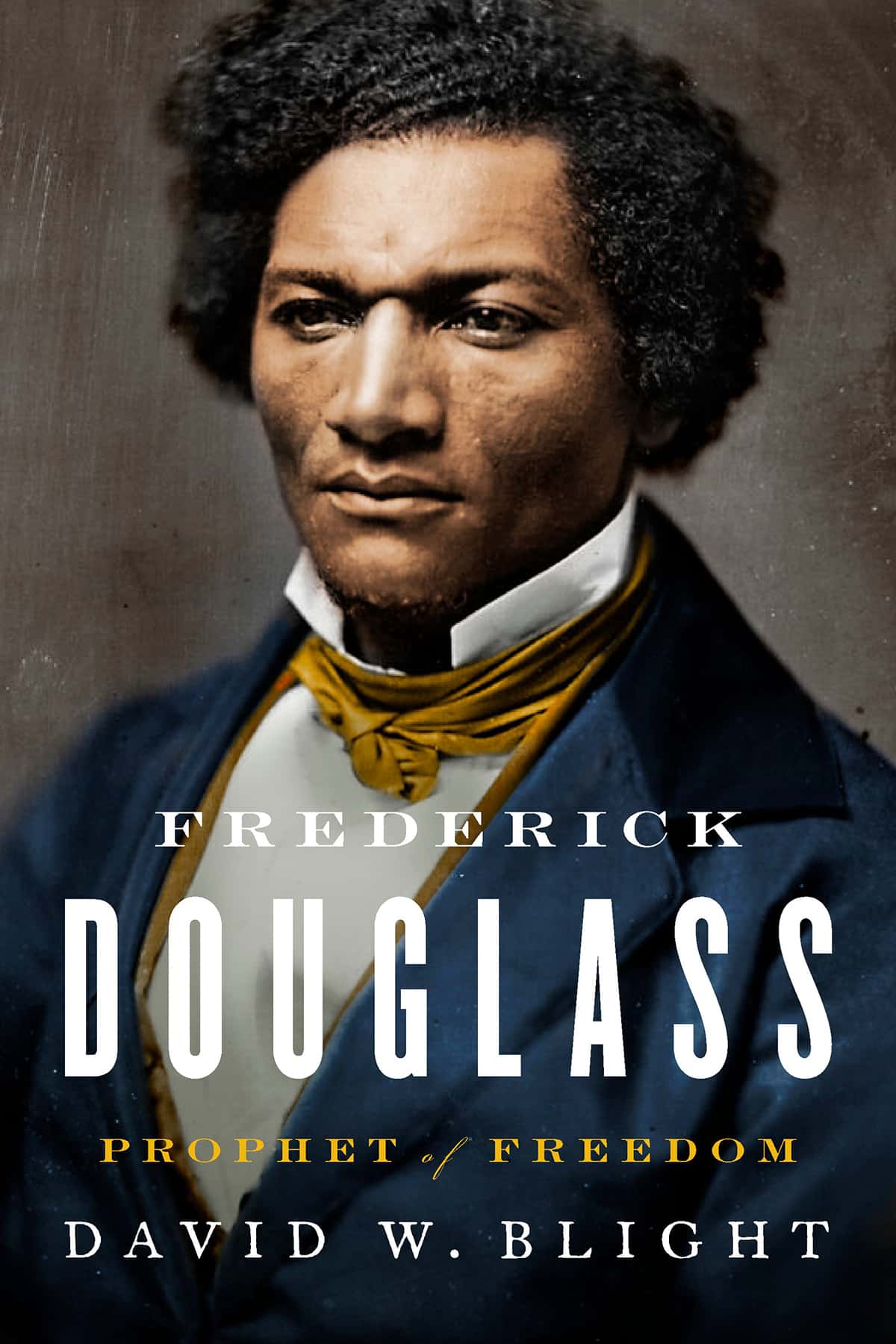

David Blight has written a must-read life of the escaped slave who held America “to the lightning scorn of moral indignation.”

If Frederick Douglass had been born white in 19th-century America, he would be remembered as a self-made man in the style of Thomas Edison. In 20th-century America, postwar, he could have been a counselor to presidents, like James A Baker, or perhaps a media personality, even Walter Cronkite.

