate nationally. Wisconsin also locks up a bigger share of Native American men than any other state.1

The 12.8% of African‑American men who are incarcerated in Wisconsin far exceeds the share locked up in any other state. For comparison, Wisconsin incarcerates more than twice as many African‑American men than Minnesota does given the relative population sizes, more than 80% more African‑American men than Michigan or Illinois, and 27% more than Iowa.

Individuals who have been incarcerated often have a hard time finding work, and the high rate of African‑American incarceration in Wisconsin has contributed to a high unemployment rate among African‑Americans. One out of five African‑Americans in Wisconsin were out work and looking for a job in 2014, and the unemployment rate among African‑Americans in Wisconsin was nearly five times as high as it was among whites.2

Wisconsin’s incarceration of African‑Americans is far out of line with rates in other states, and communities are dealing with the effects of having people who were formerly incarcerated struggle to find work.

Steps for how to Reduce Corrections Costs

The good news is that there are concrete steps Wisconsin can take to bring down the high monetary and community cost of its corrections policies.

By taking steps to cut the cost of corrections, Wisconsin would be following in the steps of other states like Kansas, South Carolina, and Texas that have considered alternative approaches to corrections. Texas, in particular, experienced significant cost savings from a series of reforms aimed at putting fewer people in prison:

From 2007 to 2011, Texas enacted laws that created drug treatment programs, offered non-prison sanctions for technical parole violations and expanded parole and probation eligibility….[Through fiscal year 2013], these reforms saved the state an estimated $2 billion in prison construction costs and reduced its projected prison population by over 11,000 people. After 2007, as in Kansas, Texas’ crime rate fell to the lowest level since 1973.3

By investing more in keeping people out of prison and making sure individuals can get a job after they are released, Wisconsin can reduce taxpayer costs and increase the chance that people leaving incarceration can contribute to their communities. Some of these approaches are already being pursued on a trial basis, but are only available to a limited number of people. Expansions of the programs would increase the number of people benefitting and the dollars saved.

Strategy #1: Expand an approach with a proven track record of keeping people out of prison

The state has the potential to save a significant amount of public resources by making additional investments in an approach that keeps offenders who commit minor crimes out of prison or jail, instead treating their mental health and addiction problems.

Wisconsin’s Treatment Alternative and Diversions (TAD) program awards state grants to counties for programs that keep people with addiction and mental health issues out of jail and prison, and in effective treatment programs. Each dollar the state invests in the TAD program saves $1.96 in public costs by reducing incarceration and lowering the risk that offenders will commit new crimes.4

Wisconsin’s TAD program has grown in recent years and has served as a model for other states seeking to reduce incarceration and corrections costs, but only about half of Wisconsin counties get grants from the state to support these alternatives. Currently, the state spends about $4 million on TAD per year, or about 0.03% of the total corrections budget. Increasing that amount would save money and keep people out of jail.

Strategy #2: Reduce the number of prison admissions that do not involve new convictions

Many people entering Wisconsin prisons are not sent there as a result of being convicted of a new crime. Rather, they are sent to prison because they violated a condition of their probation or parole. In these cases, probation or parole is said to be “revoked.” Examples of grounds for revocation include “simple acts done without explicit prior permission from probation and parole agents, such as accepting a job offer, unauthorized use of a cell phone or a computer, borrowing money, or stepping over a county line,” according to WISDOM, a faith-based organization that works to reduce mass incarceration.5

Revocations without a new conviction made up more than 4 out of every 10 of admissions to Wisconsin prisons in 2014. The price tag for incarcerating people for rules violations adds up fast: Revocations for technical reasons that don’t stem from new convictions cost the state in the neighborhood of $140 million per year, according to an approximation from WISDOM.

The state has had some success in reducing the number of prison admissions that do not involve new convictions, but the number can be reduced further. WISDOM has proposed that Wisconsin adopt a policy similar to Minnesota where offenders who violate technical conditions of supervision may participate in a sanctions conference in lieu of a formal revocation proceeding, a move that could reduce the number of people sent to prison for rules violations. Keeping people on probation out of prison would also have the advantage of allowing offenders to continue working, instead of losing their jobs when they return to prison.

Strategy #3: Reduce recidivism by removing barriers to getting a job

Getting a job helps people leaving prison or jail provide for their families and contribute to their communities. But several obstacles can stand between people leaving incarceration and obtaining regular employment, and many employers are reluctant to hire someone with a criminal record.

Wisconsin state and local governments can take two steps to remove barriers to employment, and increase the likelihood that people can both stay out of poverty and avoid committing new crimes:

Help people with limited work skills enter the job market, by expanding the state’s transitional job program

The transitional job program provides public and private employers with a temporary subsidy if they hire individuals with low incomes who meet certain criteria, thereby helping the individuals develop work-related skills they need to find employment on their own after the subsidy ends.

Helping individuals who are leaving incarceration obtain and keep jobs reduces costs to taxpayers and communities. A study of a transitional job program in New York specifically targeted at people leaving incarceration found that every $1 dollar invested saved taxpayers $2.13 from reduced criminal justice expenditures, reduced victimization costs, and increased employment.

Wisconsin’s current transitional job program is small, enrolling less than 600 workers last year, and is focused only on workers in the City of Milwaukee. Expanding the program would help give individuals leaving incarceration a route towards economic self-sufficiency, while reducing public costs related to incarceration and the criminal justice system. Lawmakers have already taken a small step in this direction, by adding $3 million in the next two years to expand the transitional job program, but more can be done.

Give job-seekers with past involvement in the criminal justice system a chance to be evaluated on their skills and experience

Getting a job can help individuals leaving incarceration avoid future involvement in the criminal justice system. But some employers ask about previous convictions early in the application process, and immediately disqualify anyone who has been previously incarcerated. That practice makes it harder for people leaving incarceration to become contributing members of their community.

By moving the question about criminal history to the end of the application process, employers can evaluate candidates on their merits, and job seekers can get the opportunity to respond to questions about their history. At that point, employers can decide whether or not to offer the job to the applicant. Moving questions about criminal history from the start to the end of the job application process is sometimes called “Ban the Box,” a reference to the yes/no checkbox asking about convictions on initial applications.

Wisconsin can take steps to improve employment opportunities for people leaving incarceration by requiring employers to postpone asking about past convictions until later in the application process. By doing so, Wisconsin would be following in the footsteps of Illinois and Minnesota, which have already banned the box for all employers. Some local governments in Wisconsin, including Milwaukee County, Madison, and Appleton have said they will ban the box from their own application processes for many jobs. A 2015 Republican proposal to make changes for the state’s civil service system included a provision that would the ban box from state job applications, an indication that banning the box is an issue that can garner support from both Democrats and Republicans.

- Wisconsin’s Mass Incarceration of African American Males: Workforce Challenges for 2013,” Employment and Training Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013.

- “The State of Working Wisconsin 2015,” COWS, 2015.

- “Improving Budget Analysis of State Criminal Justice Reforms: A Strategy for Better Outcomes and Saving Money,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and American Civil Liberties Union, January 2012. Texas’ prison population later began to grow again, possibly signaling a need for further reform.

- “Treatment Alternatives and Diversion (TAD) Program,” University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, 2014.

- “11×15 Blueprint for Ending Mass Incarceration in Wisconsin,” WISDOM, 2014.

- Wealth gap leaves Milwaukee families of color financially vulnerable

- Income inequality adds to growing divide in Milwaukee

- Rising tide of poverty adds to challenges in Milwaukee Schools

- State Corrections policies and the high cost for Milwaukee

- Mortgage lending structures reinforce segregated poverty