But he was born a slave, in Maryland in 1818, and he escaped to freedom and a life of voice and pen, thundering against slavery and for justice and the rights of African Americans and women – while becoming all those other things as well.

His second wife, Helen, wrote of “the shining angel of truth by whose side I believe he was born, and by his side he unflinchingly walked through his life”. Indeed, Douglass seemed protected. He was taught to read – then a crime – by a white woman, Sophia Auld, in the family that enslaved him.

He worked in Baltimore, was converted as a teenager to a strong personal faith, and taught himself oratory from sermons and books. In 1838 he escaped north, making a new life and taking a new surname, adapted from Sir Walter Scott.

As David Blight writes, “Douglass’ great gift … is that he found ways to convert the scars Covey [a slave master] left on his body into words that might change the world. His travail under Covey’s yoke became Douglass’ crucifixion and resurrection.”

Once he began telling his story in public, Douglass brought the brutal inhumanity of slavery to northern audiences and launched his true life’s work. Three autobiographies and countless pamphlets and editorials show a language both lyrical and beautiful. “We have opened our papers,” he wrote, “new and damp from the press.”

Early efforts included a visit to Britain in which Douglass experienced the exhilaration of avoiding race prejudice for the first time. He founded the North Star newspaper, attacking slavery in the south and racism in the north, and supported women’s suffrage at Seneca Falls in 1848. The anti-slavery movement was racked by conflict but he gave as good as he got.

During the civil war, Blight writes, Douglass “equate[d] treason with slaveholding” and advocated using the war to end slavery, its cause, deploying black troops to do so. He met Lincoln several times, notably at the White House in 1864, where he was “treated as a man.”

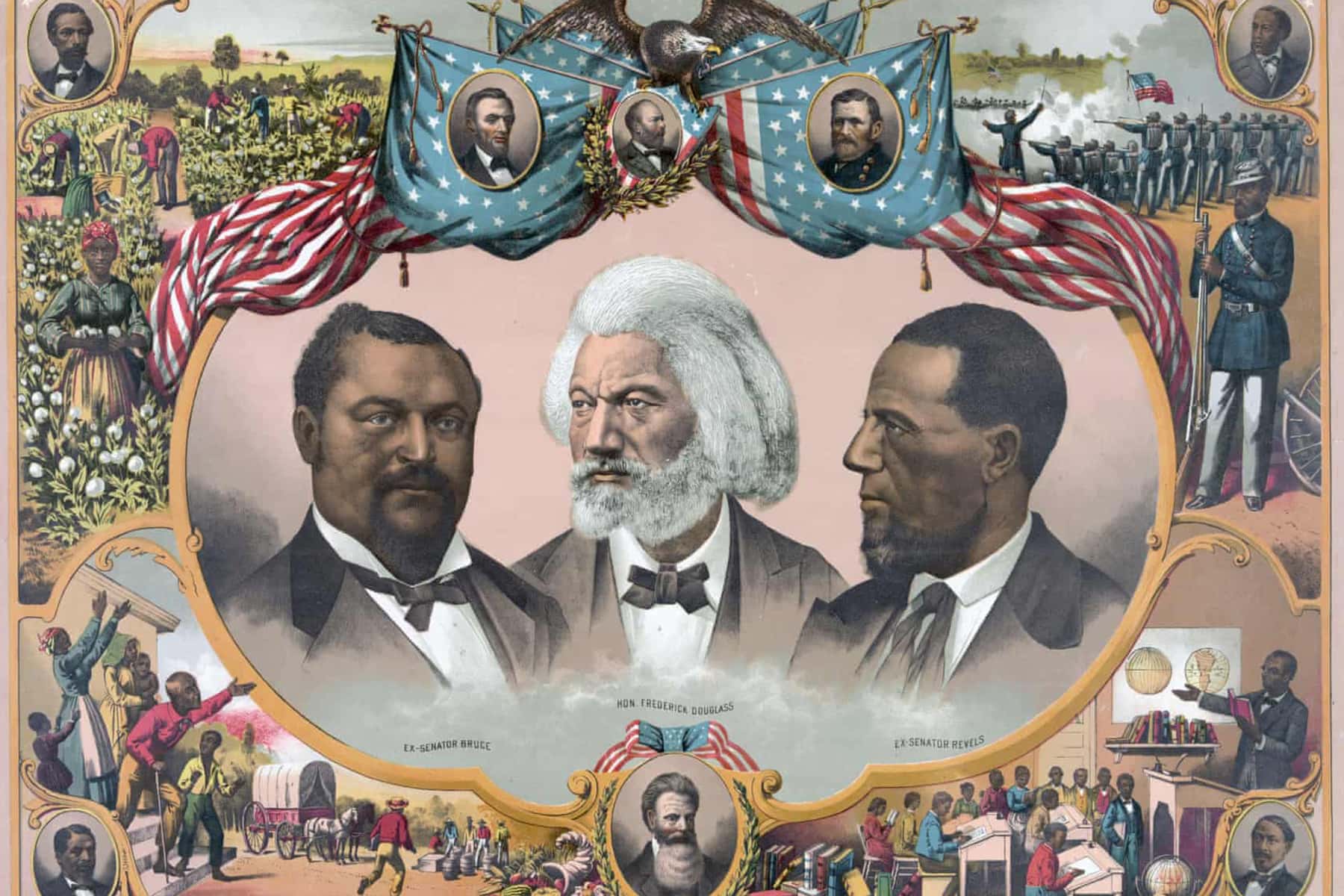

After the war, Douglas fought for votes for African Americans. “If the old abolitionist needed a new occupation,” Blight writes, “he surely had one now – the frightening black man with brains who had penetrated the racist psyches of powerful people with words and his physical presence.”

Moving to Washington, he became active in Republican politics. He perceptively described the end of Reconstruction as “peace among the whites” and promoted “elbow room and enlarged opportunities” for black citizens along with strong federal enforcement of their rights.

Selected as U.S. marshal for the District of Columbia by President Rutherford Hayes, he even met an ageing Thomas Auld, Sophia’s brother-in-law, as a way “to declare his equality, and in a way to practice a self-renewing forgiveness.” Both shed tears. Douglass, one hopes, achieved a measure of internal peace.

Blight’s book is – thankfully – not a psychobiography. But it offers penetrating insights into the effect slavery had on Douglass’s personality.

“Douglass engaged in a lifelong autobiographical quest for a coherent story of ascendance and familial identity,” Blight writes, and “for the healing of his own wounds.” Douglass himself thundered that slavery “converted the mother that bore me into a myth, it shrouded my father in mystery, and left me without an intelligible beginning in the world.” He yearned for “a bright gleam of a mother’s love.”

This is a monumental book, a definitive biography, rich with the biblical cadences that filled Douglass’ life and imagination. Slavery, redemption, vengeance, justice: these were Douglass’ themes, and like Jeremiah he would be a prophet to an often recalcitrant people. The lecture halls expected no less yet Douglass gave them more, probing new depths of social and political analysis, constantly imploring greater exertion for the causes of emancipation and full equality, unafraid to make his hearers deeply uncomfortable.

“I will hold up America to the lightning scorn of moral indignation,” he wrote in 1847. That is what prophets do – real prophets rather than those who speak peace where there is none.

And of that popular conceit of today, Douglass as Republican? The truth is, Douglass was a partisan because only (and only some) Republicans showed any interest in protecting African-American rights and votes. His radicalism was above party.

In response to criticism of Douglass’ acceptance of political office, Blight notes that “some freedom fighters wear starched shirts, cultivate their appearance, and battle evil with words.” One might think the modern Republican party could encourage “Douglass Clubs” among recent immigrants – and then expect them to hold their party’s feet to the fire. It might work.

After all, recent presidential tweets could never have been more effectively skewered than by the editor of Frederick Douglass’ Paper. Blight records his response to the blusterings of Abraham Lincoln’s impeached successor: “‘What shall be said of Andrew Johnson?’ better ‘leave Mr. Johnson speak for himself as being the most damaging thing he can do.’”

This was a turbulent rather than tranquil life. What WEB DuBois called the “problem of the color line” has never disappeared. And so the fundamental tension in Douglass’ thought and words endures. As he wrote, “if American conscience were only half-alive,” injustice would cease and “based upon the eternal principles of truth, justice, and humanity … your Republic will stand and flourish forever.”

At his bicentennial, Frederick Douglass, the escaped slave who became a colossus, still stands witness in the conscience of the American people.

John S. Gardner

Originally published on The Guardian as Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom review: a monumental biography

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.